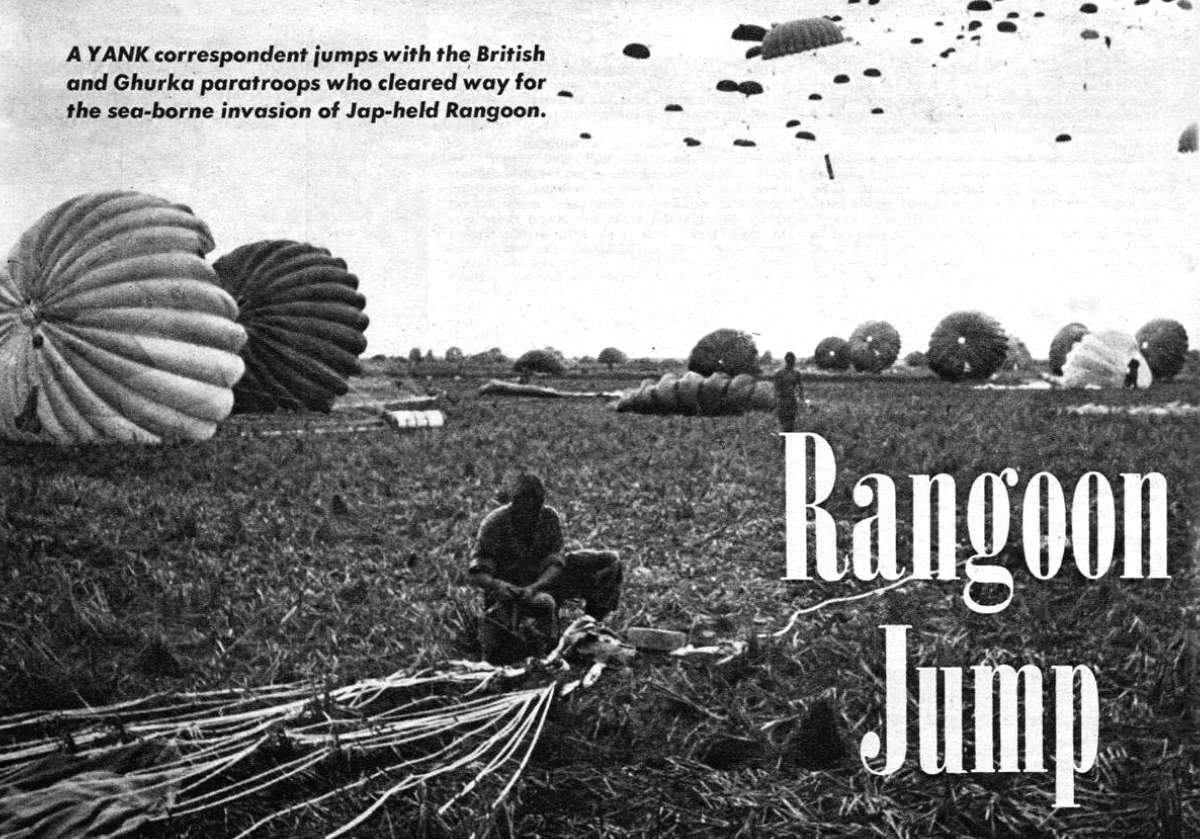

by Sgt. DAVE RICHARDSON - YANK Correspondent

Rangoon, Burma - The jumpmaster groped through the darkened C-47 to rouse you an hour before dawn. You opened your eyes as he offered you a cigarette and said, "One hour to go." He did it as matter-of-factly as though he were an ATC steward on the Calcutta-New Delhi run. Yet in a little while he would slap you out the door and you would take part in the paratroop operation that paved the way for the capture of Rangoon.

You were going to jump with the Pathfinders - 17 British Signals men and 20 Ghurkas who were to land 45 minutes ahead of the main body of paratroopers. They would prepare the way. Some would direct the other planes in by radio, others would mark out the drop zone with colored panels and smoke bombs. Still others would reconnoiter the vicinity of the drop to learn where the nearest Japs were.

