|

|

|

|

At 2:41 A.M. on Monday, May 7, the German army surrendered. This was the moment the world had waited for through 2,076 days of war.

This was the moment of victory.

It came at the end of an incredible week. Each day the sun, rising over Europe in the east, looked down on the earth below and saw new climaxes. Moving westward, it saw first the people of Russia turbulent with such joy and relief as no great mass of people has ever known so suddenly. It saw the last bitter struggles in the hills of Czechoslovakia, where German rear guards ironically fought off one enemy so that their main force could flee to the less-dreaded mercy of another enemy. When the sun came over Germany it was a wonder that it did not stand still, as it did for Joshua when he battled the Amorites, for it saw events there which blotted out one function of the sun: the marking of time. The age of science, the 20th Century, the present time vanished. Instead there were images from Attila's times - men starved to death in prison enclosures, murdered, burned up in vindictive, final panics. There was an image from Wagner's myths: a blazing room in the Reich Chancellery in Berlin, a pyre for a fake god who may or may not have been consumed in flames. There was a flashback to Shakespeare: a tent on the blustery, rain-swept heath of Lüneburg where Montgomery, a man capable of Shakespearean fustian, said as he prepared to accept a surrender, "This is the moment!" - and then addressed the vanquished emissaries when they approached as if they were annoying intruders on an unknown errand, "What do you want?" Down in Italy the sun saw a tyrant hanging by his heels beside a woman to whose underclothes a locket was pinned with an inscription from the tyrant, "I am you and you are I" - an upside-down dictator groping for identity with a dead mistress in a crazy world. At the meridian called Zero the sun looked down on a London scarred by most complicated and evil inventions and on a stoic people at last released in victory. Beyond the ocean the sun saw a vast, productive country unsure what "victory" meant but joyous, noisy and hopeful; and on the western rim of the continent a parley of men squabbling over details when the future of humanity should have been in their throats. Out across the waters toward the end of its circling the sun came to a green island named Okinawa, where other men were fighting some more. |

|

|

|

For the U.S. Army these mass surrenders posed an increasingly serious problem. They did not have supplies to feed their prisoners, men to guard them, vehicles to take them to rear. But for the Allies' victorious leader the surrenders were cause for the highest kind of military satisfaction. "This," said Ike Eisenhower proudly, "is a battlefield surrender." |

|

Elsewhere in Hitler's Reich, Germans stopped killing others and began killing themselves. In Weimar the mayor and his wife, after seeing Buchenwald atrocities, slashed their wrists. In Nürnberg the local Nazi leader shot the mayor and then himself. In Berlin, where the Russians reported mass suicides, Propaganda Minister Goebbels' chief assistant said that even Hitler and Goebbels had killed themselves. Hitler, reports went, had shot himself; Goebbels had taken Poison.

|

|

|

"Lost" was the word that rang through Germany. To the German people, Hitler's war had been evil only because it had been lost. As the iron Nazi controls vanished and something like the air of freedom swept over Germany, a personal sense of being lost and alone overcame most Germans. It was too late, or too soon, for freedom. The German people had been literally ruined, in mind and heart. There were some who took out their humiliation in hating Hitler, crying that he had betrayed them. Others said that Hitler himself had been betrayed. But of feeling that Nazism itself was wrong, there was very little. In all Germany there was no real uprising, even at the last hour, against the Nazi masters. The world saw the awful and unprecedented spectacle of a people going down in despotism to utter defeat without the faintest attempt to break their bonds. Germany gave no evidence of knowing it was sick until it was dead. |

|

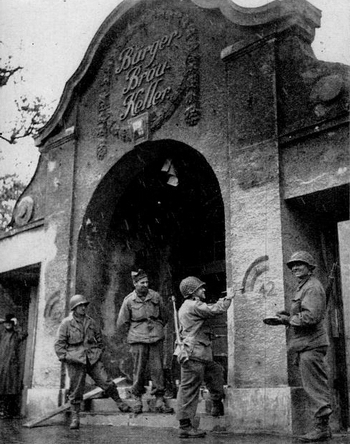

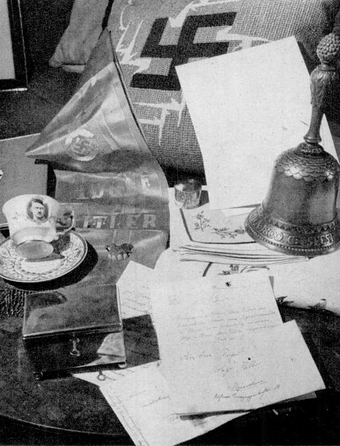

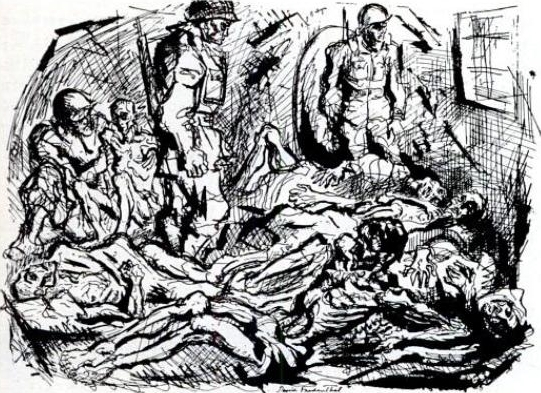

Munich was always Hitler's favorite city. In later years he spent most of his time strutting through the Chancellor's Palace in Berlin or his chalet at Berchtesgaden. But when he wanted privacy, he retired to his flat in Munich. He personally decorated it in his favorite baroque blue, white and gold. The apartment was filled with treasured possessions - a book from Himmler, a tea cup with his picture, false teeth (below). It was to Munich that 23-year-old Hitler, a frustrated Austrian, came in 1912. Here, after the war, he found his first fanatical followers. Here, 11 years later, he staged his abortive "beer-cellar putsch." Here, in 1938, he crowed over the democracies when he forced them to sign the Munich pact. And here, too, he may have met his end. On July 30, 1944, a clique of German generals tried to assassinate him. Edward W. Beattie, Jr., United Press war correspondent who was released from Nazi prison, reported that the German people believe that Hitler had been killed in Munich on that day. Whether he died then or later, this schism in high Nazi quarters definitely marked the beginning of Hitler's political end. The trappings with which Hitler had invested his myth were torn to shreds last week when, as these pictures show. Americans of the 42nd (Rainbow) Division brusquely invaded the precincts of the myth, trooped through the beer halls and banquet rooms which had been shrines of National Socialism. (At right) GIRL YOUTH LEADER, Elsa Wartz, 36, of Frankfurt-Höchst, struggles with anti-Nazi civil policeman in her cell - screaming, weeping, fighting. She had been arrested by the Allies because she had been responsible for all atrocities against females in Frankfurt-Höchst and had sent 600 children away in labor battalions. Her father, a Nazi Party leader, is also in jail. |

