Scroll down to view...

|

The greatest combined onslaught in the history of the northern Burma war was in the making on the 32d day of the siege of the city - but it never came off. The Japs turned chicken and ran. BHAMO, NORTHERN BURMA - Probably the saddest sacks in the vicinity of this shattered city following its sudden collapse were the GIs and pings of the Chinese-American Composite Tank Unit. "It was a dirty trick, that's what it was," griped the driver of a General Sherman. "We travel hundreds of miles over dusty roads to get here, and what happens? The Japs turn chicken on us and shag out of the place the night before we arrive. We never even got to fire a shot." That's one way of saying that the fall of Bhamo, largest city ever taken by Allied forces driving through northern Burma to reopen the land route to China, was so sudden that it took everybody from private to general by surprise. The city had been bypassed weeks before by Chinese and American outfits pushing on as far as 50 miles southeast toward the Burma Road. It had been encircled by a gradually tightening ring of Chinese troops, and pounded day after day by fighter-bombers and mortars and artillery. Yet its Jap defenders - a "suicide garrison," the communiqu s called them - continued to hold out stubbornly, fighting for every yard they gave up and tying up troops and weapons that were needed for the final 100-mile break-through to China. There was no sign of a sudden attack. Then the Chinese-American tanks began to rumble down the Ledo Road. They hadn't been used in Burma since the monsoons bogged them down six months before. Seeing them, GIs in Engineer, Signal and Quartermaster outfits along the way figured something was up and it was. A big attack was being hatched to spring on the 32d day of the siege - an attack so big it would be the greatest combined onslaught in the history of the northern Burma war. Besides the tanks, 105 and 155-mm howitzers were brought to the outskirts of the city. Tenth Air Force got ready by bombing up every available P-47 and B-25. The Chinese 38th Division surrounding Bhamo prepared to move in under the bombing and the barrage, behind the tanks. Everything was set by dusk of the night before.

But the big attack never came off. It didn't have to, because the Japs bowed out. About midnight they suddenly concentrated everything from machine guns to artillery on the southern outskirts of the city. Then they took two days' rations, went to the south end of Bhamo and either sneaked into the jungle there, or slipped down the bank of the Irrawaddy River and tried to float on rafts or swim to safety. Some of the Japs managed to get away under cover of darkness, but the Chinese had a field day with the rest of them. As they raced across the beach or bobbed in the current or blundered through the jungle, Chinese machine gunners along the river bank and south of the city mowed them down. This went on all night and up until noon the next day, as the Chinese crowded in behind them and caught the last bunch of them just on the edge of the river bank. By 1400 hours, Bhamo was quiet enough to be considered taken. Two hours later I entered the city with a group of Americans escorted by Chinese officers. A mile from the center of town two Chinese tommy-gunners barred our path, jabbering and pointing down the road. A Chinese colonel with us exchanged a few words with them and then turned and said: "It's all right for us to go in, but they say we should be very cautious. They say there are still a few snipers, a lot of mines and some booby traps." With that, we walked past the last mile post on the tar road into Bhamo. Grinning Chinese soldiers passed us in twos and threes, laden down with stacks of bayoneted Jap rifles and Jap equipment. Soon the road became obscured by dirt and rubble, forcing us to step gingerly, for every square acre of the rolling plain seemed to be pocked with bomb crater and shell and mortar holes. In many areas the earth was churned up as thoroughly as though it had been gone over with a huge plow. Just as we passed two bullet-riddled trucks that lay toppled in a 500-pound bomb crater, the crackle of a Nambu light machine gun echoed across the countryside from several hundred yards away. Following it came the heavier rattle of a Chinese water-cooled gun. "Guess they're right about there still being Jap snipers," said an American captain behind me. "Some of these babies must still want to die for the Emperor." Our single file column spread out a little after that - just for safety's sake. The charred remains of houses were everywhere. Some were nothing but skeletons of fire-blackened beams. Some had burned to the ground with their corrugated tin roofs half-covering the ashes. Others had been ripped apart and splintered by artillery and bombing. Only a few escaped the marks of battle. Trudging past a clump of trees beside the road, we noticed a smashed Jap tankette. Its turret had been blown off, its front bashed in and one of its treads had come partly off and now lay curved across the ground like a giant snake. Seeing it, a Chinese interpreter said: "We got that with a bazooka two days ago." In the sky above it, a hundred feet away, was the towering white dome of a stone pagoda, chipped and bruised by cross-fire. The familiar stench of dead Japs filled the air at irregular intervals along the way. As we passed each body, we

None of these Japs had been killed neatly, by a single bullet or shell fragment. Most of them were badly smashed up, like the one with his head blown off, the one without a leg or arm and the one who lost most of his stomach. "It may take our men a lot of ammunition to kill a Jap," said the Chinese colonel. "But when they kill one, he really looks it." Nearing the main part of the city, we passed two and three-story stone and brick buildings. In various stages of shambles, they looked much like the buildings we had seen in newsreels of the bombing of Britain or the battle of Cassino. Furniture and household belongings were scattered in and around them. Piles of brick and stone surrounded them all. One structure was nothing but a doorway and a pile of thousands of bricks. Inside another building was a Japanese 75-mm field piece, with its muzzle blown off. Here and there, everywhere we went, were OWI and Psychological Warfare leaflets that had been dropped in Bhamo by American planes during the siege. On the leaflets were photographs of Jap prisoners receiving kind treatment in Allied hands, maps showing hoe Bhamo was surrounded and bypassed and in big yellow letters against a red background the single word "Surrender." "These leaflets have worked occasionally in other battles," said the Chinese interpreter, "but they didn't here. The only prisoners taken in the entire battle either were too weak and bomb-happy to resist, or were captured by surprise. One of them said they had used the 'Surrender' leaflets to build fire with." From the looks of things, the Japs had fought from all kinds of positions. We passed elaborate trench systems, pillboxes constructed of teakwood 18 inches thick, rat-like holes along the sides of buildings and tanks that had been used solely as pillboxes. Along the shore road, where the Japs fought their last rear guard action before darting for the river, large stores of small arms ammunition were stored in holes. Every trench or emplacement seemed to have an escape route to the

In the northern part of the city, where the bitterest fighting of the siege had taken place, a huge red brick jailhouse had been the keystone of the Jap defenses. Inspecting it with another party of Americans next morning, I could see why. It was several feet thick and from its high walls the fields of fire could command three hundred yards of relatively open ground in any direction. Two big chunks of the solid brick wall had been knocked out by bombs. More than 50 bomb craters around it had been used as trenches by both the Japs and the Chinese who had dug into them and barricaded parts of them. Dozens of tank traps had been laid by the Japs at every possible entrance to the city. There usually were either rows of deep holes that had been camouflaged with brush or they were barriers of pipes, wire, wood or stone. The Japs must also have feared glider landings, for they dotted the only big field in Bhamo with oil drums spaced at regular intervals. They used these oil drums for many of their emplacements and road barriers, too. Several times during our tour we passed Chinese engineers with mine detectors methodically combing each road. In some places we saw the results of their work - piles of mines dug up and stacked beside the road. Now and then, Chinese soldiers came jogging along with twin loads of dried fish on either end of bamboo poles balanced on their shoulders "Zippon," they grinned as they saw us looking at the fish. That's their pronunciation of Nipponese and fish weren't all they had discovered in Jap ration dumps. Little groups of them squatted all over the city, enjoying steaming bowls of Jap rice which they ate with fast-moving chopsticks. The Chinese love to exhibit captured Japanese weapons and equipment. There were more than half a dozen of these exhibits in various prominent places. In each exhibit were dozens of helmets, stacks of Arisaka rifles, crates of

