|

|

Walter Orey

Memoir of World War II

In July of 1943, I had been out of high school for a month. Most of my school friends had already turned eighteen years of age and were being called to active military duty. Because I didn't turn eighteen until October, I had a few months to consider my military options.

The Army Air Corps had modified a number of Air Cadet requirements in 1942, that helped me make my decision. The two year college requirement to become an Aviation Cadet was replaced with a qualifying examination. Another modification lowered the age limit from 20 to 18 years. I decided to apply for flight training at the local Army Air Corps Cadet Examining Board located in the Terminal Tower in Cleveland, Ohio.

I passed the qualifying test and the physical examination. I was then instructed to go home and wait for my call to active duty. With all of my friends already in the military, the weeks and months seemed to drag by. I was working as an assistant dispatcher for the Central Greyhound Bus Lines and as I rode the streetcar to work every day, it seemed that I was the only young male not in uniform. On December 23, 1943, I was sworn into the Enlisted Reserve Corps and ordered to report to Keesler Field, Mississippi, in January.

Keesler Field, located on hundreds of acres of white sand next to the Gulf of Mexico, was a beautiful destination for an eighteen year old who had just left a bitterly cold, northern Ohio winter. Basic training for aviation cadet candidates was twelve weeks long in 1944. The climax of our twelve weeks at Keesler Field was the taking of the Aviation Cadet Classification Battery of tests. The memories of those tests are burned into my subconscious, but it would be difficult for me to describe the tests in detail a half century later. However when Pat and I were visiting the Boeing Air Museum in Seattle in 1995, I discovered a book written by Colonel Charles Watry titled Wash Out! The Aviation Cadet Story. The following detailed information about the dreaded Flight Physical Examination and the Classification tests are taken from Colonel Watry's book on pages 49 to 55.

"Developed by psychologists, who were experts in training, the classification battery consisted of three types of tests. The first was a paper and pencil test on a variety of subjects, including general knowledge, graph and chart reading, principles of mechanics, map reading, photograph reading, speed and accuracy of perception, and the ability to understand technical information.The second test was called the psychomotor test which measured motor coordination, steadiness under pressure, finger dexterity, divided attention, and ability to react quickly and accurately to constantly changing stimuli. This test would determine the extent of coordination between eyes and hands and feet.The third part of the test was a private interview with a psychologist. He probed the cadet candidate's personal background, thoughts, preferences and emotional makeup to see what "hang-ups" if any, were apparent.

These three tests, coupled with the most stringent physical examination possible determined whetherthe trainee was to become an Aviation Cadet and if so whether he would have a better chance at success in one or more of the aircrew positions. Of course each of the three tests and physical exam represented a wonderful opportunity to wash out, and this is where the majority of those who washed out in this phase of training did so.

The test scores were expressed in the term "stanine," a contraction of STAndard NINE.This gave the aptitude rating for each man on a scale of one to nine with nine being high and one being low. Navigation training always required a higher "stanine" than bombardier and/or pilot stanines and was pegged at five at the time our class was at Santa Ana. Pilot and bombardier both had a stanine requirement of three. Beginning in December 1943, when quotas for crew training began to be reduced it took a stanine score of seven to enter navigator training and six for pilot. Later scores were increased further.

Prior to the test, we were asked to fill out a form stating our preference for air crew position. Then, handed a special marking pencil, an answer sheet for multiple choice questions, and several booklets, each one covering a different aspect of the test, we went to work. Eight hours later we emerged, exhausted. The next morning it was back again to the paper and pencil testing, which lasted another four hours or so.

No rest for the wicked. In the afternoon, after we had completed our paper and pencil tests, we took the demonic psychomotor tests, which we felt were designed to try to turn us into psychos ourselves. The machines and equipment had been designed by what must have been sadists assigned to the School of Aviation Medicine.The series of diabolical machines had been designed to insure that no one could ever make a perfect score on any of the tests. This was the psychologists' way of differentiating among those being tested to see who was the best of the best.The most vicious of these machines, in most people's opinion, was a thin tapered metal rod which was mounted on a small pedestal about three inches high. The rod was about as long as a pencil. The end of the rod was inserted into a small hole in a vertically mounted metal plate. The test was to see if you could hold the rod in the center of the hole without touching the metal plate. The ringer was that there was a universal joint incorporated in the rod so that there was no hand steady enough to avoid touching the metal plate several times during the time period for the test. Each time the rod touched the metal plate, an electrical connection was made and this turned on a small green light, in a series of green lights, which totaled up the number of your errors. The diabolical thing about the lights was that there were placed slightly above and to the side of the machine, so that you were aware of how many errors you were making as the test progressed. Of course, the longer the test went on, the more frequent were the errors you made.

The next most difficult test for most was another eye-hand coordination test. The machine used was a revolving circular metal plate, much like a phonograph record turntable. Incorporated into the plate was a smaller metal disk about the size of a dime. It was countersunk into the larger plate and its top was flush with the plate. It was placed off center and it revolved also, but in the opposite direction from the larger plate. You were given a wand that was about a foot long with the tip bent 90 degrees down. The idea was to keep the wand in contact with the small disk while both it and the plate rotated. If you could have kept the wand in the exact center of the small disk you would not have scored errors. But this was impossible, and each time the wand slipped off and touched the large plate, an electrical charge counted your error. Errors were scored if you lifted the wand from the small disk as well.

So far the test was not all that difficult. So additional factors were thrown in to test your reaction under stress and to make certain no one could get a perfect score. You were not allowed to see how many errors you made, but you had to count them as you were tested, and then your count was compared to the number the machine recorded. In addition, the instructor circled around you the whole time uttering a continuous patter in a loud stern voice. The patter went like this:"Keep the wand in contact with the small disk. Do not let it touch the large plate. You are being graded! Don't forget to count your mistakes, your count will be compared to the machines. You are being graded! Keep the wand in contact with the disk, each time you lift it or touch the large plate, you have made an error. You are being graded!"

