|

When General Joseph Stilwell, the first commander of the China-Burma-India Theatre, was being moved to the hospital from his home during his terminal illness, he is reported to have said to his wife, "I wish I were going to the 20th General."

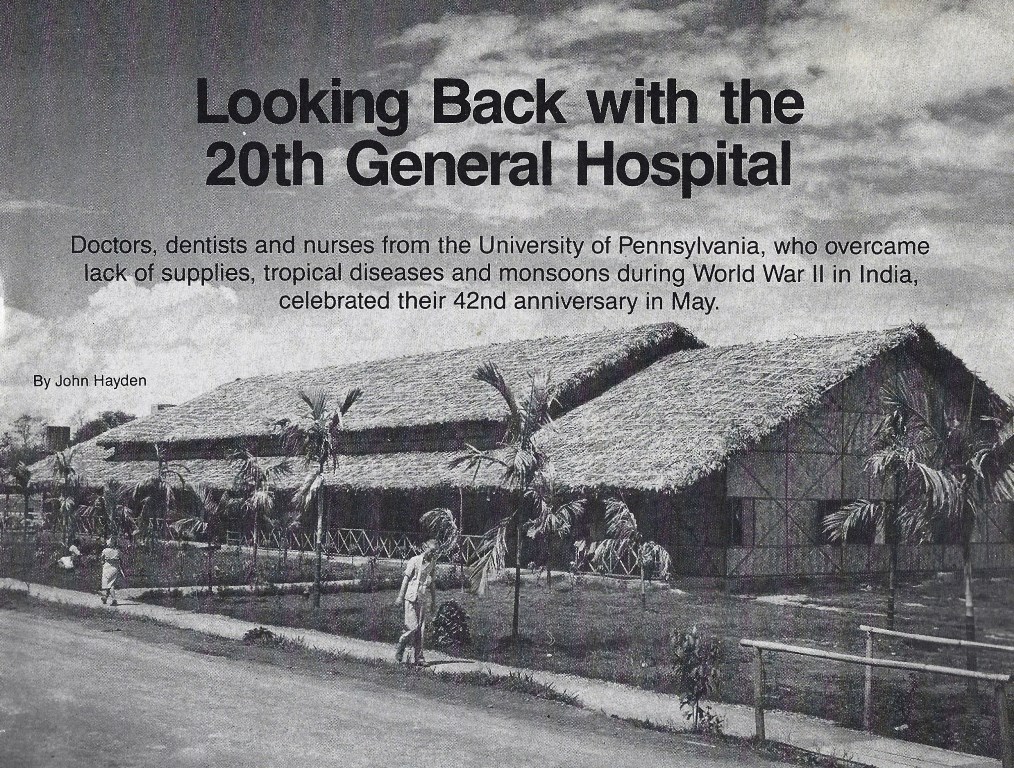

He was no doubt thinking of the first-rate 2,500-bed hospital the 20th General had finally built, with 148 buildings covering 1½ square miles. When staff members of the 20th General first arrived in Margherita, Assam, near Ledo, in the northeast corner of India near the Burma border on March 22, 1943, they were astonished to see only three small buildings with concrete floors, tin roofs and open fronts, as well as a group of bamboo huts, called bashas, with dirt floors and light showing through their thatched roofs.

"Since the monsoon had begun the day before our arrival, the first view of the hospital was something never to be forgotten," said Dr. Francis Wood, who was head of the medical service. "We splashed out of the trucks into nearly six inches of soft slippery mud. It was a raw day with leaden clouds and a driving rain. The hospital was being run by the 98th Station Hospital staff. Around a large flooded polo field that had been used before the war by the British tea planters were two slightly elevated clearings in the jungle. On higher ground to the north were a group of bashas where the American patients and our nurses were quartered. On the south was another group where the officers and detachment were billeted. To the southeast was another large collection of bashas. This was the Chinese section of the hospital."

Dr. Wood said that in the beginning the bashas were 20 by 80 feet with a 20 foot extension for latrines. To improve sanitation they later built latrines away from the living quarters.

"Conditions were very primitive during those early months," the late Dr. John Paul North of Dallas wrote in an article for Surgery in 1964. He had been chief of the surgical service after Dr. Ravdin had taken command of the unit. "There was no mosquito netting and the walls of the bashas, made of coarse woven matting, offered no protection from either the weather of the malarial mosquitoes. We had to string up tarpaulin over our beds to keep the rain out. But these structures had to do for months before they could be replaced." They put electric bulbs in their foot lockers to keep the mildew from growing.

"Patients got wet," Dr. Wood said. "But it didn't seem to do them any harm. One of the incredible sights that first summer was a bamboo basha that blew down in a storm. It was full of Chinese patients and it settled first at the rear and spewed Chinese soldiers from the front so fast that no one was hurt."