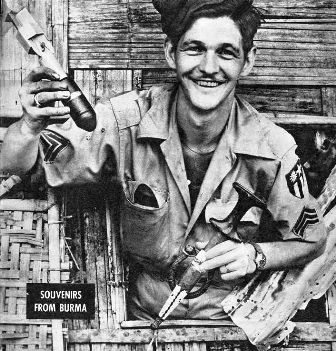

And now that GIs had started streaming in, brisk trade for battle souvenirs had began, with groups of Chinese and Americans gesturing and bickering each in his own language for such items as Jap flags and rifles and sabers. After more than a year of close association with GIs while fighting in Burma, the pings of the Chinese 38th Division have become pretty sharp bargainers. They usually hold out for several cartons of American cigarettes or a flashlight or cigarette lighter in exchange for their booty. A group of soldiers were clustered in the middle of the road near the old printing office. We stopped and edged in. The object of their curiosity was a wounded Jap prisoner on a litter, shivering with fear and avoiding all eyes. Nearby, a Chinese soldier pointed out three Jap bodies near a bunker. He explained by gestures that all of them were suicides. They had taken a grenade a piece, tapped it on their helmets and then held it to their chests or stomachs. Each of them were minus his right arm and either most of his chest or most of his stomach. There wasn't a Burmese civilian in the place, the first 24 hours after Bhamo fell. They had all fled into surrounding villages weeks before at the approach of Allied troops, to avoid the dangers of battle. And except for a few hundred Chinese and Americans in the once flourishing trade center of 8,000 people, the whole city now possessed the empty quiet of a ghost town. As we started to leave Bhamo, I happened to stumble upon an amazing little discovery. On the ground with several articles of Jap clothing out of a barracks, I spotted a magazine. Picking it up, I found to my surprise that it was a copy of Newsweek, dated Aug. 4, 1941. That was four months and three days before Pearl Harbor. The Japs must have got the magazine from among the belongings of some American who had fled from Bhamo when they arrived 30 months before. Opening the magazine, I wondered what mention it would make of the war with Japan that was to come a few months after it appeared. The lead article was headlined: "Showdown in the Pacific Hastened by Firm Stand of Democracies," and a photograph with the article showed, "Nomura pleading for U.S.-Jap amity." Reading the article as I walked, I nearly tripped over another Jap body, which smelled as bad as all the rest. Beside me a GI made a crack that somehow fitted that photograph of Nomura. "You know," he said. "Nothing smells worse than a Jap - especially when he's dead."

|

SOMEWHERE IN INDIA - Broadway stage shows don't usually rehearse their songs, gags and sketches against the roar of a transport plane's motors, 5,000 feet above the Assam jungles. But a group of airborne soldier-showmen here in India have been practicing their numbers in the clouds ever since they first started their swing around this country to entertain U.S. troops. And thousands of satisfied GI spectators will testify that the unorthodox rehearsal method pays of with results. These airborne GI entertainers are members of the cast of "Hump Happy," a fast-moving, two-act musical comedy that has given soldiers here their first ration of belly laughs since they left the States two years ago. Booked for one and two-night stands at camps all over India, the "Hump Happy" cast travels entirely by air, because there are big distances to cover. Flying most of the day to reach the site of their evening performance leaves the GI troupers with little time for stage rehearsals. So they do their rehearsing en route, running through songs and patter in the cabin of the big DC-3 high over the dense jungles of Assam or the drifting sands of the Sind Desert. So far, they haven't figured out a way to go through their dance routines while in flight. It isn't just that their "stage" is somewhat wobbly; it's because the cabin is jam-packed with a piano, stage curtains, props, footlights and public-address system, leaving little room for the hoofers to practice their steps. The piano and other stage properties have to be hauled along because most of the shows are put on at outposts where these articles are definitely not Army issue. Air-raid alerts have frequently interrupted the shows. But the pay-off came one night when earthquake temblors threatened to destroy the stage. The quakes occurred at midnight, soon after several of the cast had bunked down on cots on the stage. Built of flimsy materials to make it more portable, the stage rocked and shuddered. This scared hell out of the actors, but both they and the stage survived. Taking its title from "The Hump," the range of mountains separating India and China over which several members of the cast had flown as radio operators and crew chiefs, "Hump Happy" is the outgrowth of a makeshift show staged one night

One of the spectators that night was a brigadier general. The next day he had the members of the cast relieved of their Army duties as radio operators, mechanics and office clerks. Then he put a Special Service officer in charge to whip their improvised acts into a finished production for a tour of the other India stations. Maj. Clark Robinson, the officer assigned to supervise the new show, was a natural for the job. He formerly produced stage shows at the Roxy Theater in New York City, served as art director of the Radio City Music Hall and designed the sets and decorations for Billy Rose's Aquacade at the San Francisco Fair. After putting on 37 performances in 29 days in the Assam area, the boys really put the show on the road, or rather "in the air." On their swing around U.S. bases in India, they have covered a territory more than half the size of the U.S. At the completion of their present India tour, they are tentatively booked for extended showings in China and East Africa. The cast had its baptism in "the show must go on" tradition recently when Maj. Robinson was killed in a plane crash. The accident happened at a remote air base where a performance was scheduled the next night. Maj. Robinson had gone on ahead to make advance arrangements. When his men arrived the next day, they were told the tragic news. Although grieved by his death, the cast decided to go on with the show that night rather than disappoint their audience. There are 12 enlisted men in the "Hump Happy" cast, and each of them appears before the footlights at least five times during the two-hour performance. While off stage, they double as prop men and make-up artists. Pvt. George Davis, who emcees the show, claims some of the men are on so often they meet themselves coming off. Besides Davis, who was a radio singer in Brooklyn, the ex-professional members of the troupe are Sgt. Jack Newman of Cleveland, Ohio, a Chicago Opera Company tenor who also appeared in the Broadway productions of "Desert Song" and "Blossom Time"; Pfc. Bob McCollom of San Antonio, Tex., a cowboy singer and guitarist who played minor roles in several

Three of the cast - M/Sgt. John Cobb of Salt Lake City, Utah, a guitarist; Sgt. John Hupfel of Chicago, a singer, and Cpl. Al Pestcoe of Philadelphia, an impersonator - had no previous professional experience. Cpl. Al Roth, onetime Broadway theatrical agent, serves as the show's stage manager and also plays bit parts. The show's three-piece band includes Holden, Pvt. Larry Fishman of New York City, a piano teacher in civilian life, and 1st Lt. Creth Lloyd of Syracuse, N.Y., a guitarist. Lt. Lloyd succeeded Maj. Robinson as officer in charge. Top billing in "Hump Happy" goes to a trio composed of Sgts. Cobb, Hupfel and Sydow, who do an impersonation of the Andrews Sisters that is nothing short of infringement of character. The next best applause-getter is Sydow's strip-tease act. GIs who haven't tested their tonsils on "Take it off!" since they last visited burlesque theaters in Baltimore, Kansas City and Memphis really get in some wolf-calling practice during Sydow's "delayed peel." Sydow uses an AAF emblem instead of a G-string. In fact, the whole show, with its latrine lyrics and gents-room jokes, makes a Minsky burlesque look like a Legion of Decency selection. But it's just what the doctor ordered for the entertainment-starved Yanks in the CBI.

