This is the story of six English youths who, years later, found a new

Adventure on the Stilwell Road

by Adrian Cowells - Popular Mechanics - November 1957

|

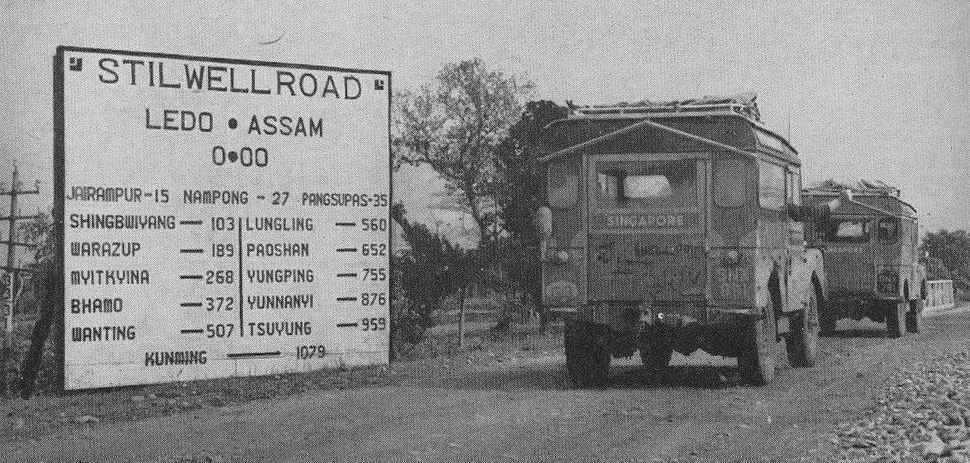

We were six graduates from Oxford and Cambridge, though with our beards, rainproof jackets and jungle boots there was little to connect us with an English university except the signs on our car doors. They read: "The Oxford and Cambridge Far Eastern Expedition." We had left England five months before and motored across Europe, the Middle East and India to our base camp at Assam. Singapore was our goal. We were trying to find an overland route across the span of Eurasia from London to Singapore.

Burma was the big obstacle, the one which had stopped everyone else. People said it was impossible; that the two war-time routes (the Stilwell and Imphal Roads) had been won for only a short period from the mud mires and craggy ranges of one of the world's most vicious jungle areas; that the roads had decayed under 10 years of encroaching jungle and monsoon rainfall.

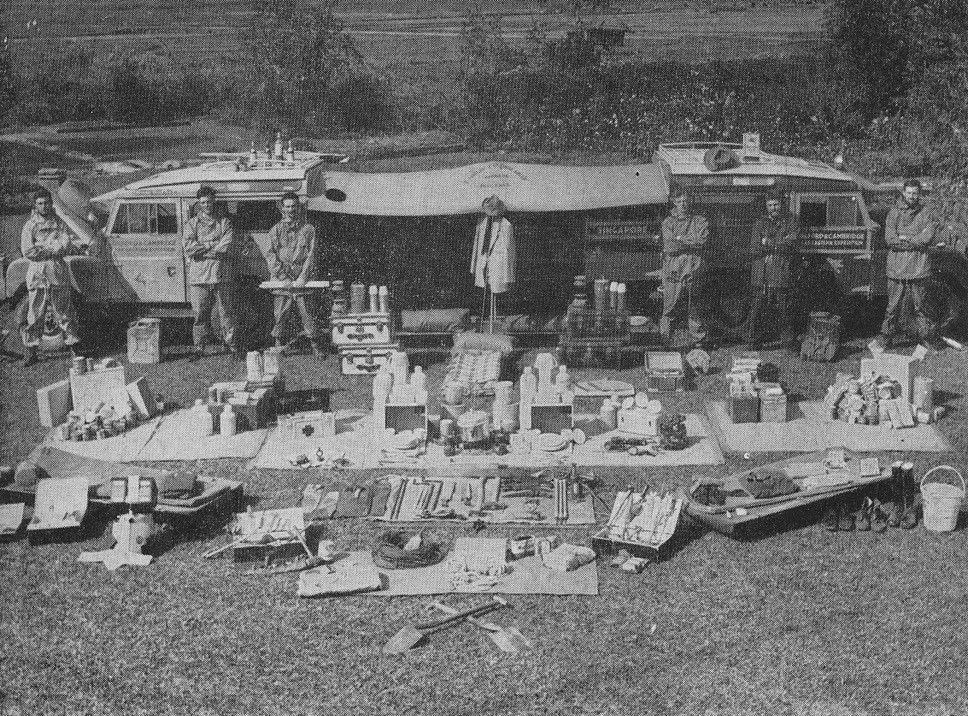

Included is bridge-building gear and sufficient food to last more than a month.