Dr. Wood remembered that housekeeping in their quarters was done by Indian bearers, who were extremely helpful, though not well versed in sanitation. "We found them scouring our glasses and dishes with amoebic earth and washing them in bacillary water," he said. "They swept our rooms, washed socks and underclothes, shined shoes and belt buckles, made beds and put mosquito nets up and took them down - and smoked our cigarettes."

Before the unit was able to set up its own laundry, the Indians also washed sheets in a stream. Instead of coming out white, they were a brown, dirty-looking color. According to Lieutenant Cordelia Shute. "That was one of the things that one had to become accustomed to - that you had no endless supply of clean linens. And with the patients perspiring, it was not too great. Eventually, we did have a good supply. But not at first."

When they first arrived the nurses had to wade through mud, wearing low shoes until the officers supplied them with their own army boots or until they could get proper foot wear, Dr. Wood said. At the staging area near Riverside, California, overseas tropical equipment had been issued to the nurses and then for some unknown reason recalled. They left the country wearing blue woolen uniforms and black oxfords, while heading for duty in a steaming jungle where the annual rainfall is 140 inches.

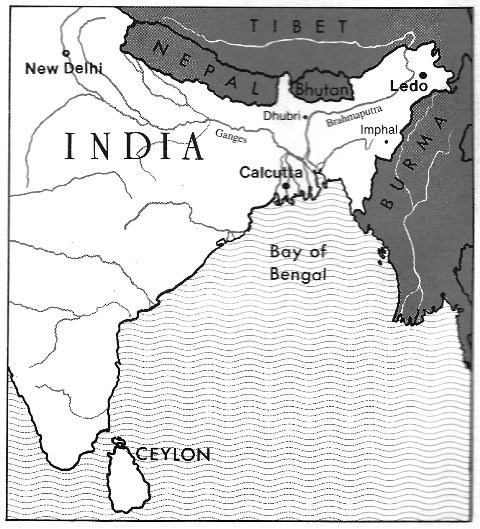

The mission of the 20th General, according to Dr. North, was to provide care for troops of the Services of Supply engaged in constructing a road from Ledo, Assam, into North Burma to restore land communications with China, which had been cut when the Japanese knocked out the Burma Road. The unit also cared for Chinese soldiers who were serving as a screen when the road was pushed forward. They were admitted to a separate section of the hospital because they had their own special rations and needs.

|

Dr. Wood recalled that they coasted along for the first month rather peacefully. Slowly increasing the number of patients in the hospital. Then suddenly, about the middle of June the first tidal wave of malaria patients hit.

"From that moment until the first of November, every officer and nurse on the medical service worked to the limit of endurance. One of the interesting things about working that hard in the monsoon was that we would become very irritable. At home I might get angry about twice a year. During that first summer, it happened about three times a week. When the autumn came, I looked back on my behavior and realized that I had been moderately psychotic. The second year, we expected this and were better able to make allowances for ourselves and others."

Despite the trials and labors of the first year and the irritations to which everyone was subjected during the monsoon, nothing even remotely resembling a major schism or important internal quarrel occurred, Dr. Wood reported. "As time went on, constant close contact, inevitable in an organization established in a recreational desert, caused us to become acutely aware of each other's faults and frailties. At first, these observations probably brought annoyance and disillusionment. However, as time went on and as we worked shoulder to shoulder in the heat and mud, the capabilities of individuals tended to overshadow defects. We began to like each other despite the faults. We had to. This is probably what has been called 'the virtue of tolerance.' and it was beneficial."

Dr. Wood recalled that the case load the first summer was almost all medical, with either malaria or dysentery. They rolled in by the truck load. The unit was forced to open new wards one after the other.

One afternoon he was asked to open Ward K22 in preparation for a possible influx. He got there with medical supplies at 2:00 and at 2:15, while they were still unscrambling piles of equipment, the R&E Officer walked in and announced that in 15 minutes they would have 40 very sick patients.

"While the patients were streaming in, nurses and corpsmen would make up the beds, hang mosquito netting and arrange ward books, records, supplies and equipment. At the same time, officers would be examining patients. The surgeons pitched in to help in these recurring emergencies. The chiefs of services worked with the ward officers and were often to be found doing histories and physical examinations late into the night when new wards were opened," Dr. Wood said.

Taking care of the Chinese patients presented special problems because none of the staff spoke Chinese and interpreters were scarce.