|

The collapse of the Nazi empire is a fantastic show. Germany is a chaos. It is a country of crushed cities, of pomposities trampled on the ground, of frightened people and also glad people, of horrors beyond imagination. Through the ruins of the great cities move the most motley crowds that Europe has seen since the Crusades. The greatest number are Germans. You can tell the Germans by their manner; they are stunned and tired and beaten and frightened; they start when spoken to; they smile timidly, ingratiatingly and beg information most humbly. Even a German in the greatest of distress does not stride boldly up to any American to ask for help or directions. He plucks your sleeve softly. In the ruins the Germans stand, cooking their meals on open-hearth, improvised brick ovens, readying the food to take down below into the innumerable caves and cellars they have been living in so long. Many of them have had no electric light or running water for a long, long time. They live like people will, perhaps, when the ice returns over the earth, huddled together for warmth and comfort and against loneliness, with someone outside in the night guarding the hole that leads down to their caves. In those caves life is exactly what you would imagine it to be: foul and pitiful, but at least warm and safe against the bombs and the terror outside. DISPLACED PERSONS But the ones who move with cocky assurance through the ruins are the thousands of DPs (the Army initials for displaced persons) who are now thronging out of Germany in a phantasmagoric pilgrimage, and endless wave of thousands of vengeance-minded slaves and war prisoners, pillaging and raping and burning their way through the towns and cities, hopelessly out of hand for days after their liberation, as the fighting troops move rapidly on and the expert but pitifully undermanned staffs of the Military Governments strive desperately to cope with them somehow. The Germans fear their former slaves with an almost insane fear and that fear is not misplaced. God help the German family that lives in an isolated farmhouse these days. At the very least the DPs commandeer all cars, motorcycles, bicycles, farm wagons, carts. Then they loot their way through houses, always looking first for liquor and then valuables and then for food and then for clothing. Into the cities have poured thousands of the liberated from the environs. The greatest number were Russians - virile, short, stocky, happy, and the vast majority of them beautifully drunk with liberated champagne, cognac, vermouth and even beer. For two days you would see them fighting and clawing, tearing the clothes from each other's back in an effort to crowd into an already jam-packed underground warehouse where the Nazis kept food and especially liquor. An American soldier would order them away but the happy, drunken DPs would merely give him the old Bronx cheer with a flutelike tone. Scores of them would thumb their noses at the lone soldier, who could only grin helplessly. If he fired a shot in the air they merely clapped their hands admiringly and crowded around him to offer him bottles of their stolen schnapps. PARADISE IN BASEMENTS The underground warehouses are the DPs paradise. I went down into several of these in Nürnberg. One had been a Nazi officers' sales store. This was actually more dangerous than small-arms fire because in the flickering candlelight hundreds of DPs were scrambling and fighting ferociously in the dark over each package, each paper carton, each shelf; scrambling like fat rats all over the floors in bales of paper, seeking they knew not what. Out of one office-building basement came a dozen DPs carrying German typewriters - great, heavy machines they are too, and solidly made. One of them had a small iron stove. One Russian girl on a bicycle was red-faced from pedaling under the weight of a mass of sausages tied together like a bunch of bananas. On her back were hung six bottles of wine. Everywhere in the ruins were bottles and everywhere on the streets was bottle glass. I walked in the pink dust that blew in sudden sandstorms into may face, my boots crunching over glass, piles of live and dead bullets of all sizes, and past the little drifts of torn Nazi uniforms and piles of German helmets and belts and ammunition cases. Around me were Russians, drunk and grinning and friendly, Belgians, Poles, hundreds and hundreds of Yugoslavs, Dutch and Italians. In the crowd I suddenly noticed a man with a yellow, six-pointed star on his breast pocket. On it was the word "Jude" (Jew). He told me he was the only Jew left in Nürnberg; that he had been unmolested because he had a German wife, but that all his family long since had gone off to concentration camps. He lived underground for six years, he said, and was not permitted any ration cards for food or clothing. He lived on what was smuggled to him by German friends of his wife. He vowed that today was his first carefree day in the open air for many years and certainly he breathed the stink of Nürnberg as if he were on the freshest peak in the Alps. Then I saw a spare, thin British soldier on a bicycle, Pvt. Sam Hewitt of the Cheshire Rifles, who had been a German prisoner since June 1940. His uniform, although faded, was freshly washed and neatly mended. He had bicycled in from the prison camp near the stadium. His reason was very British: he just wanted to see the sights of Nürnberg. He was pleased at the excellent destruction of the town but a little bit disappointed, too, for it looked like all other German towns. NÜRNBERG There are no cities left in Germany. Aachen, Cologne, Bonn, Koblenz, Würzburg, Frankfurt, Mainz - all gone in one sweeping reach of destruction whose like has not been seen since the mighty Genghis Khan came from the East and wiped out whole nations all the way from China to Bulgaria. Nürnberg, once a city symbolizing German culture, then Hitler's symbol of Nazi Kultur, is now no symbol of anything. Today Nürnberg looks like all the rest of the shells of cities, a great waste of broken bricks. From the burg on the hill in the inner walled city the vista is much like that looking down into Bryce Canyon in southern Utah, a stretching pink labyrinth of stone broken in fantastic shapes in canyons that wind about senselessly. We went in with a man who had lived in Germany many years, who knew Nürnberg well and had often attended Hitler's party congresses. He had his Baedeker guidebook with him to refresh his memory. From the start he was utterly bewildered. There were no landmarks to guide him: the huge railway station, the Grand Hotel, his favorite restaurants, all of them tuned out to be heaps of rubble when he finally, uncertainly, identified them. Very gingerly we entered the shell of the St. Sebaldus-Kirche, one of Nürnberg's famous churches whose construction spread over the 13th, 14th and 15th Centuries. A strong wind was blowing and from time to time big stones fell from the shreds of the vaulted roof far above. The whole church is gone except for one huge mass of reinforced concrete in the center where the Germans had bricked over the priceless shrine of Saint Sebald. From the top of a rickety 60-foot ladder you could see that this modern brick sarcophagus had held firm against the years of bombings and the days of shelling, with only a few cracks in the concrete. In the St. Lorenz-Kirche one such shrine also is safely walled up, guarded by a stone crucifix with the left arm shot away. The Liebfrauen-Kirche is utterly smashed and the famed entrance, which had also been walled over, suffered a direct shell hit that broke the reinforced concrete into powder. Above it there is no trace of the world-renowned Männlein Kraft clock, where every day at noon the seven electors came out of the clock jerkily and nodded their little metal heads in a stiff bow to the seated figure of Emperor Karl IV and filed back into the clock to await another noon. The massive Rathaus, or city hall, is entirely gone except for the shrapnel-chipped groups of caryatids at one end. The Bratwursthaus is obliterated; only a leaning, dusty poplar tree marks where it stood. The famous fountains are destroyed. The Hans Sachs house is gone, although the statue of the cobbler immortalized by Wagner in Die Meistersinger is there in the rubble. The house of Albrecht Dürer, the artist, has vanished. The Germanisches Museum and the tower near Burgberg, which held the "iron maiden" in whose spiky embrace many a victim of the Inquisition perished, are mere shells. The crown jewels of the ancient German emperors, which for centuries reposed in the city, are in some vault, perhaps. Over this sickening desolation hangs the pall of a city not yet done burning, with dark smoke where some old smoldering wood has been fanned up again and pink clouds of fine dust, brick dust that has been pulverized finer than sand, almost into talcum powder. And throughout the city is the smell of all such cities as they are conquered, a small compounded of many smells - of death first, of offal, of wood smoke, of gunpowder, and a sick-sweet smell that comes from thousands of opened bottles of wine and spirits half-drunk and then smashed on the ground.