Still another test employed an aircraft control stick and a set of aircraft rudder pedals. Seated in a pilot's position, you faced a series of lights in the form of a "T." There were two parallel sets of lights mounted vertically and two sets of lights mounted horizontally. The machine controlled one of each of the vertical and horizontal sets and you controlled the parallel sets with the stick and rudder petals. There were about 10 or 12 lights in each set. Your light in each of the sets was yellow and two lights remained on all the time, dependingon the position of the controls. The machine's lights were all extinguished. Suddenly the machine's green lights, one in each set, would come on. You were to match the position of your two lights with the two lights the machine activated, using the controls. When you matched your lights with those of the machines, its lights would extinguishto come on again in different positions. The speed with which you matched the machine was the basis of the test. This test was not too difficult for those of us with flight training, but then, we never knew what the speed criterion was either.

Another test involved seeing how fast you could turn pegs in a board around 180 degrees, which probably measured finger dexterity for actions like operating cockpit switches or bombsight controls.Each test was given in a separate room, and we were alone with just the instructor. The walls, ceilings, and floors of the rooms were painted black and there were no windows. The only illumination in the rooms was a single spotlight on the machine. We never saw the instructor; he constantly moved about in the shadows of the room telling us what to do, and, in at least one case, berating us. We were not told our stanine scores on the psychomotor tests.

The third and final examination in the classification battery followed a day or so after the psychomotor tests. Psychologists interviewed each cadet individually, asking a variety of questions, including, "Do you like girls?" and "Do you have a girlfriend?" and "How long has it been since you wet the bed?" Then, as now, the Air Force did not tolerate bed-wetters.

The eye tests are the most feared parts of the exam by most pilots, and naturally, the results are important to the outcome of the exam. There were no less than 12 eye tests given to us that day, including color, distant vision, near vision, accommodation and several others. The most feared of the eye tests, and the one that trapped and sank the majority of cadets in our group who failed the physical for eyes, was the depth perception test.

Part of the problem was the seemingly archaic machine that was used. It consisted of a box with a rectangular hole in one side. Inside the box, and viewed through the rectangular hole were two vertical white sticks mounted so as to slide toward and away from the person being tested. Attached to each stick was a long string by which the position of the sticks could be manipulated. The box was lighted on the inside. When it was your turn to be tested, you were seated on a chair at the end of the strings, about 20 feet from the box and facing the rectangular hole. The corpsman administering the test, using the strings, placed the two sticks in alignment, so that both were exactly the same distance from you; then he showed you how to move them back and forth to get them aligned. Then placing them off alignment, he laid the strings stretched out in front of you. You then picked up the strings and tried it yourself. If you didn't align them within limits the first time, you were allowed another try.

The test was made difficult because of the restrictions inherent in the test which limited one's ability to judge the relative position on the two sticks. First off, the size of the rectangular hole eliminated the opportunity to move one's head to the side to get a quartering view of the two sticks. You had to face them head on. Then the inside of the box was arranged so that there were no shadows to help you gauge the movement of the sticks. The sole way to judge their relationship was by the relative width of the sticks. And doing this for two half-inch-wide sticks at distance of 20 feet was no mean feat. Most of us used the techniques of moving the sticks to the limit of their travel in both directions to get a perspective at the extremities and then fine tune their positions somewhere in between.

The flight physical took its toll of our friends. At the time we estimated that about 20 percent of those who had survived the enlisting physicals were washed out by the rigorous flight physical. They left for a base at Fresno, California the same day where they would be processed for reassignment to other training."(Col. Charles A. Watry)

In the spring of 1944 the stanine scores were raised again washing out about 70% of the Aviation Cadet candidates in our squadron including me. All of the washed out cadets were given a fourteen-day furlough with orders to report to Hammer Field, located near Fresno, California. Most of the washed out cadets believed the "stanines" were raised in response to a sharp reduction of requests from overseas combat commands for replacement air crews.

Only recently did I discover a book that provided another explanation for the cutback of the aviation cadet program. The book's title is Scholars In Foxholes! The Story of the Army Specialized Training Program in World War II by Lewis Keefer.

Lewis Keefer stated there was enormous political pressure to sharply cut back the Army Specialized Training Program, as well as the Army Air Cadet Program early in 1944 to save more than 200,000 pre-war fathers from the draft. The Army decided to curtail both its ASTP and the Air Cadet Program. The War Department announced in January, 1944, that 70 colleges would lose all their Air Cadets. The fate of many air cadets paralleled that of the ASTP students. They were selected for a special program, filled with great expectations, then with little warning transferred to the Army Ground Forces. The washed-out cadets and the ASTP students were spread widely among receiving units to fill personnel shortages.

In the spring of 1944, my elimination from the cadet program was devastating to me. I continued to correspond with two of my fellow Keesler Field Cadets who survived the raised "stanines." Both of them were assigned to a pool of qualified candidates for the Army Air Corps Cadet Program. The pool was created by a reduction in flying training programs in response to the success of the air war in Europe.The new plan was called "on the line training" and provided on-the-job instruction in air craft maintenance to those who were waiting for training assignments. On-the-line training began in February of 1944, and by July was the major holding device or those awaiting flight training. By the end of 1944, most pre-flight Air Cadets had been on-the-line training status for nearly a year.

"The official explanation, that the cutbacks in the flying training program were because of unexpected combat successes, was hardly a consolation to many disappointed and bitter young men." (WASH OUT!, page 42)

When I reported to Hammer Field, California, in April of 1944, I discovered many of my Keesler Field friends had also been ordered to report to Hammer Field, California. Most of us were assigned to the 1891st Aviation Engineer Battalion, then training at Geiger Field, Washington, for an overseas assignment. Within three months the 1891st Aviation Engineer Battalion was aboard a troop ship, on its way to the China-Burma-India Theater of War.

After the war was over, I realized how fortunate I was to have had the opportunity to help build airfields in Burma and China during the war rather than spend that time as an on-the-line pre-flight Air Cadet.

|

to Assam, India

A significant number of ex-cadets from Keesler Field, were assigned to the 1891st Engineer Aviation Battalion, stationed at Geiger Field, Washington, in April 1944. The mission of our newly assigned unit was to complete its advanced airfield construction training, preparatory to an overseas assignment.Although I still felt badly because of my elimination from the Air Cadet program, I began to adjust. Spokane, Washington was an attractive city, and the girls we met at the U.S.O. were friendly. Army food, served family style in small company mess halls, was far superior to the cafeteria style, consolidated mess halls at Keesler Field. The 1891st began to train its influx of newly assigned 18-year-olds as earthmoving equipment operators and drivers.It seemed to me that all the enlisted men were either privates or senior sergeants. The Battalion was burdened with a major surplus of N.C.O.'s (Non-Commissioned Officers) in the first four grades. Due to the fact that the policy was not to reduce those men to a rank equal to their T/O positions and/or assignments; the promotion of other qualified men was frozen. Very few of the ex-cadets were ever promoted beyond the rank of corporal.Our four-week bivouac in the national forests of Idaho, helped prepare us for our future living conditions overseas. In mid-August, the Battalion received its orders to report to Camp Anza, California (Los Angeles Port of Embarkation). In May, I had been assigned to the Headquarters and Service Company. They were the last company to board the troop train leaving Geiger Field. The base band played "Auld Lang Syne as the men of the 1891st waved to those outside the train. Soon Geiger Field was but a memory.

