For use of Military Personnel only. Not to

be republished, in whole or in part, without

the consent of the War Department.

Prepared by

SPECIAL SERVICE DIVISION, ARMY SERVICE FORCES

UNITED STATES ARMY

WAR AND NAVY DEPARTMENTS

WASHINGTON, D.C.

I claim we got a hell of a beating.

We got run out of Burma and it is humiliating as hell.

I think we ought to find out what caused it, go back and retake it.

THOSE WORDS of a famous American soldier carried all the way around the world when the last of the Allied forces

retreated from Burma into India during the first stages of the war in Asia.

The speaker was Lt. Gen. Joe Stilwell who had led the retreat after trying to stop the Japanese in the fighting

from Rangoon to Mandalay.

Because they were fighting words, they appealed strongly to Americans. Because they were prophetic words, you

and your outfit have been given an extraordinary assignment. In the time which has elapsed since General Stilwell

and his men were run out of Burma, we have found out what caused our humiliation. Now we are engaged in retaking

the country, not solely for the purpose of occupying it and depriving the Japanese of its rich output of raw

materials, but to build it as a base which will give fresh support to China, and from which our forces can run

the Japanese out of Southeastern Asia and back to the crumbling shelter of their own islands.

That, in general, is your mission. There are two main roads toward its accomplishment. They are equally important

because they contribute to the same end. The first is to destroy, or make powerless, the enemies of your country.

The second is to win the friendship and confidence of all people who do not bear ill will toward us and who may be

ready to work or to strike a blow for our side. To win by friendly acts the esteem of those who have been

antagonistic toward us is equally to be desired.

The beginning of the cure for the misunderstandings which lead to war is an intelligently directed effort toward

an understanding of other people and of their problems and customs. This begets constructive good will and active

cooperation in the establishing of a better world. We Americans are among the best educated soldiers in the world.

Because the richness of our land has given us a greater opportunity than any other people on earth, we should

have greater kindness toward others and especial consideration for their rights and for their dignity. To be

deserving of what we have we should not parade our advantages but should accept them in humbleness of spirit.

It is the confident belief of the Army of the United States and of the people which it represents that you will make

these ideas a part of your faith and practice as a fighting American, and that you will apply them in your daily

experiences among the people of Burma as well as in your service together with other Allied soldiers serving in

this same theater. This soldier's guide book was prepared for that purpose. It is not a tourist's introduction

to Burma. Its object is not to entertain but to instruct so that you will be started on your way toward an

efficient service in the most important undertaking of your lifetime.

Because you were sent to Burma, you are more fortunate than a majority of your comrades in the Army of the United

States. In normal times - before the Japanese ravaged it - Burma was one of the most beautiful lands of the earth,

and although its palaces and temples have been cruelly used by the enemy and many of the homes despoiled, the

natural beauty of the land remains unimpaired. Too, the Burmese are a docile and normally hospitable people and

if you treat them fairly and learn to honor the simple rules which are important to their national and cultural

dignity, they will respond in a friendly spirit.

Finally, the country itself is not too difficult. Its climate is not extreme. There are periods of very heavy

rainfall and of excessive heat. But there is low humidity in the hottest seasons, and despite the heavy rains

of the monsoon, Central Burma is not sodden and fever-ridden. Consequently, the safeguarding of your health,

while necessitating extra precautions on your part, is not the extraordinarily difficult problem faced by

some of our forces in other tropical and near-tropical countries. That is so, even though the hills

surrounding

Central Burma are very malarious. If you observe the common-sense rules which will be discussed briefly in this

guide, and follow the more detailed instructions which will be given you by your company and medical officers,

you will continue to be marked "Duty" and will profit by your experience.

The wise soldier is one who talks little when in the company of strangers, but who acquires knowledge wherever

he can pick it up, knowing that anything he learns may some day be grist for his mill, and that what he learns

beyond the rudiments of soldiering during his military life will contribute to his success as a civilian.

These are important things for you to remember. They were not stuck in here merely as a twopenny sermon.

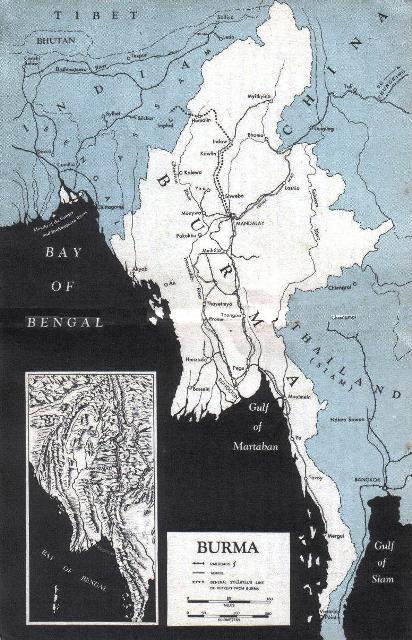

THE LAND OF BURMA

THIS land which a great poet once romantically and incorrectly described as a place where "there ain't no Ten

Commandments and a man can raise a thirst" is approximately the area of Texas, but with fewer wide-open spaces.