|

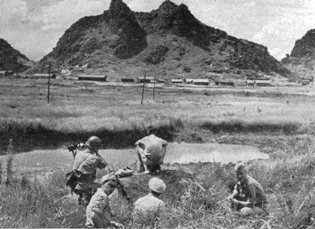

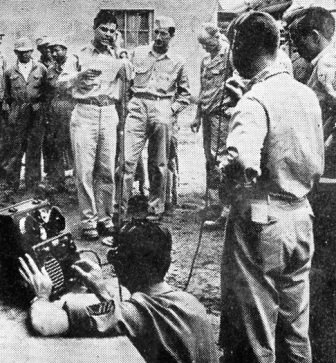

The small group of GIs with the Chinese around Bhamo add up to chow, bullets, medical care and air support - but these are only a few reasons why the Chinese call them "pongyos," or buddies. WITH A REGIMENT OF THE CHINESE 38th DIVISION BESIEGING BHAMO IN NORTHERN BURMA - It was a wonderful spot for an OP - a high mound of earth from which you could look several hundred yards across the trees and fields and scattered houses, right into the center of the city itself. When I walked up to it that afternoon to see whether the front line had changed during the day, a little Chinese Bren gunner who knew me from previous visits, grabbed my arm. "Maygwaw pongyo, maygwaw pongyo!, he jabbered excitedly, pointing to my camera, then to his forehead and then to the path leading to the rear. I knew the words he used meant "American buddy," but I didn't savvy the pointing or the worried expression on his usually happy face, so I shrugged my shoulders and shook my head. Then he made another hand movement, sweeping his fist from high in the sky to his forehead and accompanying his gesture with a long whistle. Now I understood: an American photographer had been hit in the head by a bursting shell. Later that afternoon I found out what had happened. A Jap .70-mm rapid-fire gun had landed a shell on top of the OP just as T/4 Wayne (Bud) Shearer of New Kensington, Pa., a Signal Corps photographer, was climbing up the back of the mound to take some pictures. He was slightly wounded by a hunk of shrapnel which lodged in his forehead. He was lucky, for the same burst ripped open the stomach of a Chinese soldier a few feet from him, and he died on the way to the hospital. Shearer is one of a little bunch of Americans attached to Chinese infantry regiments encircling Bhamo. This bunch is so small you could probably put it in a couple of 5-ton trucks. Nevertheless, without these few officers and GIs with every Chinese division fighting in northern Burma and southwestern China, the Chinese wouldn't get food or ammunition, dive-bomber support or medical care, tactical information, or a record of their operations for the outside world. Most of these Americans have walked as far in the course of the Asiatic campaign - several hundred miles apiece - as probably any infantry outfit in the U.S. Army. Many of them are under fire day after day. Yet none of them are infantrymen and none of them do any shooting, except in self-defense. They are specialists, attached to Chinese divisions to do jobs the Chinese cannot do themselves. They are radio operators, code clerks, surgical technicians, photographers and engineers. When the Chinese soldiers call them pongyos - pals - they really mean it. Even the lowliest ping - Chinese buck private - knows that when the maygwaw make funny noises with boxlike instruments, soon big transports drone overhead and parachutes float down from them, loaded with chow and bullets. When moaning and bleeding Chinese come joggling back from the front on litters, other pongyos fish around in their wounds with

These aren't the only reasons why the ping likes the Americans. Hw also likes the way they return his ever-cheerful grin of greeting and the way they walk hundreds of miles over the mountains and through the jungles with him, then go under fire beside him. But mostly, he admires them for the way they make him feel he's their equal and their pal. There are so few of these GI specialists with this particular regiment that I met every one of them personally in my first 24 hours here. Then I spent a week living with them and watching them at work. Compared to the living conditions in Burma of Merrill's Marauders, their lot is better. Instead of the infantry's K and C-rations, they usually eat the more varied and solid 10-in-1, or B-rations. They seldom have to carry packs, for their personal equipment all goes on mules when they're on the march from place to place. Most of them now sleep in the newly issued jungle hammocks instead of on the ground. They wear cotton khaki uniforms instead of fatigues so they will look at a distance just like the khaki-clothed Chinese to Jap snipers. They stand no perimeter guard duty at night; the Chinese do that for them. Maybe life is not so rosy with other regiments. And it certainly wasn't so rosy in this one until a few months ago. "Look at these," said T/5 Murray D. Weinberg, a radio operator from Brooklyn, N.Y., showing me a chicken and some eggs he had just bought from an Indian in a nearby village. "Back in the Mogaung Valley last spring we would have given our right arm for such chow. We lived for weeks on bully beef, rice, tea and hard biscuits. We slept in puddles of water night after night. Things sure have changed." The Signal Corps radio team of which Weinberg is a member and others like it in the division, have been in the jungles of Burma for 12 months during which they have walked 500 miles, mostly in the mountains. Their job is to keep contact with division headquarters for an American regimental liaison officer. The liaison offers, like Maj. Norman P. Barnett of Irvington, N.J., who is with this regiment, must see that every man in the regiment gets clothes, food, ammunition and other supplies, no matter where in the jungle the outfit might be. They must keep higher headquarters posted as to the progress of the advance, right down to the location of each platoon. Their job takes diplomacy, quick thinking, foresight and - most of all - a lot of legwork in getting the facts to radio back. Occasionally the Japs try to block or intercept messages with their own radios. "When they try to intercept, pretending they are division headquarters," said T/4 Edmond J. Trosclair, a radio operator from Raceland, La., "we just flash the authentication code letters at 'em. If they can't give us the correct reply, then we know they are Japs. One Nip kept asking me to 'Send V's,' which means keep hammering out the letter 'V' until he could tune in more perfectly. That's a GI term but I asked him to authenticate in code. When he couldn't, I just told him to deposit his antenna in a certain portion of his anatomy." Trosclair considers himself lucky in that he's one of the few original radio team members with the oldest Chinese divisions in Burma, the 22nd and 38th, who has kept out of the hospital. Especially, he added, after carrying his 50-pound field radio on his back through some of the more rugged hill country. Eight months ago, Maj. Douglas A. Sunderland of Nashua, N.H., and his portable hospital outfit joined the division at Shadazup in the Mogaung Valley. His was one of several American portable hospitals sent out to relieve Lt. Col. Gordon S. Seagrave, author of the best-seller "Burma Surgeon," and his unit of some of the increasing burden of medical work for the Chinese Army in Burma. Lt. Col. Seagrave's hospital has followed the advance through Burma as closely as ever, and is now the evacuation hospital for casualties in this Bhamo battle. So far, Maj. Sunderland and his pack hospital have walked 500 miles, operating on Chinese wounded under all sorts of conditions. "The only wounded GI we have worked on in all those eight months - and we have treated 2,000 casualties - was this photographer, Shearer, who got a piece of shrapnel in his forehead the other day." said T/4 Joe Metromile, surgical technician from Rochester, N.Y., who has grown a bushy beard since he's been in Burma. "When Shearer came in, we had to look up the ARs to find out how to tag and list him because we had forgotten the American system." The portable hospital has had to improvise all sorts of equipment. T/5 Benny Lucero, plaster man and carpenter from Las Vegas, N. Mex., does most of this. He constructs operating tables out of bamboo, ether masks from adhesive tape cans, ward tents with supply-drop parachutes and blackout operating rooms with walls and ceilings of GI blankets. His pride and joy, however, is a makeshift Hollywood (medical terminology for a little stand on which to rest the leg of a patient with leg wounds and breaks). This he made out of a trench shovel and some scrap wood; it looks like something by Rube Goldberg or Salvador Dali. "We usually set up our hospital in a native hut about 400 to 800 yards from the front," explained T/3 William Quilty of Louisville, Ky., "and sometimes, we think it's a little too close. Like last night when some machine gun bullets went through our grass roof. We've got to be close, though, so litter-bearers can get serious casualties back to us quicker. Also, when we're so close we can tell by our ears when there's going to be a lot of business. For instance, the other night, the Japs staged a big counterattack that went on for about an hour. Bullets and stuff were whizzing all over the place. What a noise! We got ready for a lot of work, and sure enough, we performed 35 operations in the next 17 hours."

