|

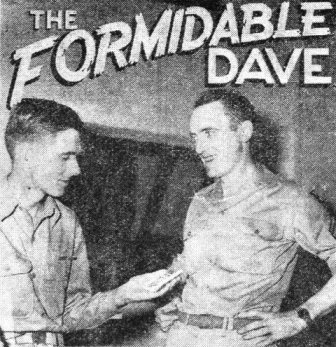

Richardson was one of two servicemen who were put on the list, the others being civilians. In the picture he is wearing the Legion of Merit, awarded to him by Gen. Douglas MacArthur. Dave is currently covering Burma for Yank. |

If you haven't met him yet, we introduce to you T/Sgt. Dave Richardson, Yank's senior staff correspondent

in the India-Burma and China Theaters. He is by far the best known and most popular G.I. this side and beyond The Hump.

A tall, lean young man with a long stride, his face is lathered with freckles, his eyes are blue and his

hair is flaming red. His candid camera hangs from his neck like an admiral's binoculars and he wears fatigues even at a

general's cocktail party. Dave's fatigues, by the way, are made of the dressy sea-green poplin used in this Theater exclusively

for the Mars Task Force.

Only during his rare visits to Calcutta does the soldier correspondent don khaki. Then he trims his snappy

little mustache, pins up his Legion of Merit, his Combat Infantryman's Badge and the six stars of his Theater ribbons.

He is the soldier's correspondent right out of the book.

VOIDS ORNAMENTS

Dave's favorite hunting ground at present is Burma. Where things happen he stands in a lake of war and

scribes like a rocky isle. He is not necessarily an outstanding writer. There is little beauty in Richardson's style.

He avoids ornaments, ignoring the beauty of the passing scene. He writes

consciously for the G.I. audience of personal

experiences. Soldiering is his second nature and war to him is no adventure. It's a job.

As a civilian he liked to read fantastic accounts of heroic exploits. As a soldier, and all soldiers feel

alike, his soul revolts when the grim business of fighting men is glamorized or exaggerated. The sources of his stories

rest in the fact that they are not mere eye-witness accounts but battle reports of a combatant.

WAIST GUNNER

You can ride a breathtaking night mission, but Dave will top the bill by acting as a waist gunner in the

plane he rides for copy. The same goes for tank battles. He is a turret gunner when he covers a tank action. As an

Infantryman he is beyond competition as far as correspondents go. "Red" Richardson not only outhikes anyone but commands

a private intelligence collecting agency, supplied by Americans, Kachins, British, Chinese and Burmans who see the war

from the foxholes.

When the siege of an enemy garrison begins, Dave hurries into the field, contacts his agents and draws

his own conclusions as to the collapse of the garrison. If he concludes it is the case of a suicide garrison, he hurries

into another assignment and returns to the spot a month or two later. And the R.I.C.A. (Richardson's Intelligence

Collection Agency) seldom errs. It was uncannily accurate about the so often ill-predicted collapse of Bhamo.

Dave became what he is partly through the steel and fire of the Southwest Pacific and the Burma War,

but mainly through his own conquest of life, a hard youth which was bold and very American.

As a high school boy in South Orange, N.J., he supplied the local Daily Courier with a weekly

roundup of school news. During the first six months for no baksheesh at all. In the second year the baby

columnist averaged two bucks a week.

WORKED WAY

David Bacon Richardson had to work himself through three fourths of his four years at Indiana University.

During the first summer he was a garage mechanic, the second year a ledger clerk and in the third a junior draftsman for

the city of Newark. He was going to become an aeronautical engineer, but the bug got him when he was editing the

Indiana Daily Student, which calls itself the largest college daily in the world. Student editor Richardson

worked 10 hours a day. He also was the editor and proof reader of the college football program, janitor in the men's

dormitory, press agent for a night club in Bloomington and table waiter in his fraternity house. After graduation they

awarded him a silver cup on the basis of "character, scholarship and journalistic promise." Ernie Pyle once received the

cup. Now that Wendell Wilkie is dead, Pyle is the school's most famous alumnus.

HATES FASHION

Richardson nourished an attitude in those years, an attitude towards life which became the leitmotif

of his war years. he declined, for instance, to attend a fashionable Eastern college. "I hate snobs," said David and

went to the Midwest. "I hate snobs," he said again, when he was pressed by friends to join a fraternity in his junior

year. Like Willkie, he joined one in his senior years.

After college, Richardson was hired by the New York Herald Tribune, was transferred from copy

reader to sportswriter. The Tribune was going to send him overseas, but the greetings of his President landed

him instead at Camp Pendleton, W.Va. There, David Bacon Richardson dropped his elegant name and became Pvt. Dave

Richardson, photographic editor of the camp paper. With a fifteen buck Argus camera he made himself his own photo-reporter.

Some of his features were reprinted in Life, Pic and distributed

nationwide by the Associated Press.

Most successful was his photo reportage of a gracious Negro lady who brought fresh doughnuts and hot coffee every night

to weary coast artillery men, guarding barb-wired Virginia Beach against German submarines.

