|

|

By Maj. Thomas H. Moriarty

Air Service Command

ON THE budget books, a P-40 is listed at $50,000. In the air of Asia, that trusty fighter, still champion of them all for total victories against the enemy, could be listed at five hundred grand or five million dollars for that matter, depending on how many red balls of Japan were hanging in the sky over your airstrip or around your helpless transport as it flew toward the Hump.

There's one P-40 today that by ordinary figuring should be a debit of fifty grand, as it was the Air Service Command, expert in salvage, that beat the monsoon and multiplied the intrinsic value of the ship to ten or a hundred-fold.

It was late in spring when the monsoon broke unexpectedly over East Bengal. near the battlefields of Kohima. A pilot of Col. Phil Cochran's First Air Commando outfit was cruising in his P-40 when he ran into this fire-hose velocity rain and wind. The pilot streaked down for an emergency landing with wheels up.

In the drenching rain and violent wind, the pilot sat under his canopy for hours. Then the monsoon moved on and he saw the ship was mired in a rice paddy, more water and mud than earth. He hitched up his boots and climbed out, with the mission of reaching the nearest village and contacting the Indian police.

Photos by

LT. CHARLES W. DUNKIN

Air Service Command

In a short time Col. H. M. West, Jr., Commanding Officer of an Air Service Command "service group," received a telephone call. There was a fighting ship down on some uncharted spot. In the China-Burma-India Theater it was Air Service Command's job, along with airplane maintenance and aircraft supply, to find that ship and salvage it.

The Colonel called his trigger men on jungle salvage, Capt. N. R. McMartin of Fremont, Neb., and Capt. Charles L. Davis of Lakeland, Fla., his assistant. Then men rolled out the observation airplane and waved goodbye to Maj. Wayne L. Ramsey (Madison, Wis.), who was to follow with a detachment of ASC enlisted men. Each man a master short-cutter of precious repair time, a genius at improvisations.

|

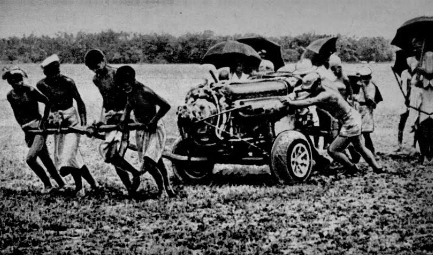

The engine removed from the P-40 is trundled over two miles of mud on a cart constructed from landing wheels of a salvaged airplane.

The engine removed from the P-40 is trundled over two miles of mud on a cart constructed from landing wheels of a salvaged airplane.

|

From the air, McMartin and Davis saw the P-40 was sunk in the paddy. There was not a road or trail near it. However, there was a stream about two miles from the ship. The captains decided to find a fairly dry bivouac spot adjacent and then, somehow, move the airplane out of its hole. The transportation problems were a specialty of Major Ramsey and his airmen.

Returning to their field, the men found Major Ramsey with a "mechanicommando" staff that included Lieut. Billy D. Prescott of Meridian, Idaho, Finance Officer, whose pouch was fat with rupees and annas to hire Indian coolies and rent river barges. Before long, miles had been negotiated and another ASC Command Post, typical of many river and jungle and mountain bivouacs, had been established "somewhere in India." Setting out across the mud with their tools, the detachment soon became a walking rescue party, knee-deep in mud and steaming. They found the plane "dug in," Cochran's pilot had been lucky, and only beautiful handling had kept the ship from bellying-over and burying him plenty deep.

"We'll take her engine out first," the major said. The ASC lads already were setting out the tools to loosen the power plant. The heavy engine offered a problem of leverage, with the soft mud not helping any. Bamboo poles, in the shape of an "A," were the answer for an engine hoist rigging.

|

In a little while the men heard the high-pitched chatter of natives. Their appearance was a welcome sight, for the coolies would be needed. However, the risk from curiosity was now present, so the detachment built a bamboo fence around the airplane. In addition to keeping the natives at a distance, the fence was a guard of sorts against wandering elephants, bullocks, or water buffalo.

On the first hoist-out of the engine, whacko! went the bamboo "A" frame. Too much weight. Another "A" frame was immediately constructed, reinforced, and a jack-of-all-trades cart, another ASC improvisation, was trundled over from camp. This cart was formerly the landing gear of another salvaged airplane. Its big tires are ideal for the oozy mud and long grass of India. With the cart's support, it remained only for the Indian coolies to pull on the ropes, with their leverage horizontally applied on a long bamboo pole, and work the heavy power plant across the thick mud to the river bank. A three hour job over a distance of two miles!

That night the monsoon fought back and the bunks in the swaying tent appeared ready to float out with the tired sleepers. Soon the flood roared so madly that the detachment had to retreat to a more solid windbreak.

