| 75th Fighter Squadron pilot Lt. James M. Taylor was forced to bail-out when his engine failed during a dog-fight with Japanese fighters over Hengyang, China. He was captured by the Japanese and was a Prisoner of War for 10 months and one of . . . |

By James M. Taylor

Our warning network told us there were Jap planes in the area. Operations decided to send up 15 fighters to look for them. It was a cold, crisp morning. The sky was bright, bright blue. Perfect for hunting.

My plane had been on a night mission and still had the drop tanks on it when I got down to the flight line. That was going to make it questionable as to whether it could be prepared for flight in time to make the mission. I wanted to go on this one, and was depressed that I might not make it.

"They won't let me go, with those drop tanks still hanging on the ship," I told my crew chief.

"If you pump the gas out of them, they'll let you go."

"Just show me the bolt that holds it on and gimmie a wrench!"

Lopez led the 15 of us on a sweep to Lingling. Jap planes weren't anywhere around so we split up and went in different directions. Lopez took seven planes south to Kweilin. Kelly took the rest north.

When we got in sight of the field at Hengyang, they were waiting. Some were on the ground, some were taking off and coming up to fight, and a lot of others were already in the air and coming at us.

Kelly got on the radio and called Lopez: "We found 'em. They're at Hengyang. Come on up here!"

My flight peeled off and dove on the field, firing. I went down with Gadberry, Griswold and Kelly. The rest stayed up and gave us top cover.

There were so many targets. You blasted one and when it flashed out of your sights, you looked around and picked up another. You strafed anything on the ground that came into your sights.

Mostly, I fired short bursts. More than three of four seconds heated up the gun barrels and burned out the lands. Then you had no control over where the bullets went.

Ground positions were shooting at me from bunkers up and down the field. I turned on them. There was a whole lot of radio yak going on, people yelling, a lot of it unintelligible.

As I came down on a shallow strafing pass, around 50 feet above the runway, my engine quit on me. It just died, like I ran out of gas all at once. No coughing, no warning of any kind. Just silence.

I was still doing about 450 from the momentum of my dive, but with that large, wind-milling prop acting for all the world like a giant air brake, that wouldn't last long. I pulled up into a chandelle and switched gasoline tanks. No reaction from my engine. My eyes flashed across the instrument panel in an instant. All my engine gages were redlined. It wasn't a temporary fuel loss. Whatever it was, it was far worse than that. My engine was not going to restart.

I was dead in the air.

I knew I had to leave my plane, so I pulled the canopy release. It didn't release all the way. Now the jam I was in got worse.

I rolled out of the top of my chandelle at 1200 feet, much lower than I'd have gotten except for my air-brake prop. My instant plan was to set up a glide and stay with the ship as long as possible so I could get away from the scene, then bail out. But now I was in double jeopardy. My prop slowed me down which made me a sitting duck for the ground ack-ack gunners.

Explosive cannon shells hit right on my cowling. I felt three whacks on my plane: BOOM, BOOM, BOOM. There were the three accompanying puffs of black smoke. Quickly, I dumped my nose and gave up 300 feet of altitude to try and pick up a little speed and get out of the gunners' range.

Now I was down to about 850 feet and I knew I had only a few seconds left to get out of the plane safely. The canopy was still hung, so I gave it a good lick with my elbow, and it fell free over the side.

Someone once told me that if you roll your trim tab all the way forward and hold the stick back against it to maintain level flight, then when you were ready to get out, all you needed to do was turn loose of the stick and the trim tab would suddenly dip the plane down and that would pop you right out of the cockpit. I tried that but, at my slow speed, there was no "pop." Now I was really scrambling to get out of that plane any way I could.

I went out, still in a sitting position, and only about 400 feet above the ground. The tail of the plane eased right by me, going about the same speed I was. I could have reached out and touched it. I pulled the D ring on my parachute and sat there, looking at the ring in my right hand. Then I felt a big jolt. I looked up and saw nothing but white over my head.

"It worked!" I said, aloud, with much relief.