This was the first expedition given permission to make the trip in years. |

But we were not convinced. The Burmese government had given us overland visas, though they were granted "at your own risk." We had managed to get information on bandit positions. It might be true that no one knew anything about the routes into Burma, but we felt there was no harm in finding out for ourselves.

We had tents, camping gear and food to last more than a month; petrol tanks which would take us 1000 miles; power winches to pull the cars up a cliff or out of a river; equipment to build bridges; and two of the toughest four-wheel-drive, 10-gear vehicles in the world, our Landrovers.

And so, as we drank our coffee at the top of the pass, our escort told us what little was known of the road, and we told them what we had learned from conversations with former soldiers and engineers who, years before, had helped build it.

Japanese Invade Burma

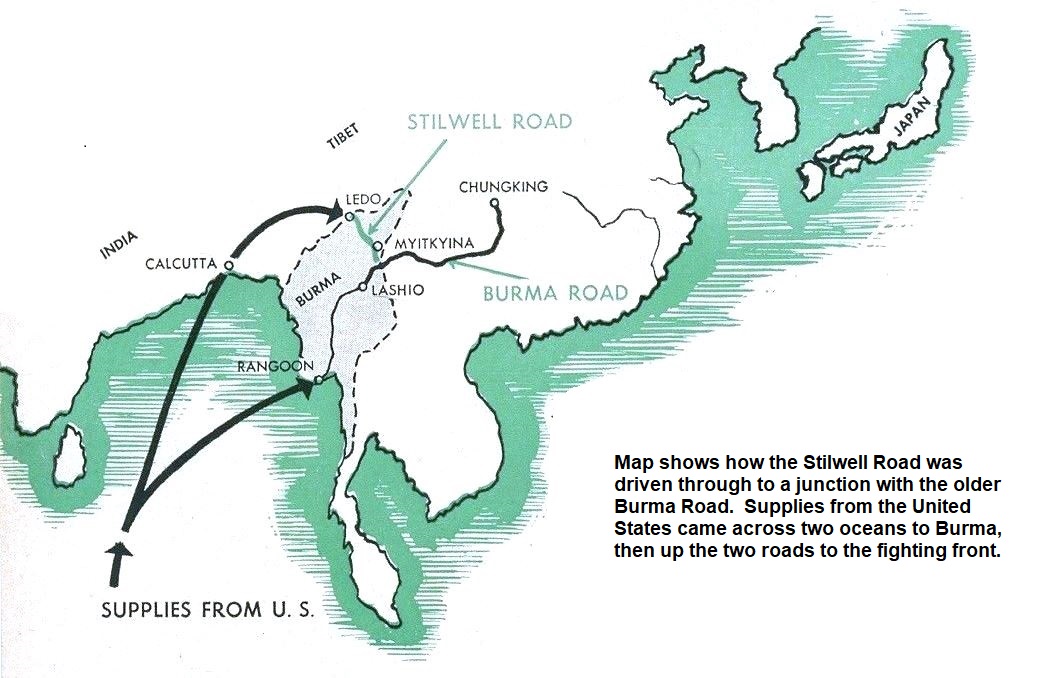

A week after Pearl Harbor the Japanese had invaded Burma and in a lightning campaign seized the Burma Road, drove a wedge between India and China and cut off Chiang Kai-shek from his supply line to America.

Some of the defeated British, Chinese and American forces in the north jettisoned their vehicles and retreated through the tangled morass of march and jungle which stretched between Myitkyina and India, staggered over the Patkai Hills into Hellgate. They had established the trail which was to become the Stilwell Road, but at that time men called it the "Road of Death."

One of the survivors was Lt. Gen. Joseph Stilwell. "I claim we got a hell of a beating," he said. "We got run out of Burma. I think we ought to go back and retake it." An army of millions of men under his charge was helpless until the supply line was established again.

Fantastic Engineering Project

To open the route he planned to blast a highway and oil pipeline from Assam to the old Burma Road. As an engineering project, to be carried out in the face of two Japanese divisions, it seemed fantastic. And because one man forced it into creation, it was named in his honor - the Stilwell Road.

The road was built by 10 engineer battalions behind a screen of jungle fighters. In that evil land, 200 inches of rain poured down each year, rivers rose 30 feet in a day. When Lord Louis Mountbatten flew over the route, he asked someone the name of the river below. "That's no river," said an American looking down at the sheet of water. "That's Stilwell's road." "Vinegar Joe" himself described it as "Rain, rain, rain, mud, mud, mud, typhus, malaria, dysentery, exhaustion, rotting feet, body sores."

In the mountains, landslides washed bulldozers into 1000-foot jungle chasms. A mule once sank right out of sight in the mud.