The means of transportation are generally quite primitive, and the lines of communication are relatively limited

except for the great watercourses which cut through Burma running north and south, and for the roadways paralleling

these watercourses. The roads and tracks running east and west through the country are inadequate and the distances

seem vast.

Were you to fly over it in a bomber, you would be impressed by how few were its cities and how much of its cultivated

lowland area was given over to rice fields. For the most part, it is an extremely rugged mountain country and its

ranges spreading from border to border are cut through by some of the largest rivers on earth, one draining down

from the snows of the Himalayas. Therefore much of the back country is quite inaccessible. It is frequented by the

quarry prized by the big game hunter, such as the leopard, the tiger, and the great buffalo called the "saing,"

which is reputed to be the fiercest animal on earth.

Burma lies between India on the west and China and Thailand on the east. It was out of this last-named country that

the Japanese invaded it in 1942, moving up from the narrow and attenuated "tail" of Burmese territory which flanks

lower Thailand. There was less than one division of British defending Burma at that time, supported by some Burmese

regiments and police forces. This small land army received sterling support from America's renowned "Flying Tigers"

who were then in China's service. Their resistance to the Japanese along the Salween River line, coupled with the

action of the British infantry, was one of the few bright spots in an otherwise cheerless period. But when the

Japanese got over the Salween, the fate of lower Burma was sealed and Rangoon had to be evacuated. The enemy had

won the keys to the country.

The fight was continued in upper Burma, and although the Japanese had already cut through the lower (railway) link

in the Burma Road, via which China received military supplies from Britain and the United States, the second stage

of the campaign developed around the effort to hold the railhead and the highway portion of the Burma Road. The

defensive operations were carried out along the valleys of Burma's two other great rivers - the Irrawaddy and

the Sittang.

Chinese regiments, lacking in artillery, ammunition, and everything but willingness to fight for the Allied cause,

came down from the north and joined with the British. The British could spare only meager forces from the other

theaters. We sent nothing but a stout-hearted commander and a few aviators because we were not ready.

Thus the campaign wore through to its inevitable conclusion. We took our "Hell of a beating" and the defending forces

did well to destroy the oil fields along the Irrawaddy - which, exclusive of the Middle East, are the major source

of petroleum on the Asiatic mainland - and to save a few tired remnants of the two defending groups which, despite

terrible losses, stayed game and retreated into the Indian state of Assam and the Chinese province of Yunnan.

This all too brief description of the geography of the campaign provides likewise an outline of the economic

geography of Burma. Mountains cover its frontiers to the west, north, and east, and to get over these ranges at any

point is a considerable task for an army. Most of the cultivated and arable parts of the country are in the

southern part of upper Burma where the great rivers wash down to the sea, forming great flats of land from the

soil eroded from distant mountain peaks.

The shape of the country might be compared to a cupped hand with the outside of the palm representing the coastal

plain. These great natural mountain barriers and the accessibility of the coast, coupled with the presence of

adequate harborage, give Burma unique military strength. The army which is strong enough to get into it at the

present time will be strong enough to hold it and to make a fortress of it from which to continue the offensive

against the enemy.

MEET THE PEOPLE

MOST of Burma's population live in the valleys of the Irrawaddy, Sittang, and Salween, and upon the fertile deltas.

They are a nonwarlike people, and under normal circumstances Americans can count upon their friendship. The record

shows, however, that a small percentage of them were willing to swallow the promises made by the Japanese, and

actively aided them at the time the country was invaded. There was a Fifth Column which pillaged the cities, harassed

the British rear, and made the retreat difficult, in marked contrast with the loyal action of the native military

forces.

You are given this reminder because of what it suggests as to your personal conduct. Though you are to be associated

with a friendly people they are not to be given your confidence. Many of them have had to deal with the enemy for an

extended period, and some of them have been active enemy agents. Therefore, a continuing vigilance is required of you.

While in service in the United States you heard much about the importance of security; in other words, the

safeguarding of military information. The application of the lessons then learned is now to be strictly applied.

Do not discuss military affairs with the people. Should they question you, act courteously, but either change the

subject or profess ignorance. When you are in the company of your comrades but away from camp, use the utmost

caution in speaking of anything pertaining to our forces, even if your

conversation is directed toward a friend

in the service. There is always the danger that you will be overheard. This is a bit of advice on a very large

subject. More specific instructions will be given you by your commander.