"Yet we all soon learned a few Chinese words and with some pantomime became able to take histories faster than we could with interpreters. We soon got to the point that we could single-handedly, without calling for help, examine, diagnose and treat a whole ward full of Chinese admissions, about forty in two hours, and be pretty accurate about it, although the records were a bit scanty," Dr. Wood pointed out.

During the summer of 1944, they began to get Chinese patients with obscure abdominal pains. After much study we learned that they were suffering from hookworm invasion. In one instance, Dr. Wood recalled that a Chinese sergeant came in with abdominal pains that at first seemed to be appendicitis. "So I asked Julian Johnson to explore it. I went into O.R. after Julian has opened him up. As I came in he said, 'Fran, you got a butterfly net? Come look at this.' All over the fellow's peritoneum were little curled-up worms. There must have been 150 of them. We cut out several and I sent them to Washington to see if we could find out what they were. I asked everyone I saw if he could identify them. Finally, a fellow from Harvard said they were Armillifer Oreintalis and that they came from cold blooded animals. It turned out that the patient had killed a huge snake up in the jungle. He had given the snake to his men but he had eaten the liver."

Another of the problems with the Chinese was in getting them to give blood. When the Chinese battle casualty admissions became heavy and much blood was needed, a team of one officer and three nurses would drive up the Ledo Road twice a week in a weapons carrier to one or another of the Chinese camps, take blood in rather unusual surroundings and bring it back. This was only possible because of the leadership of certain key Chinese officers, especially General Sun.

Some of the Chines patients had advanced tuberculosis. "It was practically impossible to teach them to stay in isolation and to refrain from expectorating on the ground near other patients. If we weren't careful, we would find them with other patients playing cards and coughing in their faces," Dr. Wood said.

|

In 1943, from June to October, the medical service had 7,236 admissions for malaria alone, 705 for bacillary or amebic dysentery. Almost half of the malaria cases were of the falciparum variety, many of the cerebral type. These cerebral malaria patients, usually Chinese, might lapse into coma an hour after walking into the ward and without intensive therapy might be dead within 24 hours. Colonel Thomas Fitz-Hugh reported a mortality rate of 33 percent in the Chinese patients compared to 5 percent in Americans. They saw all variations of cerebral manifestations from mild dizziness or slight drowsiness to severe headache, coma and convulsions.

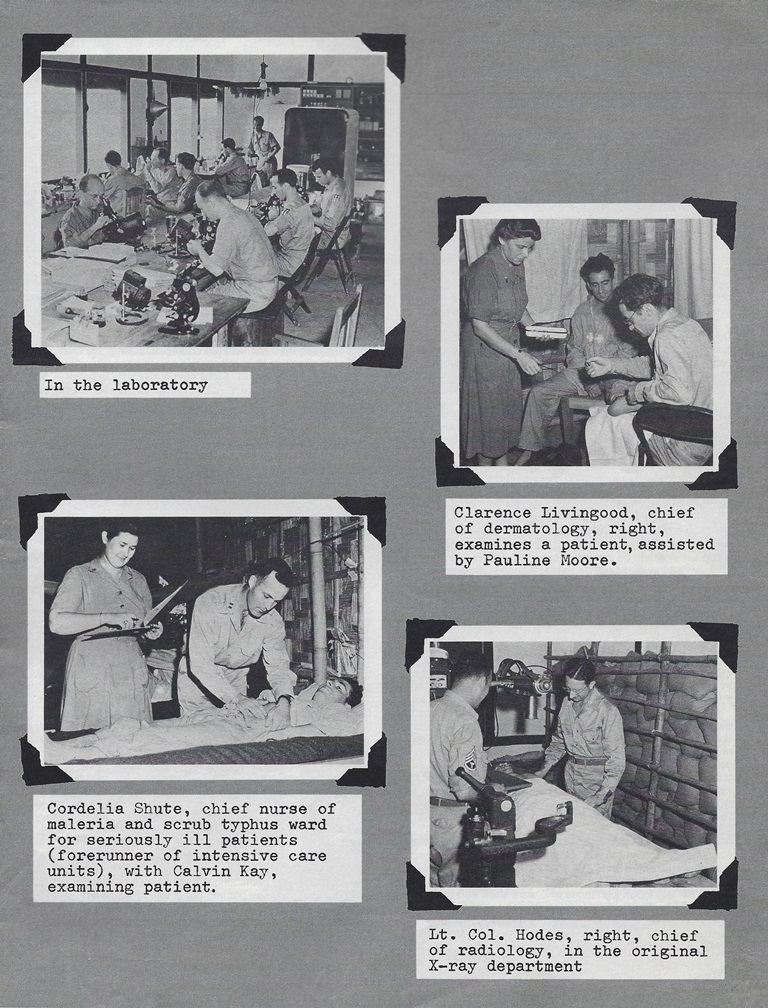

By the middle of November malaria dropped off. "We began to lick our wounds. That winter Major Calvin Kay carried out a study to analyze the incidence of new infections, reinfections and relapses at different times of the year for the two main types of malaria, vivax and falciparum," Dr. Wood said.