It was my first jump. They never gave us any practice at it. I looked down and saw that my plane had pancaked onto the ground and had started to burn, sending up a dark, oily column of smoke.

I said aloud, "I'm coming down right in that fire."

It was kinda close. I landed right alongside of it. My parachute canopy drifted into the fire and burned. The Japs were so close I didn't have time to get my special escape kit out of the back of the chute harness. I just yanked the entire harness off, threw it into the fire, and my helmet after it, then started running.

They always had told me, "If you go down, head for the hills." That's where I started going. But I didn't get far. I saw a dozen Jap soldiers coming over the top of the next ridge, rifles ready, and bayonets fixed. They were spread out, making a sweep of the field where I was. I noticed a little shack off to my left. There were no tall weeds or bushes or anything to hide in or behind.

I hit the dirt. Flat. The soldiers kept coming. The closer they got, the flatter I got. I was like a snake stretched out in the shallow grass. They looked right over me, and started shooting at the little shack, pouring bullets into it. They thought I was inside, hiding. When they were now no more than ten feet from me, and still coming, I knew they were going to step on me.

I jumped up in their face. It scared them nearly as much as it scared me.

I held my hands up. When they got their wits about them they surrounded me and started shouting commands in Japanese. They took my gun, my watch, my Air Corps ring, and a small cameo ring my sister had given me for Christmas, a part of a pack of cigarettes, and a box of Red Top matches.

The matches were what really fascinated them. The Japs had little thin matches, like flat toothpicks. To strike them, they had to hold three of them together so they wouldn't break. Then they had to find a place on their match box that had enough phosphorous left so they could get a fire. My matches were all square and they lit the first time you struck them. The Japs really loved those Red Tops.

I heard a roar overhead and looked up. Lopez and his eight ships had arrived, and they joined the air battle.

After the war, I learned what had happened to the rest of the flight. Weldon B. Riley got lost. He bailed out about 80 miles north of Chihkiang, but managed to get to that base safely. Andrew Jackson Gadberry was wounded and bailed out near Hengyang. He later got back to the squadron okay. Robert P. Miller was killed. Nobody knew what had happened to me. Eventually I was put on the list of men Missing in Action.

The official record of the mission said: "Taylor stayed with Kelly until near the end when Kelly warned Taylor of Japs above and he pulled out but he missed Taylor who was not seen again."

About two months later, my folks received a letter from my old buddy from cadet days, Hugh D. Wilson. This is what Hugh wrote:

|

Dear Mr. and Mrs. Taylor:

I just received word of Buddy's death which was a big shock to me. I know he was a great loss to you, too, for he was fond of his family. He spoke of you so often and intimately that he made me feel that I knew you well. I have missed him a great deal in the past 10 months that we have been separated. I have been trying to join his squadron for a good while but was never able to do so. I hope it will give you some comfort to know that he was killed in actual combat rather than on a training mission as so many of our boys are lost. I understand he had a grand record up until that time, of which I know you are proud. I was so pleased to get your Christmas card. Please, know that I am sharing your sorrow a great deal. Sincerely, Hugh |

But of course, I wasn't dead. I was in a small group of captured Air Force men separated from all other prisoners and taken back to Japanese homeland. We called ourselves the Diddled Dozen.

The Diddled Dozen:

Front row left to right: 1st Lt. Freland K. Mathews, 1st Lt. James Wall , 1st Lt. Vern D. Shaefer, Donald Quigley, 2nd Lt. James Thomas, Capt. Don Burch.

Back Row left to right: 2 Lt Sam McMillan, Lt. James Taylor 1st Lt. Harry Klota, Howard, 1st Lt.Walter A. Ferris, 2nd Lt Sam Chambliss

The Diddled Dozen:

Front row left to right: 1st Lt. Freland K. Mathews, 1st Lt. James Wall , 1st Lt. Vern D. Shaefer, Donald Quigley, 2nd Lt. James Thomas, Capt. Don Burch.