Precautions of this kind will not lose you the respect of the Burmese. In fact, the essence of getting along well

in a strange country is to mind one's business and let the other fellow enjoy that same privilege. To exercise

a lively curiosity about the manner of life in this strange country to which you have been ordered will not

offend the Burmese, provided that you act with restraint and courtesy and that you do not tell the permanent

residents what is wrong with their country. It is your privilege to tell them about your own country, or about

your family, or to discuss other such general topics. But it is your duty not to talk to them about the Army of

the United States or to engage in political discussions with them.

The words from an encyclopedia are as appropriate as any in describing the general characteristics of the Burmese.

"The women are more industrious and businesslike than the men but their school education has been neglected. The

Burmese women enjoy an amount of freedom unusual in non-European races. As a whole the Burmese are

characterized by

cleanliness, a sense of honor, and a love of sport, but addicted to a life of ease and laziness."

In sum, and not exclusive of the last point, those are qualities which are likely to appeal to an American, and

which convey a promise that your tour of duty in Burma will be attended by friendly relations with an interesting

and relatively progressive people. The unknown private in Kipling's poem, The Road to Mandalay, found them

so, and grew homesick for the land, even though he badly scrambled its geography, as you will discover if you ever

get to the Moulmein pagoda and try to look "eastward to the sea."

The women of Burma still smoke "whacking white cheerots" and the chewing of betel nuts is enough of a national

habit that you may at first be astonished by the number of Burmese with unsightly and badly discolored teeth

and gums. Despite this bad first appearance, you lasting impression will be one of a people who have reached a

relatively high order of living. The Burmese are Buddhists and their religion occupies a foremost part of their

life, and is one of the chief reasons for the picturesqueness of the country, every town and hamlet being marked

by its own pagoda, and generally by a monastery. The spiritual head of every village is the yellow-robed pongyi,

or monk.

Other fixtures of the average village in upper Burma are a large encircling fence for the purpose of keeping

out robbers and wild beasts, and the village school house. Even in the country districts, and except for the hill

tribes in the more remote mountain areas, the Burman men get at least a smattering of education. They use it to

good advantage and their religion is conducive to a generous attitude toward life. Also, many of the men spend

some part of their life in a monastery. The chief precept of the Buddhist is to do such good works on earth that

he will be prepared for the next reincarnation. The bestowal of alms, the giving of rice to priests, the founding

of a monastery, or the building of a rest house for travelers are all acts of high merit.

good advantage and their religion is conducive to a generous attitude toward life. Also, many of the men spend

some part of their life in a monastery. The chief precept of the Buddhist is to do such good works on earth that

he will be prepared for the next reincarnation. The bestowal of alms, the giving of rice to priests, the founding

of a monastery, or the building of a rest house for travelers are all acts of high merit.

These are things which the American can understand and respect even though he practices another religion.

Therefore you need hardly be counseled that in your life among the Burmese you will be ever mindful that a

considerate and dignified attitude toward all things pertaining to the religious life of the country is paramount,

and is the beginning of a good relationship between our Army and Burma's people. In their religion, you will

find much that is beautiful and little or nothing which seems by American standards either barbaric or unreasonable.

The hill peoples are not exclusively Buddhist. Although many of them are Animist (which is a term

pertaining to

primitive nature worship) Christianity has made much greater progress among the hill tribes than among the

Burmese. The most advanced of the tribes, for example the one known as the Sqaw Karens, are mainly Christian.

The Chins, on the other hand, are Buddhist. The outlook and mode of life of the tribes is usually high or low

according to the accessibility of the lands which they occupy. In the more remote mountains, the practice of

head hunting is still in favor. That may seem like the depth of savagery, but the world is certainly suffering from

worse evils.

The Burmans like color, life, and excitement. There is nothing about their religious practice which tends to humble

the person or subdue the spirit. Both sexes prefer to wear silks of bright but delicate shades, and even the poorest

possesses at least one silk "lungyi," which is the national dress, being a cylindrical skirt worn folded over in a

simple fold in the front and reaching to the ankles. Beside the lungyi, the men wear a rather somber short jacket.

The woman's upper garment, called an "aingyi," is similar, only it is sometimes double-breasted instead of single.

It is now quite general for Burmans to cut the hair as we cut ours. But where the old customs remain, the men wear

their straight black hair tied in a knot on one side of the head. The women dress their hair with coconut oil

and wear it coiled in a cylinder atop the head. The male head-dress is a "gaunbaung," which is a strip of vividly

colored silk worn wound round the head.

The picturesque people described in the preceding paragraphs comprise about two-thirds of Burma's total population

of approximately 15,000,000. Most of the remaining third is made up of two other Mongoloid tribes - the Karens

and the Shans - who resemble the Burmese but speak different languages and have their own dress and customs.

From the Karenni country come the celebrated "brass necked" Padaung women who are known to our

circus goers because

of the coils of wire which have stretched their necks to giraffe like proportions.