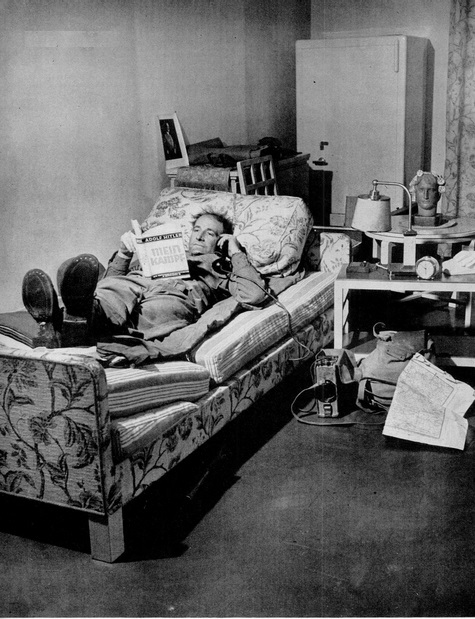

DACHAU The ruins in the cities are not nearly so horrifying as the ruins of humanity which you find in the prison and concentration camps. When all the other names of prison camps are forgotten, the name of Dachau will still be infamous. I entered the camp with the first American troops. Beside the main highway into the Dachau camp there runs a spur line off the main Munich railroad. Here a soldier stopped us and said, "I think you better take a look at these boxcars." The cars were filled with dead men. Most of them were naked. On their bony, emaciated backs and rumps were whip marks. Most of the cars were open-top like American coal cars. I walked along these cars and counted 39 of them which were filled with these dead. The smell was very heavy. I cannot estimate with any reasonable accuracy the number of dead we saw here, but I counted bodies in two cars and there were 53 in one and 64 in another. A German civilian rode his bicycle up beside us at this point. He was crying and trembling. He said he lived in a house near Dachau, but like most Germans had never believed all the stories about the camp until four days before. Then this trainload of political prisoners, evacuees from other prison camps moved here hurriedly by the SS, had been brought in and left on the siding. He said they moaned and cried night and day as they died of thirst and hunger and exposure. The weeping German didn't even care if the angry GIs around him killed him, he was so desperately, abysmally ashamed of being a German. As we walked back down to our jeeps a soldier suddenly shrilled, "Look, for Christ's sake, one of them's alive!" Out of the mass of bony, yellow flesh a figure sat up feebly. One of us jumped in the freight car and lifted the skinny thing out. The only way you could tell he was any more alive than the dead was that he could still move slightly. He could not even smile. But he was semiconscious. From the patch with capital letter P on his coat we knew he was a Pole. He weighed about 80 pounds, but was fairly tall. He was wearing only a short coat. We wrapped him in blankets, put him in a jeep and drove him back to a field hospital. Now we began to meet the liberated. There were several hundred Russians, Frenchmen, Yugoslavs, Italians and Poles, frantically, hysterically happy, many of them in blue-and-white-striped pajama-like uniforms. They began to kiss us and there is nothing you can do when a lot of hysterical, unshaven, lice-bitten, half-drunk, typhus-infected men want to kiss you. Nothing at all. We went on and the great size of the establishment of Dachau began to open up before us. Factory buildings and barracks and big administration buildings spread on and on, apparently endlessly. Outside one building, half covered by a brown tarpaulin, was a stack about five feet high and about 20 feet wide of naked dead bodies, all of them emaciated to the skeletal point. We went on around this building and came to the central crematory. The rooms here, in order, were 1) the office where the living and the dead passed through and where all their clothing was stripped from them; 2) the Brausebad room where the victims were gassed; and 3) the crematory. In the crematory were two large furnaces. Long grates were fixed to slide in and out, bearing the bodies.