In this study, Dr. Kay found that of the unclassified infections, further smears showed almost without exception, that falciparum rarely relapsed, that vivax relapsed in about 35 percent of the cases after one attack, and that once vivax had relapsed a second relapse occurred in about 75 percent of the cases.

The 20th General Hospital was formed in 1940 when the Dean of the School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania was asked to organize an Army hospital unit. But the unit did not receive orders to leave Camp Claiborne, Louisiana, until May 15, 1942. It remained there for 7&ffrac12; tedious months before moving on January 5, 1943, to Camp Anza, a staging area near Riverside, California. It finally sailed on the transport Monticello, a converted Italian cruise ship, (Conte Grande), on the morning of January 20, and reached Bombay on March 3 - 42 days out of California, having had only a brief shore leave in Wellington, New Zealand. The last leg of the trip by rail and boat of some 1,500 miles began on March 13. At Dhubri the unit boarded a river boat and for two days steamed up the Bramaputra, one of the longest and widest rivers in the world. At Pandu, they boarded another train which snaked for 36 hours through Assamese jungle to Margherita in the northeasternmost corner of India.

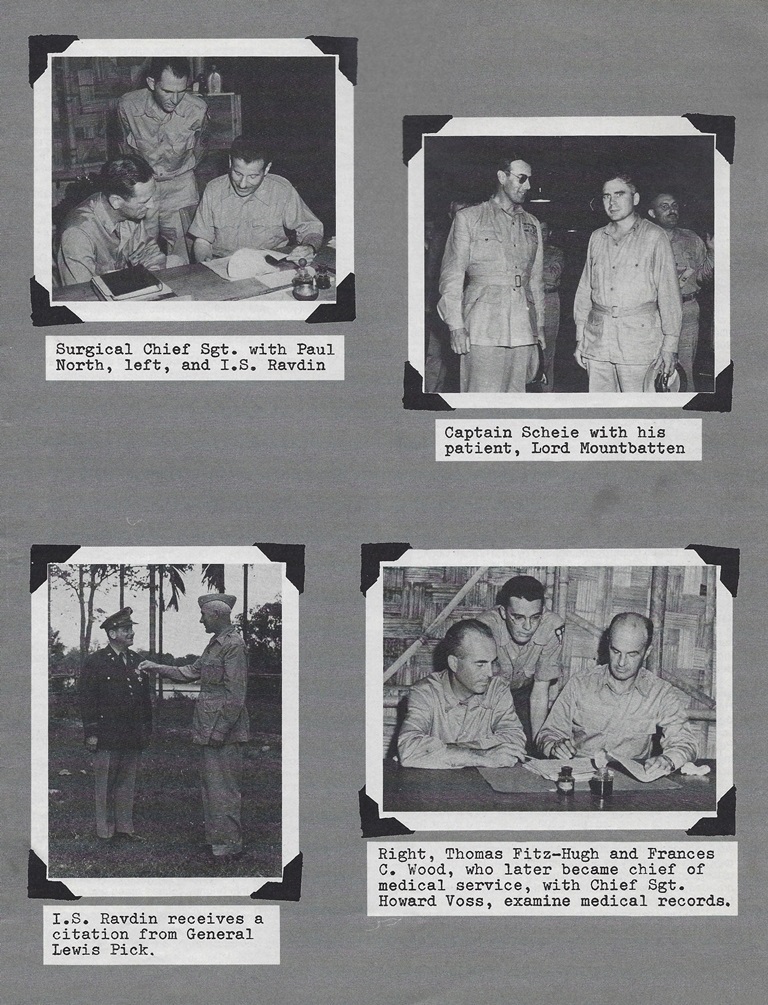

On November 13, 1943, Colonel I. S. Ravdin assumed command of the hospital. Dr. Ravdin foresaw that before many months they would be serving some 2,500 patients and he had to work toward having adequate wards, though everything was difficult to obtain because they were in a theatre of war that had a low priority.

Dr. Wood gave some insight into the way Dr. Ravdin was able to build so quickly. "In the beginning, when we were living in those flimsy bashas, we were a little annoyed to see him erect a couple of substantial wards to care for top-ranking officers. But after they had been cared for and were ready to leave, they were always very appreciative and would ask Rav what they could do for him. He wouldn't hesitate to tell them. This way he got the building done in half the time any of the rest of us could have."

