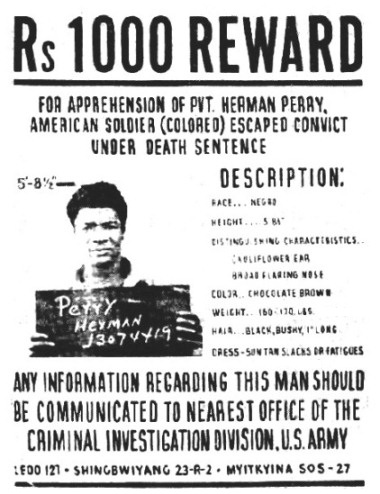

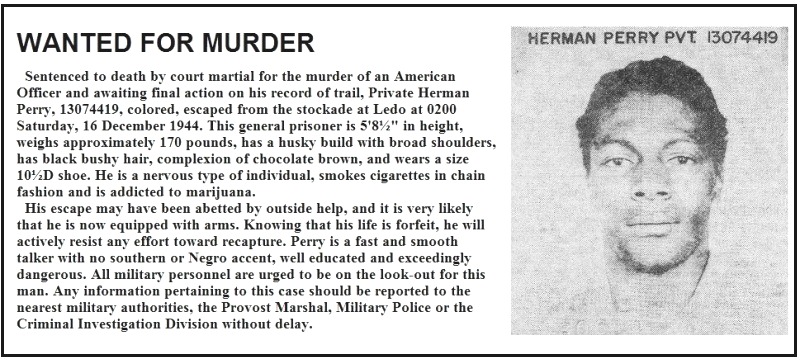

U.S. Army posted notice offering reward equivalent to $300

U.S. Army posted notice offering reward equivalent to $300 for apprehension of escaped prisoner Pvt. Herman Perry. |

The Story of Pvt. Herman Perry

During World War II, the U.S. Army executed 141 soldiers, most for rape and/or murder. Only one of these executions occurred in the China-Burma-India Theater. It was the culmination of what has been called "the greatest manhunt of World War II."

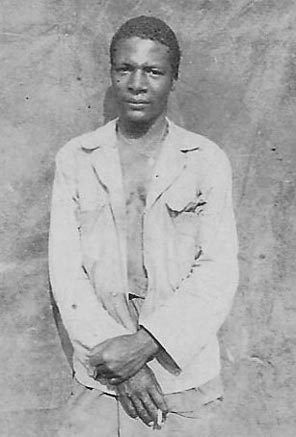

The subject of the manhunt, Pvt. Herman Perry was a member of the 849th Engineer Aviation Battalion, a "Negro" or "Colored" unit which consisted of African-American soldiers commanded by white officers. The 849th was one of the units sent to India to build the Ledo Road, a planned alternative route for supplies to China after Japanese occupation of Burma had cut the previous route for supplies, the Burma Road.

In March of 1944 the 849th was working on the road near Tagap Ga, Burma, operating rock crushers. The gravel from the crushers was used to surface the road, making it better able to standup to traffic and the monsoon rains.

Working on the Ledo Road was difficult to say the least. The route went through the mountainous terrain of Assam and the jungle of north Burma. Every ill of the jungle was present - dangerous wild animals, leeches, mosquitoes, malaria and dysentery - to name a few. The monsoon rains and oppressive heat made matters all the worse. The perceived importance of the road called for long work days, sometimes 16 hours. All combined to make construction of the Ledo Road "the toughest job ever given to U.S. Army Engineers in wartime."

Segregation and discrimination in the Army were prevalent in World War II. Discipline and punishment were harsher in African-American units and they almost always received the jobs nobody wanted to do. Thus, the 849th was sent to India and the Ledo Road project.

Opium and ganja (marijuana) offered brief relief from the rigors of work and escape from the boredom in the isolated jungle. Both were grown locally and readily available, and engineers like Herman Perry often passed the time this way, sometimes even while working. One evening Perry wandered into the woods and spent the night high on opium and ganja. He returned to camp on March 3, just before reveille, and slept through it at 0600. When he failed to report to work, the company's commander ordered him arrested for being AWOL.