Though we were tired, we were lured on and on and on from building to building. What lured us was a sound which at first we had thought was the wind in the pines of Dachau. Then after a while we knew it was cheering - the sound of thousands of men cheering and cheering again. Before us stretched the great prison compound of Dachau. Here swarmed the liberated men of Dachau. These men, cheering as hard as their feeble strength would permit, tore themselves getting through the barbed wire to touch us, to talk to us. Some of them were nearly mad with joy. Here were the men of all nations that Hitler's agents had picked out as prime opponents of Naziism; here were the very earliest Hitler haters. Here were the German Social Democrats, survivors of the Spanish civil war, a correspondent for the Paris-Soir who cried so hard I couldn't get his name. The cheering went on and we were forcibly mobbed by hundreds of men strong as only the half insane can be. One giant Russian held me for at least 30 seconds while he kissed all over the U.S. insignia on my coat. They shouted in all languages but sometimes in American phrases, such as one little Pole who ran beside us until he dropped flat, shouting desperately, "Hello boys!" “SIBERIA?” In the smaller towns the chaos is no less chaotic; only the scale is smaller. Lauda is a little town on the Tauber River in southern Germany. Each of its three tiny stone bridges over the Tauber is barely wide enough for cart traffic and big American trucks could barely squeeze past the ancient statues of Christ on the main bridge, a bridge constructed in the year 1378. The little town slumbers in the sun in a cloud of apple blossoms and smells richly of cow manure. A middle-aged German woman did my laundry in one of the little houses that cluster together behind masses of lilacs. She did a great bag of laundry for me three times, and each time charged me what she obviously regarded as the maximum: three marks, which equals 30¢. She did it beautifully, too. The last time I went there when she knew we were moving out of town, she h=gathered her young daughter and her grandson close behind her and nerved herself to ask the big question that had obviously preyed on her mind for some weeks: "When are you going to send us all to Siberia?" SHOESTORE IN AICHACH We drove into Aichach, some thirty miles south of the Danube, just as the last snipers were being cleared from the far end of town by troops of the 42nd Division. At our end a captain of Military Police was telling his men, "We will set up the information booth on this corner." As we drove down the street we met about 15 Belgians who had not been liberated more than 30 minutes. All of them were carrying boxes of shoes. A little farther a small riot was going on in and around the town's main shoe store. We crowded our way in to find the whole store had been stripped almost completely of its stock while the frantic Germans ran around wailing and wringing their hands. The proprietor, a middle-sized, balding German about 40 was especially frantic and was outraged that the Americans would permit such things. We asked him if he had not heard that the German army itself had done such things in France, Belgium, Greece, etc., etc. He drew himself up proudly and said, "Sir! The German army would never stoop to such things!" We asked him mildly how he knew and he said, "I was a soldier myself." Still mildly we asked to see his Soldbuch, the little service-record book all German soldiers must carry. This was most interesting; it showed that he had been discharged from the army that very morning, Sunday, April 29. He had gone to his commanding officer, told him that he was in his own home town and that the war was over and that he wanted to go back into the shoe business. This seemed sound to his CO, who discharged him honorably. He had then changed clothes and played his violin for the first time in several years, getting ready for Monday's show trade.

GERMAN PRISONERS The last two weeks of April and the first days of May have been very cold in Bavaria, with occasional snow and sleet storms driven by high winds. Down the superb Autobahn marched a column of German soldiers several miles long, plodding steadily into the driving sleet. These were the defenders of Munich. Each company was guarded by only two doughboys, and one American jeep moved slowly at the head and one at the tail of the column. The Germans had that disheveled look that all soldiers get the moment they become prisoners, weaponless, often hatless, unbuttoned and beltless. Despite their obvious fatigue most of them seemed happy. Many were smiling; many waved at our jeep as it passed. Some were women, but these were the equivalent of our WACs. Many of these prisoners had been clerks in the equivalent of our SHAEF until a few days ago and had never fired a gun in anger. Most of them looked as if they didn't have a care in the world now that their greatest care - the fear of death - had been removed. They slogged off into the sleet. They looked as if they would gladly have sung a song if it had been permitted. THE BROWN HOUSE In Munich an officer in charge of counter intelligence referred to his latest secret sheet of information. His unit had moved in only a few hours before. He riffled the pages to the latest report on the condition of Hitler's famed Brown House. The sheet said "apparently intact." We rushed over to the spot that was so sacred to the Nazis; it was only a few blocks away. All that was left were parts of three walls and a fine pile of rubble from which some radio correspondents were making broadcasts, surrounded by embarrassed GIs. MUNICH Munich is gay, almost Parisian. Here the people welcomed the Americans as liberators, and they really meant it. Again and again and again the Germans said, "We have waited so long for you to come," or "You have taken so long to come!" Somewhat fed up, the Americans usually answered, "Well, we had a long way to come." In Munich the tankers carried lilacs on their tracks. The women were very numerous, very accessible and often very attractive. In Munich it was astonishing to find how many women came up to you with little notes, saying in effect, "Please take good care of Fräulein Anna Blank. She was very good to me and helped me in my escape and is a friend to all Americans. Signed by an American prisoner of war." In Munich the famed Munich beer was very poor. But the warehouse cellars were so full of champagne that the soldiers and the liberated prisoners were still hauling it out days after Munich fell. The liberes had an excellent system for handling the throngs who crowded into these cellars and came out many minutes later lugging bags and boxes full of liquor of all kinds. Usually they opened a small office at the head of the stairs and then took charge of the single file which was returning with staggering loads. Soldiers and Russians, Frenchmen, Poles, etc., were permitted to carry out their loot without hindrance, but all German civilians were firmly relieved of their loads. In this way much labor was saved since it was a long haul out of those underground caves.