Dr. Ravdin had been an inspiration to everyone during the discouraging months in Louisiana and on the long journey to Southeast Asia, Dr. North pointed out. He always had the welfare of the patients uppermost in his mind, and he was also concerned for the comfort of his personnel. Only after essentials, such as decent quarters and adequate arrangements for bathing were taken care of, did he consider recreational facilities. In his typical way, he first took care of recreation for enlisted men and later for officers. Eventually there was even a covered movie theater.

In spite of the handicaps faced in the beginning, Dr. Ravdin was determined that the 20th General Hospital would become the best hospital in the entire army. His enthusiasm transmitted this goal to everyone who worked with him.

"He was tough with those who were slack with their work or who did not make good with their promises, yet many of all grades in his command still remember him for some act of kindness concerned with their personal problems," Dr. North wrote. "He had the tenacity of a bulldog about securing supplies which were needed and would refuse to be sidetracked along the chain of command, but would go to the top if necessary."

In November 1943, the first scrub typhus patient appeared. Though the staff failed to identify it immediately, it soon became clear that they were seeing a new disease. In December 1943, Major Dickinson S. Pepper studied all the cases then at the 20th General and traveled down the Ledo Road to investigate the focus of infection around Shingbwiyang and concluded that it was a mite-borne disease. Dr. John Sayen said that the vast majority of patients were not even aware of a bite but that the mite ulcer became so distinctive that it could be easily recognized.

One of the major problems of the disease was high fever and the need to control it. Dr. Ravdin knew that air conditioning would help, but none seemed available.

"After the Myitkyina Airstrip had been captured, we played a part in the evacuation of Merrill's Marauders. Though a rugged group, which had been through about as strenuous a campaign as the average soldier could endure, they were absolutely done in with malaria, dysentery, scrub typhus - everything," Dr. Wood said. "They came to our hospital in droves. About a week later Rav got an order saying, 'Send every man who can walk back to duty because the Japanese are counter-attacking.' He went around to check on the patients and saw that they were in no condition to return to duty. So he sent a message to headquarters refusing the order. About a week later he got a message from General Stilwell up in Burma, ordering him to appear. Rav was certain that he was going to be kicked out of this man's army for refusing an order. Instead, he was pleasantly surprised to find that General Stilwell was congratulating him for saving his reputation. "Some little Napoleon in headquarters wanted to get me into trouble when they sent that order down. And you saved me by refusing to obey it. Now what can I do for you? Rav told him that we needed air conditioning for the scrub typhus patients. Stilwell said, 'Requisition it.' 'I've done that every week for the last four weeks.' Rav said. So General Stilwell asked the man in charge of supplies in Delhi to furnish air conditioning for the 20th General Hospital."

He ordered that 50 percent of it be on planes within 24 hours and the rest within a week. These were air conditioners that had been keeping high-ranking officers in Delhi cool. After that the doctors were able to keep these patients cool and were able to bring their temperatures down. The mortality rate dropped to about 1 percent, whereas before it had ranged between 5 and 20 percent.

Not long after this, General Pick called from Ledo to tell Dr. Ravdin that Lord Mountbatten, the Supreme Allied Commander in Southeast Asia, wanted to come down to dedicate the first air conditioned ward in India that very day.

"It just happened that we didn't have any scrub typhus patients at that particular moment. So we hurried around and took patients from the venereal wards and put them in the scrub typhus ward," Dr. Wood said. "We were all ready for him but by six o'clock he hadn't arrived and the fog was setting in. By 10 o'clock Rav decided that he wasn't coming at all, so we took down all the fixings that we had put into this ward to make it look snappy. We sent all the patients back to their own wards. About midnight we heard a plane buzzing our hospital and then General Pick called from Ledo saying, 'Rav, he's going to do it.' 'Going to do what?' 'He's going to dedicate your air conditioned ward in about half an hour."

Dr. Wood said that they got all the patients back out of the venereal ward into the scrub typhus ward. Lord Mountbatten walked in and after dedicating the ward walked around to talk to the men. One sergeant popped out of bed to salute him.

"My dear man," he said, "you're too sick to be out of bed." Then he asked one of the men where he had gotten his typhus.

"Up near Myitkyina," he said.

"You must be very uncomfortable with it."

"Terrible, Sir. It's the worst thing I've ever had."

The next day Dr. Ravdin called this sergeant in.

"Sergeant," he said, "do you know of any reason why I shouldn't court martial you for lying to the Supreme Commander of Southeast Asia?"

