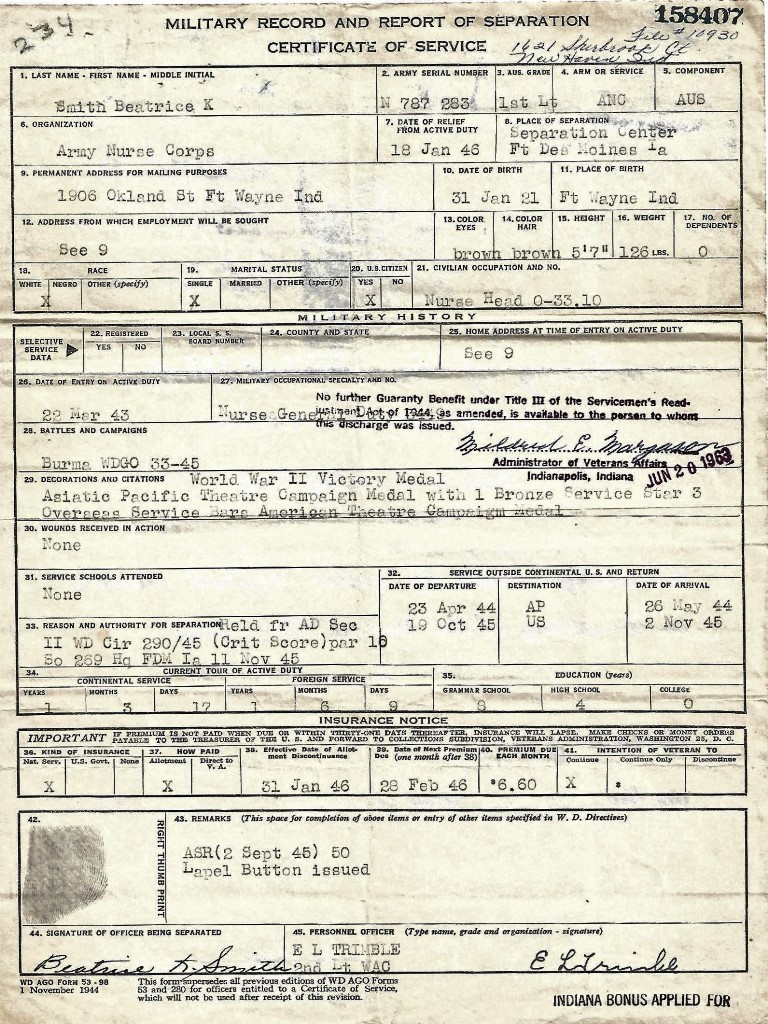

The news came at last - our orders to go overseas. Annie and I had been at Freeman Field, Indiana for about eight months, waiting for our orders for weeks. Annie was my best friend, or as we say in the Army, my best buddy.

When the chief nurse came with the news, we were overjoyed. Capt. Crumm came out of his office and said "What's the excitement?" In chorus we said, "We're going overseas!" "And you're happy about that?" he said.