There was little talking; you just eyed the other jumpers occasionally, exchanging wry grins. One of the tough little Ghurkas drew his kukri knife. He had trained with it since boyhood and back in his native Nepal he had used it to lop off the head of a cow with one deft stroke. Last year at Imphal he had done the same thing to some Japs in a night attack, He ran his finger along its gleaming edge, then replaced it in its sheath with a smile of satisfaction.

Beside you, a red-faced Scotsman took a final drag on his cigarette and murmured: "I've done 12 of the bloody jumps, laddy, and that makes this number 13, I'm always scared before every jump - we all are - but this time I'm skittish as a bloomin' bride. Number 13, mon!"

"Twenty minutes to go," you heard the jumpmaster yell as he switched on the overhead lights. "Put on your gear."

The plane was heaped with packs, rifles, radios and signal equipment, so the 20 of you bumped each other awkwardly as you stood up to fasten on your stuff. Then you lined up, holding the static-line fastener in your left hand. The assistant jumpmaster came up the line and locked each fastener to a cable stretched near the floor on the starboard side.

Standing there, as the minutes dragged by in the cramped cabin, you became bathed in sweat. Your shoulders began to ache under the tightly strapped 50 pounds of equipment and 20 pounds of chute. The plane was descending and slowing up to jump speed. Stooping down to get one last look out the window, you saw that the sky had brightened to gray dawn. Green paddy fields and thatched-roof villages had replaced the swampland below.

Then the jump bell rang. The jumpmaster shoved out three large parapacks, which were snapped away by the howling wind. The Number One man stepped to the door. He was a sandy-haired old sergeant who had told you he had made 49 jumps and was returning to Blighty in a few weeks.

The bell rang again. The jumpmaster yelled "Go!" and slammed the sergeant's back. The sergeant kicked out his right leg, hollering "Number One" and spun down and off into space. You shuffled forward in line, grasping the static line in your left hand, as man after man stepped to the door, yelled his number and kicked off.

". . . Number Five, Number Six, Number Seven . . ."

Your number was Ten in the 20-man stick. Your heart was pounding hard and your lips quivered. You felt weak and unsteady as you kept your eyes fixed to the parachuted back of the Number Nine man.

". . . Number Eight, Number Nine . . ."

In an instant you were facing the open door, sliding your static line down the cable. The Scotsman had caught his left leg just as he went out, forcing you to hesitate. But only for a fleeting moment. You got to the door, hollered "Number Ten" and kicked your right leg out into the howling wind as the jumpmaster slammed your back.

You closed your eyes just as you left the plane. But now that the wind had spun you around and you were hurtling feet first through space, you opened them. Everything was a blur. You wondered whether you would ever stop falling as the static line yanked the silk and then the shroud lines and then the risers off your back.

Then the little hunk of cord attaching the static line to the top of the chute snapped. The silk bellowed out. You were yanked up and, in a flash, sitting still. The chute was open. You lifted your eyes as you reached up for the risers. The big expanse of silk was a beautiful sight.

In contrast to the roar of the engines and the wind in the plane's cabin, now everything was quiet. You even heard a dog bark in the distance. There was no giddy sensation of height during this 700-foot ride earthward. You felt as though you were sitting on a hill looking down on the green rice paddies and patches of trees. You seemed to drift as slowly as a balloon. That is, until you got about 100 feet from the ground. Then you realized you had not been going slowly at all; the earth was rushing up to meet you. One moment you were watching it come up and the next - cu-rump - you were lying in the grass.

You lay there briefly after landing and even harbored the crazy thought that you could lie in that glorious grass for hours. But the sergeant was yelling at you: "Collapse that chute, quick!" You did and stood up.

No sprained ankles or broken bones, but you were wet and covered with mud. More mud was clogging the bore of your carbine. You reminded yourself that you'd better clear it as soon as you got into position on the perimeter.

At a half crouch you started walking toward the assembly area, which was located near a haystack a quarter-mile away. You glanced up and back to see the planes disappear in the distance and the other jumpers float down. Suddenly there was shouting in a village behind you. Spinning around and hitting the ground, you looked in that direction. But you got to your feet sheepishly, for it was only some Burmese people welcoming the men who had landed over there.

"It's the British!" screamed one Burmese farmer. "They're back! They're back!" All the other yelling was in Burmese, including the high-pitched voices of women and children. You remembered that it had been three long years since the Japs stormed into Rangoon.