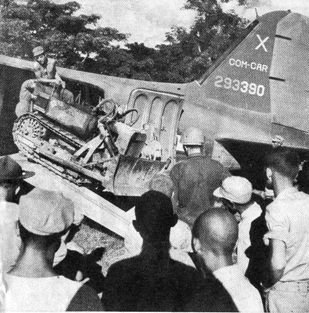

Newest of the American units to join the Chinese offensive is a Tactical Air Communications Squadron, the only one of its kind in the whole AAF. It was attached to the Tenth Air Force, after special training back in the States in ground observation and radio liaison with planes that do close-in bombing. Its crews were sent out with each Chinese, British and American infantry regiment in northern Burma. One of these crews went so close to Jap lines while with the British 38th Division, that it got into a tight spot and when it came out the officer and two of his men won Silver Stars. The officer was Capt. Floy Parsons of Clearwater, Fla., a former Regular Army sergeant. He and his crew are now working with the Chinese regiment. Every night they select targets in the path of the advance with the regimental commander. Next day, Capt. Parsons and a couple of men go up to the front in the sector facing the Jap positions to be bombed. "So damned far up to the front that the Japs have lobbed rifle grenades at us," observed Cpl. Joe Kircher of Brooklyn, N.Y. When P-47 Thunderbolts of the Burma Banshees Fighter Group arrive overhead, Capt. Parsons contacts the planes by air-ground radio, giving them target co-ordinates from an aerial photo. Then the fighters roar in to dive-bomb the Jap positions, as the crew on the ground observes their hits and tells them of their accuracy. The fighters zoom up and circle around after every dive, then scream in again to bomb and strafe. This goes on all day, with flight after flight of P-47s. "The bombing is usually so close to us," said S/Sgt. Francis L. Sparks Jr. of Warrenton, Ga., crew chief and, unofficially, cook for the Parsons gang, "that once a pilot let go his bomb a fraction of a second too soon and it landed 30 yards behind us. A 500-pounder, too. All it did was bury a Chinese soldier who, when we dug him out, was as good as new. But it might have wiped out a whole platoon of Chinese or a perfectly good air support crew, if it had landed a little nearer." A few days later the fighters dropped delayed-action bombs to get at some Japs who were burrowed into deep bunkers. When the bombs went off, the crew saw assorted Jap heads, arms and legs fly into the air 100 yards from them. A Chinese major nearby howled with joy at the sight. "Incidentally," said Sparks, "every GI in our outfit was a Snafu of one kind or another before he got into this work. I washed out of Air Cadet school and so did several of the other boys. A few flunked out of two or three schools in a row - radio, gunnery, radar, navigation or bombardment. So here we are, probably the only guys in the Air Force who walk right along with the infantry and the mules. In a way I'm gonna hate to get back to Georgia, because folks might see my Air Force patch and ask what kind of plane I flew." On the other hand, the Signal Photo cameraman who record the battles with the Chinese, although they have piled up almost as much mileage by foot as the radio teams, are becoming airborne as much as possible nowadays. It helps them to be at the right spot to snap pictures. Some still walk into battle with the infantry, but when a battle becomes so big it needs more photo coverage, others fly into nearby rice paddy airfields in L-5 Piper Cubs. One of these little planes helped T/4 Louis W. Raczkowski, movie photographer from Syracuse, N.Y., to photograph the dive-bombing from a new angle the other day. After grinding out film of the bombings from the ground OPs, Raczkowski went up in an L-5 and focused his camera on the P-47s as they flashed by in their dives to zoom up over black blossoms of bomb bursts. "It was a fine box seat," said Raczkowski, "until I happened to notice a few Japs shooting machine guns at our plane. They were also shooting each P-47 as it came in, but the pilots didn't seem to notice it and I wasn't going to tell them over our radio for fear they would quit that beautiful tree-top bombing before I got all my pictures." Another photographer, Pfc. Donald Pringle of Everett, Wash., has been so close to the Japs in recent days that on two occasions he's had to trade his camera for something better to shoot with. The first time he knocked down a Jap at 30 yards with his pistol. The second time he saw three Japs leap out of their holes during a bombing and start running to the rear, so he tossed a grenade and blasted one of them in his tracks. Five of these Signal Corps cameramen have won combat decorations. Besides the Purple Heart Shearer got for his wound at the OP the other day, two others won the medal for wounds received while with Merrill's Marauders last spring. For landing with the gliders the day Myitkyina airfield was captured, one photographer received the Air Medal and another the Bronze Star. "The only way to get good combat pictures, of course, is to risk your neck," said T/3 Dan Novak of Minneapolis, Minn., who won the Bronze Star for landing with the gliders in the face of Jap fire. "And as the war goes on it gets harder and harder to shoot combat pictures that won't look just the same as what's been shot before. Not to mention the problems of keeping film and camera dry in this Burma climate and then seeing that the film gets delivered by Piper Cub." Airstrips and dropping grounds are an important part of this Burma war, where all supplies are parachuted in and all casualties flown out, usually one at a time in L-5s flying a shuttle system back to Myitkyina, 114 miles away. Because of this a few Aviation Engineers now go along with each infantry regiment to select airstrip sites and direct Chinese soldiers in clearing them. When it developed that Bhamo was not going to fall right away and might take a siege of several weeks, the Engineers enlarged an L-5 strip nearby, to permit Combat Cargo transports to land. The first plane in brought a baby bulldozer needed to smooth out several bad spots on the runway. Ten minutes after the Engineers drove it off the transport, the bulldozer was at work on the strip, so the C-47 could safely take off with a full load of Chinese casualties. The war in Burma, you see, takes a little more than brave fighting. It also takes maygwaw pongyos.

|

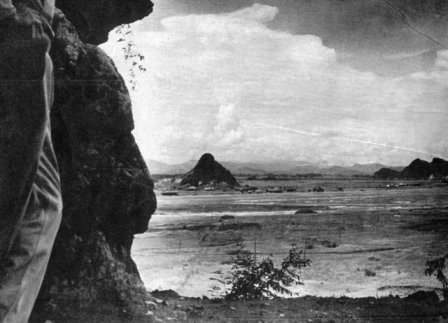

U.S. Forces destroyed this airbase in southeastern China and withdrew along with thousands of civilian refugees before the advancing Jap armies. CHINA - Only 250 miles northwest of the Jap-held port of Canton on the China Sea, in a small green valley formed by jagged outcroppings of granite rock, are the burned, blasted and evacuated remains of Kweilin airbase. Its loss, coupled with the loss of other nearby airbases of the Fourteenth Air Force, is a serious reverse for American arms. It may mean that the war against Japan may be prolonged. Ragged and ill-equipped Chinese armies are still fighting the battle of the eastern provinces against the tanks, heavy guns, cavalry and mobilized infantry of the enemy. Concrete pillboxes, manned by Chinese, have been set up in the streets of Kweilin town, and the machine guns, mortars and ancient rifles of the Chinese are deployed throughout the passes of the mountains of Kwangsi Province in southeast China. But the forward bases of the Fourteenth Air Force have been blown up and deserted by U.S. airmen who got out with their planes while they could. With them went any immediate hope of close land-based fighter and medium bomber support of Allied landings on the China coast. I last saw Kweilin just after the Japanese had taken Hengyang and it had begun to look as if their steam roller would soon reach Kweilin. Non-combat personnel had already been evacuated. At that time the town of Kweilin, a few miles from the airbase, was still quiet and pleasant place. Pillboxes had already been set up in the streets, but Chinese life seemed normal. Rickshas clattered bumpily over the cobblestones. Small bamboo-thatched boats passed up and down the narrow winding river that cuts the town in two. Kweilin has been called the Paris of Free China, and this was not, even at that time, entirely undeserved. The atmosphere of Kweilin was pleasant and leisurely. It was still the most wide-open town in Free China. The women

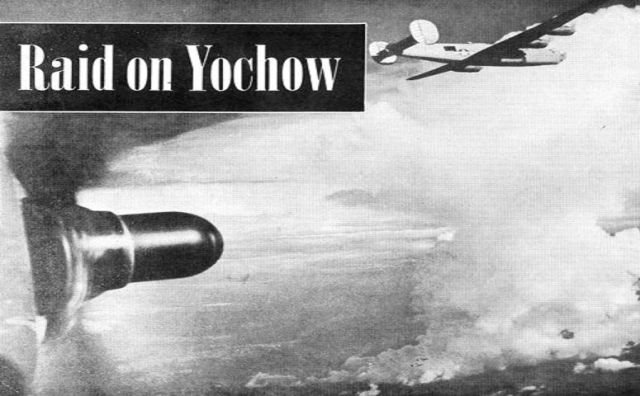

But at the nearby airbase, GIs and officers were tired, jumpy and underweight. The strain of overwork, sleepless nights spent in caves and gun pits, repeated bombing, and food so inadequate it had to be supplemented by vitamin pills, was telling on the Americans. Nevertheless Kweilin was still a fighting airbase. Its 75-mm cannon-packing B-25s and its beat-up P-40s were going out on as many as five missions a day against coastal shipping and Jap motorized columns that had swept down through Changsha and Hengyang toward Kweilin. The first time I saw Kweilin airbase bombed was on a day when Fourteenth Air Force P-40s from Kweilin and other bases had been out in force against the Jap Paluchi airfield near Yochow. By luck or nice timing the P-40 flight caught a number of enemy fighters refueling and destroyed 18 of them. All P-40s returned safely. That night the Japs struck back at Kweilin. At 1930 hours the field was quiet and heavy with moist heat. The sky was cloudless and starry. A bright half-moon hung not far from the sky's center. Some of the men were in the rec hall watching a dull movie about college football called "We've Never Been Licked." A few were already beating their sheets under mosquito nets, trying to sleep through the hot night. Suddenly the Chinese barracks boys began pounding on copper washbasins and from across the field came the thin wail of a siren. It was a One-Ball alert. Men assembled in small groups around jeeps. The Chinese barracks boys ran from room to room, turning off lights and rousing determined sleepers with cries of "Jing bao! Jing bao!" (the Chinese words for air raid). The washbasins were banged again in a different tempo, and again the siren sounded. This was a Two-Ball alert. Jeeps took off with armed men crammed inside and sprawled over the hoods and spare tires. Most of these were men with desk or ground jobs who had volunteered to take over gun positions. Men who had no battle stations dropped into slit trenches or took cover within natural caves in the granite valley walls. The Chinese barracks boys and mess attendants went in single file up the steep side of a mountain, and I