Six days before Munich was taken, two American prisoners escaped to the 42nd Division. They told us that the camp commandant, a Nazi named Captain Mulheim, spoke good American slang and was a nice guy. They said he made a speech to them several times in almost exactly these words, "Now lots of you guys are going to try to escape. Lots of you are going to make it. I just want to impress on you one thing; when you escape, make it good and keep on going. Stay in the woods and travel by night and go toward the Rhine. We will probably catch you all right. But what I mean is this: that kind of escape is honest and I won't be hard on guys that really are trying. But for God's sake don't just go into Munich and shack up with those Munich whores. They'll just turn you in after a while. I'll be rough on any guys we catch who've been shacked up with those girls." The escapees said he was as good as his word. They also said that cigarets were the real money of the camp at Munich. They swore that for one cigaret you could get a bar of soap, for 20 cigarets you could get a woman, for 50 cigarets you could get plenty of liquor and for 2,000 cigarets you could meet a man in Munich who would conduct you safely all the way to the Swiss border. They insisted this was true and gave the name of one American air force officer who had a standing offer: he would give %500 for 500 cigarets, which was all he needed to complete the necessary 2,000 for his escape. The PWs got their cigarets from their Red Cross packages twice a week. THE SS MYSTERY The mystery of where the SS has gone is being cleared up steadily. They have gone into civilian clothes and are seeping back into the little German towns. Yesterday eight of them were caught in Dillingen, a pleasant little town on the Danube, when some blue-turbaned Hindu ex-prisoners recognized the men who used to hit them with rifle butts in their prison camp. The screening of all German civilians by the Military Government is necessarily very slow as it is an enormous job for a small outfit and Germany is a big place in which to hide. Meanwhile it's a very odd feeling to walk through streets in which are many husky, tanned, brutal-looking Germans in civilian clothes who stand about rather stiffly or bicycle past you with averted faces. SOFT PEACE vs. HARD PEACE The conflicts now seething within American soldiers between their hatred of Germans and Germany and Naziism, and their natural Christian upbringing and kindness and susceptibility to beautiful children and attractive women and poor old ladies, is one of the great stories of today. The same doughboys who went through Dachau's incredible horrors were the very next day being kissed and wreathed in flowers by the German women of Munich. Some doughboys say they hate all the Germans, and they obviously do; and yet others who have been through just as much bitter fighting and obvious trickery will tell you that they hate only the Nazis and they like many Germans. I heard one say, "I even want to shoot all the pregnant women because I know that what's in their bellies will someday be shooting at my children." His buddy was giving candy to a little German girl while he was speaking. THE JOB OF UNLEARNING Few Germans in the ruined great cities, which are so close to plagues of typhus and where the Germans get thinner every day unless they move to their friends in the country, can yet realize the place of Germany at the bottom of the list of civilized nations. They learn with shock and shame of the American nonfraternization policy. Many of them simply cannot understand it. They thought they were fighting in an honorable war. When parents realize that they lost all their sons in a cause unspeakably dirty they are filled with a despair that will mark the rest of their lives. Of course they should have realized it years ago when they were heiling the Führer. But they lived two lives, they say, one of exaltation at his great political promises of the wonderful new Germany to come, and one of terror that the Gestapo might knock on their door that night. And yet it is clear that Josef Paul Goebbels did the job he set out to do all too diabolically well. But the over-all, inescapable fact is that the German people are so solidly, thoroughly indoctrinated with so much of the Nazi ideology that the facts merely bounce off their numbed skulls. It will take years, perhaps generations, to undo the work that Adolph Hitler and his henchmen did. |

Benito Mussolini who, as the first Fascist dictator, foisted a pattern on the world, was also the first dictator to die. This is how: On April 25, with the collapse of his long-time support, Germany, he fled north from Milan where he had headed an important Fascist republican government. After Switzerland refused him entry, coldly revengeful Italian Partisans found him in a hill cottage near Dongo and meted rough justice. "Let me save my life and I'll give you an empire," cried Mussolini. Instead, at a brief trial he, his mistress and 16 other Fascist leaders got death sentences. "No, no," breathed Mussolini, staring into machine guns which then fired. A moving van carried his and the other corpses back to a Milan public square. Next morning thousands packed it to sneer at a one time swaggerer, to spit in his face and to crunch his belligerent jaw with kicks. Presently the bodies were strung up by their heels outside a filling station; then they were cut down, hauled to potter's field and buried in unmarked graves. (At right): CHEAP PINE COFFIN, filled with wood shavings, is the last couch of the battered dictator who in life loved ostentatious pomp. Here the body lies in the mortuary before burial.

|

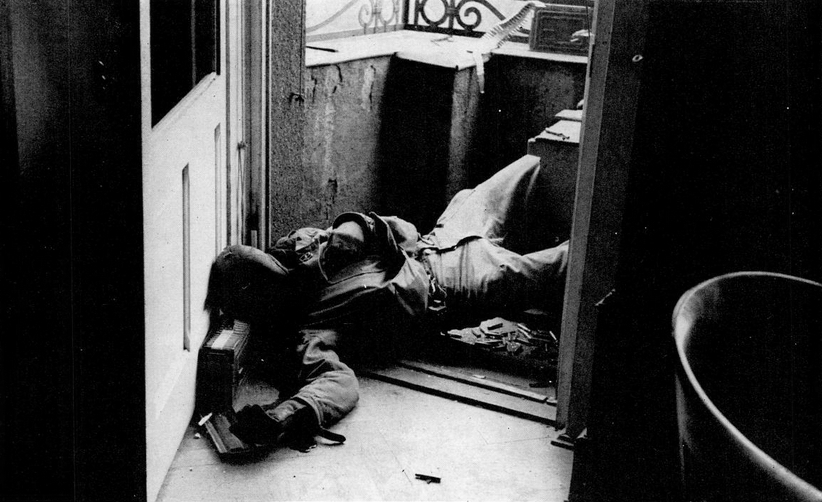

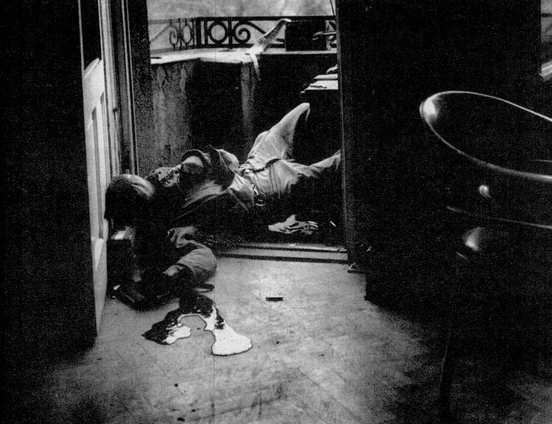

Until the very last moment of the war Allied soldiers were losing their lives in Europe. All during last week, with surrender rumors everywhere and the big battles over, Americans were still dying in mopping-up operations and in street fighting. During the finals days of the war a platoon of machine gunners entered a Leipzig building looking for positions to set up covering fire points which would protect foot soldiers of the 2nd U.S. Infantry advancing across a bridge. Two members of the platoon found an open balcony which commanded an unobstructed view of the bridge, set up their gun. For a while one soldier fired the gun while the other fed it. LIFE Photographer Robert Capa,