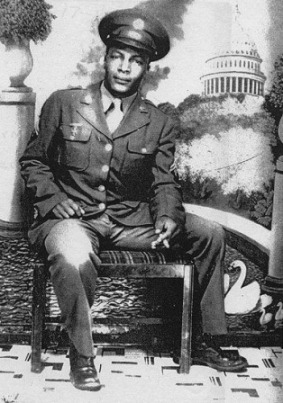

prior to departing for India. |

Having already spent time in the Ledo Stockade, Perry had no intention of going back. Beat down by his experiences in the Army, the conditions along the road, his previous harsh treatment in the stockade, and now under the influence of drugs, he had had enough. He refused to cooperate with those tasked with arresting him and taking him to the guardhouse. Unable to take him into custody, they had also failed to disarm him. He was still in possession of his loaded M1 rifle as he fled.

Some had suggested Perry speak to the battalion's commanding officer, Lt. Col. Wright Hiatt, with whom he had already spoken to once before. Maybe he was headed that way but he never made it. He hitchhiked a ride in a truck he encountered along the road, a common practice. The driver noted he appeared anxious, nervously handling the rifle he carried, a not-so-common practice while not at work.

Meanwhile, Lt. Harold Cady was enroute down the road with three soldiers in a jeep to check on repairs to a disabled bulldozer. Known as a hard-ass, strict disciplinarian in the 849th, Cady knew Perry from previous experience and was aware of the arrest order. As the jeep came upon and passed the truck, Cady recognized Perry in the passenger seat. He ordered the truck to pull over and both vehicles stopped.

Perry got out of the truck, holding the rifle. Cady headed unarmed toward Perry, who cautioned "Get Back!" Perry repeated his warning and the lieutenant stopped briefly, then continued to approach Perry. "Lieutenant, don't come up on me!" Lt. Cady continued. Now pointing the rifle at Cady's chest, the trembling, sobbing Private screamed the warning a second time, "Lieutenant, don't come up on me!" Cady crouched down just feet from Perry, putting his hands on either side of the rifle barrel as if to disarm him.

Herman Perry pulled the trigger, firing two shots in quick succession at point-blank range. The first bullet went through Cady's heart and pierced his spinal column. The second hit him in the stomach. He collapsed, falling forward, mortally wounded. Perry fled down the road. The three soldiers who had been riding with Cady quickly got him in the jeep and headed for the field hospital. He took his last gasp in the jeep and was dead on arrival at the hospital.

After firing, Perry ran down the road and dropped the rifle. He then fled through the woods and into the jungle beyond, where he wandered for days. The jungle only served to cloud his mind further, to the point where he wasn't even sure what he had done. He knew what he had done was bad, but rationalized it could be explained to the colonel. He made his way back to the 849th.

He walked into camp, making his way right down the row of tents that served as quarters for the men. Some of his fellow soldiers recognized him and quickly got him under cover in one of the tents. There they brought him back to reality. There would be no explaining, he had shot a white officer. All that awaited him was the stockade, a court-martial and the ultimate penalty.

|

Herman Perry was not the only man to lose it among the men of the 849th, not even the only one to shoot someone. They all suffered the same harsh treatment, discrimination and brutal punishments. Many had thoughts of doing just what Perry had done, or at least of taking some kind of action against those responsible for their plight. They were sympathetic to his current situation and helped him, rather than turn him in. Still, they couldn't hide him for long so he once again headed for the jungle.

His wandering brought him to a Naga village in the Patkai hills about six miles from the road. The Naga were headhunters who believed the taking of a head a symbol of courage. There was nothing more glorious for a Naga than victory in battle by bringing home the severed head of an enemy. Most of their battles were with other tribes in the area. British efforts and the introduction of Christianity had somewhat quelled their lust for heads, although it was still practiced from time to time.

The Naga considered the tall black American GI as somewhat of a curiosity. Perry was able to get in their good graces by sharing the rations he carried and allowing the Naga to use his rifle for hunting. The charm that had made him popular with the ladies back home in Washington, D.C. also worked with the Naga. They especially found the metal ration tins a precious gift, useful for making the trinkets they wore.

When rations ran low, Perry would sneak back down to the road, receiving the help of sympathetic members of the 849th. He was able to obtain cases of rations and other supplies which further ingratiated him with the Naga. The village Ang (chief) thought so well of Perry that he offered his daughter in marriage. They were married and given their own basha (thatched-roof hut) where they soon conceived a child.