The sergeant saw a twinkle in Dr. Ravdin's eye and he said, "Well, General, I saw you were in a little trouble and I thought I would help you out."

|

This ward was also one of those designated as a critical care, or intensive care ward. Lt. Cordelia Shute, assistant to the director of the Clinical Research Center at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania who was assigned to this ward, said that they pulled 12-hour shifts beginning at 7 a.m. or 7 p.m. Because of having more nurses and other appropriate personnel and equipment assigned to this ward, they were able to give special care, which also tended to lower the mortality rate of scrub typhus patients.

As Dr. Larry W. Stephenson pointed out in a paper, "University Affiliation of a Medical Reserve Corps Unit," the intensive care concept, now taken for granted, was thought to have originated in the early 1960s, but it was already in operation in the 20th General Hospital in the early 40s.

The "shock team" under Major Freeman made it possible to save a number of malaria patients who were very ill with medical shock, when the ward officer, deluged by admissions, could not have given them adequate care, Dr. Wood said.

The x-ray staff endured many problems caused by climatic conditions. Dr. Philip Hodes and his staff worked for months with unshielded equipment that had frequent breakdowns of a 24 kw. gasoline generator. The dampness corroded metal surfaces and damp electrical cables arced, cassettes and diaphragms warped. Exposed film was frequently encrusted with mold in storage the film would often arrive close to or even beyond its expiration date, or was a times already fogged. Still, the x-ray department was able to provide every type of special examination requested and in August, 1944, alone examined 1,852 patients, according to Dr. North.

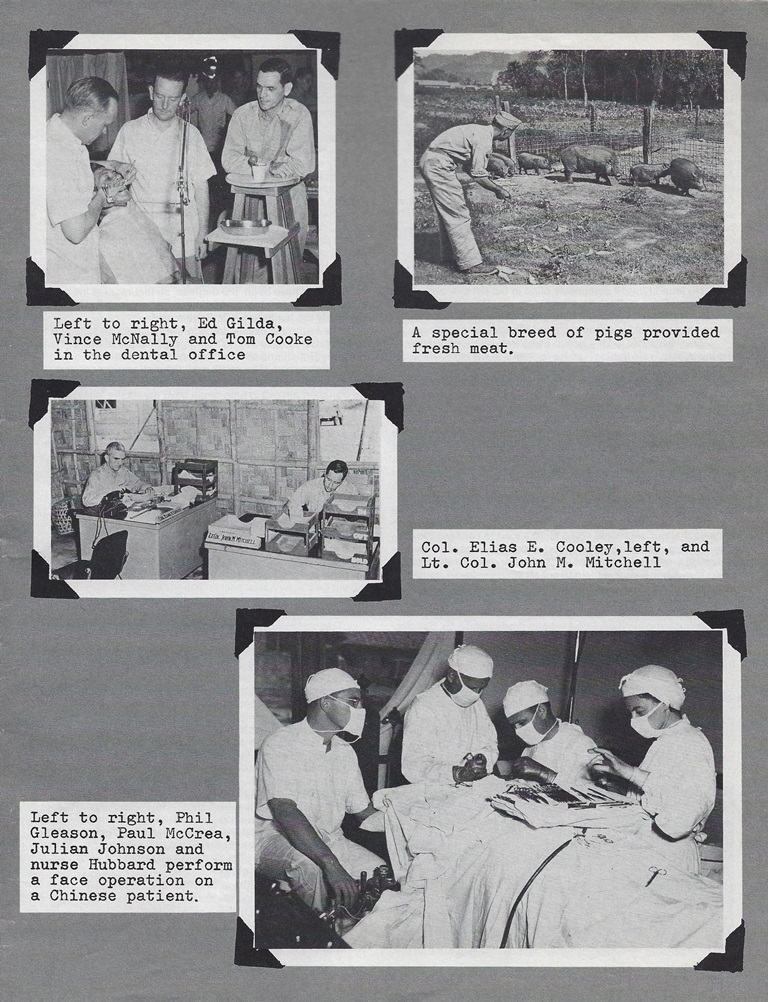

The Dental Department, headed by Dr. Thomas Cook, operated with foot divert dental motors until the engines to operate the dental drills came in October.

"Yet they were able to give dental care in this theatre which was in every way as good as that which could be obtained anywhere," Dr. Wood said.

In addition to treating a large out-patient and in-patient service, Colonel Cook also had to treat 200 battle casualties during the year. The Dental Department met once a month with 50 dental officers from various parts of the theatre.

The Nursing Corps began the year with 105. They lost 38 then added 94. At one time, 26 nurses from the 69th General Hospital helped the unit through a crisis, Dr. Wood said. Moreover the Red Cross workers served as ward nurses during the scrub typhus epidemic of May and June. "First Lieutenant Helen Poulsen did a magnificent piece of work with the Central Dressing Room and, among other activities, prepared intravenous solutions for the entire area," Dr. Wood said.