Immigrants from India, numbering about 1,000,000, are the most considerable outside bloc in the population. They

have moved into Burma during recent years. This tide reversed itself quite suddenly when the Japanese attacked

Burma. The Burmans have a strong national pride, embracing certain ideas about Burma for the Burmans. Especially

irritating had been the period when Burma was administered as a province of India. They had resented the presence

of the Indians because some of the latter had succeeded in money lending and middleman activities. When the

Japanese came like locusts, many of the Indians, beset on the one hand by Burmese hostility and on the other

by the threat of Japanese oppression, fled to the passes leading to their own country. The lot of those who could

not get away has probably been particularly difficult ever since.

Perhaps the brief account of Burma's people here given you errs greatly on the bright side. But your guide has

discussed them as they were before the great Japanese pestilence swept over the land - highly civilized, altogether

decent, reasonably progressive, and filled with the joy of living. The hard fate which came to them was not of

their making and certainly they merited better things.

Of what has happened since, this book cannot relate. There has been a great black-out over their land from the day

the Japanese moved in. States like Japan and forces like the Japanese Army have no compassion for defenseless

peoples no matter how deserving. There is every reason to believe that they have suffered greatly, that the gay

silks are faded and tattered, and that the song, the banter, and the laughter are gone from them, and that they

are not so prone now to deal with other people in an atmosphere of good will and hospitality.

But understanding what has happened to them, you will be prepared to take them as you find them. Burma is half

way around the world from the United States. You are probably going farther from your own home and your family

for the sake of your country than you have ever gone before. In those years when you had no direct personal reason

to consider how the speeding of communications and the tremendous changes in the nature of military power were

altering the basic considerations of our national defense, it probably never occurred to you that you might some

day soldier in Asia.

And it may seem to you now, when you consider it idly, that military service in Burma and along the road to

Mandalay has scarcely any connection with your duty to the United States. Yet East and West - the people of Burma

and the people of the United States - do meet on that common ground where men and women the earth over believe

that the true foundation of a true peace and of international order is common decency and fair play in the personal

and national life.

The people of Burma understood that as we ourselves understand it. They kept a neat and orderly house. Though they

had the same aspirations for independence as other progressive peoples, they usually sought this goal by

peaceful measures and by negotiation, rather than by recourse to arms. They have always used their land well, and

their dealings with one another have not been tainted by greed and exploitation. Materially as well, they have

contributed greatly to the advance of civilization.

The enemies of such a people should not be permitted to go unpunished so long as there are American soldiers

capable of dealing with these same enemies.

WHEN DO WE EAT?

BEFORE hearing anything of the Burmese diet, you would do well to consider your own. Every wastage of a pound

of food puts an unnecessary strain upon the United States where people - your people - already are being rationed.

To keep you supplied with food American ships are traveling a greater distance than to supply any other American

force. Therefore you should conserve food and encourage your comrades to do likewise. That is common sense.

The saving of food is as important a step in defeating the Axis as the killing of enemy soldiers.

Burma was once a land of plenty. Its staple food was rice, but the Burmese earth is fertile and the abounding

waters teem with fish. Hence a rice and vegetable diet served up in many forms with fish has always been the

usual table fare of the country. The Buddhist faith forbids the killing of animals and so exceptionally few of

the people are meat eaters. They like hot stuff - rice and fish and other dishes served with sauces that would

scorch an average palate. The fish is served either fried in peanut oil or made into a plate for flavoring

the rice.

This paste - called ngapi - is made of rotted, dried fish, and it has such universal use that most of the freight

depots have the characteristic and unpleasant smell of baled ngapi. They say that the taste is much better than

the smell and that non-Burmans may even acquire the same affection for ngapi as for ripe limburger cheese.

Burmans are generous and like to share their food - when they have it. As much a fixture as is white bread on an

American table are the rice flour cakes which are baked in small ovens in the earth, and are usually offered to

every visitor in a Burmese home. The guest at a Burmese meal can relax. He is not embarrassed by strange customs

and handcuffed by weird taboos. Good table manners there as in the United States can be epitomized in a few words:

"Receive naturally and praise warmly." Long accustomed to gracious living and to abundant food, the Burmans have

more recently been badly undernourished because of Japanese levies upon their food supply.

Peoples thus treated cannot return quickly to their traditionally hospitable ways. Hunger is the great modifier

of national habits. Therefore the American soldier will not expect that the Burmans will voluntarily share their

food with him, nor should he compete with them unnecessarily for their slender stores of merchandise.

It is part of our job to help them make their comeback. We can do that by helping them to conserve their food

rather than by taking it from them. To do otherwise would be pillage, putting us on the same level with the enemy.

There are few offenses which can be committed by a soldier that the military authority regards more gravely than

the plundering of the fields, orchards, or other food stores of a friendly country.

Give the Burmans this additional consideration: Never boast to them about the abundance or the quality of your

own food. If a man is hungry, he is in no temper for such conversation. If he is well fed, he is not likely to

be interested. If he is neither one nor the other, it is still bad manners.