The war was young when Dave Richardson, then a corporal and public relations man of his coast artillery

unit, used to visit his girl in Washington. During one of these sojourns he dropped in at Army Public Relations and

proposed a soldier's magazine. But a magazine was already in the making, Yank. Dave was considered with four

thousand other applicants. Six weeks later Dave was on his way to Gen. Douglas MacArthur's command.

Sad of heart, with a cable in his pocket announcing the sudden death of his father, war correspondent

Richardson arrived in New Guinea one sultry December morning - just in time to make the battle of Buna. He wanted to

go to the front right away, but having never been with Infantry before, he had no idea how a front looked. He walked

15 miles in search of it, always asking passing G.I.'s for the direction.

WHERE'S FRONT

"Where's the front? he asked for the last time. "This is the front. If you walk 15 more yards, you'll

get your head blown off."

"Can I stay with you?"

"You'll have to get a hole."

"Have you a spare hole?"

At last he found a spare hole in the depth of the jungle. It was fairly large and two were in it

already. Richardson crept in, sandwiched himself in between, and fell asleep. When he woke in the morning he found

the two Americans in his foxhole stiff and dead, killed the day before.

The jungle was so thick you couldn't see the Japanese in front of you. But you could hear them talk.

Dave spent the day after the rude awakening at the forward OP, only 30 yards from enemy positions. Dead Japs lay all

around, smelling badly, while the news man dined on his rations. Richardson looked for a man who could teach him the

rules of the battle jungle. He found on in the person of a Sioux Indian scout. They spent the following night in a

two-man foxhole.

SIOUX SCOUT

The correspondent and the scout divided the night between themselves, one would watch while the other

rested. With a grenade in one hand, his fingers tightly around the spring, Dave gazed into the darkness. A slight relaxation

would have softened his grip around the spring and burst the grenade. Two hours passed, the grenade changed hands several

times.

During the exacting vigil the Indian spoke about his wife, his child and the tailor shop he would open

after the war. And something passed there between the two men, something difficult to grasp, something that has made

so many soldiers in this war think and wonder. The mutual understanding between the two men

traveled decades in hours.

They were very old friends by morning, when a sergeant came to their hole to send the Indian on patrol.

later in the day Dave leaned over the stretcher of a dying man whose stomach was blown wide open. The

wounded man's eyes were glassy and he could recognize no one. He was the Sioux Indian.

It is not always the hard blow of a singular event that breaks or makes a man. The dull pain of a cruel

atmosphere kills or steels just as well. On Buna Beach, Richardson lived in the worst malaria pesthole of the world.

Ninety-four per cent of the men were stricken with the plague. Dave slept with them in the swamps, his whole body

shriveled up, covered with tropical ulcers. On a four months tour during which he visited every American outfit in

New Guinea, Richardson became so weak of exhaustion, yellow jaundice and anemic dysentery that he was unable to eat

and had to be fed through his veins with sugar water.

Well again, he went up with MacArthur's first amphibious invasion to the Solomon Sea; he was the first

correspondent to raid with Lt. Bulkley manning a machine gun on a PT boat, and the first American to enter Lae and other

Japanese strongholds. You will read about these exploits in Dave's own book, the soldier correspondent is preparing

on his life in the field.

The young man who came to the CBI a year ago was a different Dave Richardson from the correspondent

who went to Australia in 1942. Now, he was a soldier first, correspondent next. His outlook had narrowed, his concern

in the warring world limited itself to the general interest of the average G.I. he identified himself completely with

the men for whom he was writing. His readers in this Theater will remember him mainly for his spectacular coverage

of the first Burma campaign.

MARAUDER

Dave was one of the four war correspondents allowed to join the Marauders and the only one to stick it out

to the last. Two dropped out at the end of the 150 miles on the Ledo Road, the third correspondent, Frank Hewlitt,

left after the first battle because he was unable to get out his copy otherwise. Dave stayed with the outfit until

May and went out only while the Marauders were resting.

Richardson had two weeks for himself until he could rejoin Merrill's men. He used the fortnight to cover

Colonel Rothwell Brown's famous tank battle of Inkangahtawng in the Hukawng Valley. It was Dave's first tank battle,

but he manned a machine gun inside one of the rolling tanks.

After the battle of Inkangahtawng, Richardson hurried back to the Marauders for the battle of Myitkyina.

He wanted to be the first correspondent to enter the town, but 8,900 men were ahead of

him as he was trying to catch up

with the forward columns. The soldier correspondent walked 71 miles in three days through muddy, difficult jungle

terrain. Yet, in spite of the effort, he was the last correspondent to reach the Myitkyina airstrip.

It was a fiasco Dave never regretted, for his name became a legend thereafter among the fighting men.

He was no longer a visitor who comes and sees and reports. He was one of them.

Adapted from the March 15, 1945 issue.

Original issue of India-Burma Theater Roundup shared by CBI veteran Tom Miller

Copyright © 2006 Carl Warren Weidenburner

MORE ABOUT DAVE RICHARDSON

TOP OF PAGE PRINT THIS PAGE ABOUT THIS PAGE SEND COMMENTS

CLOSE THIS WINDOW