The overriding concern of U.S. planners when it came to Southeast Asia in World War II was to keep China in the war.

|

The immediate question was how to pursue the war on the Asian continent in the face of sharply conflicting views

|

Major General Claire Chennault, installed as commander of the 14th Air Force in China, plugged for a strategy of

victory by air. Earlier in the war, Chennault's American Volunteer Group (AVG) of fighter pilots, the "Flying

Tigers," had valiantly held off superior numbers of Japanese planes. Now he insisted that with 150 combat planes

and adequate air supply, his fliers could defeat Japan. President Roosevelt and Churchill were impressed at first,

then foresaw the down side - less than two years later, Japanese troops overran many U.S. airbases in China,

including the one from which the B-29s had first bombed Japanese cities.

|

A New Land Link to China

Lieutenant General Joseph W. Stilwell, Commander of the China-Burma-India Theater of Operations, emerged as the winner when the Allies finally agreed to a ground offensive. His directive was to break the Japanese blockade by opening a new land link to China. This would involve driving Japanese forces from northern Burma so U.S. Army Engineers could build an all-weather road from Ledo, Assam, in India to connect with the old Burma Road near the Chinese border.

Stilwell had been preparing the way since early 1942, when as Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek's army commander, he led a humiliating retreat out of Burma in which thousands died, acknowledging that "We got a hell of a beating," and vowing to return in triumph. Soon after reaching India, Stilwell put a U.S. engineer battalion to building the

|

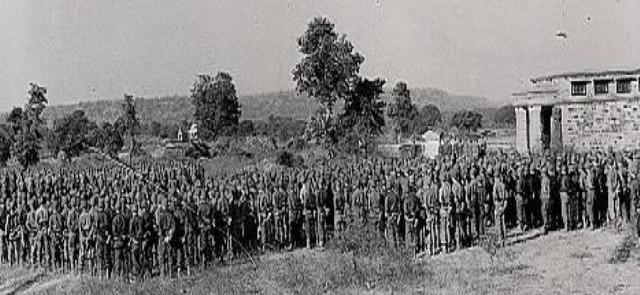

The Allies' main force for the Allied offensive was a Chinese one, centered around the same troops Stilwell had commanded for Chiang Kai-shek. He obtained agreement from the Generalissimo for American instructors to train in India the 9,000 Chinese soldiers who had retreated from Burma, plus another 23,000 flown in from China over the Hump, to create three complete infantry divisions. Stilwell maintained that Chinese soldiers, if properly trained, equipped, fed and led, would be the equal of soldiers anywhere. But he had reason to think otherwise when one of his Chinese divisions stumbled badly in its first brush with Japanese forces. Chinese officers then showed a lack of aggressive leadership. Their troops proved slow and cautious, and as Stilwell noted, "fearful of going around" enemy flanks. Efforts to correct these flaws made little headway. There was even evidence that Chiang Kai-shek was cautioning Chinese commanders not to risk their men unduly.

Stilwell had earlier tried to get Washington to shake loose an American infantry division to spearhead his campaign, but all were earmarked for Europe or the Pacific. Now he learned that a new U.S. regimental-size outfit had arrived in India to join the special British and Indian force of British Major General Orde Wingate known as the Chindits.

|

Stilwell responded to news of the 5307th's presence by pleading hard and successfully to General George C. Marshall,

Army Chief of Staff, to get this unit - trained in "going around" the enemy - transferred to his command. Within a

month, the 5307th was on its way, dubbed "Merrill's Marauders" by the press after the name of its new commander,

Brigadier General Frank D. Merrill, an ex-intelligence officer who had become a Stilwell sidekick on the walk out

of Burma. Stilwell also ordered a major change in how the Marauders would be used - no longer Chindit-style long-range

penetration, operating apart from front-line units, but medium-range penetration in close support of Stilwell's

Chinese infantry. Increasing their mobility, the Marauders would be supplied entirely by airdrops every few days

everywhere they went on the march, whereas the Chinese and Japanese had to rely on truck convoys that restricted

their movements outside the few roads through Burma's main river valleys.

Huge Impact of Merrill's Marauders

Merrill's Marauders made an impact on the Burma campaign that far outweighed their numerical strength as the only American infantry regiment in Asia. They opened with a wide end run around the right flank of the elite Japanese 18th Division, through the jungle near the top of the Hukawng River valley, to spring a road block on an enemy supply base at Walawbum. The enemy responded with repeated banzai attacks, which had served them well in conquering Singapore and Rangoon, only to suffer 800 killed by well-dug-in Marauders, many of whom had already fought the Japanese in Guadalcanal and New Guinea. With the enemy forced to pull back to meet the threat, the Chinese advanced more in three days than in the previous three months; but they then failed to follow through by finishing off the routed Japanese troops. Weeks later, the Japanese commander, stung by two more American road blocks, retaliated by trapping a Marauder battalion for several days in a hilltop village, only to suffer heavier losses when the Marauders used two air-dropped pack artillery pieces to devastating effect. Most of the Chinese troops meanwhile were left behind fighting the main body of the enemy.

|

The long march and heavy fighting behind Japanese lines, sustained only on emergency K rations, took a high toll among the Marauders. Three months in the jungles and mountains had reduced their original force by half, with two thirds of the casualties coming from tropical disease. Merrill had just gone out with a heart attack, replaced by his executive officer, Colonel Charles N. Hunter, and the Marauders' biggest test lay ahead. The Allied timetable called for Stilwell to take the key city of Myitkyina and its coveted airbase - which enemy fliers had used to shoot down U.S. transport planes on the Hump airlift - before the monsoons set in. It was then too late to stage this advance against the tenacious enemy through the chain of river valleys. However, natives revealed the existence of a little-known pass 5,900 feet high in the Kumon Range. Unused for 10 years, the steep path was reported to be almost impassable. Stilwell decided that the Marauders were the only ones capable of leading the way. The drenching summer rains had begun, making the footing so slippery that footholds had to be cut for the Marauder mules. Even so, some mules plunged to their deaths. The tortuous climb up and down the mountain, with combat teams leading Chinese and Kachin soldiers, took 19 days.