The airbase was blacked-out. Moonlight shone on the runway and the roofs of the buildings. About 2000 hours a red flare came from one of the nearby hills and went over one corner of the field. It was followed quickly by another flare from a hill on the other side and the two flares crossed in an arch directly above the field's main gas storage area. As had happened before, Chinese traitors or infiltrated Japanese were sending up welcoming beacons for the Japanese raiders. From slit trenches, gun pits and caves Americans saw the flares and cursed. The Chinese boys on the mountain top made sorrowful tongue-clicking noises. And now a low pitched moaning came out of the sky and steadily increased in volume. The small guns of the field, none larger than .50-caliber, opened up, arching tracer bullets at the enemy. A few Chinese-manned searchlights flashed on, fingering the sky hesitantly and unskillfully. The valley was bright with light and echoing gunfire. The roar of the Japanese planes sweeping low over the field became louder. A stick of bombs exploded on the runway. The bomber flew on and there was darkness and silence broken only by an occasional rifle or carbine shot. Soldiers in the rocks and on the mountains were out hunting the Japs and traitors who had sent up the flares. About three minutes later the bombers returned, noisy but invisible against the night sky. They came from a different direction this time, passing right over us on the mountain top. The guns and searchlights began to argue it out with them again. There were more explosions, flashes of white light and concussion waves. When the bombers left this time, four small fires were burning near the runway. The third time the Japs came over they hit what the flares had first pointed out - a part of the field's gas supply. Orange flames rose higher than the granite mountains. The bombers came over a fourth time and dropped their eggs on the burning gas. The blaze grew bugger and hotter and brighter until the lower half of the field was lit up as if the sun where shining on it. The bare earthy crags

The planes made a fifth pass, low and right over the fire again, Apparently they were out of bombs and only checking on their night's work, because they dropped nothing more. For a long time nobody moved from his battle station or refuge. The column of fire, huge and hot, shot up in new and terrible billows every now and then. When the fire had sunk to a red glow and the moon had gone down so it was not far above the mountainous horizon, the "all clear" siren sounded and a few lights blinked on about the field. Back in barracks with the lights on, things looked normal. Men walked and jeeped in from their stations. Everyone asked questions about the damage and argued about how many bombers had been over. Most men figured from 4 to 12. S/Sgt. Burl F. Quillan of South Have, Kans., an aircraft mechanic who had volunteered to man a .50-caliber machine gun on the field, sat on the edge of the porch smoking a cigarette, a little shaken by his experience. One bomb had landed about 100 feet from him. He had loaded and fired the gun by himself until it got too hot to handle. He said he thought he had placed a number of rounds in the belly of one low-flying enemy plane. S/Sgt. Bill Gould of Pittsburgh, Pa., came in a little later. He had been in Kweilin town during the jing bao, and had a story to tell of more treachery. Just before the panes came over he had seen several red flares go up over the city and a sizeable house set on fire. Guided by this, Gould said, the bombers had flown straight over the town, turned and headed directly for Kweilin airbase to drop their eggs. "Pretty soon," said one of the men after hearing this story, "the traitors will be sniping at us. After this I'm wearing my gun into town." Next morning the field looked about as it had before. There were a few bomb holes in the runway. A gang of coolies filled then with tamped-down earth before sundown. One B-25 was a wreck. No buildings had been hit, though some roofs had been perforated by fragments and some windows shattered. The earth and rocks in a wide area around the gasoline dump were scorched and littered with burned-out drums. Aside from two lieutenants who were a little beat up from concussion, there were no injured men and nobody had been killed. The burned gasoline would be sorely missed and would have to be replaced by air tankers. But there was still some gas on the field and Kweilin's planes could still carry on the attack. What griped the men of Kweilin most about the deal - more than the bombing, more than the sleepless night, more than the overwork, more than the poor food - was the field's lack of proper defenses. There were no adequate searchlights, no properly equipped night fighters, no large caliber antiaircraft guns. "If we only had a couple of Bofors," the men said. But they knew why supplies and materiel were lacking. The Burma Road was closed and there was no Allied coastal port. All personnel, bombs, ammo, guns and gas for Kweilin came by air from a rear base in China, which in turn had to be supplied by air over the Hump in India. And India had to be supplied from the States. Not long after that, the airbase was abandoned and destroyed by the American forces, and the civilian population of nearby Kweilin town also was evacuated. "Gen. Stilwell and Maj. Gen. Chennault made a final visit to the base," said Sgt. Frank W. Tutwiler of San Francisco, Calif., describing the last days of the airbase. "By this time big bombs had been placed in a pattern planned for

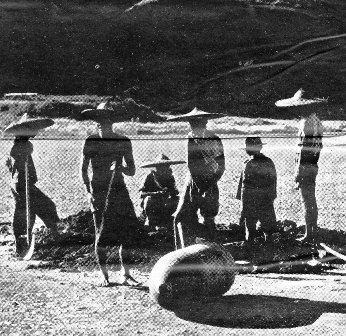

"When the runways were finally blown up and the buildings were fired, we thought the Jap bombers would come over. The flames were certainly a lot better guide to the enemy than those flares the traitors and Jap agents used to shoot off. But for some reason, I don't know why, the Jap planes didn't show." "We knew in advance that the airbase would be blown up and fired, and the boys came around and woke us up about 0100 the night it happened. In an hour two hostels were burning and by 0400 the fighter strip, parachute tower, two more hostels and a lot of miscellaneous buildings had gone up in smoke. A terrific amount of supplies that had been stocked on the field was salvages just before the buildings were fired. The stuff was loaded on planes that came in at the last minute and took off again." "From the day we began preparing to abandon the base, and for a week after the demolition was completed, the people of Kweilin moved out of their town toward Liuchow. Day and night long lines of sad-looking refugees trudged across the field and along the runways, carrying with them pitiful bundles and trinkets, trying to take their world on their backs." "The roads were clogged with refugees, and we could not help thinking what would have happened if it had not been for the Fourteenth Air Force. But our planes kept the Japs from coming over and strafing the refugees, as the Nazis had done in so many countries of Europe." "At the railroad stations it was the same story. The Chinese crammed the cars to the very tops, they swarmed over the locomotives and hung to the couplings between the cars and even the rods under the cars. And everywhere you saw the great unwieldy bundles of the people, everything they had to their names." "There was a shortage of coal, and some of the trains had to stand in the station for as long as eight hours after loading up. The smell became oppressive and the flies crawled all over in black clusters but somehow people went on housekeeping and living." "An evacuation service that had been set up to handle the refugees was slow in getting started and it was soon engulfed by the flood of people. At first advance payment had been required for passage on the railroad but by the time the last 20,000 people left Kweilin, all the railroad wanted to know was where you were going - and there wasn't much choice." "Back in the half-burned city, the streets were silent and deserted, except for occasional soldiers, and some people who were looting and breaking open store fronts here and there." Two of the last GIs to leave Kweilin were S/Sgt. Willard M. Golby of South Orange, N.J., and Cpl. Frank J. Kelleher of Scranton, Pa. "We got on the train at Ehr Tong station to leave Kweilin and had to sit there and wait for six days," said Golby. "It was the last train from Kweilin. We were transporting equipment and had to keep civilians out of our boxcars by posting guards." "The sixth night we heard explosions and the sky was lit up with the fire from the hostels and airfield being destroyed. We were supposed to got to Liuchow by train but the transportation officer told us that there was a derailment up the line and the train might not be able to leave. We loaded up two trucks with the equipment we were guarding and headed over back roads. On our way we passed an army of refugees all going in the same direction - away from Kweilin." "But we were cheered by the sight of a different kind of army - Chinese soldiers - moving in the opposite direction. They were going to make a fight for Kweilin."