Mile-a-Day Progress

But the macadam moved inevitably forward. Men of all races, speaking 200 different dialects, struggled ahead thigh-deep in the mud. At a mile a day the road advanced. To build it, the Allies created the longest line of communication of the war - 12,000 miles across two oceans by pipe, rail or river steamer to Assam - and - when the highway was finally finished - by 1079 miles of jungle and mountain to Kunming.

To operate that thin macadam strip, 360,000 square miles had to be conquered at a great loss of human life.

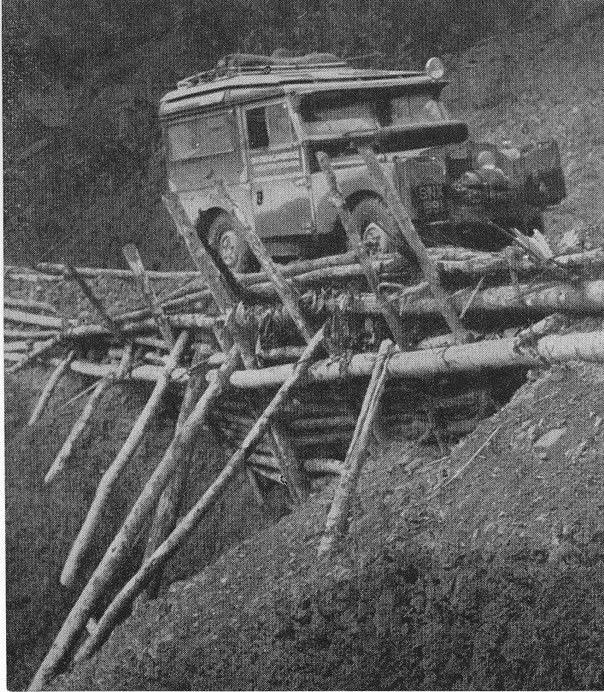

Torrential rains had swept away stretches of the road.

Torrential rains had swept away stretches of the road. Such sections had to be rebuilt with branches. |

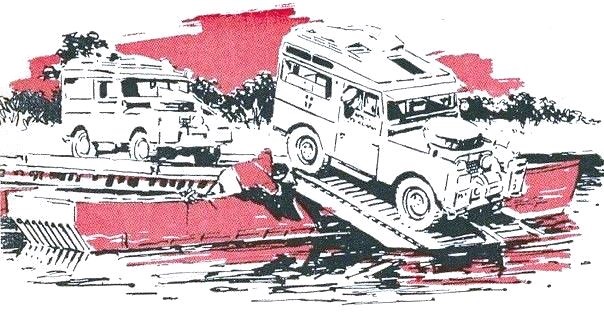

Washouts have swept away many sections. Expedition built bridges or forded streams up to floor level.

Washouts have swept away many sections. Expedition built bridges or forded streams up to floor level.

|

This was the ghost we had come to find.

We set out in silence as our escort bade farewell. The road was gone. What was left was a thinning undergrowth and stone foundations under the mud, mud which lined the track like grease on a garage floor. Our cars slithered between the narrow jungle walls. The track twisted and turned, clinging to the impossible contours of the mountainside, never straight for more than 30 yards. Occasionally we could see, 1000 feet below, the surly green of the jungle in a valley.

but they frequently went aground some distance from shore. |

Bridges Down

Soon we realized that our main problem was the streams of that mountainside. Some of the bridges were down, wood yellowed with rot, decaying into the water. Sometimes a Landrover stuck in the river bed, and water dashed in one door and out the other as we waded with winch and cable. Sometimes we came to an old Bailey bridge and laid logs across it to provide a surface. On occasion a whole span would sag under us.

But despite it all we descended by the second day into the bowl of the Upper Chindwin. That was our tribute to a great engineering feat: A road so well built that after years of neglect in that impossible environment it still survived. Naturally the macadam was gone, scrub encroaching, bridges swept away. But there was nothing which six men and Landrovers with power winches couldn't overcome.

As we came down into the valley we left the land of the Nagas (their last head-hunting war had been in 1952). We had been warned about them, but the few we saw were timid, small, cheerful and carried nothing but knives. Most of the other forest men had homemade muzzle-loading muskets or wartime rifles loaded with ammunition dated 1942. But none of them could have been more friendly.

All the way down the road we had been passing the ruins of war. We picked up a torn helmet from the upturned cab of a lorry. We poked inside a tank for snakes, and tried to identify the remains of enormous construction machines. There were stacks of oil drums, mounds of corrugated iron, skeletons of Jeeps and bulldozers. "Did you find any human skeletons?" is a question we are frequently asked. No, not a sign.

“Anyone for Badminton?”