An N.C.O. was in charge of each car in the troop train to make sure that the car was kept clean and orderly. Guards were posted at both doors so that no one left the car at stops along the way. Food was carried from the mess car and distributed to the men in their own cars. After three days of traveling, the train pulled into Arlington, California on August 16th, 1944.To me, Camp Anza seemed to be nothing but thousands of tents located in a desert. There were countless "standby formations and "clothing inspections." Passes were issued to visit nearby towns and cities. I went into Los Angeles to visit my aunt, Sister Bernardine. I was the guest of honor at her convent that day. Everyone seemed happy to leave Camp Anza as we boarded the train that would take us to the L.A. Port of Embarkation located in Wilmington, California.In Wilmington we boarded the troop ship, the General Randall. The General George M. Randall was the biggest ship most of us had ever seen. It cast a huge shadow on the dock as we ascended its gangplank. The General Randall could carry thousands of troops. The decks below the main deck were packed with bunks suspended by steel frames and chains. The canvas bunks were stacked five high with about 18 inches of space between bunks.Conditions on the ship were less than pleasurable. The soldiers were only served two meals a day. The showers were saltwater showers which meant that you felt sticky most of the time. None of the enlisted men were allowed on deck after the sun went down. We also had some rough weather. We could hear the churning of the ship's propellers as they left the water between the huge swells and waves. Many of the soldiers were seasick and they carried their steel helmets everywhere, to catch their vomit. Fortunately there were a lot more smooth sailing days than rough weather days.

In early September the ship crossed the equator. The sailor shell-backs (those who had already crossed the equator) sadistically enjoyed initiating the polliwogs (those troops aboard ship who had not crossed the equator). A few days after crossing the International Date Line, the ship docked at the Port of Suva in the Fiji Islands. There was no shore leave for the troops, but we did participate in a foot march through the town.By now there were rumors that the ship would stop in Australia. A few days later the ship did dock in Melbourne, but we were told that Australia was not our final destination. Only controlled marches were allowed in Melbourne. Even the controlled marches were canceled after the first day when some men broke ranks to explore the side streets of Melbourne on their own.When we left Australia we became part of a convoy protected by a British cruiser and two Dutch destroyers. Up to this point there was considerable speculation, among the men, as to our final destination. As the ships traveled west for more than 1000 miles, and then headed into the Indian Ocean, it became obvious that we were headed for India. After many days of terrific heat, our ship docked in the Port of Bombay. We had been on the General Randall for 38 days.

The train ride from Bombay to Dibrugarh took nine days. Living conditions on the train made our sea voyage seem less harsh. We ate K-rations; a K-ration was a packaged meal for one man, meant to be eaten cold. We supplemented our K-rations with fresh fruit that we purchased from the Indians. We were warned to eat only citrus fruits and bananas with unbroken skins. In addition to fruit vendors, our railcars would be surrounded by children begging and shouting "Bahksheesh!" Bahksheesh meant free handouts, especially food.The train was on a wide gauge track and the cars were wider than trains in the United States. The seats on each side of the coach accommodated the 8 soldiers assigned to each compartment. Four additional bunks were folded up above the two bunks used for seating. Two of the eight men assigned to each compartment took turns sleeping on the floor of the train. When the train stopped, and it did often, we secured boiling water from the locomotive to make tea.Malaria was a common and serious disease in India. For malaria control we were ordered to (1) take Atabrine tabletson a daily basis, (2) apply insect repellent to our exposed skin and (3) spray our compartment with an "aerosol bomb" containing DDT. After each spraying, hundreds of insects would exit the straw filled mats covering the seats and bunks. We would then step on them as they scurried across the floor of the compartment. We were also warned not to go barefoot because of hookworm disease.

A rather interesting sidelight was the toilet facility in each compartment. The toilet was a hole in the floor with an upright pole to grip as the train rolled from side to side. How ironic I thought, as I relieved myself over a hole in the floor in front of seven other men, that in high school I was reluctant to use the stalls in the boys restrooms because they lacked doors that could be closed for privacy.After a week on the wide gauge train, we transferred to a narrow gauge train. When we reached the Bramaputra River it was necessary to leave the train so we can be ferried across the river by boat where we boarded another narrow gauge train. We arrived at Camp Galahad in mid-October.Camp Galahad had recently been evacuated by Merrill's Marauders, the well-known American combat task force. Camp Galahad was in a deplorable state. Tents were hanging partly on the ground, beer bottles and discarded personal equipment were everywhere. With the concentrated efforts of each company the area was looking fine within a few days. Camp Galahad was near Dibrugarh in Assam Province. It would be our home base until we were flown into Burma.