In the autumn of 1943 the hospital was face with the challenge of completely rebuilding its facilities which were then operating at 40 percent over capacity. During this period the medical service alone had over 1,200 admissions a month from April to October, according to Dr. Wood. All the original buildings were replaced with structures that had concrete floors and metal roofs with leaf overlay for additional insulation. Their double walls of bamboo matting, covered with burlap and mosquito netting, provided ventilation and at the same time kept mosquitoes out. Everything was also screened.

"But you can imagine the difficulties of moving in and out of old and new wards while such a rush was on," Dr. Wood said.

After they had been there for several months, Dr. Ravdin saw that a vegetable garden would be beneficial. For nine months the outfit had lived on British field rations, which included canned meat or fish and tea. Fresh eggs, milk and fruit were not available. Ladies in Philadelphia sent out American seed so that the garden was expanded to a 36-acre plot which produced vegetables for most of the year, grown under sanitary conditions.

Dr. Ravdin also started to raise pigs for meat. According to Dr. North, he also put a soldier, who had been unable to do the simplest assignment in the hospital, in charge of a flock of geese. The Christmas dinner in 1944 featured roast goose.

Though everyone was expected to appear neat and clean, Dr. Ravdin showed great tolerance when it came to variations in military regulations and uniforms. A commanding officer with a regular army background would have been horrified at the sight of a field grade medical officer in shorts, bush jackets, and using umbrellas as protection against the sun, Dr. North noted. But Dr. Ravdin accepted these uniforms as being suitable for the occasion in such a hot climate.

Since the staff had been affiliated with the School of Medicine and everyone had a strong academic background, the hospital became a center for weekly professional conferences attended by American, British, and Indian officers from other medical installations.

"These meetings improved understanding and cooperation with the forward medical installations by reciprocal exchanges of medical officers," Dr. Wood said. "The outstanding characteristic of the unit was a spirit of steadfast devotion to the care of its sick and wounded patients."

Some 100 important medical papers and scientific reports were produced by the 20th General Hospital, including those on scrub typhus and ophtalmology.

On March 3, 1945, Dr. Ravdin received a much-deserved promotion to brigadier general and "with it the distinction of being the only general officer ever to command an overseas hospital in wartime."

Captain Harold Scheie was called upon to handle two especially unusual cases. In one he was asked to operate on the chief of a head-hunting tribe who had become blind with cataracts. Since these tribes had been a threat to reconnaissance soldiers and porters in the back country, the American military and the local British Civil Governor - a man by the name of Johnny Walker - with headquarters near the 20th General, conferred and felt that a more friendly atmosphere would develop with these tribes, if this chief could be made to see again.

Dr. Scheie said that this man, a real primitive, came down through the jungle trails to the hospital with a relative hanging onto the front of a bamboo pole guiding, and another at the back supporting, while the patient grasped the middle. He was wearing nothing but a loin cloth, and had bamboo spikes in his hair and earrings of bone hanging from his ears.

"To examine him I had to squat down the way he was squatting. He ate food by scooping it up with his hands. I performed the operation with a spear-holding honor guard standing suspiciously by. He did have a beautiful result in each eye and I was able to improvise glasses for him. The restoration of his sight was one of the most thrilling events of my professional life. Dr. George Hoffman in obstetrics was there with me watching this fellow. Here was a man from the jungle completely blind when he came down to us. We let him look out of our bamboo clinic across the hospital to see soldiers in uniforms and jeeps running around. He contemplated the scene for a minute or two, then he began to jump up and down and grunted with excitement. It was so touching that George and I both shed tears."

When he left, the doctors rolled up some packages of Lucky Strike cigarettes into brightly colored green and silver rolls, which he used to plug up the holes of his ears.

"They became one of his great treasures," Dr. Scheie said. "He was so appreciative of what had been done in this operation that he gave me 100 chickens and the promise of two wives." Dr. Scheie hesitated a moment then added, "No one ever asks me what I did with the chickens."

|

Dr. Scheie also found himself in the position of treating Lord Mountbatten, then serving as Supreme Allied Commander in Southeast Asia, for intraocular hemorrhage and corneal injury.

Lord Mountbatten had gone to visit the Northern Combat Area Command with General Stilwell, his deputy, who was in command of American, Chinese and British forces on that front. According to an account written later by Lord Mountbatten, he had left General Stilwell to have further discussions with his Chinese generals and had driven himself back in his jeep where soldiers were still busy clearing the way. As his jeep went over bamboo that had been felled, one, which must have been bent out by the front wheel, snapped forward and hit him in the left eyeball. He was knocked out of his seat and the jeep was momentarily out of control until he was able to switch off the motor.