THE WAY OF THE BURMESE

THESE people were once passionately fond of sport. They liked canoe races, bullock races, and pony races. They

boasted a national ball game called "chinlon" which was played by a small group of men trying to keep a light,

plaited caneball in the air for as long as possible - heeling it, elbowing it, kneeing it, kicking it, or

catching it with the head, but never handling it. The game required great skill and prolonged practice. The

Burmese also went in for clandestine cock-fighting - a taste many of our country boys will wholly understand -

and they bred an excellent strain of game rooster.

They are small people, not bruisers, and like most eastern folk, they fiercely resent being manhandled. Being

gentle by nature, they deserve gentle treatment at your hands. Yet the feeling for sport is so instinctive in them

that they supported a kind of boxing played with bare fists, but wherein most of the movements were akin to dance

steps, with victory going to the man who drew first blood.

Whether such recreation has temporarily disappeared from the national life because of the hardships imposed by the

Japanese, certainly it will thrive again through decent treatment and encouragement, and with the beginning of the

return to a normal kind of living.

Sport invariably influences the deeper current of a national character, and it has done so with these unassuming

people "somewhat east of Suez" with whom your lot is to be cast during the period immediately ahead. They have

the directness which we sometimes think in our conceit is strictly a trait of western civilization.

In their shops and markets, they do not like to haggle or bargain as much as the average Oriental. They will size

you up and name their price usually, and the choice is then yours - take it or leave it. They charge high prices,

but their merchandise is of good quality - when they have it. But we know that the Japanese have cleaned out the

bazaars. The country is now certain to be cluttered with Japanese-made goods, a point to be remembered in case you

have enough time away from duty to hunt for souvenirs. Nearly all soldiers do it, and for that reason, nearly all

merchants regard them as good prospects for a gold brick or a fur lined mess

kit.

Either at trade or when visited in their homes, the Burmans deal simply and with a lack of formality which

Americans welcome. Shaking hands isn't the general practice, though some Burmans with a western education are as

ready to exchange handclasps as any American.

When calling, it is proper for the guest to ask for the man of the house, but again it is pleasant to remark that

some slight social error in Burma will not provoke great wrath or dire retribution. The home atmosphere

is one

of general kindness, and it is said that no children in the world are better treated by their parents than the

children of Burma. One way to a Burman's heart is to speak with appreciation of his children; another way is to

match him in his respect for elderly people.

They set an example of cleanliness that is all too rare among peoples of the world and should turn many an American

face red. Every day is Saturday night for the average Burman, and either the village well or his back veranda

will serve as a place for the daily bath. Also, they have the same habits of modesty regarding exposing the body,

and of privacy in going to the rear that is supposed to obtain in the best of our western civilization. You won't

have to worry about Burmans committing a nuisance on your post.

What else is there to be said of their folk ways? Only that some critics complain that the Burmans think it polite

to tell you what you want to hear. If you ask, "Am I on the right road?" they smile and say, "Yes," no matter if it

is the wrong road. A most enlightening point. However, there are people scattered from Maine to California whose

minds work in this same delightful though puzzling fashion. They are not Burmans. In fact, they have never been

to Burma.

THE WAY OF A SOLDIER

THERE is one prime and lasting advantage in seeing the world as a soldier, as every old soldier will tell you. Only the soldier gets to the heart of the

matter. A country is reflected only in the character of its people and an average globetrotter moves much too fast

for reflection. But the alert soldier, on the other hand, must seek knowledge of the people first as a matter of

professional duty, because the correctness of his information about them is the key to getting along with the

country.

It is from seeing the people under varying conditions of work, recreation, discipline, danger, and excitement that

you will learn those things about Burma which will be of value to you later in life.

They occupy the foreground of your experience in Burma, and so your guide has pointed first to them. Beyond them is

the land itself, enriched by a romantic history, beautiful in its varied landscape of rugged mountains, great river

valleys, fertile coastal plains, and dense jungle, and ornamented by man with the kind of architecture which will

win delighted "ahs" and "ohs" from any group of tourists.

The cities of Burma, about which we have said little and of which we will say no more since you will discover them

for yourself, are as pleasant to the eye when the land is at peace as are any cities in the world. But it is not

alone in Rangoon, Mandalay, or Moulmein that one finds rare beauty in the things men have built. Go to the small

towns, meet the people and view their handiwork! We in America love our villages, if they happen to be home, but

when it comes to eye appeal, we don't do very well by them. The Burmans do better. They like to place their towns

on high hills and to situate their picturesque pagodas at the most prominent spot thereon. Neat people, they do

even the big things neatly.

From learning the WHAT and the WHERE of Burma's people at present you can turn to the WHY and HOW of their past. At

the present time you are making history and you haven't much time for the study of it. But the value of every

souvenir you collect in Burma will be enhanced later on by what you remember of the country from which it came, and

when you go sightseeing, as you are expected to do when duty permits, the experience will be twice worth while if

you understand what you see. The guide therefore includes just enough about history to give you a few reference

points.