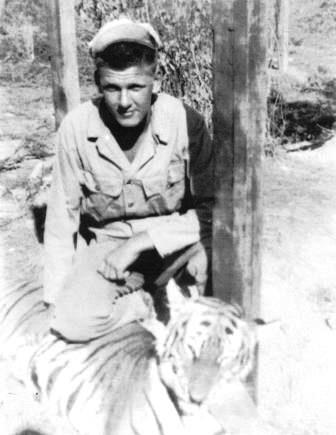

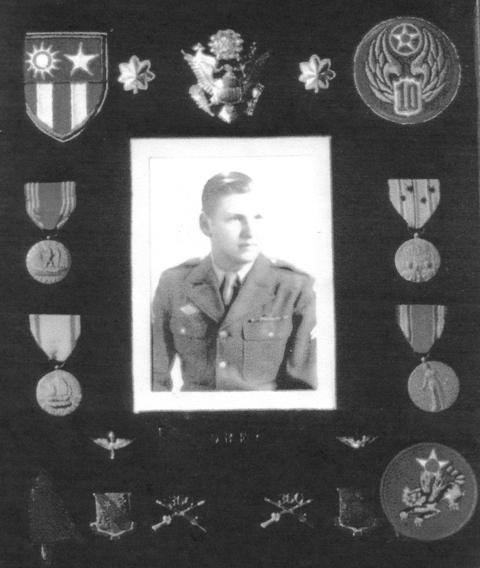

Merrill s Marauders On October 21st, 1944, the battalion's heavy equipment began to arrive from Calcutta. Because we were going to be flown into Burma by C-47 aircraft, much of our equipment had to be dismantled to fit the aircraft.The first plane left Dinjan on 27 October for our mission which was the construction of Myitkyina Airfield, East.The airfield was to be 5000 feet long by 150 feet wide with 19,000 feet of taxiway. A fighter dispersal area for 52 planes was to be constructed in conjunction with the airstrip. Myitkyina (generally pronounced (mitch-in-ah) had only recently been taken from the Japanese by American trained Chinese infantry and what was left of Merrill's Marauders. The place was a mess with battle-damaged equipment and buildings all over the place. Many unburied Japanese were still to be found in the jungle around Myitkyina.Because the 1891st Engineer Battalion was the first unit to occupy the former camp of Merrill's Marauders in Dibrugarh, and it was now our mission to construct an air field where the Marauders fought their last and most ferocious battle. I think it appropriate to include some information about Merrill s Marauders.The origin of the unit began in August 1943 when the War Department decided to organize three independent infantry battalions to be used for long-range behind the lines penetration missions in Burma. To secure these volunteers, a directive from Washington was read aloud at formations in the South Pacific and the Caribbean Defense Command including the specific statement that what the volunteers were wanted for "was a dangerous and hazardous mission." They were to be battle tested or jungle trained volunteers. Three thousand men were selected from the volunteers already in the South Pacific, or from jungle-trained units stationed in Central America in the Caribbean Defense Command. This American infantry regiment, of three battalions, was given the name "Galahad" by the War Department. In December of 1943, Galahad went through several reorganizations in India. It was given the official name of the 5307th Composite Regiment. In January, Brigadier General Frank Merrill was given command of the 5307th.A few days later, the 5307th was changed from a Composite Regiment to a Composite Unit since it would not be fitting for a regiment to have a general officer commanding it. Shortly after that, the unit was usually referred to as Merrill's Marauders. Prior to entering Burma the 5307th received 700 pack animals to carry their supplies ontheir assigned long-range penetration of Burma, then under total Japanese military control.Thus began what they were told would be a three-month penetration of Japanese held northern Burma. American and Japanese troops were always running into each other. There was no front to speak of in the kind of fighting that developed. Marauders killed by the Japanese, were buried in the jungle. When possible, the wounded would be flown out in Piper Cubs. The 5307th was supplied by the Combat Cargo Groups of the 10th Air Force. The 5307th was responsible for creating tiny air strips where Piper Cubs could land and also to cut trees to create drop zones for their aerial re-supply. The appearance of the supply planes often meant that the Japanese would know where the Marauders were.It is impossible to describe in detail the hundreds of combat contacts the Marauders had with the Japanese. The following paragraph might be a typical description of their uncounted firefights. This description was taken from page 213 of Merrill s Marauders by Charlton Ogburn. "We have about 100 wounded, 17 dead, and 4 missing to date in Nhpum Ga. The stink of the dead horses and men grows worse. Water was dropped again today. The planes seem to draw unusually heavy ground fire. Four of the 18 aid men in the battalion have been wounded. Three men that were wounded and were sent back to the perimeter, after having their wounds dressed here, have been killed. Many of the wounded refuse to stay in the aid station and they insist on returning to the perimeter where they know they are sorely needed." In April, the Marauders were waiting to be relieved by a regiment of the Chinese 38th division. Then a grotesque rumor began to be passed along, pretty much as a joke. The substance of the rumor was the possibility of the 5307th being sent against the Japanese in Myitkyina. What the 5307th felt was that while Myitkyina was important, so was Shanghai, there was about as much chance of its being able to take one as the other.There was one compensation. The Marauders probably could not reach Myitkyina, but if they did, they would wind up with glory and honor and a fling that could make history. This was positively to be the last effort asked of them.They had it from General Merrill that when they had gained their objective they would be returned to India, given a big party, installed at a well appointed rest camp, and given furloughs. It was this prospect that gave the 5307th the resolve to surmount the obstacles that lay before it on the trail to Myitkyina.In May, General Merrill informed his three battalions that their new objective would be the airstrip in Myitkyina. The men were scarcely ever dry on their jungle march to Myitkyina. When it was not raining, the jungle steamed. For the first-time soldiers of the 5307th began to pass men fallen out beside the trail. Men who were not just complying with the demands of dysentery, but were sitting bent over their weapons, waiting for enough strength to return, to take them another mile. When the Marauders and the Chinese infantry reached the Myitkyina airstrip they discovered that the Japanese had pulled back from the airstrip, into the jungle, when the American bombers came over. The 5307th and the Chinese captured the airstrip with minimal losses only to discover that a strong force of Japanese still occupied the town of Myitkyina. Back at his headquarters, Stilwell was exultant. Again and again he had been told that Myitkyina could not be taken. Now his transports were landing on the Myitkyina airstrip, flying in more American-trained Chinese infantry.In six months his forces had driven 500 miles into Burma and won engagements against seven Japanese regiments, among them, the victors of Singapore. The brilliant seizure of the Myitkyina airstrip was the height of Stilwell'scareer and the grand climax of North Burma campaign.Stilwell was not given long to enjoy his triumph. There were ominous developments almost from the start. The plans Merrill had made for supplies and reinforcements were not carried out.The Chinese and American forces had been thrown off balance by the ease with which the airstrip had been taken and had no strategy with which to follow up their initial success. When the Japanese, in May, began to take the initiative, the Marauders took the first blows. Galahad was now practically unfit for combat. They had been promised that with the capture of the airfield its personnel would be flown out for rest and reorganization, neither of which had been carried out. A few days later the commanding officer for the 5307th declared it unfit for further combat and requested its relief. Only 200 of the 3,000 men with which the 5307th had started were considered fit to remain at Myitkyina. Through the wards and convalescent camp at Margherita raced a piece of stunning news. Orders had been issued that any of those in the 5307th who were able to walk were to be rushed to Myitkyina. Stilwell's headquarters were placing extremely heavy pressure, just short of outright orders, on medical officers to return to duty or keep in line every American who could pull a trigger. The medical officers were loath to certify as fit, combat men who were broken physically, but they were still used to capture Myitkyina. In mid-August the Chinese and the 5307th finally overcame the resistance of the Japanese.When the 5307th came to its end, there was not even a final formation. The outfit had simply trickled away. The day after the battle of Myitkyina was concluded, the War Department bestowed upon the 5307th the DistinguishedUnit Citation.Much of the information in this chapter was common knowledge among the men who followed the Marauders into Burma. The more detailed information such as dates, unit designations, higher headquarters information, etc. I found in the book titled by Carlton Ogburn.When writing this chapter about Merrill's Marauders in June 1999, I checked the Internet to see what information may have been available. I discovered a good first person account of the Marauders by Capt. Fred Lyons (as Told to Paul Wilder in 1945). Myitkyina and Bhamo An advance party from the S-3 Section of Headquarters Co. was flown into Myitkyina in October 1944. Their mission was to prepare a site for the Myitkyina East airfield. Within a couple of weeks, A, B, and C Companies were flown into the Myitkyina area. The area was exceedingly difficult to clear because it was pitted with Japanese, Chinese, and American earthen fortifications, fox holes, and all the imaginable gear of battle. Twelve-hour work shifts were established and soon the construction of East Myitkyina airstrip began to take shape.We usually carried our assigned weapons with us when working on the airfield because of Japanese snipers. Many Japanese soldiers fled into the jungle after the battle of Myitkyina and they were a problem for several months. Some nights Japanese bombers would circle over Myitkyina to harass us. The sky would then light up with anti-aircraft fire. With few exceptions, the most damage caused by the bombers was the deprivation of sleep and rest. We were free to explore and/or to hunt in the jungle surrounding Myitkyina when we were not working. I hunted with my Garand M-1 semi-automatic rifle. I also carried a Colt .45 caliber pistol that my father had sent me when I was overseas. Several men in the battalion bagged tigers. On our early jungle explorations, we would sometimes stumble across unburied Japanese soldiers. The things I most remember about those dead soldiers were their canvas and rubber boots. The toe portion was different from any shoe or boot that I had ever seen. It had two sections, a small section for the big toe and a larger section for the other four toes. I guess they were made to accommodate the feet of men who had grown up wearing sandals with a strap between their large toe and their remaining toes. The Burma Road By 1937 Japan had occupied most of China's major cities until China was effectively cutoff from the rest of the world. To maintain imports of strategic goods and relief supplies, China had built a 600-mile