He found himself completely blind in the left eye, and after putting on a first aid dressing, Captain Young, General Stilwell's Chinese A.D.C., who was with him, drove him back to Taipha Ga, where his personal Dakota aircraft and his staff were waiting.

They first went to Dr. Gordon Seagrave, who realized that the injury was "real trouble," as he termed it in his book, Return of the Burma Surgeon. "It was my certain duty either to send him back to Ledo by air to Captain Scheie, the ophthalmologist at the 20th General Hospital, or else be responsible for the loss of his eye," he wrote.

After Lord Mountbatten arrived at the 20th General Hospital, Captain Scheie examined his eye and seeing the extent of the damage, ordered him to cancel his tour. He bandaged both eyes and put him to bed in a basha hut where he watched his progress for the next five days.

Since Lord Mountbatten's aircraft was equipped with the most sophisticated communications system of the day, he was in contact with all the military establishment in the theatre.

"The main mission of our forces was to drive the Japanese back so that our engineers could build a road to connect into the Burma Road. Our intelligence reported that the Japanese were mounting a serious invasion of India of six or more combat divisions through the Imphal plain to cut off supplies to our combat engineers and to Merrill's Marauders, as well as to General Stilwell's Chinese forces who were also driving the Japanese back toward South Burma. If they had been successful in coming out into the Imphal plain it could have been devastating," Dr. Scheie said.

We learned that by then the Japanese had broken through the three main roads leading to the Imphal plain. Clearly, this was an emergency, which only I could adequately deal with," Lord Mountbatten wrote. "I decided I must go and visit the Army Command, General Slim, and Air Marshall Baldwin in Comilla, Near Calcutta, at once."

After explaining the urgency to Dr. Scheie, Lord Mountbatten asked if he would take the bandage off and let him go. Dr. Scheie asked for ten minutes to think the matter over. He was seriously afraid that Lord Mountbatten would lose sight of his eye for good if he took the bandage off and yet he realized the importance of this mission and knew there was no real choice, except to completely relieve the Commander's mind so that he could focus on the problems and decisions he would have to make in the next few days.

In communication with General Stilwell, Dr. Scheie was ordered to accompany Lord Mountbatten on his flight to this important meeting. Their plane set down at Comilla on a very hot day.

"It must have been 120 degrees, so that most of the meeting took place under the wing of the plane because the cabin was clearly too hot to use," Dr. Scheie said.

"I took the necessary steps to divert American transport aircraft off the famous 'hump' Kunming in order to transport the necessary British and Indian Divisions into the battle," Lord Mountbatten wrote. "The result was complete victory and the total annihilation of the Japanese. The failure to get the necessary transport aircraft in time could have meant the loss of an entire Army Corps."

After that meeting, Dr. Scheie was still under orders to stay with Lord Mountbatten and fly on to New Delhi until he could guarantee that his patient's eye needed no further care.

They climbed into the plane for the five-hour flight to New Delhi.

"In taking off, we flew over rice paddies and in that hot weather the air currents made it very choppy like being at sea in a fishing boat. Within 20 minutes I was acutely ill," Dr. Scheie said. "I've never been so humiliated. Lord Louis held my head for the next several hours, all the way to New Delhi. And I was supposed to be taking care of him. He never failed to remind me of this - especially at social gatherings later in our lives. He would take great delight in saying something like, 'Scheie, he's a great guy, but he's a very poor sailor. I'll never forget the time flying up from Calcutta when I was providing the care.' I've never been air sick since. That cured me.

The doctor-patient relationship under such conditions developed into a life-long friendship.

Henry Royster receives a decoration Henry Royster receives a decoration |

In the spring of 1983, some 90 of those who had been with the 20th General Hospital met again at Dr. Harold Scheie's apartment in Philadelphia for their 41st reunion. They reminisced and laughed together about the good times, forgetting the months of hardships and long hours they had endured to accomplish their mission.

Under the leadership of these and other Pennsylvania doctors, what was regarded as one of the toughest medical assignments in any theatre of the war became one of the most distinguished in terms of volume of patients, quality of service, and research produced.

The 20th General Hospital had been cited by Lord Louis Mountbatten, General Joseph Stilwell, Generals Sultan, Pick, Merrill, and the Commanding Generals of the 1st and 6th Chinese Armies. General Merrill's statement to a Philadelphia physician "You go back to Philadelphia and tell your people that the 20th General is the best damned hospital in the army," would have been citation enough.

From the collection of Colonel Charles S. Davis. Courtesy of Joe Davis. Page Revised: 05/30/2025

TOP OF PAGE THE 2Oth GENERAL HOSPITAL (PDF) HOSPITALS UNITS IN CBI THE CBI THEATER