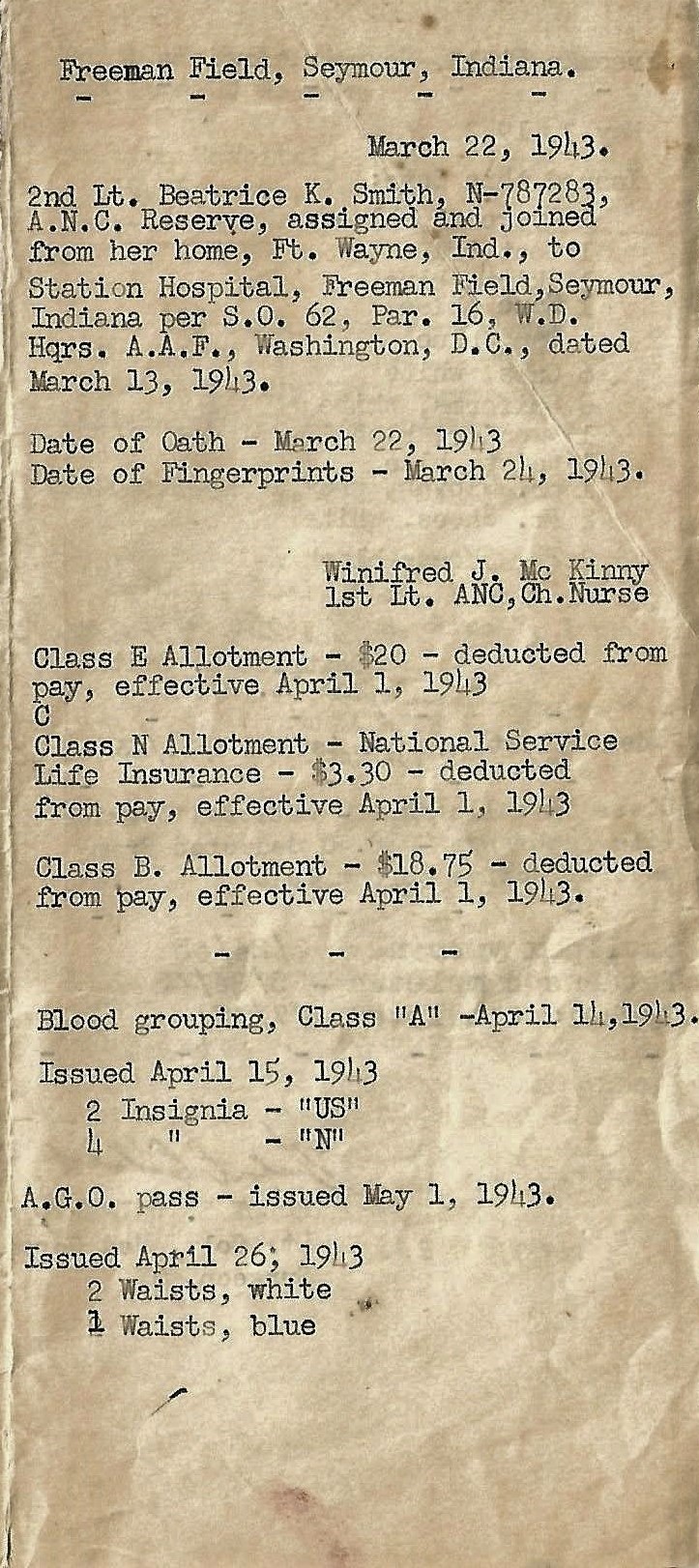

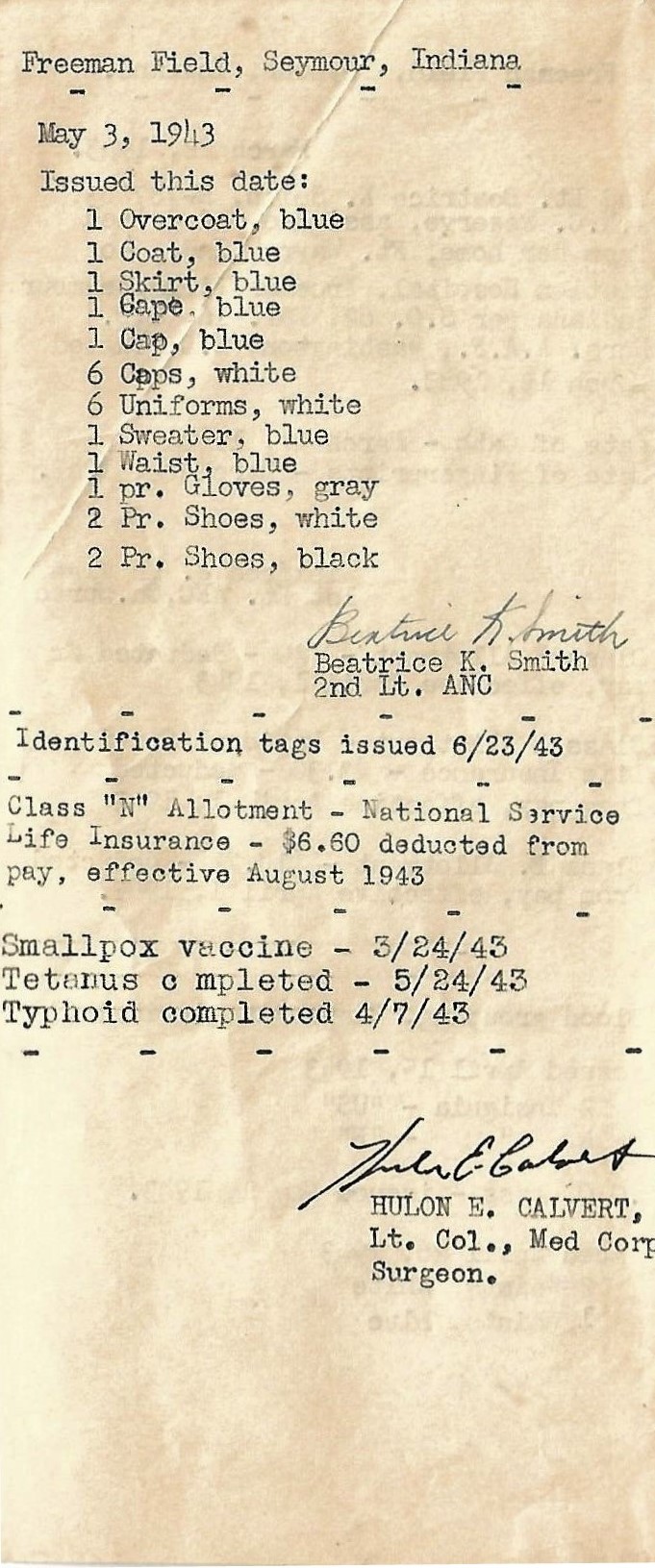

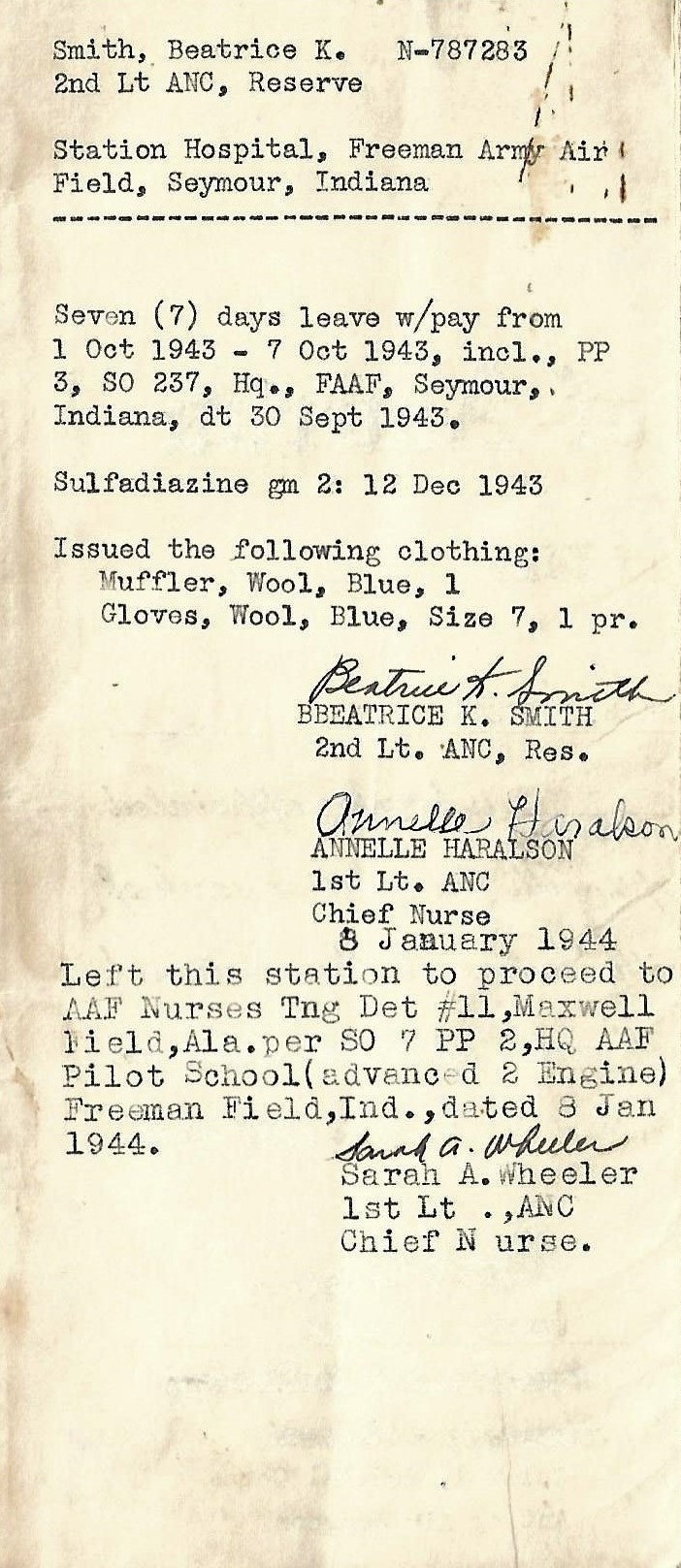

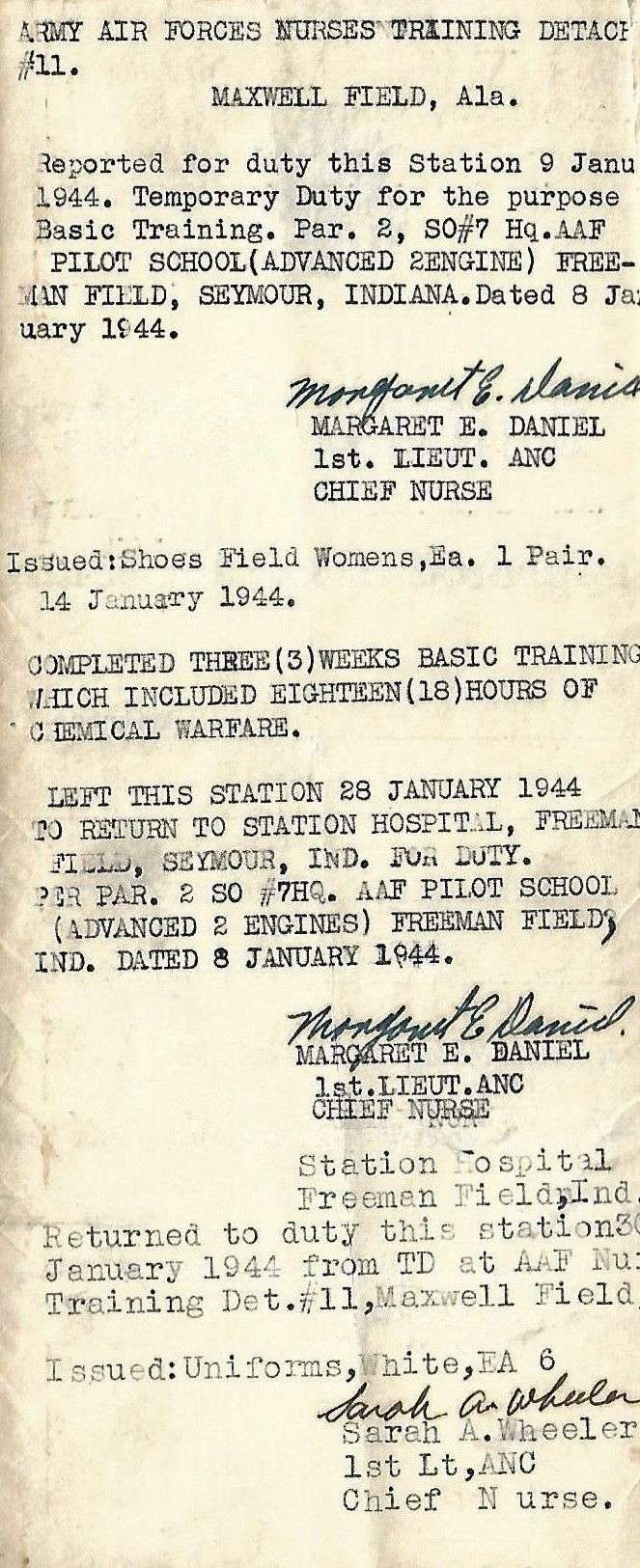

We sat up half the night talking about where we would be going. "Maybe France, or England, or Asia!" Then we said goodbye to our many friends and were