In front of you one of the paratroopers was hobbling slowly and painfully. You caught up to him. he was the Scotsman who had premonitions about his thirteenth jump. "I've bloody well had it, all right," he grinned. "Sprained me ankle."

Arriving at the CP, you were assigned a spot on the perimeter. You lay down, took off your equipment and ran a patch through your mud-clogged carbine. Nearby the RAF signals team erected an antenna and soon were in contact with the other planes. Three men unrolled colored panels in the drop zone.

One of the British officers had taken the Ghurkas on a reconnaissance patrol of nearby villages. Soon one of his men appeared across the open paddy fields, trotting toward you. he handed you a message to deliver to the CP. As you carried it over, you read it.

"Tawkai Village unoccupied by Jap," it said. "Villages say no enemy between here and Elephant Point, but enemy dug in at point."

Getting back to your position, you unfolded your map and went over the parachute battalion's mission, as outlined in the previous day's briefing. The outfit was to land on D-minus-one about 25 miles south of Rangoon and then clear all Japs from Elephant Point, at the entrance to the Rangoon River. This would allow the seaborne invasion of Rangoon to pass up the river on D-Day.

You were now six miles from the point and there was estimated to be between a company and a battalion of Japs manning shore defenses there. That meant the paratroopers would have to work fast in getting to and taking their objective. If it wasn't taken by sundown, the Japs could hold it all night and give a pasting to the landing craft at dawn.

Nearby, one of the Pathfinders let out a shout. "Here they come!" he said. "Look at 'em - what a bloomin' armada!" In the distance the sky was dotted with little specks that came nearer with an increasing drone. Now you could make out the C-47s of the Combat Cargo Task Force - 40 of them, flying in threes, one group behind another like a parade. British and American fighters scooted back and forth on all sides of the C-47s. Light bombers buzzed the thatched-roof villages and clumps of brush, looking hungrily for targets. On the ground the Pathfinders lit smoke bombs to give wind direction.

Now the C-47s were overhead. Craning your neck, you saw little black objects spill out of their doors, plummet down and then blossom chutes. You looked closely to see which were men and which equipment. The way you spotted the men was by their dangling limbs. One or two of the black objects never sprouted chutes - they just angled earthward. You watched these closely and breathlessly until you discovered that none of them had limbs. Apparently every personnel chute had opened.

Within an hour the paratroops were fanned out in skirmish lines, plodding through ankle-deep mud across the broad paddy fields toward Elephant Point. The point and flanked platoons carried orange umbrellas to mark the advance for the supporting fighter-bombers.

About mid-morning the sun broke through and an elaborate bombing schedule got under way. Lumbering B-24s of Eastern Air Command, some American and some RAF, thundered over to lay sticks of bombs on the point. Several fires were started. For three hours the Liberators bombed, with B-25s and Mosquitoes streaking in between flights to bomb and strafe.

By mid-afternoon, one and one-half miles from the point, you passed through villages that had taken some of the heaviest bombing. Incendiary bombs had sparked the bamboo and grass huts as though they were cellophane. Now they were nothing but smoking embers. The inhabitants, some terrified and shaken, streamed back. They said some Japs were headed your way. Although there were Jap ack-ack emplacements all over the place, none of them showed signs of having been occupied for some time.

And then the forward platoon bumped the Japs.

The lieutenant colonel in charge of the battalion heard about it over his handie-talkie. He casually twirled his eight-inch red mustache and then gave brief orders. "Set the three-inch mortars up," he said, "and put smoke shells on those bunkers up there. We'll call for fighter support." He pointed to some high mounds that looked like pyramids about three-quarters of a mile away. The RAF air-ground radio team contacted the planes and as soon as the bunkers had been marked by smoke shells, fighters roared in to bomb and strafe. This went on for half an hour. Then the forward platoon radioed that the remaining Japs had beat it, so the battalion pushed on - a bit more cautiously now, for this was the last mile to the point.