|

The "Forefathers of Asia" came with promises of freedom and wealth, but brought nothing to the people of the little city but torture, plunder, intrigue and violent death. WITH THE CHINESE 38th DIVISION BESIEGING BHAMO IN NORTHERN BURMA - On the sultry morning of May 3, 1942, the first troops of the Japanese Imperial Army entered the little city of Bhamo, hot on the trail of thousands of refugees fleeing north with the faint hope of reaching the safety of India. These men of Nippon came to Bhamo with the glowing promise of freedom and wealth under what they called the Asiatic Co-Prosperity Sphere. Today, two and one-half years later, the Chinese 38th Division has fought its way to the outskirts of the city in a drive that will eventually re-open the Burma Road. While with a regiment of the 38th, I have talked with dozens of people of Bhamo about their life in the Asiatic Co-Prosperity Sphere. They have described it all in detail, and it has been a life filled with plunder and indignities, brutality and intrigue. Those first Japanese, the people said, had swept through the undefended city in trucks, garbed in clean khaki uniforms and brandishing shiny new weapons without even bothering to leave a garrison force there. They were after bigger stakes; the capture of the whole of northern Burma, which would completely block off the only land route from India to China and give them a springboard for a possible later attack on India itself. They were happy and laughing as their long convoy of trucks rumbled over Bhamo's new tar highway. When the people of Bhamo watched the Japanese roll by, they did so with silence and concern. Their city, second largest in all of northern Burma with a population of 8,000, had been an important point on the route to China ever since the

Dome of the people of the little city realized, that sultry May morning as the Japanese trucks thundered by, that their city's role as a crossroads of the Orient had come to an end. And they wondered what would be their fate. ABOUT A MONTH later, after news had trickled back through the jungle grapevine of butchery and plunder and rape in Myitkyina and other places to the north, a second group of Japanese troops arrived in Bhamo. These weren't infantry troops. These were troops with tons of equipment and supplies who planned to stay awhile - service troops. And with this second batch of Japanese were a number of hard-faced men who were known as the J.M.P. The initials stood for Japanese Military Police, but they were not mere MPs. The Nazi word for them is Gestapo. The people were soon to find this out. "The Japanese settled themselves in the best buildings in the city - the government houses, the theater, the jail, the commercial blocks, the best homes - and the churches." one citizen told me. "They made a great point of entering the churches, breaking up crucifixes, burning holy books, looting anything of value and then turning them into barracks. They took the priests and nuns and other holy people and threw them into a compound." "Then the J.M.P. registered every inhabitant of the city and its outlying villages - the Burmans, the Indians, the Chinese, the Karens, the Kachins and the Anglos. Any who could speak English were at once viewed with suspicion and any who had worked for the Burma government were looked upon as British agents. The J.M.P. asked each person all sorts of questions slanted to bring out anti-Japanese beliefs. Later, answers to these questions resulted in several tortures and deaths. "They asked each of us to state his occupation," said one man," said one man, "and if they ever caught us engaging in another occupation after that, they considered us spies." After the registration, gate passes were issued to every person. Sentries were posted at places all over town, and an order was issued that passes must be shown to the sentries whenever requested. Thereafter, every sentry forced passers-by to automatically bow low and show their passes as a mark of humility and respect. "If we ever forgot to bow to a Japanese," a woman said, "he would slap us in the face. Sometimes, he would even lash us, or prick us with a bayonet." Next the Japanese came around to each house and took what they wanted from its inhabitants. They took fowl, eggs, rice, clothing, curtains and furniture. And they paid nothing. When the people protested, the Japs merely flashed toothy grins and assured them they would be paid later, when the new official Burma currency arrived. "The new official Burma currency turned out to be Japanese invasion money," a merchant explained. "If we refused to take it in exchange for what they got from us, saying we wanted to be paid in British Burma currency which we knew was backed by silver, they told us either to take their invasion money, or they wouldn't pay us at all. Soon we began calling it 'red paper.' Among us, ten rupees of this red paper were worth only on British Burma rupee. It was a common sight at the Bazaar, which Japs took over, to see our people buying back from them a sack of rice we had grown with great handfuls of this red paper. A wheel-barrow full of it would buy, maybe, a yard of cloth." Between themselves, many of the people continued to trade with the British Burma currency, despite the fact that the Japs threatened dire punishment to any man caught with it. Periodically, the Japs staged raids on houses of persons suspected of possessing any. Often a Jap would search a man's clothes on the street to see if he was carrying some. Sentries sometimes used their power to search for money as an excuse for forcing women who passed by to strip completely and stand nude on the street as the sentries made a pretense of carefully inspecting each article of their clothing. THE JAPANESE occupation of Bhamo soon reduced the city from a once flourishing center of trade to virtually a ghost town. River traffic up the Irrawaddy from Rangoon and Mandalay was, for the most part, taken over by the Japs to supply troops fighting in northern Burma. And of course the Burma Road had ceased to function as a commercial trade route. Stores shut down as stocks of cloth, household goods and other necessities ran out. The people had to get along on what they had before Bhamo fell. Their clothes became threadbare and their living more primitive. "The Japanese brought their own women with them," said an old man. "The women were called 'comfort girls' and they were mostly Japanese or Korean. They were billeted in a big house of ill fame. Occasionally toward dusk, we would see them out for a breath of air, wearing fine clothes taken from European houses in Singapore, we heard. Evidently, the Japs took turns at the place on a regular rotation system, for we noticed different faces entering and leaving the house all the time. But the Japs didn't confine themselves to these comfort girls. They used to walk from house to house at night among the surrounding villages, forever smelling of saki and pick out Burmese girls, promising them an their families special favors if the girls would live with them. There was little the families could do about it, unless they wanted to risk sending their young women out to live in the jungles.