In ancient times various Mongolian tribes migrated out of Tibet and Western China searching, as men of ancient times

invariably sought, for a better country. They found it in what is now called Burma. It was a country with little

or no true grassland but covered quite generally with amazing forests - great tangles of bamboo, vast stands of teak,

one of the most highly-prized woods known to man, and in the uplands, such familiar species (to ourselves) as pine,

spruce, oak, and rhododendron. It was well-populated forest, its denizens including many species of monkey, elephants,

the rhinoceros, tigers, leopards, the small barking deer, many kinds of tropical birds, including the parrot, and

an interesting assortment of snakes, including the python.

These creatures still inhabit the Burma forests. Soldiers may hunt the larger animals, though a license is required,

and most of the big game is protected by a "closed" season. As for parrots, never shoot them! Snare them, and then

teach them to sing "Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition."

Negroid tribes were there when the Mongol people arrived. They were killed or driven out to the last man, and the

remnant now survives in the Andaman Islands. Settling on the land, the Mongolian tribes began to destroy the

forests to make space for crops, and when the land became poor because of improper cultivation, they destroyed

more forest and took up new land. It was in this way that a considerable area of Burma became denuded.

Buddhism became the integrating and moving force in the life of Burma at just about the beginning of the Christian

era. Looking back over those 2,000 years, the Burmans have some right to claim that they have had perhaps the most

continuous orderly existence of any people on earth. What is known of the first millennium, however, is largely

legend and fable in which petty chieftains were given a build-up until they became great kings. Recognizable

history in Burma starts from about the time that William the Conqueror was downing Harold at the Battle of Hastings.

A king named Anawrahta came along and got all the boys together, founding the Pagan dynasty in A.D. 1054. He and

his 10 successors were the first real rulers of Burma.

The first Europeans to see Burma were the Portuguese. They didn't try to whip the Burmans; they joined them, the men

marrying Burmese women. That was about 100 years before we were staging the Boston Tea Party and getting ready for

the Revolution. In the following century the British East India Company established trading posts in Burma. That was

the age of great colonial expansion and the British Empire was growing at a phenomenal rate.

Still, Burma remained free and independent under the exclusive charge of its native kings until well into the

nineteenth century. The British having meanwhile come into India, friction between the two countries began to

develop along the western border and at last flared into the first Burmese War in 1824. The terms of the peace

gave certain territories to Britain but Burma continued under the rule of its native monarchs. At the same time

a British resident was placed at the Burmese court. There was one other small war between the two countries shortly

before our own Civil War but without radically affecting the relationship between them. Britain gained a little

more territory. The local government grew weaker. The tide had set. Historians make much of native misrule during

this period, citing large-scale atrocities instigated by the kings and a general failure to govern firmly and

deal with the needs of the people. However that may be, the end of Burma's political independence came on January

1, 1886, when the British deposed King Thebaw and his Queen, Supyalat, two sovereigns whose names have been warbled

by almost every baritone in America because Kipling put them in a song. Thebaw was quite an intriguer and he had

a bad habit of wiping out anyone who got in his hair. In those days the kings wore their hair very long. What

finished him, however, was a proclamation calling on his subjects to annihilate the English. A British expeditionary

force crossed the frontier and proceeded up the Irrawaddy. In one month the campaign was over.

Of the subsequent period under British rule, one authority remarks: "Perhaps never in the history of any country has

the contrast between its past and its present been so great and so rapid." The conditioning influences of an

impartial administration of justice, of improved communications and expanded commerce and the humanizing effect

of education and medical relief all contributed to Burma's forward surge. Too, as the Burmans profited by these

general advantages, their sense of unity and of nationhood became stronger, and by degrees they progressed in

self-government within the framework of the British Empire. Long ago Burmese women with property qualifications

were given the vote. Finally, partial autonomy was granted Burma in 1937, the last major milestone in the national

history to precede the arrival of the Japanese plague.

The love of liberty which is strong in these people is a feeling which any American soldier will respect and admire.

Under British administration they had progressed in the wise use of freedom in much the same way as the Philippines.

But when the dike broke in Malaya and the Japanese crossed the Salween, within the passage of one month the Burmans

were reduced to a state worse than slavery. That "Hell of a beating" fell heaviest on their sore backs.

What does it all mean? You may well have asked yourself that when you heard for the

first time that you were to do

duty in Burma. Perhaps the lesson is that in our time, to give other peoples a dream of freedom - simply by setting

the good example for them - is no longer enough. Ways must be found to help them and to insure that spoilers like

Japan and Germany are never again given the opportunity to cut them down in the very hour when they are learning

to stand erect.