Perry enjoyed his status in the tribe and the simple lifestyle of opium, ganja, farming and hunting. Among the Naga he was an equal, no prejudice or its associated harsh treatment as in the Army. He thought he might live-out the rest of his life here. Homesickness, however, soon set in. He wondered about his family back home but had no way of contacting them. He also longed for things American, especially cigarettes.

A tribesman was sent to a nearby bazaar (market) to obtain American cigarettes available on the black market. While there the man told others of a black American soldier living with his tribe. Word quickly spread, reaching the local authorities, the British and finally the U.S. Army. A trusted Naga scout was sent to confirm the story. On his return he reported there indeed was a black American soldier living in the village of Tgum Ga. Shown a picture, he confirmed it was Herman Perry.

MPs of the 502nd Military Police Battalion were sent to arrest Perry. On July 20, after traveling much of the night to reach the village, the scout again confirmed Perry was there. Four MPs made their way to the basha, finally crawling to avoid detection. Two approached the front of the hut while two covered the back. A barking dog alerted Perry and after seeing the two prone soldiers he bolted out the back, passing the two MPs, who fired at the fleeing man. One MP believed he had hit Perry in the chest, yet the wanted man was nowhere to be found and there was no visible sign of blood. Searching behind the basha they found a trail of broken branches in the jungle and followed it to a small stream. There they found Perry, indeed shot in the chest.

|

Much effort was put into bringing Herman Perry out of the jungle to a nearby evacuation hospital. Despite his serious injury he survived and as his condition improved he was moved to the 20th General Hospital. While at the hospital and under the influence of morphine and other pain killers, he was questioned by the Criminal Investigation Division. His answers amounted to a confession, which he was forced to sign and which would eventually help seal his fate.

The court-martial took place on September 4, 1944. In addition to murder, Perry was also charged with desertion (also punishable by death) and several counts of willful disobedience. The latter charges were based on his refusal to be arrested and his flight into the jungle. Perry's Army lawyer failed to discredit what amounted to a forced confession. He also failed to show that the shooting was not premeditated or that Perry had remained in the area and had not deserted. The prosecution relied heavily on Perry's signed confession.

The court-martial was basically a formality. It took just six and a half hours, including lunch and two breaks. After only a few minutes of deliberation, six white officers convicted Perry on all but the lesser charges. Herman Perry was sentenced to be dishonorably discharged, forfeit all pay and allowances, and to be hanged by the neck until dead.

More formalities followed. The conviction could be appealed, had to be reviewed by the Judge Advocate General in Delhi and Washington and had to be approved by theater commanders. Complicating matters was the recall of General Stilwell and the splitting of the CBI Theater into two. These formalities dragged on while Perry awaited execution in the Ledo Stockade.

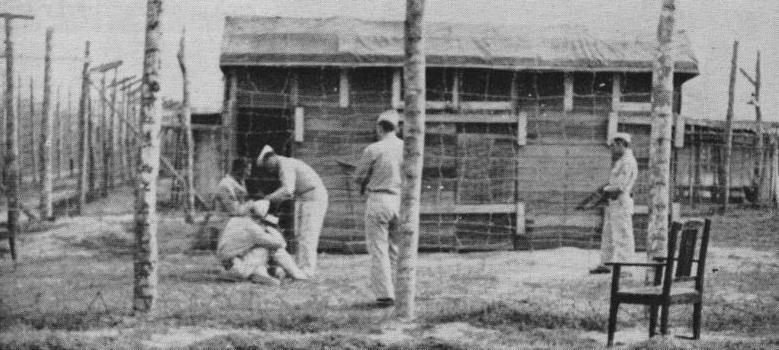

Longing for the freedom of his adopted home and comfort of his new bride, Perry planned an escape. The Ledo Stockade was not the most secure by any means. Guards bored by the dull routine rarely checked prisoners or visitors for contraband. Perry studied their routines and was able to obtain a pair of wire cutters from a sympathetic visitor. After three months, he cut his way through the wire fence shortly after midnight, December 16. He was once again free.

Now, "the greatest manhunt of World War II" began in earnest.

Heads rolled as those responsible for the stockade were disciplined, demoted, or transferred.

Reward posters went up all along the road.