off for Maxwell Field, Alabama for basic training. It was a beautiful field, and I was especially moved to see the cadets drilling, with the nurses in white uniforms marching past them - their capes flying over one shoulder. I loved the Army.

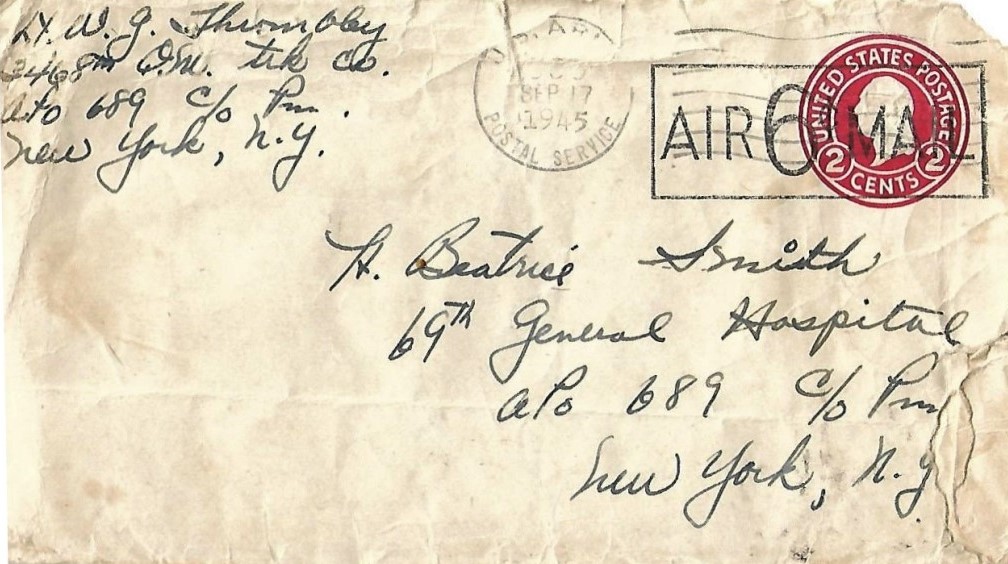

We got through basic training and were sent back to Freeman Field when our orders came to go to Camp Swift, Texas. Our unit, the 69th General Hospital, was being set up. Texas was beautiful, and it was great to have a friend sharing all these adventures.

From Camp Swift, we went to Camp Patrick Henry in Newport News, Virginia. We were there a few weeks when we were awakened around 3:00 in the morning. The ship was in. As with most ships in wartime, we left the port quietly. We were in full battle gear wearing our fatigues and helmets. Our blankets were rolled on our packs. Our foot lockers would go on board too. When we walked up the gangplank, the boys cheered.