That is our responsibility to ourselves. At the signing of our Declaration of Independence, a great American used

words to his fellow countrymen which apply today to all peoples who love freedom above all else. "We must all hang

together or assuredly we shall be hanged separately."

YOUR HEALTH, SOLDIER !

TO win the respect of such people as the Burmans is an aim worthy of a soldier. There is one way to do it - the

simplest way - by acting the part of a soldier. What that entails is well put by Private Hargrove when he comments

to other enlisted men "the spirit that gets you when you're on the regimental parade ground with the whole battalion

for retreat parade. Every mother's son there wants to look as much the soldier as the Old Man does."

And yet, the man who wears his uniform well but doesn't take care of his body is strictly a clothes-horse and not

a soldier. The sign of the man who is in tune with his regiment is that he does not take unnecessary chances with

his health. Such a soldier realizes that the illness of only a few men will cut deeply into the efficiency of the

whole organization. To him, alertness means, first of all, taking care of his body.

There is therefore no good purpose served by supplying you with a long list of red-light warnings such as: "Don't

get bitten by a snake!" or "Don't let mosquitoes use your back for a parade ground!" or "Don't cast an eye on a

native woman!" Under a given set of circumstances each of these experiences may prove, let us say, unavoidable.

The common sense thing to do is to consider, should they befall, then what's to be done? The Army of the United

States - through your company officers and your medical service - is prepared to give you the answers. That is one

of the duties of your superiors. Service in Burma imposes special health conditions and requires a wide knowledge

of local conditions.

It is true that Burma - due to the work of the British health service was at one time remarkably free of many of

the tropical diseases which are a problem to our forces elsewhere in the Pacific area. But Burma has been for long

in the hands of the enemy. The Japanese would have no scruples against polluting wells or contaminating food stores

in such way as to cripple our army. They will turn every weapon within their power against us and any land from

which they are compelled to withdraw is likely to be left in such condition that there is well-hidden menace at

every turn for the American soldier. You need to remain on guard.

There is, therefore, this general rule for your guidance: From the moment when you set foot in Burma, make a knowledge

of health conditions a part of your working equipment, and when you are in doubt, never hesitate to ask questions of

your superiors. An ambition to learn is the surest mark of an alerted soldier and is never lost on a competent

officer.

Then if you must take chances with your health, either because duty leads you in that direction, or because of your

personal needs, take all of the precautions which will cut risks to a minimum. Prophylaxis was installed by the

Army of the United States for the specific purpose of keeping soldiers out of real trouble. It is indecent only

when it is ignored and shameful only to the soldier who thinks he is too smart to have need of it. Venereal diseases

are always prevalent in tropical countries. They will be more so in a country whose women have been used by the

soldiers of the enemy in any way that they pleased. If you are going to be knocked out of the ring by the Japanese,

it would be better to get shot.

YOUR SPECIAL ORDERS

KIPLING'S British soldier never forgot Burma, and he lived his life through dreaming of the wind in the palm trees

and hearing the call of the temple bells. All that has been said in this short guide for American soldiers is by

way of suggesting that there is an attitude, which once attained by the American soldier, will not only serve the

present military purposes of his country, but will make his service in Burma a monument in his personal life and

recollection. The ideas can be summed up for your benefit in words paraphrasing a soldier's ten commandments. You

special orders are:

KIPLING'S British soldier never forgot Burma, and he lived his life through dreaming of the wind in the palm trees

and hearing the call of the temple bells. All that has been said in this short guide for American soldiers is by

way of suggesting that there is an attitude, which once attained by the American soldier, will not only serve the

present military purposes of his country, but will make his service in Burma a monument in his personal life and

recollection. The ideas can be summed up for your benefit in words paraphrasing a soldier's ten commandments. You

special orders are:

1. To take charge of your health as never before in your lifetime, realizing the greatness of the ends which your

country has in view.

2. To walk in Burma in a military manner, keeping always on the alert and respecting all rules and customs so as

not to offend those Burmans who are within sight or hearing.

3. To report at once to the nearest medical station if you have risked your health in such a way that you may

have endangered your personal force.

4. To repeat all special warnings about health precautions and treatment of the local population to all comrades

whose sense of duty may be more distant from the spirit of the regiment than your own.

5. To quit Burma only when the distress of that country is properly relieved.

6. To receive, obey, and pass on to your fellow soldiers the spirit of the undertaking in which you are engaged

so that all ranks will be stimulated to follow the line of duty only.

7. To talk to no Burman about your line of duty.

8. To do those things which will win confidence, and not spread alarm, in case of disorder.

9. To call upon your superiors for advice and instruction in any situation not covered by instructions.

10. To salute the courage and the good will of all forces and nations engaged with you and your country in the

present undertaking, to measure their worth according to their works and not

according to their color and to

refrain from judging others by our standards.