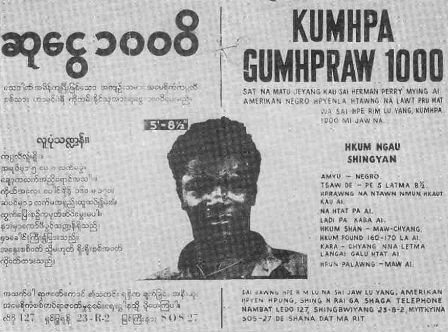

Fliers in Kachin and Burmese were distributed to native workers and air-dropped over remote villages.

Details of the escaped convicted murderer, complete with a recent photograph, were published in the theater newspaper CBI Roundup.

|

Perry was free, but had no food or weapon and was more than 80 miles from his adopted Naga village. He found his way to an abandoned timber camp, about five miles from Ledo. Word soon reached MPs back in Ledo that a black American had been spotted at the camp.

The MPs reached the timber camp just as the New Year 1945 arrived. They planned to sneak up and surround Perry, then order him to surrender, but their movements awakened him. He instead surprised them with a quick dash for the woods. They fired on him, emptying their rifles, but he managed to escape. Perry had once again eluded capture, but soon found he was also wounded again. This time he was lucky, just grazed by a bullet on his left foot. It would be weeks before anyone saw him again.

and air-dropped by the Army over remote villages. |

Meanwhile, all along the road the subject was Herman Perry. Tips about his whereabouts were received from Calcutta to Kunming. All proved false. Stories about his fate circulated among the men along the Ledo Road. Many believed he had escaped to the north, never to be seen again. Local newspapers dubbed him the "Jungle King" and the legend grew. The only fact however, was that he had eluded capture by the Army and was nowhere to be found.

Then on February 11 he showed up at the busy black market in Makum Junction. Brandishing a .45 pistol, he robbed two black soldiers of 95 rupees, then forced the store owner to make him dinner. While eating he disclosed a plan to the two black soldiers he believed he could trust. He wanted them to bring a truck, stocked with supplies, back to Makum.

Afraid of being shot, they agreed to Perry's plan. The two weighed their options on the way back to camp. They were sympathetic to their fellow soldier, but had no desire to spend time in jail for aiding an escaped convict. They flagged down an MP patrol and were brought to headquarters of the 159th Military Battalion at Chabua.

Major Earl O. Cullum, commanding officer of the 159th and Provost Marshal of Chabua, listened as the soldiers related Perry's demands. He devised a plan to capture Perry, enlisting the help of the two soldiers Perry had threatened. They would deliver the truck to Perry as agreed, but then follow Cullum's capture plan. There was also a backup plan, just in case.

Both plans failed. On the evening of February 20, Perry again fled into the woods in a hail of bullets. Cullum was slightly wounded in the leg by friendly fire. Perry was hit three times. His hip and left foot were again grazed, but his right foot was bleeding badly from a bullet wound. He made his way to the edge of a rice paddy where he rested, hoping the pain in his foot would subside enough for him to continue.

Having fallen asleep, he was soon awakened by the sound of barking dogs. MPs with German shepherds were tracking him. The dogs would soon find him for sure. Having no choice, he ran again, ignoring the pain in his foot.

An MP took aim at Perry's head and fired on the fugitive as he ran. Perry felt the bullet whiz past his face. As he reached the relative safety of the woods, he realized he'd been hit again. The bullet had pierced the skin of his nose just between the nostrils. He had, however, unbelievable to the MPs, once again eluded capture.

While Perry was presumably making his way back to Tgum Ga, his young wife gave birth to a son. A team searching for a downed plane would later confirm this in August, seeing the curly-haired, dark skinned infant along with cases and cases of Army rations stored in a basha papered with the wanted fliers air-dropped by the Army. It would be the only time Perry's son would be seen.

Having been admonished by his commanding officer for failing to capture Perry, Major Cullum now made it his top priority. In doing so he became a major player in the Herman Perry story and would be forever linked to it. His first-hand knowledge and penchant for storytelling would later lead him to become somewhat of a Perry historian and author.

Leads took too long to reach the MPs at the 159th and were then cold by the time they were investigated. Cullum decided to take the hunt for Perry mobile, hoping to be closer if he was spotted. He and a hand-picked team of MPs set out on what would become an eighteen day hunt through the jungle for the fugitive.