road to Burma in 1937. Virtually all supplies to China had to make their way by ship to the Burmese port of Rangoon, and then by rail to Mandalay, and into the mountains to the railhead at Lashio, where the Burma Road began its hairpin course through high passes to Kunming, China.In 1941 the Japanese armies thrust into British Burma and successfully destroyed the British defenders in 75 days. The loss of Burma effectively closed the Burma Road and cut off China from the outside world. In 1942 the U.S. Army engineers began the Ledo-Burma Road project. A new 500-mile road would have to be carved out of the jungle from Ledo in Assam, India to Mong Yu in northern Burma. If the two roads could be joined they would provide an overland supply route from India to China. All told, 28,000 engineering troops and 35,000 native workers labored for more than two years to complete the Ledo-Burma Road. The road's construction, along the edges of 8,500-ft. defiles, down steep gorges, and across raging rapids in some of the world's most impenetrable jungle stands as one of the great engineering feats of World War II.The long and arduous struggle that had been going on since the Japanese invaded Burma in early 1942 was now entering its final phase. In the middle of October 1944 the Chinese, British, and American forces had taken the offensive in a drive to wrench the Burma Road from Japanese control. Chinese forces, spearheaded by the U.S. Mars Force, pressed rapidly across northern Burma toward the Chinese frontier. In late January 1944 they finally reopened the overland route to China. In January of 1945 the first official convoy pulled out of Ledo for Kunming over the newly finished Ledo Road. Steep road grades frequently slowed the convoy to a crawl. When the convoy reached the Burma Road, it was held up while Chinese soldiers cleared the area of lingering Japanese troops. Finally after almost a month of hard travel, over the 1,726 mile route, the first convoy rolled into Kunming. Our journey from Bhamo, Burma to Kunming, China would be a little over 1,100 miles. That distance would be driven in a day or two on modern paved roads, but it took us more than two weeks to reach Kunming. It should be clarified that the Burma Road was a "One Way Road." No vehicles were ever driven out of China. In fact the only vehicles on the Burma Road belonged to the U.S. Army and they were all going into China. Our convoy was totally self-contained. We carried all of the food, gasoline, and other supplies that we would need for the next half-month. The drive was rather lonely. We never saw the convoy ahead of us or the convoys that had to be behind us. Most of our vehicles had only one person in them, the driver. The convoy would begin rolling at 0600 each day,and except for short breaks we would drive until the sun went down. Breakfast and our noon meal were K-rations. Our evening meals were C-rations, usually warmed in water heated in our helmet. C-Ration for one man consisted of two small cans. One can held about eight ounces of stew or pork or another food that could be heated in hot water.The second can held crackers or biscuits and powdered coffee or chocolate. Every night we would refill our fifty-gallon gas tank with fuel from our unit's gasoline tank-trucks using each truck's five-gallon gas can. After repairing flat tires, and checking our engines, we were free to bed down. Each soldier had been issued two blankets, (sleeping bags did not seem to have been issued in the CBI Theater of War) and most soldiers slept beneath or next to their truck. The steepness of the grades and the thousands of hairpin curves were the causes of the convoy moving so slowly. We averaged less than 90 miles a day. Now and then we would see Chinese soldiers who had been trained in India, fought in Burma, and were now returning to China on foot. Sometimes a bridge would be out, or perhaps damaged, and then our vehicles would have to be ferried across rivers.One special memory of our journey over the Burma Road was receiving news that President Roosevelt had died. Hearing the radioed reports of the president's death, in the dark, on a road somewhere between Burma and China made us very aware of how far away from home we were. China - April 1945 to August 1945 The Burma Road wasn't much more than a refinement of the ancient Marco Polo Trail. The blood and sweat of the Chinese laborers who lived along the road accomplished the improvements and maintenance of the road. Occasionally we passed such a community, the Chinese, especially the children, would rush out and shout "Ding Hao"(very good) and display an upraised thumb.We became quite excited as we anticipated our arrival in Kunming. We had heard that Kunming was one of the largest cities in free China, and we expected that it would be quite a contrast to the small jungle villages in Burma. To me, an unforgettable sight was the massive stone arches that framed the main entrance to Kunming. The arches had impressive tiled roofs and glittering letters of painted gold.I quickly discovered that nothing in my 19 years of living resembled the sights, sounds and smells of Kunming. Practically all of the civilians wore blue cotton jackets and trousers. Beggars with misshapen bodies were a common sight along the narrow alleys. Water buffaloes pulling heavy loads crowded the roads in town. Wagons, drawn by ponies that carried up to a half-dozen Chinese were all over the city. They served as the public transportation system supplemented with hundreds of rickshaws. There were no civilian cars to be seen in Kunming. I did see a number of dilapidated coke-burning trucks on the streets. Most of them were overloaded with a dozen or so passengers sitting on top out whatever the truck was carrying. There was no way to describe the sense-deadening odors that assaulted our sense of smell as we entered Kunming. It was not until three months later when I returned to Kunming from Mengtze that I discovered that Kunming did not have a sewage system. The battalion only stayed in Kunming long enough to deliver the several hundred extra vehicles that we had driven, from Burma to China, to the United States Army Quartermaster Corps. The 1891st Engineer Aviation Battalion had orders to report to the town of Mengtze, about two hundred kilometers south of Kunming. Mengtze was located just north of the border of what was then was called French Indo-China, but today is Vietnam. The battalion's mission was to construct an airfield for General Chennault's expanding 14th Air Force.When we arrived at Mengtze most of us were surprised to see thousands of Chinese laborers building an airstrip by hand. Instead of large rock crushing machines, the Chinese were using hammers to reduce large rocks to smaller rocks. In place of bulldozers, they were using water buffalo to haul large bamboo baskets of rock. Instead of trucks, Chinese men and women carried baskets of stones on shoulder yokes. These smaller stones were chipped to proper size and then were laid by hand by adults and children. The hand-laid stones were then compacted by a multi-ton, solid rock, roller pulled by a hundred or more men. Some person of importance or influence made the decision that these thousands of Chinese laborers would continue to work on hand construction of a portion of the air field at Mengtze while the 1891st Battalion would use its modern equipment to complete the rest of the air field.My personal contribution to the construction of the two airfields built in Burma and the airfield under construction in Mengtze was of a very modest significance. In Burma I was assigned to the Headquarters Company motor pool. That meant that my primary assignment was driving a variety of wheeled vehicles. Most days or nights I hauled gravel from the nearest riverbed to a taxi or runway site in a two and one-half ton, 6 by 6 (6 wheels/6 driving wheels), GMC, dump truck. And other times I drove a three-quarter ton, 4 by 4, Dodge, weapons carrier, taking supplies to A, B, and C Companies. Later in China I got a chance to work with some tracked earth-moving machines. On the job training made me proficient enough to operate small bulldozers. While at Mengtze I was surprised to discover the French had built a narrow gauge railroad between Haiphong in French Indochina and Kunming, China. In the late 1930s the United States and Britain shipped supplies and munitions to China over this railway because the Japanese controlled all of China's seaports. When France was overrun by the German army in 1940, the Japanese occupied the French colony of Indochina and cut the railroad route into China. China then became totally dependent on the Burma Road for military supplies from the free world. In July three men were selected the from Headquarters Company to maintain the asphalt surface of the airfield in Kunming. I was one of the three men selected for the maintenance team. It turned out to be a great assignment. Our home was a small wooden shack adjacent to the Kunming air field. We ate in a nearby 14th Air Force mess hall. We had a job, we did it, and no one of higher rank ever bothered us. It also gave us the opportunity to see more of Kunming. There was a beautiful lake outside of Kunming. A picturesque canal connected Kunming Lake and the city itself. The lake and the canal contained thousands of houseboats and sampans. The boats were great importanceto the transportation system in Kunming. In addition to their importance as a means of transportation, the numerous little boats helped relieve the acute housing problem in Kunming. The tiny bamboo covered cabins, open at one end, served as the kitchen, and dining room, and bedroom for the entire family. We were told that when the father dies, the oldest son inherited the ownership of the little boat and he assumed the responsibility for taking care of his mother.The Kunming Canal served many other purposes in addition to transportation and housing. Mothers washed the family's clothes in it, and children filled buckets for cooking water. Pigs, water buffaloes, and horses drank from it. The canal also served as the irrigation source for the rice paddies on either side of the canal.I was somewhat fascinated by an ingenious design of clothing for smaller children. Most small children in China wore trousers that were slit to the waist front and back. When a child squatted to relieve him/herself the pants opened up allowing their waste to drop to the ground without soiling the child's clothing. No diapers, no mess; except for the mess that you had to avoid stepping on. Things were not going well for the Allies in China in 1944 and 1945. The Japanese, whose army controlled most of eastern China for a decade understood