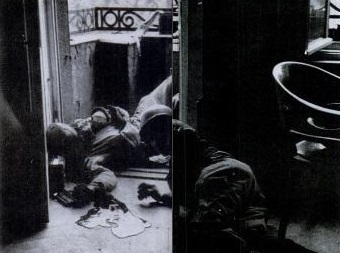

Other members of the platoon decided to find where the fatal shot had come from. Stealthily they single-filed onto the cobblestone street and surrounded Germans barricaded in several abandoned streetcars. They fired a few warning shots. Presently two Germans came out with their hands up shouting, "Kamerad!" The Americans, feeling no elation, took them away.

|

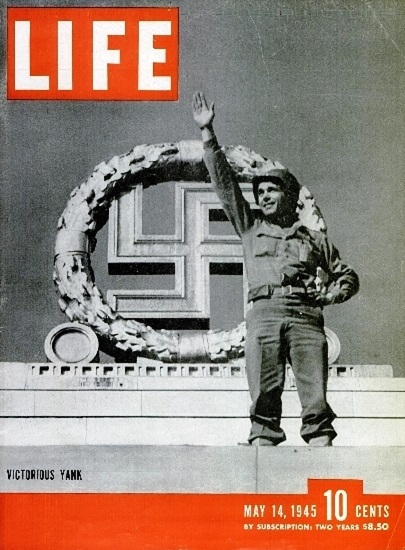

LIFE'S COVER: The American soldier on the cover - a Virginian named Strickland - is one of the millions of GIs who have won the victory in Europe. When LIFE Photographer Robert Capa took this picture, Strickland's detachment had just captured Nürnberg, Nazidom's shrine. This was a historic moment. But having just made history, Strickland proceeded to mock it. In a stadium where Hitler had often stood, he raised his right hand and, with a burlesque Nazi salute, proclaimed a GI's razzing epitaph on Hitlerism.

80th Anniversary 1945-2025

Adapted from the May 14, 1945 issue of LIFE

Portions copyright 1945 Time, Inc.

FOR PRIVATE NON-COMMERCIAL HISTORICAL REFERENCE ONLY

TOP OF PAGE CLOSE THIS WINDOW

GOOGLE BOOKS OLD LIFE MAGAZINES

VISITORS

TO ESCAPE RUSSIANS , Germans paddle across Elbe River to be interned by the Allies. Many made their own crude boats and rafts, others swam to west bank.

TO ESCAPE RUSSIANS , Germans paddle across Elbe River to be interned by the Allies. Many made their own crude boats and rafts, others swam to west bank.

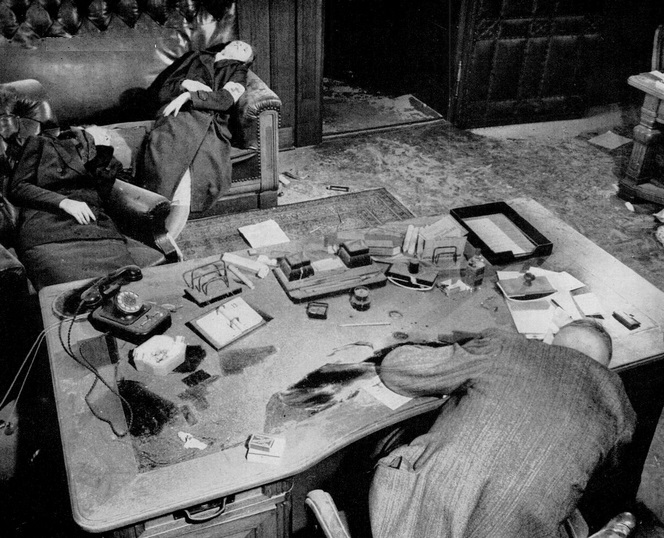

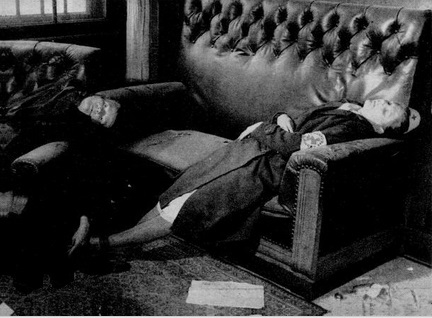

DAUGHTER REGINA LISSO WORE HER GRAY RED CROSS UNIFORM TO DIE

DAUGHTER REGINA LISSO WORE HER GRAY RED CROSS UNIFORM TO DIE

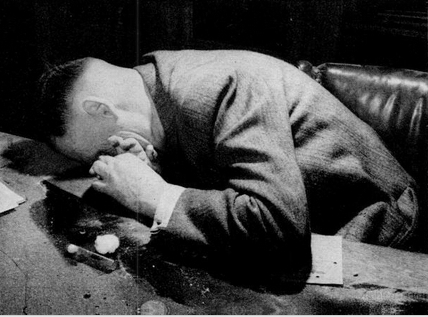

KURT LISSO, A LOYAL HITLERITE, DIED WITH HIS NAZI PARTY CARD AT HIS ELBOW

KURT LISSO, A LOYAL HITLERITE, DIED WITH HIS NAZI PARTY CARD AT HIS ELBOW

TWO DEAD CHILDREN

on parlor floor of a middle-class Schweinfurt home are covered with a sheet by a neighbor. The mother of these children, hearing that her soldier husband had

just lost his life fighting in the outskirts of Schweinfurt, killed them and the shot herself.

She probably put the bandages over their eyes first. The mother's body was found in the cellar.

