Stilwell's Return to Burma

In December 1943, it could be truthfully said that never in history had Chinese troops launched a successful strategic offensive against a modern enemy. In the second Burma campaign, Stilwell proposed to rewrite history, staking his reputation on the unproven thesis that given proper equipment and training, Chinese soldiers were man for man, as good as any in the world. In his belief in Chinese values, Stilwell stood alone. Not only did the British and the overwhelming portion of the U.S. Army staff is Asia believe it was impossible for the Chinese to attack and destroy battle proven Japanese divisions of roughly equal strength in Northern Burma, the Chinese General Staff in Chungking held the same low opinion of its soldiers.

What Stilwell proposed do was this: to take raw troops, divorce them from the possibility of retreat, abandon fixed supply lines and make them dependent on air drops alone, drive them two hundred miles through jungle, swamp and mountains to conquer a skillful, entrenched and desperate enemy.

The bare outlines of the campaign were simple enough. The great objective was the open lowland of north-central Burma, where the meter-gauge railway wound its way through the linked towns of Mogaung and Myitkyina. If these two towns could be seized, a road might be built through the jungle from India to reach them, and then pushed on toward the Chinese border of Yunnan, to end the great land blockade.

No one spoke seriously of Myitkyina when the campaign was steaming up at Stilwell's headquarters on the Indian border in December, 1943. Myitkyina was a word, a phrase, a label on a dream that existed in Stilwell's mind alone. From the Allied position on the tangled mountain jungle border of India, the road to Myitkyina seemed incredibly distant. Ultimately, perhaps in 1945, it would be taken, but before then the campaign would have to proceed chunk by chunk in slow, plodding steps.

First there was the Tanai River to be cleared to make Shingbwiyang safe. Beyond the Tanai Valley lay the Hukawng Valley, studded with Japanese garrisons. Beyond the Hukawng lay the Jambu Bum hills and more Japs. Beyond the hills lay the Mogaung Valley. And beyond that 6,000 foot mountain range carpeted with jungle, was Myitkyina and its garrisons.

Stilwell had at his command two Chinese divisions - the 38th and 22nd - which had been moved from Ramgarh to the India-Burma border in 1943. In reserve, in Central India, another Chinese division had finished training.

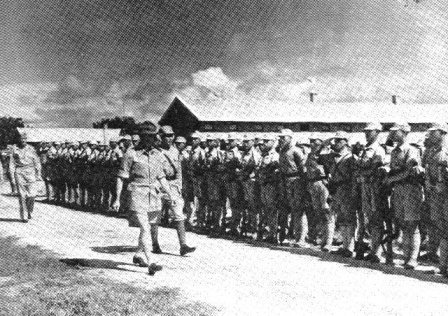

GENERAL STILWELL REVIEWS CHINESE TROOPS IN TRAINING

GENERAL STILWELL REVIEWS CHINESE TROOPS IN TRAINING

|

The main burden of combat rested directly on the Chinese divisions commanded by their own officers, but tightly subordinate to Stilwell's personal urge. The Chinese however, were only one strain in an association of races and nations that made the north Burma campaign of 1944 one of the war's great galleries of curiosities. In central Burma far to the south of the main drive, British commando forces under Wingate and Lentaigne operated. Kachin scouts, under American direction, raided Japanese outposts far and wide. The American combat force, Merrill's Marauders wheeled about the flanks of the main advance, unpinning each position the Japanese established against the Chinese by cutting around the jungle to their rear. The entire combat movement was superb in its strategic functions in an infantry war. Behind the Chinese troops crawled Ledo Road, struggling toward China. American engineers (Black and White), Chinese, Indians, Naga, built the road through the jungle and over the hills and under the treads of tanks and the wheels of the trucks that were carrying combat troops forward to clear the trace.

On the map, the campaign for north Burma was a line that wriggled tortuously from unpronounceable name to unpronounceable name. On the ground, it was rain, heat, mud and sickness. It was snakes in camp at night; K-rations and dried rice; snipers and ambush; darkness during the day and the rustling jungle at night. It was hike, kill, and die, or as Stilwell noted in his diary after one of his everyday marches through the muck, "Up the river, over the hogback - slip, struggle, curse and tumble."

Stilwell was in the jungle from January to July 1944, and for his personal participation in the campaign he was later severely criticized. He was at the time a three-star general of the United States Army and commander of a war theater, but he had abandoned his headquarters to command troops in the jungle.

PLANNING WITH CHINESE GENERALS

PLANNING WITH CHINESE GENERALS

|

Stilwell realized that for ultimate success in breaking the blockade, he would need a coordinated drive by the Y Force sallying out of Yunnan in the east under the direction of Brigadier General Dorn. He had been refused this cooperation in Chungking immediately after the Cairo Conference. He hoped to wring it out of Chiang's pride by the example of personal action and success in the field operations in north Burma. By word and courier, he kept up constant pressure on Chungking to commit its troops to action.

When in the last week of December 1943, Stilwell flew across the Hump armed with Chiang's vermillion seal of command, the Chinese 22nd Division of the Burma-India border had been skirmishing fitfully with Japanese outposts for months without success. Stilwell's first purpose was to force this division to take aggressive action, to blood it in battle by clearing the matted valley of the Tanai River. His first limited objectives were Taipha Ga and Yupbang Ga. By clearing these he would clear the area about the village of Shingbwiyang which he planned to make the base for his Hukawng Valley drive.

A cold trip across the Hump brought him to Assam from China, and from the air base the next morning he drove

by jeep over the rough new road trace reaching out of Ledo toward the jungle and Chinese combat headquarters.