that it was only a matter of time before American B-29s would be using bases in China for raids against Japan. In 1944, Japanese forces in China were ordered to capture and destroy the 14th Air Force bases in western and southern China. The Chinese armies were unable to stop the Japanese who overran seven Chinese-American air bases. The Japanese offensive in China was the most serious offensive Japan managed to launch during the final two years of the war. Japanese ground forces never seriously threatened the air strip under construction at Mengtze but we were subjected to bombings at night.Although it was true that the 14th Air Force pretty much controlled the skies of western and southern China, the Japanese army was still the dominant ground force in China. The Chinese armies could not stop the Japanese from going wherever they wanted to go.For the reader to better understand what was going on in other parts of the Asiatic-Pacific Theater of War, I would like to share the following information. In June of 1944, Admiral Nimitz's forces in the Pacific consisting of more than 500 ships and 130,000 Marines and soldiers attacked the island of Saipan. Nearly half of the American troops that went ashore at Saipan were killed or wounded. A year later the Marines landed on Iwo Jimafor what their commanders thought would be a brief, but bloody battle that would last three or four days. Instead, five weeks of bitter fighting were required to take the eight mile square island. All but 212 of the 21,000 of Iwo Jima's defenders fought to the death, while 26,000 Americans were killed or wounded. The eleven week Okinawa campaign that began on April 1 of 1945 had been one of the fiercest of the war, killing more than 7,000 Americans and wounding more than 31,000 G.I.s and Marines. I mention these battle statistics to assist readers who were not in World War II to better understand of the thinking of the typical G.I., Marine, or sailor when they heard about atomic bombs falling on Japan. In August of 1945 when we heard that the 20th Air Force had dropped something called an atomic bomb on Hiroshima totally destroying the city, most soldiers that I knew, wanted to know when the next atomic bomb would be dropped. Three days later, a second atomic bomb was detonated over Nagasaki. Again the effects were awesome. The Japanese Supreme War Council gave in to the inevitable and on August 14, 1945 decided to capitulate. On August 15, in a taped radio message, Emperor Hirohito informed his people that the years of fighting were over. Going Home - August 1945 to March 1946 On August 26, Lord Mountbatten accepted the Japanese surrender of South East Asia in Rangoon, Burma. Two days later, August 28, American troops began a mass and unopposed landing on Japan's home islands. There were several, separate, Japanese capitulations on widely separated fronts, including a Japanese Army delegation flown into Kunming in planes with green crosses painted over their regular "Red Rising Sun" The historical act confirming Japan's defeat took place aboard the battleship U.S.S. Missouri on September 12th 1945, in Tokyo Bay.Now that the war was over, plans had to be developed to return the millions of soldiers, sailors and Marines overseas, to the United States. Many questions had to be considered. Who would serve in the army of occupation? In what order would the troops overseas board the troopships for home? In what order would those in the armed forces be discharged?A plan to return the troops overseas to the United States and to discharge military personnel in the United Stateswas based on a point system. Each month of active duty would be worth "X" number of points. Months served overseaswould be worth a greater number of points than months served stateside. Military decorations would count as discharge points. Bronze battles stars issued for serving in campaigns would be worth points. I had only been on active duty for 21 months when Japan surrendered, but I had been overseas for a year. The 1891st Engineer Aviation Battalion had participated in four campaigns, India-Burma, Central Burma, China Defensive,and China Offensive. Collectively my 12 months of overseas duty plus my four bronze battle stars helped me considerably but it would still be close to six months before I would be on a ship headed for home.With the accelerated evacuation of United States Forces in southwest China, new construction work ceased and our post war mission was the maintenance and repair of the Air Transport Command air fields at Kunming, Chungking, Luiang, and Chanyi, all in Yunnan province. Each of the four companies in the battalion was assigned to one air base. The Headquarters and Service Company was sent to Kunming. Headquarters and Service Company personnel were occupied with maintaining the Kunming Air Base and with getting our equipment in shape. By mid-October many of the Army Air Corps units had left for the port of Calcutta in India, allowing the enlisted men in the battalion to move into their former barracks. This was the first time since arriving overseas that we lived in real buildings. The ex-cadets assigned to the 1891st Battalion in May of 1944 were the short-timers in our outfit compared to most of the men in the battalion. I had just had my 20th birthday in October 1945 and I began to wonder when it would be my turn to return to the United States. The Army was offering to fly soldiers home for Christmas if they would reenlist for the Army of Occupation.November was spent "closing down" many of our activities and was highlighted by the departure of our senior officers and noncommissioned officers. It became difficult to keep up with all of the personnel changes as a more and more men were flown from Kunming to Calcutta.Later in the month all United States military personnel were confined to the air base for several days when sporadic fighting broke out among the Chinese forces in Yunnan Province. We did not know it at the time, but it was the beginning of the civil war between Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalist Armies and the Chinese Communist Army under Mao Tse-tung. This struggle for control of China continued until 1949 when the Communists won control of the entire Chinese mainland, and Chiang Kai-shek and most of his army fled to Taiwan. In early December we received orders to fly to a staging area near Calcutta, India. When we reported to the Kunming Air Base tarmac we discovered that our plane was going to be a C-46 Commando. The C-46 was the largest heaviest twin-engine transport used by the Army Air Forces in the war. The C-46 had twice the tonnage capacity of its predecessor, the C-47. We had talked to air crews in the mess halls in Kunming and they often complained about some of the problems that their C-46's had experienced flying over the "Hump." In heavy rains, the fuselage leaked from poor joint seals. At high altitudes faulty defrosters caused the air intakes to clog with ice. Even more hazardous were fuel line breaks that spewed gasoline on hot engines. After the war I read that scores of C-46'shad crashed in the rugged country between India and China, because of these defects. We boarded our C-46 with some apprehension. The good news was that the fuel lines did not spew gasoline on the hot engines on our flight from Kunming. In addition, the planes now flew a lower, less hazardous, route to India because there were no Japanese fighters attempting to shoot them down after August 1945.Our plane landed at Dum Dum airport and we were trucked to a huge staging area covered with hundreds of white British army tents. This area would be our home until it was our turn to board a ship in the Bay of Bengal, about 60 miles south of Calcutta. We did have several opportunities to visit Calcutta. Calcutta was then India's largestand most populous city.I had seen some severe poverty when we landed in Bombay, and when we crossed India by train, but the poverty witnessed in Calcutta was overwhelming. Slums seemed to be everywhere. The houses we saw, as we walked the streets, were very small and were built of flimsy materials. The slum areas lacked underground sewage systems. Some public latrines seemed to be simply large holes in the ground where people relieved themselves. Public water pumps were often crowded with men and women and children as they attempted to wash and bathe themselves. Most people also secured their drinking water from the same public water pumps. The Hooghly River ran through Calcutta and people bathed in the river and also secured their drinking water from the same river. In the evenings, hundreds of residents, called "pavement dwellers," could be seeing lying on the sidewalks and other paved areas that were covered by a roof or an overhang that would protect them in case the rain. The temperatures in December and January, when we were there, were so mild that the "pavement dwellers" did not need blankets to keep warm as they slept in public places. Most of the streets were congested with people, cows, slow moving buses, and hand pulled carts.We were told that Calcutta had been founded by an English trader, 250 years ago. According to British soldiers, the city became famous in 1756 when a Bengal ruler captured the English Fort William and crammed 43 British residents in a small guardroom, suffocating them. The guardroom has been called The Black Hole of Calcutta ever since. My second Christmas overseas was celebrated in our camp near Calcutta. I attended Midnight Mass on Christmas Eve. Christmas was a very warm day. We enjoyed a better than average dinner in our mess hall on Christmas day. There were no Christmas trees. No presents were exchanged. We all dreamed about being home for Christmas. In some ways, we were all forced to think about the real meaning of Christmas, without the distractions that cloud the celebration of Christmas in our modern, materialistic society. All the men being processed at Fort Lewis were issued the medals and decorations they were authorized to wear. I received the Asiatic-Pacific Theater War Medal, with four bronze stars, the Good Conduct Medal, the China Service medal, and the Victory medal. We were then put on troop trains going to regional Army Separation Centers. Camp Atterbury, Indiana was my destination. Final pay disbursements were made at Camp Atterbury and Honorable Discharges were issued. Fifteen dollars and eighty-five cents was given to me for travel from Camp Atterbury to Cleveland Ohio. I used the $15.85 to purchase a Greyhound bus ticket to Cleveland. I wanted to surprise my family and I did. When I walked into my home unannounced on March 7, 1946 there was a whole a lot of hugging, and happy tears flowed freely.