TWO DEAD CHILDREN

on parlor floor of a middle-class Schweinfurt home are covered with a sheet by a neighbor. The mother of these children, hearing that her soldier husband had

just lost his life fighting in the outskirts of Schweinfurt, killed them and the shot herself.

She probably put the bandages over their eyes first. The mother's body was found in the cellar.

GERMANS LINE UP

for frozen vegetables at one of Frankfurt's new food stores after occupation. With all Europe, Germans face certain hunger.

GERMANS LINE UP

for frozen vegetables at one of Frankfurt's new food stores after occupation. With all Europe, Germans face certain hunger.

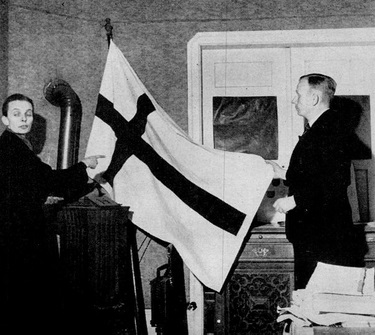

CONFESSIONAL CHURCH FLAG, banned for past 12 years, is unfurled at last by Frankfurt anti-Nazis, the wife of Pastor Karl Goebels, and Pastor Reinhard Ring.

CONFESSIONAL CHURCH FLAG, banned for past 12 years, is unfurled at last by Frankfurt anti-Nazis, the wife of Pastor Karl Goebels, and Pastor Reinhard Ring.

AMG GOVERNOR, Colonel Crisswall, in Frankfurt, speaks his mind to the new Frankfurt city council because it had allowed stores to open without being investigated and

licensed by the AMG.

AMG GOVERNOR, Colonel Crisswall, in Frankfurt, speaks his mind to the new Frankfurt city council because it had allowed stores to open without being investigated and

licensed by the AMG.

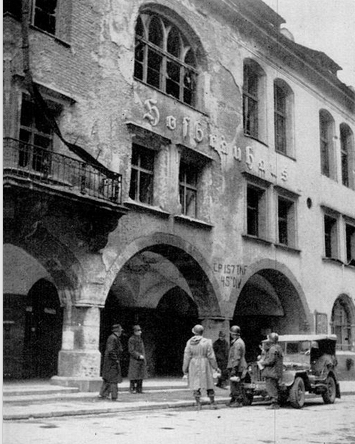

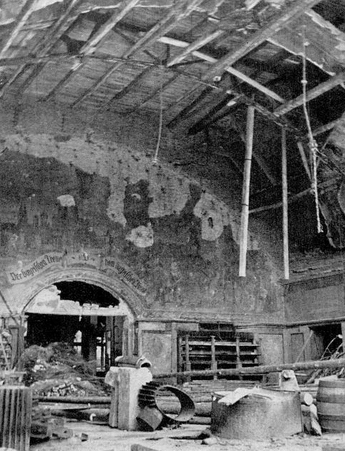

HOFBRÄUHAUS, where Nazi Party was founded in 1920, gets once-over from U.S. soldiers. Previous Yanks have left marks on wall.

HOFBRÄUHAUS, where Nazi Party was founded in 1920, gets once-over from U.S. soldiers. Previous Yanks have left marks on wall.

ENTRANCE OF HOFBRÄUHAUS is piled with wooden chairs which were once laden with Nazis, now with dust. Nazi banner is suspended

from balcony.

ENTRANCE OF HOFBRÄUHAUS is piled with wooden chairs which were once laden with Nazis, now with dust. Nazi banner is suspended

from balcony.

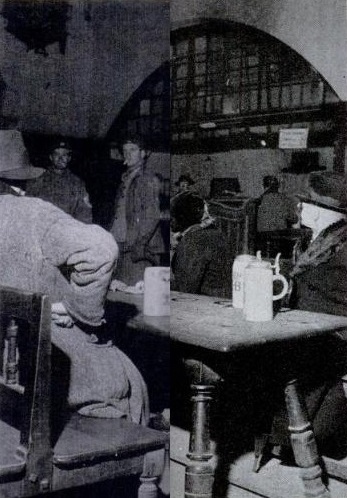

BEER CELLAR in Hofbräuhaus is still open. Two civilians drink beer at the table and U.S. soldier is having one at the bar.

BEER CELLAR in Hofbräuhaus is still open. Two civilians drink beer at the table and U.S. soldier is having one at the bar.

BÜRGERBRÄU KELLER (citizens' beer cellar) is where Hitler staged putsch in 1923 and proclaimed the "National Revolution."

BÜRGERBRÄU KELLER (citizens' beer cellar) is where Hitler staged putsch in 1923 and proclaimed the "National Revolution."

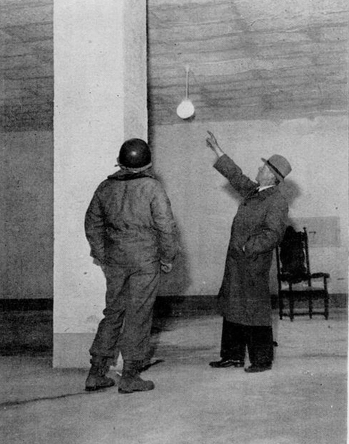

ASSASSINATION ATTEMPT by generals against Hitler last year occurred in this room of Bürgerbräu.

Guide points to pillar where the bomb was concealed.

ASSASSINATION ATTEMPT by generals against Hitler last year occurred in this room of Bürgerbräu.

Guide points to pillar where the bomb was concealed.

BÜRGERBRÄU CELLAR houses statuettes including swastika in wheel and Horst Wessel figure (right of swastika).

BÜRGERBRÄU CELLAR houses statuettes including swastika in wheel and Horst Wessel figure (right of swastika).

BOMBED BANQUET HALL of Hofbräuhaus has damaged mural of Munich over rear doorway with inscription:

"To Bavarian loyalty and Bavarian drink."

BOMBED BANQUET HALL of Hofbräuhaus has damaged mural of Munich over rear doorway with inscription:

"To Bavarian loyalty and Bavarian drink."