When the ship pulled out, I got goosebumps. We were leaving our blessed land to help the boys who might need us. Annie was by my side as we watched the shore disappear. Again, we wondered where we were going. We were out a long time when we spotted land. Where was it? The answer came - we were in Mombasa, Africa - lion country. There, we took on supplies. I kept saying over and over to myself, "This is Africa. You're in Africa!" With travel as it is today, that doesn't seem like much to be thrilled about, but this was 40 years ago and few Americans had been to Africa.

We set sail and arrived in Capetown. We were given leave and went ashore. We had quite a night on the town! After several days, we were off again. All it all, it had been 49 days on board when we landed in Bombay, India. We left the ship and were loaded into Army trucks. It was dark, and India really seemed different. We sang all the old Army songs as we traveled through the hot night.

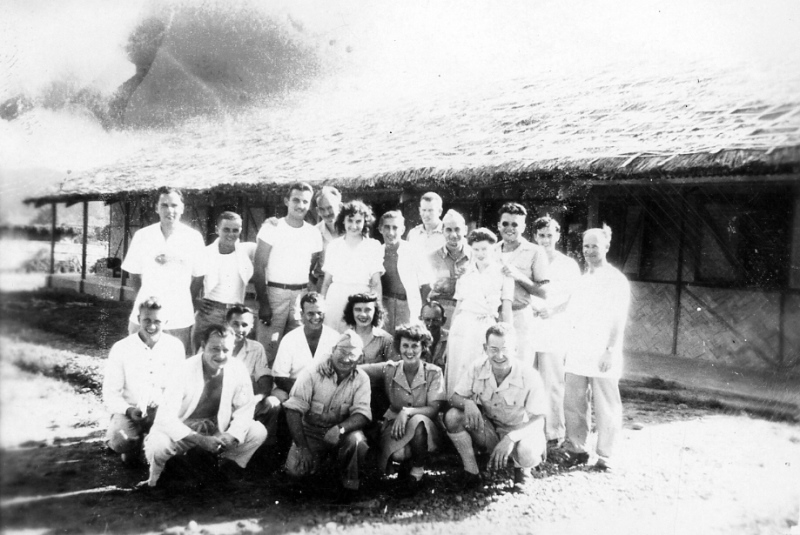

The next day, we explored Bombay. The shops were fascinating, but the conditions the people were living under was frightening. So many malnourished people and children with distended stomachs. Many running up to us begging. Being brought up in America, I had never seen anything like this. It shook my faith - I wondered where God was.

The next day, we went by truck to the train. It was nothing but boxcars with windows cut out and long seats to sit on. In the corner was a latrine. It did have a door. We climbed aboard, not knowing where we were headed. The heat was intense - about 120 degrees. Annie and I were thrilled that we were really roughing it! We had a thirst for adventure and were getting our share.

We were issued K-rations. For those of you who do not know what K-rations are, they are small boxes marked for breakfast, lunch or dinner. Inside were small cans of food and a small, hard candy bar. We filled our canteens with water, since there was no water on the train. It pulled slowly out of the station.

We were not on board very long when it began to get very hot. The dust was flying in, making it more unbearable. The train made stops to let us fill our canteens. After several days and nights, we began to wonder how much longer we would be on the train. We were not used to this type of heat and some of the girls became ill. After eight days on board, we reached Calcutta. More unfed people, many begging at the station. Many sleeping on the cement - their only home. We went to an Army camp and all headed for the showers. We went to the mess hall and really ate. I think it was C-rations, but after the K-rations anything tasted good.

The next day, we were on trucks again and in good spirits, singing. We headed for the plane that was to take us to Assam, on the Burmese border. When we reached Assam, we were assigned to tents, about four to a tent.

We soon learned how to get water out of a lister bag. These are long canvas bags holding water, and after sitting in the sun all day, the water is really hot. We had to put the bags in clay pots, dig a hole in the mud and keep the water down there to cool it off. It was something you only learned about in this kind of situation.