We traveled down the red dirt until we crossed the river at Tanai, where we met our first representative of the Burmese government, a local district official in a lungyi (sarong). He concealed his surprise and refused to do anything so rude as to ask for our passports. "Would you like a game of badminton?" was all he said. We later learned from him that there was practically no traffic on the higher part of the road, though six trucks a year moved short distances between villages. He was surprised that it was possible to come from India.

We drove on next day through a forest valley, then passed Walawbum, Shadazup and Kamaing - names attached to nothing but a dozen huts in a jungle clearing and a memory of heavily fought battles. Then the valley disappeared and we entered Myitkyina, past the great airstrip which had been seized by Merrill's Marauders in one of the most successful jungle surprises of the war.

|

"Boy, oh boy! I sure am glad to see you!" were the first words we heard as we climbed out of the cars. A tall, smiling man came forward to pump our hands. "I sort of got left by the war," he said, and pointed at his "business," a wooden hut with mechanic's tools outside and, at a guess, a Burmese wife inside.

Huts Made of Trucks

In fact, most things in that part of Burma have been leftover by the war. Huts were made of upturned trucks, knives ground from car springs, and money earned by banditry with a wartime rifle. Transport was almost entirely by one of the 15,000 Jeeps and trucks the American army is said to have left behind, and I once saw a woman wearing Japanese epaulets hanging like rings from her ears.

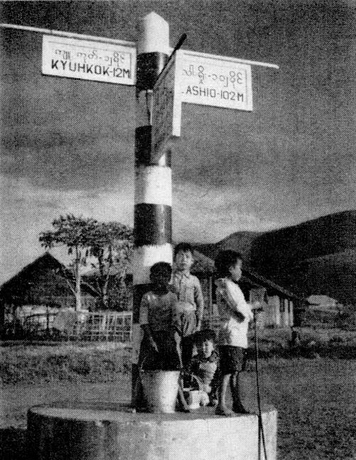

Children pose proudly on a signpost that marks one of the most important points of the war in Asia - the junction of the Stilwell Road and Burma Road

Children pose proudly on a signpost that marks one of the most important points of the war in Asia - the junction of the Stilwell Road and Burma Road

|

We left Myitkyina by a ferry constructed of two Bailey pontoons lashed together and powered by a homemade adaptation of a car engine. On the pontoon ferry was a lorry, in the lorry the band of some Kachin troops who refused to cross until they had played for us. Nine men with bamboo pipes, a drummer and a wild-eyed character who rhythmically beat a jungle knife against the lorry's metal side produced a weird, whimsical melody; all the more whimsical when we realized the tunes were Orientalized renderings of "Swanee River" and "Home Sweet Home," obviously picked up from U.S. troops. They smiled at our camera. They grinned bashfully at our tape recorder. They roared at their sergeant when he ordered them to move. They laughed at everything.

From there we began the mountain climb toward the junction with the Burma Road. It was a dramatic journey. The road climbed and turned like an Alpine racecourse, but instead of macadam there were dust and cobbles. We saw a few Jeeps and lorries on the road, the only vehicles that could manage it.

|

One morning we stopped at a village market while a couple of our men worked on the Landrovers. All manner of natives dressed in all kinds of costumes gaped at us. "Strange-looking Charlies," remarked one of our mechanics as he wiped a black hand across a dusty face, filthy shirt dangling over shaggy shorts, unbathed for a fortnight, the whole apparition crowned by a tufted beard and a disintegrating straw hat. I wonder what the natives were saying.

Mistaken for Missionaries

As we journeyed we found that, because of our black beards, we were frequently taken for Italian missionaries. We quickly corrected the mistake. A missionary had been shot by bandits only a month before.

One night our camp was a quarter mile from the Chinese border and we could see on the other side what we later learned was the "Flying Tigers" last airbase. Two of our men poled across the frontier river in a bamboo raft to have a look, landed in China, exchanged a few words with a passing peasant and returned to be "brainwashed" by the rest of us.

Finally one morning our dirt track came to a crossing, and the other road was made of macadam. We had come to the Burma Road, and the end of Stilwell's impossible engineering feat. On a signpost: Kunming 606 miles.

We had started our journey on the Stilwell Road partially to rediscover a wartime campaign. Instead, we found a smiling, delightful people. The tragedy we had expected lay not in the decay of the road, but in the impact of the war on a primitive people.

In a way, we were glad the highway had become a forgotten one.

|

FOR PRIVATE NON-COMMERCIAL EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY

Visitors

TOP OF PAGE ABOUT THIS PAGE SEND COMMENTS

SEE THE ORIGINAL ARTICLE ON GOOGLE BOOKS

REMEMBERING THE FORGOTTEN THEATER OF WORLD WAR II