To rephrase the eleventh and final general order is not necessary. It tells you to be especially watchful at

night. This is a long night - one of the longest in world history. Years have passed since the Axis began to put

the lights out, first over Asia, then over Europe, and then all over the earth. Until men can again stand in

sunlight, there is no release from especial watchfulness for the American soldier.

This new dawn, too, will "come up like thunder" in Burma, but the thunder will be the echo of American guns. As

strange as is your new experience, it is not more difficult or dangerous than is the daily living of millions

of other American soldiers, marines, sailors, and merchant seamen serving in other lands and waters the world over.

It is our turn now. We took "one Hell of a beating." That first bad round was weathered. It is time to give it back.

CHECK LIST OF DO'S AND DON'TS

NEVER fool with a water buffalo. That animal is bad medicine and has no respect for the American uniform.

Soldiers are not expected to go around maltreating large trees, but some of the Burmans venerate these objects

and so a special warning is required on the point. Treat every Burmese tree as respectfully as if it were a

California Sequoia or Redwood.

Take off those issue shoes before entering any Burmese pagoda or other holy place. The Burmans require it. It's

like taking off your hat before entering an American church.

Work through the Thugyi, or village headman, when seeking permission to make camp, attend a festival, or take any

other action touching Burmese life. The Thugyi is what we would call "the works," and you can't go wrong by treating

him with deference.

Never touch anything in pagodas, temples, or shrines. Even their crumbling ruins should not be defiled by

removing anything from the premises or writing on the walls.

Try to speak to the Burman in his own language after you have picked up a few phrases, but if he doesn't understand

it, don't shout. That doesn't make it any clearer.

Burma is overrun with dogs. The Burmans don't take good care of them but they are resentful if anyone else

mistreats them. The barking of the dogs may disturb your sleep at night. Don't throw a shoe; you will need it.

Should you see Burmans and Indians engaging in a brawl, don't get into it, and be sure to give them elbow room.

As is the case back home, the worst things usually happen to the innocent bystander.

Should you attend Burmese festivals and Pwes (theatrical entertainments) keep everything under control and leave

the show to the participants. The 3 months from July to October are set aside by the Burmese as Wa, a sort of

Lent during which there is supposed to be no courting and marriage, and which is terminated by a great festival

of lights called Thadingyut. It is a real jubilee period.

Another such is the Buddhist New Year which comes in April and which is celebrated by Burmans throwing water over

one another as we do confetti. It may be less fun but it's easier to clean up on the day after. The Burmese fetes,

despite all of the enthusiasm, have a religious significance; therefore the soldier should regard them with restraint.

Before attempting to photograph any citizen of any country, it is best to approach him respectfully and ask his

permission. By so doing, you will usually win his cooperation.

MISCELLANEOUS INFORMATION

Currency

THE currency used in Burma is the same as that in India:

1 rupee = 16 annas

1 anna = 12 pie or 4 pice

The rupee is a silver coin worth about 30 cents in American money. The anna, pie, and pice are all bronze coins

having approximate values of 2 cents, 1/6 cent, and 1/2 cent in American money.

The Japanese have probably introduced some of their own money, but the paper put out by the Axis occupation forces

is likely to be worthless.

Weights and Measures

Weights and Measures

1 lan (4 toung) = 88 inches

1 tain = 1,069 yards (slightly over 6/10 of a mile)

1 dain (4 tain) = 2.43 miles

1 sah = 1 gallon

1 viss or paiktha = 3.6 pounds

Telling Time

The same calendar as ours is used, or at least widely known, in Burma. The difference in standard time between

New York and Burma is 12½ hours, and the date, because Burma is west of the International Date Line,

is one day ahead of New York. At high noon Sunday in New York, therefore it is 12:30 a.m. Monday in Burma;

and at 8:30 Sunday morning in Rangoon, it is just 8 o'clock Saturday evening on Broadway.

Sanitary Conditions

Tropical diseases are present in Burma, but you can avoid them by following a few simple health rules.

The three most common "fever" diseases are malaria, dengue (pronounced "deng-gay"), and a

sand fly fever.

The first two are spread by certain species of mosquitoes, the last by a tiny

sand fly. The surest way to avoid these

diseases is to keep from being bitten. Sleep under a mosquito net and keep your arms and legs covered at dusk.

Two other diseases, relapsing fever and typhus, are spread by lice. Give yourself a frequent once-over to get

rid of any such visitors. Fleas can spread bubonic plague by biting diseased rats and then biting humans. The

plague flea cannot survive sunlight.

Food and water are often contaminated with cholera or dysentery. Diarrhea is the main symptom of both diseases.

Do not eat raw fruits or vegetables unless they have been peeled or washed in disinfectant. Drink only boiled

or chemically purified water, unless your sanitary officer okays the water supply. Tea is a refreshing beverage

in hot weather, but make sure that only pure water is added in cooling it.

A common disease of the eye, called trachoma, is spread by contact. It can be picked up by using the towel of

an infected person.

|