The bunkers, you discovered upon reaching them, had been constructed so long ago that they were overgrown with grass and looked like hills. But there was no other high ground in the vicinity, so they stood out like sore thumbs. Each bunker had an interior of heavy wooden planking and slits for machine guns. Near them were freshly dug foxholes. Beside you a stolid-faced Ghurka straitened the ends of the cotter pins in his grenades, readying them for quick pulling.

The forward company, which you were traveling with now, got to a series of bunkers only 600 yards from the point when a sniper's bullet whined overhead. More shots followed. Everyone ducked for cover. A Ghurka grabbed your arm and pointed. There, in plain view 200 yards away, were some figures walking among beached landing barges and bunkers. A Ghurka Bren gunner opened up. The figures started running. The whole company began shooting. Once more the three-inch mortar was brought up and the fighters dove in. For some reason the Japs refused to take cover; they kept running from barge to bunker across open ground.

"Must be bomb-happy," said a captain. "In three months at Imphal and Kohima last year I only saw two Japs who exposed themselves."

Under covering fire the Ghurkas began to run and squirm up on the Japs. But before they could get to within 100 yards of them, the Japs disappeared. The place we had seen them was north of Elephant Point. The company commander put his glasses on the point for a few moments, then decided to slip his company south of the Japs to get to the point while another company occupied them with plenty of firing.

You moved the last 600 yards with ready rifle as the company skirted bomb craters, peered into bunkers and frisked bushes. Before you knew it, you were walking up to a Jap radar tower and realizing that the water 30 yards on the other side of it was the Rangoon River. You had reached the objective - but the fighting was not over.

The point, like the previous villages, was a maze of bomb craters. It contained little besides the radar tower, two shrapnel-shattered bungalows, a few gun emplacements and a half-dozen bunkers. "I reckon," said a Britisher, "that the Jap threw all his radar equipment and shore-defense guns in the drink."

Then the Japs started firing again. There was Nambu fire this time, crackling in short bursts. And again the Japs started coming out into the open. Other paratroop companies moved up and filtered into positions between the point and the Japs. The firing increased on both sides. A flame-thrower was brought up to silence the machine gun in one of the bunkers, but the ground was too open to get it near enough. A British officer and two Ghurkas crawled up with grenades. When within 10 yards of the Nambu they popped to their feet to attack the slit it was firing from. The officer was killed and one of the Ghurkas wounded. They had succeeded, however, in forcing the Japs out, and a heavy Vickers machine gun caught them as they ran out the back.

Snipers' bullets were pinging all over the place. A big steel landing barge on the beach 200 yards inshore seemed to be the Japs CP, so mortar fire was put on it. Just then a flight of C-47s with fighter escort started circling to drop supplies to the rear company. The air-ground radio team borrowed the fighters to thoroughly strafe the Jap barge until it was aflame from stem to stern. It burned brightly all night.

"Looks like it's going to be a nice quiet evening," grinned a sergeant. There were Japs on three sides of the perimeter, with the river on the other side. You had wondered why there had been no Japs on the point, but now you began to feel uneasily that it had been a trap. The firing finally tapered off to scattered shots now and then, but everyone expected a counter-attack during the night.

Too tired to dig in, you curled up in your ground sheet in a bomb crater. The attack never came that night, but the rain did. Torrents of it came down from midnight until dawn. You took cover in a bunker with nine other men, trying to sleep sitting up but instead managing only to sweat it out and ache.

Some villagers came in the morning and said the Japs had pulled out during the night. They said there had been only about 50 of them near the point, that the rest had left in barges the night before we arrived, after hearing the British were driving into Rangoon down the road from Mandalay.

Suddenly a shout went up. Everyone ran to the crest of a sand dune and looked. It was the D-Day convoy. The landing craft chugged up the channel and swung past a buoy 300 yards offshore. The paratroopers hollered "Good luck," and some of the men on the boats waved back. When some of the LCAs stopped at the point on the way out to pick up paratroop casualties, you went with them. Rangoon, the last big Jap base in Burma fell to the British the following day.

|

Rangoon Jump

by Sgt. DAVE RICHARDSON

Adapted from the July 1, 1945 Continental Edition

YANK - The Army Weekly

VIEW ORIGINAL PAGES

TOP OF PAGE ABOUT THIS PAGE

CLOSE THIS WINDOW

Copyright © 2005 Carl Warren Weidenburner