Once the weary Marauders sprang their surprise takeover of Myitkyina airbase - a feat hailed as Stilwell's greatest

victory - Merrill had promised quick evacuation. Stilwell refused to relieve them when he could not immediately

muster enough other troops to capture Myitkyina city, itself, in the face of a major enemy buildup. That required

another three months of bitter fighting, and the arrival of long-awaited American reinforcements and some Chindits.

By then, only 200 of the original Marauders were left standing. Their successors, soldiers of the Mars Task Force,

carried on heavy fighting to the Chinese border.

Unsung Heroes: The Nisei Interpreters

The unsung heroes of Stilwell's campaign - their presence then kept secret - were a small group of soldiers of Japanese-American parentage, the Nisei interpreters. Their families, by order of President Roosevelt, were interred behind barbed wire as "security risks" in California for the war's duration. However, these young Nisei had volunteered to join the U.S. Army and then volunteered for this particularly risky mission. They soon established themselves as special by their bravery and enterprise. The star of the Nisei group was Sgt. Roy Matsumoto, who early on climbed a telephone pole behind Japanese lines to tap into enemy calls, learned the exact whereabouts of a large ammunition dump, and radioed the coordinates to an American fighter squadron, which soon targeted the ammunition dump in a huge explosion.

When Matsumoto's battalion was later besieged for days by an enemy force, he crept close to the lines every night to listen for clues from jabbering Japanese soldiers to the times and places of their next day's attacks. His Marauder platoon leader, learning one night through Matsumoto of a big one coming, acted by ordering the Marauders

|

The ruling strategy in conducting the campaign in China-Burma-India might have been summed up in the words: "Make Do." With Europe and the Pacific getting top priorities on both military manpower and weapons, shortages of these challenged CBI commanders to adjust in all sorts of ways. A prime example of "make do" emerged when a shipment of Stuart M-3 light tanks arrived in India - but without Armored Force personnel to maintain and man them. Luckily, Stilwell's staff included a gung-ho former Armored Force officer, Colonel Rothwell Brown. The Colonel quickly came up with a brand new entity, the First Provisional Chinese-American Tank Group. To train and lead the outfit, he found a number of officers and GIs happy to leave engineering and transportation battalions. For tank crews, the Colonel drew upon the ranks of raw Chinese conscripts flown in to serve in the infantry. Almost none had driven a motor vehicle, much less entered a tank - and they had only three months to shape up for combat.

Yet Colonel Brown's mini-tank force soon managed to put such continuing pressure on the enemy in support of Chinese

troops as to play a valued part in the Allied effort. Their light tanks proved so vulnerable that they suffered

heavy losses. However, 12 Sherman medium tanks later arrived, to be manned by the American volunteers, and supplied

just the extra muscle needed. When Stilwell's troops finally drove through to connect their new road at the Chinese

border to the old Burma Road to Kunming, there were tanks of the First Provisional Chinese-American Tank Group to

clear away the last enemy.

Great Significance of the Engineers

What distinguished the ground campaign in the China-Burma-India Theater of Operations from all others where World War II

|

|

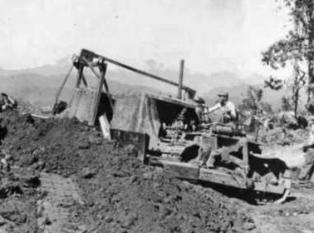

As work on the road progressed, the engineers experienced mounting casualties, not only through construction accidents

and disease, but by enemy action. Attacks by snipers and patrols became such a danger that bulldozers sometimes

carried a man riding shotgun. When the enemy threatened to retake Myitkyina, Stilwell ordered in from the road a

battalion of combat engineers, many of whom were wounded or killed. All told, some 130 engineers lost their lives

to the Japanese. Despite all problems, the engineers managed to push the road forward by a mile or more a day. By the

time it was finished, the war had only seven months to go. In that time, more than 5,000 vehicles made the 1,100-mile

trip, carrying 34,000 tons of vital supplies to China. Beside the road, a new pipeline opened, bringing oil and gas

to a nation that for years had to rely for its scant supplies on tanker planes. The United States had achieved its

goal of keeping China in the war, thereby tying up substantial Japanese forces on the Asian mainland and speeding

the day of peace in the Pacific.

TOP OF PAGE

PRINT THIS PAGE

CLOSE THIS WINDOW

Special thanks to Kermit A. (Tony) Bushur for providing the article on which this page is based.

Originally published in Nimitz News, a publication of

The National Museum of the Pacific War

Adapted for the internet by Carl Warren Weidenburner