Although the Japs, when in an expansive mood, presented themselves to the people as the "forefathers" of all Asiatic races, they did nothing to weld together their newly acquired "descendents" - the varied people of Bhamo. In fact, they did the direct opposite. They tried to play race against race, religion against religion. They tried to turn Burman against Indian, Indian against Chinese, Chinese against Kachin and Kachin against Burman. "They would come to me," recalled a Burman, "and mention someone I knew. They'd say: 'He is no good, is he?' We hate his race. We like your best of all. We want to help you, but we cannot until we get rid of him and his people. Do you know if he has British money? Do you think he is a spy?'" Except for the Kachins, who fled to the hills and carried on guerilla warfare throughout the Japanese occupation, the Anglos were hated by the Japs most of all. The Anglos are people whose fathers were European and mothers Burman or Indian. The J.M.P. rounded up the Anglos and put them in the same compound with the holy men and the nuns. Then they told the Anglos they would have to pay for their own food, clothing and necessities. One villager was selected by the J.M.P. to bring in such items to sell to the prisoners at regular intervals. "The J.M.P. selected me as sole supply agent," one man explained to me, " because they did not want many people entering and leaving the compound for fear they might carry out information from the Anglos to the Allies. They let me know that if I ever did anything to arouse their suspicions, they would torture or kill my people." About a month before the Chinese 38th Division arrived in the vicinity of Bhamo, The Japs sent all the Anglos south by an Irrawaddy River boat, bound for Mandalay. All that each was allowed to bring with him, according to the supply agent, was his bedding and one box of personal belongings. What was left was confiscated by the Japs. "The Japanese prevented us as much as possible from getting any news at all of the war or the outside world," a fisherman said. "When your American planes flew over every once in a while to drop newspapers and pamphlets that we knew told the truth (Published by the OWI and the Psychological Warfare Division) the Japs threatened to shoot anybody caught picking up, reading or possessing one of them. Of course, we read them anyway." "The Japs never bothered to distribute newspapers of their own. Instead they would tell us, when they came around to our houses to collect food, of their great land, air and naval victories. They said they had bombed America and India, and they had landed in Australia. They made all Burmese children attend a school they set up in town, in which the Japanese language was the main subject. About the only other thing that was taught, the children said, was Japanese political propaganda." One of the villagers had been a government jailor in another city in Burma before the war. He had come to Bhamo to escape the bombings and warfare there. When the Japs came into Burma, they had liberated all convicts and set them against anybody who had been in the employ of the Burma government in peacetime. Some of the prisoners trailed this ex-jailor, finally catching up with him at Bhamo. After the Japs had repeatedly questioned him and announced their suspicions toward him, the convicts got their opportunity. One night they entered his home with long knives, grabbing him and hacking away until he was covered with blood. Then they left him to die. He didn't die, but he is so badly crippled today that when I offered him a cigarette one of his children had to put it into his mouth and take it out again. He has to be spoon-fed by members of his family. His right arm is cut off at the forearm, his left arm is broken so he cannot raise it to his mouth, two of the fingers on his left hand are missing and the others are stumps, and there are deep wounds in his head and body. When the Japs heard about the assault, they came around in little groups to stare at him, their faces betraying their satisfaction. They let it be known they were not responsible for wrongs committed by civilians against other civilians - unless the wronged civilians happened to be actively aiding their forces. Most of the atrocities committed during the occupation of Bhamo, however, were committed by the hard-faced men of the J.M.P. The leader of this Nipponese version of the Gestapo in Bhamo was a Lt. Ishikawa, a tall, stocky, cunning sort of bully who was well-versed in the arts of intrigue and torture. "Ishikawa and his gang indulged in periods of torture and murder from time to time for two reasons," declared a young farmer. "First to boost their morale each time word seeped through of a new Allied victory. Second, to keep us aware of the consequences of disobeying Japanese orders, or being suspected of sympathy toward the Allies." The crimes for which the J.M.P. meted out the harshest punishments were: Refusal to give them information about other citizens; refusal to bow to sentries, or turn over foods and other goods when requested; possession of pre-war Burma currency and the making of any statement or move unfriendly to Nippon. "Some offenders were tied to posts and bayoneted in the ribs dozens of times, so they would slowly bleed to death," said a former doctor. "Then their bodies were left under guard for awhile as an object lesson for the people to see. The J.M.P. dealt with others by alternately pouring boiling water and then cold water into their mouths. Or tying them to the ground and rolling full petrol drums over their prostrate bodies. They hung some 'offenders' from the waist, or the thumbs for hours at a time. Or they tied them up by their toes and let them hang head down until their faces were purple and they had fainted. They tied others in gunny sacks and threw them into the river. Once they captured a man who was trying to make his way north to India. First they forced him to dig his own grave. Then they slashed his body to a bloody pulp beside it." Lt. Ishikawa isn't in Bhamo anymore. He disappeared one day and the Japs told the people he had gone south to take a bigger assignment. When the Chinese and Americans captured Myitkyina, 114 miles north of Bhamo, last summer, word of the event got back to the citizens of Bhamo through some hill people who passed through town. Of course, the Japs didn't tell the people about Myitkyina until long afterward when they realized the people already knew. Instead, a propaganda officer went around to all the villages announcing that the Japanese had invaded India (which they had with a penetration into the Kohima=Imphal area of Assam that later resulted in the annihilation of three Jap divisions by the British 14th Army). He ordered the people to give victory dinners and attend a mass meeting on a certain night. When the night arrived, the Japs turned up at each of the dinners with bottles of rice wine. Then they proceeded to get roaring drunk and stood up to jabber flowery speeches until long into the evening, extolling the might of the Japanese Imperial Army. But the tide was turning for the Japs in Bhamo. Shortly after the celebration, a sunken-cheeked and fever-ridden stream of Jap soldiers began to stagger into town down the road from Myitkyina. Some were wounded, others had sores all over their bodies and none of them were warmed. They brought their women with them - diseased creatures in ragged men's clothes. They also brought what they could of loot pillaged from the people's homes there - thousands of pre-war silver rupees, gaudy ornaments, opium and luxuries. "We will never forget those bands of bedraggled and broken men," said an 80-year-old grandmother, as the corners of her wrinkled mouth curled in a sardonic grin. "We couldn't believer they were the same cocky conquerors who rolled through here two and a half years ago, boasting that they were the ones who had captured Singapore." "The Japs in Bhamo refused to take them in, even refused to give them food or medicine," she continued. "In fact, they accused those who weren't wounded as traitors and shot many of them. They called the others deserters. So these horrible-looking men came around to our houses, begging food if they had nothing to offer us for it, or offering in exchange for their silver rupees, opium and other stolen property. Many of us gave them food just to get rid of them. Then they went away to the south." After that the Japs in Bhamo quit boasting of their victories. Their faces became grave. Their tempers grew short. They warned the people that the Chinese and Americans and British were coming to Bhamo, coming to steal and kill and demolish everything. The people nodded, but they were marking time. "Three months ago American planes began bombing the city regularly," said a former riverboat owner. "The bombings were remarkably accurate, for they hit one or two supply warehouses and also Japanese headquarters. The Japs were

For more than two years the Japs in Bhamo had been arrogant and happy. They used to have big parties with plenty of women and rice wine, parties that lasted all night. But now they sent their women south. They used to fish in the Bhamo lakes for hours at a time, for they loved fish. But no more - the lakes were too close to places the American planes were bombing, They used to come around to the people and ask them for sugar so they could make candy and cakes, for they were extraordinarily sweet-toothed men, but now they seemed satisfied with a simple meal of rice and fowl, which they ate in furtive haste. The Kachins in the nearby Sinlumkaba hills - always the mortal enemies of the Japanese - pulled a grim trick that only added to the Japs' uneasiness. "One night some rafts floated down the Irrawaddy River with Japanese soldiers, rifles in hand, standing beside the masts on each of them," grinned the fisherman. "Instead of coming ashore at Bhamo, the rafts swirled right by on the swift current. The Japs in Bhamo sent out boats after them. When the boats came back, the Japs in them were not jabbering as usual, but silent and shaky. Then we found out what had happened: The Kachins had killed some Japs patrolling the northern approaches to Bhamo and had lashed their bodies upright to the rafts, allowing the rafts to float down the river to fool and terrify the Japs here. The same kind of rafts bearing dead Japs floated by on later nights, but no boats went out to them after that. I guess the Japs had had enough." But the highlight of the vengeance of the people of Bhamo during the Jap occupation was the incident of the airdrome. Months ago the Japs decided to build an airdrome in Bhamo. They picked a site then ordered each village to supply a certain quota of coolies to work on it every day. If a village did not send its quota, the Japs exacted food and money as punishment. All the people in the village nearest the airdrome site were forced out of their homes, which the Japs burnt down. For week after week the people of Bhamo, old and young, frail and strong, labored by hand under the muzzles of Jap rifles to build the airdrome. Finally it was completed. The Japs held a big celebration for the event, climaxed with the landing of the first planes. As 25 silvery Zero fighters roared overhead in tight formation, the Japs began to cheer. Then the planes peeled off and began to land as the Japs cheered louder. But something was wrong. Four of the fighters reeled into the ground and crashed in flames. Suddenly the Japs grew silent at the sight, then they turned to the people and were red-faced with anger. "You have sabotaged our airdrome!" they cried. "You will pay dearly for this!" "No, replied the villagers of Bhamo, "we did not do it. It is a fine airdrome, but it will forever be ill-fated. You chose to build it on the hallowed ground of an ancient cemetery, over the graves of our forefathers. The spirits have haunted it and they will haunt it always." The Japs said this was nonsense. But soon afterwards American bombers made a series of raids, dropping their bombs all over the airdrome and wrecking eight planes. So many Japs were killed that they were not buried separately but thrown into a bomb crater and covered with earth by a huge stone roller. "After that the Japs must have believed us," said the merchant, "for the remaining planes climbed into the sky one day and flew south, never to appear again. And whoever mentioned the airdrome thereafter in the presence of the Japanese was liable to severe punishment." When the Chinese fought their way to the airdrome recently, it was overgrown with high elephant grass. And the Japs, fearing Allied glider landings would climax its evil history, had erected huge wooden barriers and dug deep holes across its entire length. "To us," concluded a citizen of Bhamo, "what happened at the airdrome, although it actually was nothing but a chain of coincidences, will always remain the greatest victory of the citizens of Bhamo over the Japanese."

|

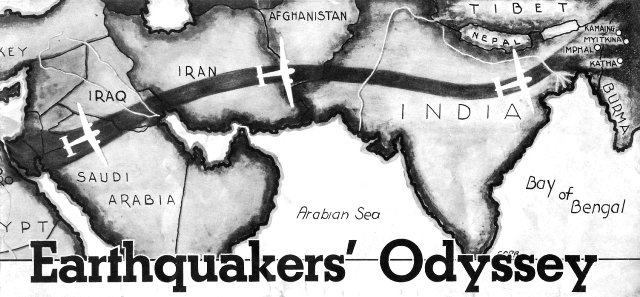

lights in their whirlwind tour of 24 airfields on five battlefronts. A MEDIUM BOMBER BASE NEAR THE ARAKAN FRONT, INDIA - Although the ground men of the Earthquakers Bomb Group have been at this field only four months, they feel like they've been here a long time. That's because they have been here twice as long as at any other field in 28 months overseas - a record that makes them probably the movingest outfit in the whole AAF. In their first 24 months after leaving the States they were based at 24 different airfields, stretching from the Western Desert of Africa to the mountains of Italy to the rice paddies of India.