As the American-trained Chinese infantry liberated more of northern Burma, the need for an airfield at Bhamo became apparent. A higher headquarters decision was made that an airfield at Bhamo would be constructed by A and C Companies of the battalion. Headquarters and B Companies would remain at Myitkyina to complete the airfield there.The area around Myitkyina was changing quickly. Gone was the dense jungle that covered the centerline of the runway. The trees surrounding the air strip site had been penetrated with taxi-ways and hardstands. Tents were beginning to pop-up around the airstrip to house the men from B Company and Headquarters Company.No country of its size had a greater variety of tribal and racial groups than Burma. More than a hundred languagesand dialects were spoken in Burma. The two tribal groups that we became most familiar with were the Kachins and the Shans. The Kachins lived in the higher elevations of northern Burma. They lived by cultivating rice and they traded with the Shans. The Shans lived in settlements along river valleys in northern Burma. The Kachins were smiling hill people who were very friendly to the Americans. They helped the Americans because they expected that once the Japanese had been cleared out they would be able to live their lives as before. Some Kachins irregulars had assisted with the capture of Myitkyina and Kachin guerrilla forces worked with the Office of Strategic Services(OSS) behind the Japanese lines.Hundreds of redbrick pagodas and shrines, were scattered on the low lands along the Irrawaddy River. They always seemed more fascinating from a distance then when they were seen close-up. We were told that Buddhists had constructed the temples and shrines many centuries ago.An unusual sight for us was watching the Burmese women puffing on huge cigars, made of tobacco leaves and stems, and rolled in the cornhusks and tied with thread. They called these oversized cigars "cheroots."Most of the civilian homes and buildings in Myitkyina were destroyed in the battle to capture the town. Replacing them was a problem easily solved. Most homes were made of woven bamboo. It was not difficult to harvest an inexhaustible supply of bamboo from the jungle.The 1891st Engineer Aviation Battalion had constructed two airfields in northern Burma from October 1944 to March 1945. In April 1945 the 1891st Battalion was ordered to report to Kunming, China. Because we had participated in the India-Burma Campaign and in the battle of Northern Burma, all members of the battalion were authorized to wear two bronze battle stars on their Asiatic-Pacific Theater of War Ribbon.