The consensus was that Perry would try to make his way back to his adopted village of Tgum Ga. There was evidence, however, that he may be moving south toward the railroad at Namrup. Cullum and his team arrived at Namrup on March 9, stopping at the office of an Army railroad maintenance unit. While there, news came from local farmers that Perry had been seen sleeping in a nearby basha.

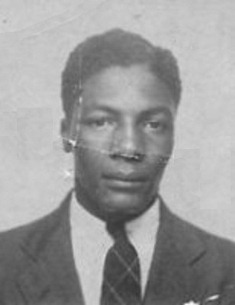

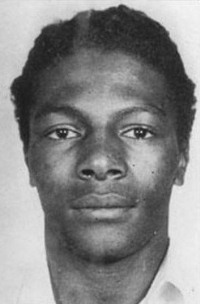

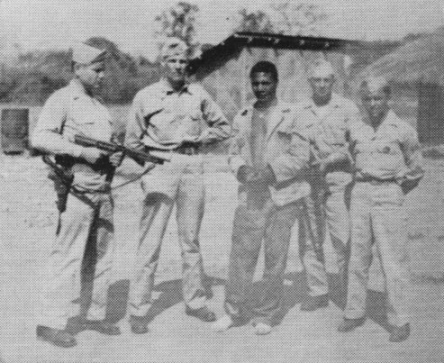

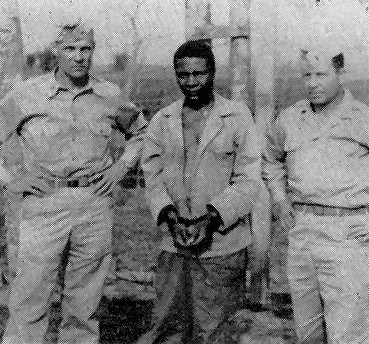

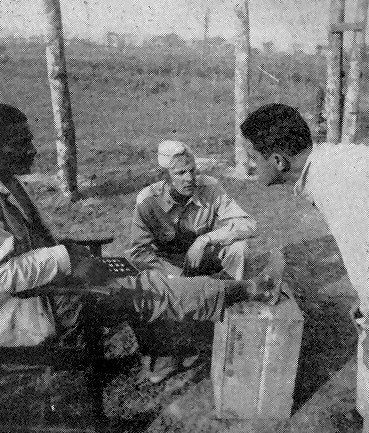

The hunters and the hunted.

Pvt. George Crosby, Maj. Earl Cullum, Pvt. Herman Perry, Sgt. Earl Gainor and Cpl. Bernard Black.

The hunters and the hunted.

Pvt. George Crosby, Maj. Earl Cullum, Pvt. Herman Perry, Sgt. Earl Gainor and Cpl. Bernard Black.

|

Cullum and three of his most trusted MPs, Sgt. Earl Gainor, Cpl. Bernard Black, and Pvt. George Crosby, along with three local officials, headed out in jeeps for the reported location. They drove three miles then hiked another two before reaching the shallow Disang River. Across the river lay the basha where Perry had been reported sleeping.

Not wanting to repeat past failures, where MPs had failed to fire or fired blindly into the jungle, Cullum decided that only he and Pvt. Crosby would approach the basha. Guided by one of the locals, they crossed the river and reached the basha.

There were three natives warming themselves around a fire to the side of the basha. Crosby covered them with his Tommy gun as Cullum checked the basha. It was empty. Now Cullum focused on the natives around the fire. Something appeared not quite right.

Cullum approached the three men around the fire, instinctively grabbing one by the wrist as the others fled into the woods. An American voice said, "You got me." It was Herman Perry. The manhunt was over.

Back at Namrup, Cullum wired the news to Delhi:

| CONDEMMED ESCAPEE MURDERER HERMAN PERRY CAPTURED 2000 HOURS NINE MARCH NEAR NAMRUP BY CULLUM AND 159 MP BATTALION SEARCH TEAM. NO GUNFIRE AND NO INJURIES. KILLER APPEARS IN GOOD CONDITION. BEING TAKEN TO 234 GENERAL HOSPITAL FOR EXAM AND TREATMENT OF EXISTING WOUNDS. THEN TO CHABUA STOCKADE FOR SAFEKEEPING. |

Perry was taken under heavy guard to the 234th General Hospital. The guards were under orders to shoot to kill should he try to escape. But there was no more flight left in Herman Perry. While evading the MPs he had been shot a total of six times. His accumulated wounds, some of which had not yet healed, and months of jungle living had taken their toll. Adding to his ills, he was now also suffering from dysentery. Still, considering all he'd been through, he was in relatively good condition as Cullum had indicated in his wire to Delhi.