Unlike most bomber outfits, in which the combat crews do all the sightseeing while the ground men stay behind and take the monotony, the Earthquakers have seen four full sets of combat crews get in their missions and go home, while the ground men have moved more than half-way around the world. Maybe that explains why new combat replacements, fresh from the States, listen with awe when a few old ground men of the Earthquakers get together to spin tales of their wartime travels, which the old-timers do at the slightest provocation, such as when the monthly PX beer ration comes in. "Just before we left the States in July, 1942," begins T/Sgt. Charles A. "Bull" Metcalf of Bartlesville, Okla., a flight chief in the Black Angel squadron, "we got our first hunch of where we was goin'." Our outfit got a complete shipment of brand-new B-25s painted as pink as a baby's blanket. That sure wasn't camouflage for the jungles or Europe, we figured, but it would fit in pretty well with the desert. Sure enough, two months later we were on a stretch of sand known as Ismailia in Egypt, unpackin' and gettin' ready for action." The Earthquakers moved as the Allies advanced in North Africa and into Italy, sometimes spending only a few days or a week at one base before moving again. Soon they were thinking of their next possible destination, home.

The ground men had been 19 months in an 18 month replacement theater, so they were in high spirits. They made up a pool as to their destination in which 60 percent said England, 25 percent the United States and 5 percent (probably the Intelligence Section) the CBI. "From then on," recalls Metcalf, "we didn't mind nothin! We had to crate our equipment with Itie nails that bent in two after a couple of hammer-blows and with wood that split if you looked at it. But we didn't mind that. When our motor convoy reached the port of Taranto and we froze our ears off in drafty tents and ate cold C-Rations in the dead of winter, we didn't mind that, either. We figured we was headin' for a better place - England or America." "Yeah," grins Wisdom, "we were all very happy. That is, we were until the ship turned left off Sicily and headed east. Then our hearts fell. A month after we left Italy we got to India. We've already been in half a dozen places in this theater, but at least we've been at this base long enough to do our laundry and allow our mail to catch up with us." When the Earthquakers arrive at a field near the India-Burma border last March, the British were busy repulsing a Jap drive into the Kohima-Imphal area of Assam that nearly severed the Bengal and Assam Railway - the vital supply link to trans-Hump airfields and to Stilwell's Chinese-American offensive in Northern Burma. The British 14th Army troops needed ammunition desperately to counter this bold Jap penetration of India. So one of the first missions of the Earthquakers was not to bomb, but to haul more than 6,000 pounds of ammunition to Imphal. "Soon our B-25s went into action to support both the Chinese drive in Northern Burma and the British counter-attack in Assam," says Oxford. "They bombed the Jap bases like Myitkyina and Kumaing and Katha. They ripped up railway bridges and junctions. They caught Jap planes on the ground in raids on airfields. And then in June the four month monsoon season set in to give us a new batch of trouble." "Trouble is right," agrees Metcalf. "The weather was so thick the birds could walk on it. Our planes were lucky to get a day clear enough to see the target. And even if they did, they still had to cross and recross the 9,000-foot high Chin Hills, which were always blanketed in a few thousand feet more of clouds. We ground men soon made some delightful little discoveries about the effect of constant rain and dampness on a plane. Metal parts, for instance, rust or corrode. Fabric rots and leather gets mildewed. Radio equipment goes on the blink and machine guns jam up. Sometimes I long for those desert days, when all we had to worry about was dust storms."

For several months the air over Burma has been remarkably free of Jap fighter opposition. It is not uncommon for a combat crew man to complete 75 missions without getting a look at a Zero. And except for a few hot spots, ack-ack is light compared to that in Europe and the Pacific. The weather is certainly the biggest enemy. Occasionally, though, the Japs push some fighters into a place just to surprise Allied bombers. "Just last month one of our squadrons ran into a nest of Jap fighters and had to stand 'em off for one hour and ten minutes," Wisdom states. "Tenth Air Force told us that's the longest sustained air battle in this theater. We lost one ship but shot down three Japs and three probables." "Yeah, when it comes right down to it," concludes Metcalf, "these combat crew guys - glamour boys, if you like - wherever we've been have done a terrific job. Damned if I'd go out and risk my neck several times a week just so's I could go home after 75 missions. By the way, talkin' of going home, I've been movin' around so much overseas this last 28 months that I haven't kept up much with the news. Just what is this here replacement policy I been hearin' about lately?"

Adapted from the original story

|

|

A former master sergeant in the Tenth Air Force in Burma, who was shipped overseas twice and twice found his destination to be the India theater, now finds himself a second lieutenant for the second time in three years of soldiering with two armies. This active warrior is John C. Wyllie of Charlottesville, Va., recently commissioned in the field for outstanding work with a combat unit of the Tenth AF EAC. His accomplishments were made in the Myitkyina-Mogaung campaign where Wyllie was chief of a six-man communications team. There the "zebra-sleeved" chief put the finger on countless Japs while bombers dropped their loads. The fingering was so close that a number of bombs fell within 50 yards of the crew. The annihilation was thorough, the leadership rewarded by Wyllie's second commission and a permanent assignment that is a wide distance apart from the lieutenant's civilian business. The 33-year-old looie was a professor at the University of Virginia. He characterizes the studious gent who likes to put prehistoric bones together but Wyllie is doing the opposite by a good job of dismantling the Japanese. He entered the university at the age of 16 and concluded his formal schooling by becoming the director or rare books and manuscripts. He's been in 26 countries and republics and is a seven-tongued linguist currently engaged in learning Hindustani. He's clubby too, with membership cards for these: The American Institute of Graphic Arts, Modern Language Association of America, Bibliographical Society of Edinburgh, Societe des Ami de la Bibliotique Nationale, American Library Association, Virginia Library Association, Society of American Archivists, American Historical Association, The New York Grolier Club and the Farmington, Va., Country Club. His first commission was given him by the British Army which he joined in 1941. "Uncle John," as he's called, volunteered as an ambulance driver with the Royal Army Service Corps. He sailed for India and trained in Bombay. Then he shipped to North Africa. He worked in Tobruk until it was captured by Rommel's army. He was commissioned by the British during the heat of battle for the fortifications that later helped to spell doom for the Desert Fox. After more duty at El Alamein, Wyllie's enlistment period was up. He then sailed for America to join the U.S. Army. He was sworn in at Camp Lee, Va., leaving for his second overseas assignment in February 1944. Wyllie breezed through six enlisted grades to his master sergeancy five months after joining his unit.

|

|

Mail-Order Marriage NORTHERN BURMA - When T-4 Robert Sternad of Cleveland, Ohio, returned from a month deep in the jungles, he was feeling pretty weak. Eating sparse front-line rations in his job as radio operator with an outfit that had been fighting the Japs, he had lost pounds, and a bad fall had knocked out three teeth. Waiting for him at the base was an ominous-looking official envelope, which Sternad was sure was bad news. But when he opened the envelope, Sternad was all smiles. "Hey fellas!" he yelled. "Looka me - I'm married!" Inside was a contract he had signed weeks before, marrying him to Dorothy M. Arelt of Cleveland, and now countersigned by his bride, a minister and lawyer. Although the honeymoon will have to wait, that night there was a GI wedding supper and party at which the rationed beer flowed like unrationed beer. After the party the groom went to bed alone - but happy. GI Foster Fathers SOUTHWEST CHINA - Whenever a GI truck passes a certain small village on the Burma Road, it honks it's horn twice. Then the little blind girls of T'ien Kuang know they're not forgotten. T'ien Kuang is a mission school of the Lutheran Church. The 37 Chinese children there are casualties, bombed out of their homes and blinded by shrapnel or wartime diseases. Troops of the Service Forces in this area - warehousemen, welders, electricians, mechanics and convoy drivers - have paused in their work of supplying Chinese and American soldiers and raised shekels to support this little school. Recording the Dialogue of War A FORWARD B-29 BASE IN CHINA - Ten minutes before one of the B-29s in the first surprise Superfortress raid on Japan arrived over the target, the industrial city of Yawata, a crew member switched on a small machine about the size of a portable typewriter, which was hooked up with the ship's interphone system. A three-inch spool of thin wire inside the machine began to unroll. All conversation over the interphone during the target approach and the bomb run were recorded on the wire. A week later, back in the States, home folks listening to their radios were able to hear the voices of the B-29 pilot, bombardier and other crewmen as they went about their deadly business over the big Japanese industrial center. Most of the profanity and all references to secret B-29 devices were edited out of the sound track. But this little spool of wire, played back over the nation's broadcasting systems, must have given the home front the real feel of