Because China was so short of military supplies and equipment, higher headquarters made the decision that future units driving into China over the Burma Road would be issued additional trucks, in excess of their assigned vehicles, to drive over the Burma Road into China. The 1891st Engineer Aviation Battalion was given the mission of driving several hundred additional vehicles to Kunming when it was the ordered to report to China in April 1945. Most of us in the 1891st were very excited about our new assignment to China. I think we were all fantasizing about the beautiful Chinese women we knew we were about to meet. It should be explained that most young men, in 1945, including those in the military, regularly followed "Terry and the Pirates" in civilian and military papers."Terry" was a young pilot in China who was always running into beautiful women in his exploits in China.

The Chinese in Kunming did not all look alike. The half million people living in Kunming in 1945 represented a cross section of both free and occupied China. The merchants and businessman from the eastern provinces of China looked very different from the beggarly appearance of the native Kunming population. Attractiveprostitutes rode about the city in rickshaws casting glances toward prospective customers. Miao tribes-people, usually dressed in black, seemed to perform most of the menial work. Other non-Chinese residents were the shy, Lolo, tribesmen from the Tibetan border region and the French colonial soldiers who had walked out of French Indochina in 1940.

In late January we received our orders to board a ship in the Bay of Bengal. The ship's name was the Marine Panther. It was smaller than the General George Randall that carried us from Los Angeles to Bombay. Unfortunately, some of the living conditions on the Marine Panther were similar to those on the General George Randall. The bunks for the enlisted men were very crowded and were stacked five high. We still had saltwater showers and were served only two meals a day. The big positive difference was that we were allowed to remain on deck after dark. The reason, of course, there were no Japanese submarines searching for ships that might display lights at night. It felt so good to remain on the cool, dark deck rather than be confined to the crowded and noisy, below deck area. I found it fascinating to both gaze at the stars at night or to stare at the phosphorescence glowing in the black waters surrounding our ship. The Marine Panther did not stop until we arrived at Seattle, Washington in mid-February 1946.All of the soldiers on the Marine Panther were bussed to Fort Lewis, Washington. We received our final physical examinations. We were also issued new olive drab wool dress uniforms. All of our dress uniforms were taken from us when we were Camp Anza in August of 1944. I was a little surprised to discover that I had gained 35 pounds between the time I reported to Keesler Field, Mississippi in January of 1944 and my physical exam at Fort Lewis, Washington in February of 1946. The weight gain pleased me. I was really a very skinny kid in 1943; 6 feet, 4 inches tall and I only weighed 165 pounds.

TOP OF PAGE WALTER OREY'S CBI PHOTO ALBUM

COPYRIGHT © 2010 CARL W. WEIDENBURNER