Doctors agreed with Cullum's assessment and Perry was released from the hospital after only a few hours. He was taken to Chabua and confined in an isolation cell surrounded by its own barbed wire. Guards with Tommy guns watched his every move.

During his stay at the Chabua Stockade, Perry spoke with his captors. Some tried to glean information from him about possible accomplices. They were unsuccessful. Most, including Cullum, listened as he told stories of his exploits. He expressed remorse over the shooting of Lt. Cady, but also indicated he would have shot any of his pursuers had the situation presented itself. He seemed accepting of his fate. "If I hang for it, I'll hang like a man."

While on the run, his case had been reviewed and all necessary approvals had been received.

Senior officers ordered details of the execution plans be kept secret, even from the condemned.

They feared that the Jungle King's popularity among his fellow black soldiers might prompt an attempt to free him,

or possibly cause a riot on his behalf.

No attempts were made and no riots occurred.

|

|

|

In the pre-dawn hours of March 15, 1945, Herman Perry was awakened and taken by a convoy of jeeps to Ledo. He was shackled and chained to the floor of one of the jeeps, with 17 MP guards who had orders to summarily execute him should any trouble arise. Major Cullum led Perry to the stockade but chose not to remain for the hanging. He had come to respect his adversary and felt something was not right about this outcome.

About sixty witnesses were present as the Death Warrant was read. Perry's last request was to write a letter to his brother, which he finished with "Don't answer." He was smoking his last cigarette when a guard placed the hood over his head with predictable results. "You trying to burn me to death?" he calmly quipped. He declined the hood but was told it was Army regulations for a condemned man. "Oh well, I don't want to break any rules."

|

The hood went on, followed by a crude hangman's noose, not much more than a slip-knot. There were no experienced executioners in CBI. A ladder propped-up the trap door of the gallows where Perry stood. When the signal was given, the ladder was yanked away.

It took several minutes for the crude noose to have its full effect. MPs waited fifteen minutes just to be sure. A black medic confirmed the sentence had been carried out.

Herman Perry's body was placed in a coffin, taken to the Army cemetery at Margherita and buried behind a hedge, about one hundred yards from all other soldier's graves. A simple white cross marked the otherwise unidentified grave.

Along with his body, the Army also buried his story. There was no official announcement. No story in the Theater newspaper. No official record of the manhunt. If not for Lt. Col. Cullum (promoted one month after the capture) it may have remained that way for good. Years later he would recount his knowledge of the story in a book.

Two days after the execution, Herman Perry's mother would receive a letter from the Army. It indicated only that he had died of "judicial asphyxiation" due to his own misconduct. No details were provided by the Army in the letter. No details would ever be forthcoming from the Army. It would be years before questions about Herman's fate would lead his family to Earl Cullum and the story of the manhunt.

In 1949 the remains of soldiers who died in CBI were repatriated to the U.S. Herman Perry's remains were sent to the post cemetery at Schofield Barracks, Hawaii, where he was buried in an area reserved for soldiers who had been executed by the Army. It would not be until 2007 that his remains were returned to his family. He was cremated and buried near family members in a Washington, D.C. cemetery.

Eventually, a writer researching executions by the Army came across the mention of a murderer put to death by the Army after long evading capture by living with a Burmese tribe. His curiosity would lead him to tell the complete story in a book, the title coming from something Perry said to Cullum on the way to the gallows: "Now, the Hell will start."

CBI MANHUNT

The Story of Pvt. Herman Perry

Compiled from various sources including the book Now The Hell Will Start,

Ex-CBI Roundup magazine, and the Wikipedia and Murderpedia websites.

Copyright © 2014 Carl W. Weidenburner Revised:

Special thanks to Brendan I. Koerner

Learn more about the China-Burma-India Theater at

REMEMBERING THE FORGOTTEN THEATER OF WORLD WAR II

NOW THE HELL WILL START by Brendan I. Koerner AMAZON.COM |

VISITORS