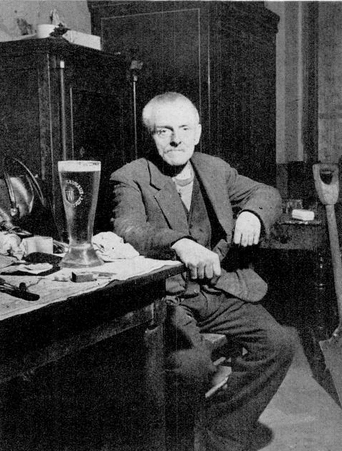

JANITOR at Hitler's headquarters, Wilhelm Guillon, 76, sits at original party council table with beer stein.

He waited on Hitler in 1921.

JANITOR at Hitler's headquarters, Wilhelm Guillon, 76, sits at original party council table with beer stein.

He waited on Hitler in 1921.

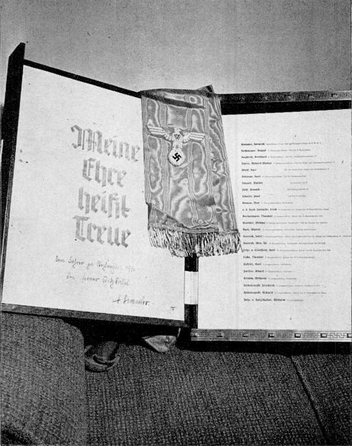

SS BOOK signed by Himmler reads, left, "My honor is loyalty." Dedication is "To the Führer,

Christmas 1936 from his SS." Right-hand page lists top Nazis.

Guide points to pillar where the bomb was concealed.

SS BOOK signed by Himmler reads, left, "My honor is loyalty." Dedication is "To the Führer,

Christmas 1936 from his SS." Right-hand page lists top Nazis.

Guide points to pillar where the bomb was concealed.

HITLER MOMENTOS in his Munich flat include stationery, swastika pillow, teacup with picture, letters, false teeth,

big dinner bell.

HITLER MOMENTOS in his Munich flat include stationery, swastika pillow, teacup with picture, letters, false teeth,

big dinner bell.

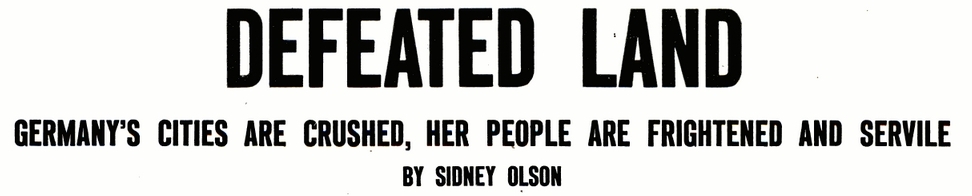

ON HITLER'S BED in Munich lolls a U.S. sergeant named Arthur F. Peters of Edmond, Okla., perusing Mein Kampf.

Like GI on cover, Peters was performing an act which not long ago in Germany would have been punished as desecration.

The evil dreams which had haunted this room had driven Germany to destitution and destruction reported on the following pages.

ON HITLER'S BED in Munich lolls a U.S. sergeant named Arthur F. Peters of Edmond, Okla., perusing Mein Kampf.

Like GI on cover, Peters was performing an act which not long ago in Germany would have been punished as desecration.

The evil dreams which had haunted this room had driven Germany to destitution and destruction reported on the following pages.

CORPSES hang from a gas station girder: (from left) Clara Petacci, Mussolini, Achille Starace, ex-secretary of

Fascist Party. Grunted an onlooker, "Mussolini has at last become a pig."

CORPSES hang from a gas station girder: (from left) Clara Petacci, Mussolini, Achille Starace, ex-secretary of

Fascist Party. Grunted an onlooker, "Mussolini has at last become a pig."

THE FIRST DICTATOR'S BODY (sprawled at lower right) still wearing Fascist militia gray and green, lies where

he was tossed in Milan's Piazza Loreto, his booted feet tangled with those of a dead henchman, his shaven head resting on the breast of his beauteous, 25-year-old

mistress, Clara Petacci. Armed Partisans had to fire warning shots to restrain the leering crowd.

THE FIRST DICTATOR'S BODY (sprawled at lower right) still wearing Fascist militia gray and green, lies where

he was tossed in Milan's Piazza Loreto, his booted feet tangled with those of a dead henchman, his shaven head resting on the breast of his beauteous, 25-year-old

mistress, Clara Petacci. Armed Partisans had to fire warning shots to restrain the leering crowd.

IN LEIPZIG TWO AMERICAN SOLDIERS SET UP AND FIRE A MACHINE GUN FROM A HIGH BALCONY. LIFE HAS BLANKED OUT THEIR FACES TO PREVENT IDENTIFICATION.

IN LEIPZIG TWO AMERICAN SOLDIERS SET UP AND FIRE A MACHINE GUN FROM A HIGH BALCONY. LIFE HAS BLANKED OUT THEIR FACES TO PREVENT IDENTIFICATION.

A MOMENT LATER A BULLET FROM THE GUN OF A GERMAN SNIPER STRIKES THE SOLDIER (ON LEFT IN PICTURE AT LEFT) SQUARELY BETWEEN THE EYES.

A MOMENT LATER A BULLET FROM THE GUN OF A GERMAN SNIPER STRIKES THE SOLDIER (ON LEFT IN PICTURE AT LEFT) SQUARELY BETWEEN THE EYES.

BLOOD STARTS FLOWING FROM SOLDIER'S FOREHEAD FORMING POOL ON FLOOR. HE DIED INSTANTANEOUSLY.

BLOOD STARTS FLOWING FROM SOLDIER'S FOREHEAD FORMING POOL ON FLOOR. HE DIED INSTANTANEOUSLY.

ANOTHER GI CRAWLS OVER TO MAKE CERTAIN THAT NOTHING MORE CAN BE DONE FOR HIT SOLDIER.

ANOTHER GI CRAWLS OVER TO MAKE CERTAIN THAT NOTHING MORE CAN BE DONE FOR HIT SOLDIER.

THE GUN IS MANNED AGAIN. DEAD SOLDIER'S PAL TAKES HIS PLACE ON BALCONY WHILE OTHERS SEEK SNIPER.

THE GUN IS MANNED AGAIN. DEAD SOLDIER'S PAL TAKES HIS PLACE ON BALCONY WHILE OTHERS SEEK SNIPER.