Back Row left to right: 2 Lt Sam McMillan, Lt. James Taylor 1st Lt. Harry Klota, Howard, 1st Lt.Walter A. Ferris, 2nd Lt Sam Chambliss

|

Quigley, CO of the 75th, and Watts, who was accidentally dragged out of his plane while dropping cargo to the Chinese Army, had been held in Hankow under guard but not in jail. Oddly enough, both came from Marion, Ohio.

Meeham, Burch, Thomas and I also had been held in solitary confinement in Hankow in a kind of half-basement of a building used as a prison. We were filthy, lousy, unshaven, and unwashed since we had been captured. On 28 December 1944 we were taken to the Yangtze River boat dock where we were met by Quigley and Watts, neat and clean and well groomed, and put aboard a river boat bound for Nanking. At Nanking we boarded a train for Shanghais where we rode a truck on to a POW camp near Kiangwan Air Base.

|

The camp held about 1,200 men, including Marines and civilians captured on Wake Island and some of the North China Embassy guard. There was also an Italian crew of a boat scuttled in the Yangtze River being held there.

In our group were Air Corps men captured in China between July 1944 and April 1945.

On 31 December 1944 the six of us were placed in an end room of an empty barracks at the POW camp. Carlton, Lankford and Rieger from a B-29 crew joined us. They had come in the day before from Hankow where they had been held. The Japs forbade us to talk to anyone else in the camp but we could unload on each other all we wanted to.

After being cooped up in solitary confinement, I had lots to say.

Matthews, Schaefer and Ferris joined us on 18 February 1945. That made 12 of us - the Diddled Dozen - and on 15 April, Howard and McMillan came in. The entire camp began a move on 9 May that would take two months to complete, with our final destination being Japan itself.

After five days of riding boxcars we arrived near Peking where they put us in two warehouses. We slept on the concrete floors.

Chambliss joined us 23 May, with Wall and Klota on 6 June.

The Japs loaded us back onto boxcars on 19 June and we headed up the tracks into Korea. We got to Pusan and, after five days there, we were crowded into the hold of a waiting ship.

We made a very dangerous crossing of the Strait of Korea which took a day and a half, and landed at the southern tip of Honshu Island on 30 June.

The next day we boarded another train and headed over to the Pacific coast. At Aomori, the five enlisted men of our group were taken away, as were the civilians and a navy doctor, William Foley. We protested strongly but it did no good. The five spent the rest of their time in Japan working in a surface iron mine.

The rest of us were put on a ferry at Aomori for Hokkaido where we boarded another train and went north for several hours to some little place where we spent the remainder of the night. At noon, the next day, they called out all prisoners who were pilots. They put us on another train and we headed back south again to Sapporo where we were taken to a large frame building and kept under guard for the remainder of the war.

We had hoped to be in a prisoner of war camp but they kept us separated from the other military and confined us to one large room in a frame building on a small Japanese Army base at Sapporo.

There the Diddled Dozen remained until we were returned to United States military control on 11 September 1945.

The Diddled Dozen

By James M. Taylor

Shared by Terry Schwartz

Adapted by Carl. W. Weidenburner.

Read more about Lt. Taylor at PRAYED SANG CUSSED

More History at THE CBI THEATER

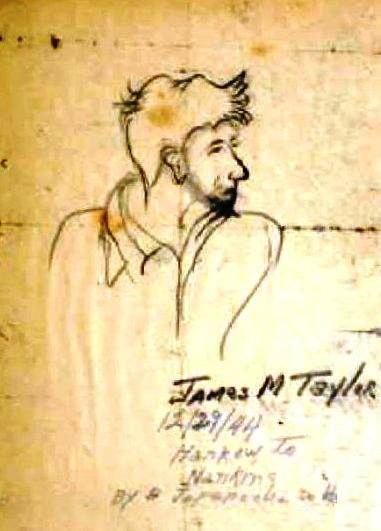

James Taylor's most prized piece of World War II memorabilia.

A drawing of him made by a Japanese guard while enroute Shanghai, China.

Note the beard and hair after two months in solitary confinenment.

James Taylor's most prized piece of World War II memorabilia.

A drawing of him made by a Japanese guard while enroute Shanghai, China.

Note the beard and hair after two months in solitary confinenment.