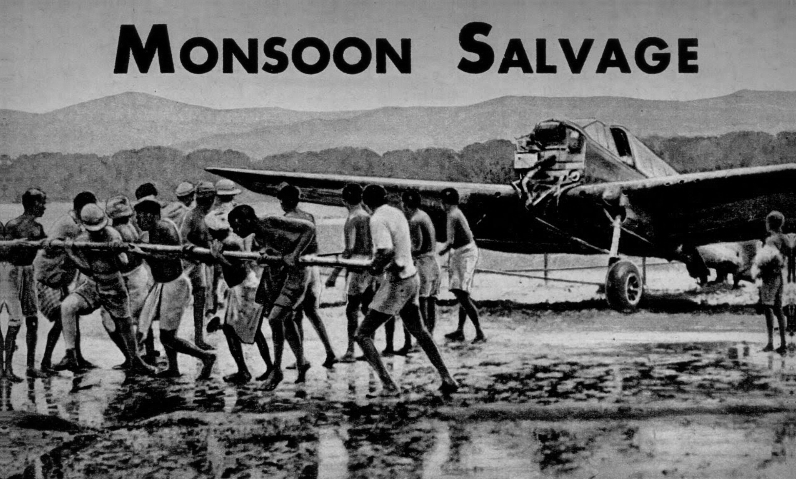

When they took up their job at dawn, the next move was to let the landing gear down, in order to use the buoyant wheels of the airplane to roll over the mud. This was accomplished by having a squadron of coolies lift the ship on their backs for sufficient seconds to permit the release mechanism to operate. Then a rope was attached to each wheel and tied to a horizontal bamboo pole. Coolie power, about twenty to a pole, pulled the airplane the tough two miles to the river in half a day.

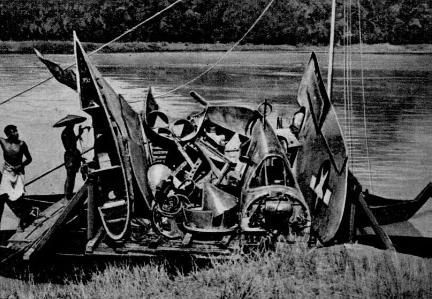

At the river bank, a barge was waiting. The P-40 was now taken apart, into small sections to fit the narrow barge. Wings had to be disassembled twice. Soon the detachment slung its tent, K rations, tools, and cart aboard, and settled down for the day and a half of jockeying through bamboo and banana trees and mud shoals.

At the rail head on the river, an Air Service Command truck and Service Group men were waiting. Ropes were attached to the airplane assemblies and the heavy objects winched up the slope by truck power, then hauled by truck to freight cars of the Indian railway system, to be transported back to the Service Group's headquarters.

Once at the Service Center, salvage of the P-40 became a rebuilding job for the mobile shop. From propeller lock-nut to rudder, every one of the thousands of working parts, including those of the engine, was checked, inspected, tested for battle efficiency. Through this "fourth echelon" (or heaviest) maintenance work, the P-40 took shape rapidly and one rainy morning, an ASC took her up. Diving her, split-S-ing her, throwing in a few chandelles, he satisfied himself that this fighter was "as good as new." A radio went to Col. Cochran's executive officer: "Mission accomplished."

Mechanics go to work on an extensive repair job on a big bomber at a Ninth Air Service Command station.

Mechanics go to work on an extensive repair job on a big bomber at a Ninth Air Service Command station.

|

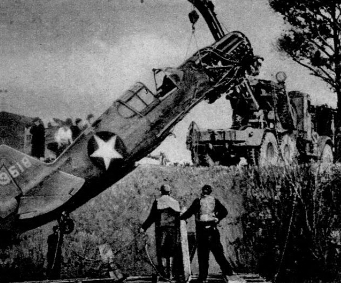

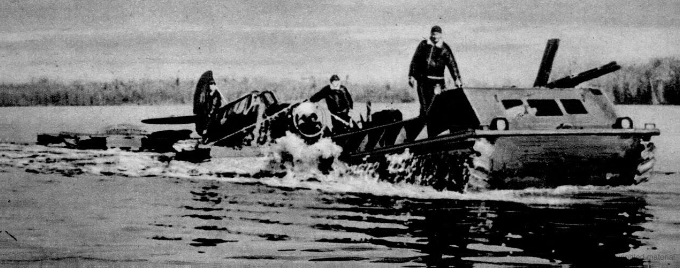

Salvage trucks (above) and boats (below) are called on to save whatever is left of a wrecked airplane.

Salvage trucks (above) and boats (below) are called on to save whatever is left of a wrecked airplane.

|

|

"We like to get 'em in good enough condition to make 'em flyable again," Colonel West commented. "Some are just too inaccessible to pull out like this one. If that happens, or if it's a wreck, we go in anyway with coolies and pack out all salvageable parts. Our boys are mighty proud of their 'keep 'em flying' job. They deserve all the praise in the world, and the fighter and bomber pilots are the first to give it to them. Air Service Command is part of a wonderful team, a real American team that guarantees victory."

FOR PRIVATE NON-COMMERCIAL EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY

TOP OF PAGE ABOUT THIS PAGE SEND COMMENTS

REMEMBERING THE FORGOTTEN THEATER OF WORLD WAR II

Visitors

What looks like a mass of junk, above, is the disassembled P-40 on a barge, ready for day and a half trip to railroad.

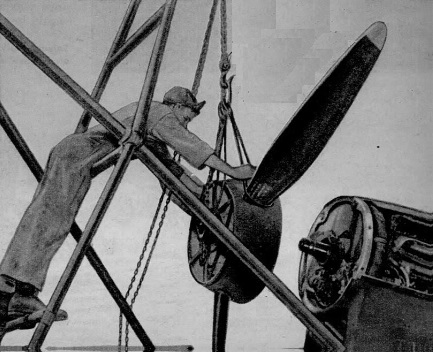

Below, aircraft repairman at Middle East air depot installs propeller on a P-47.

What looks like a mass of junk, above, is the disassembled P-40 on a barge, ready for day and a half trip to railroad.

Below, aircraft repairman at Middle East air depot installs propeller on a P-47.