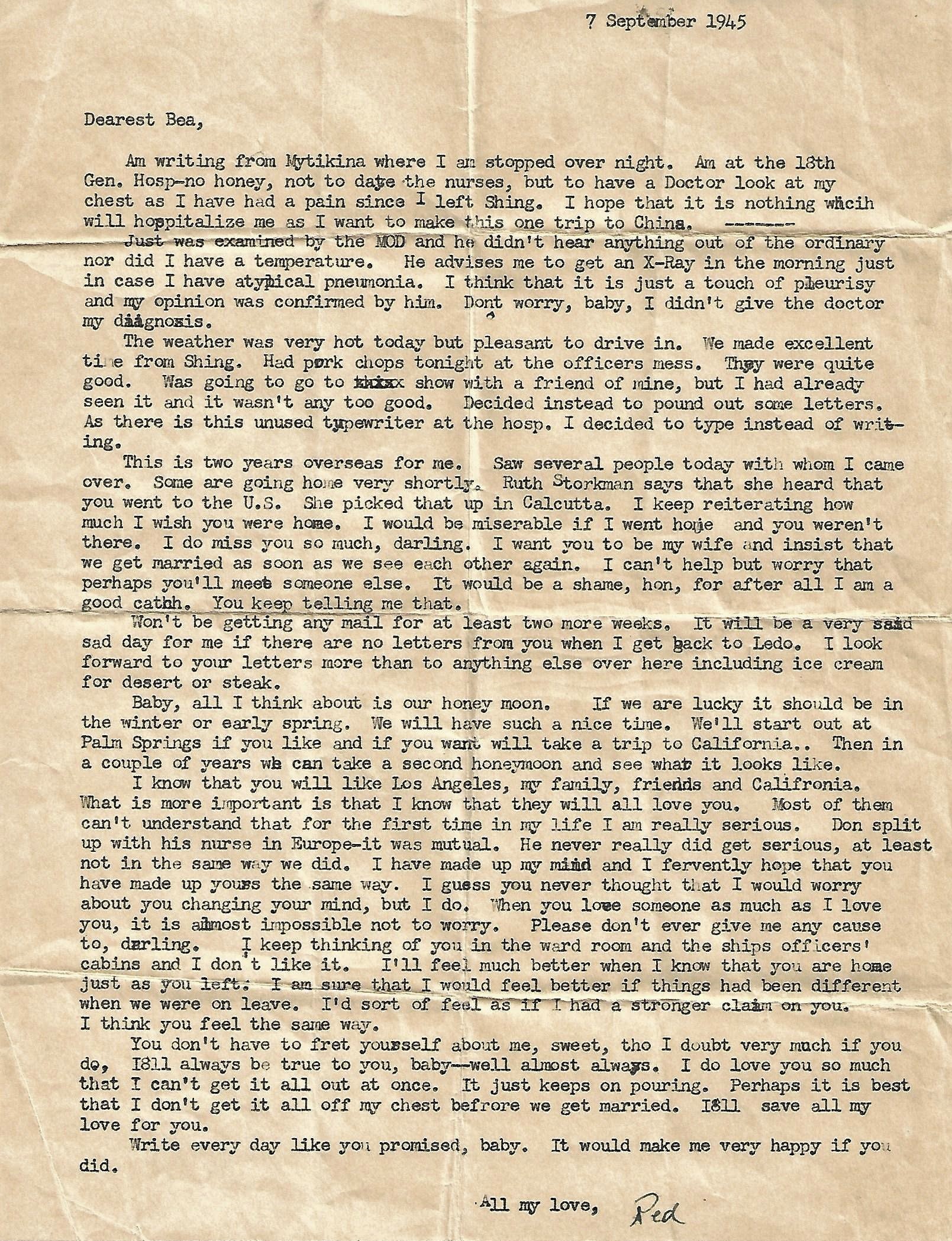

The weather in Assam is very hot. We were assigned to wards in the hospital area. These were basha huts with mud floors. So many boys with malaria, amoebic dysentery, jungle rot and wounds. How I felt for those boys with malaria, and we didn't even have a cool drink to give them. I used to sit by their beds and bathe them with as cool a water as I could get.

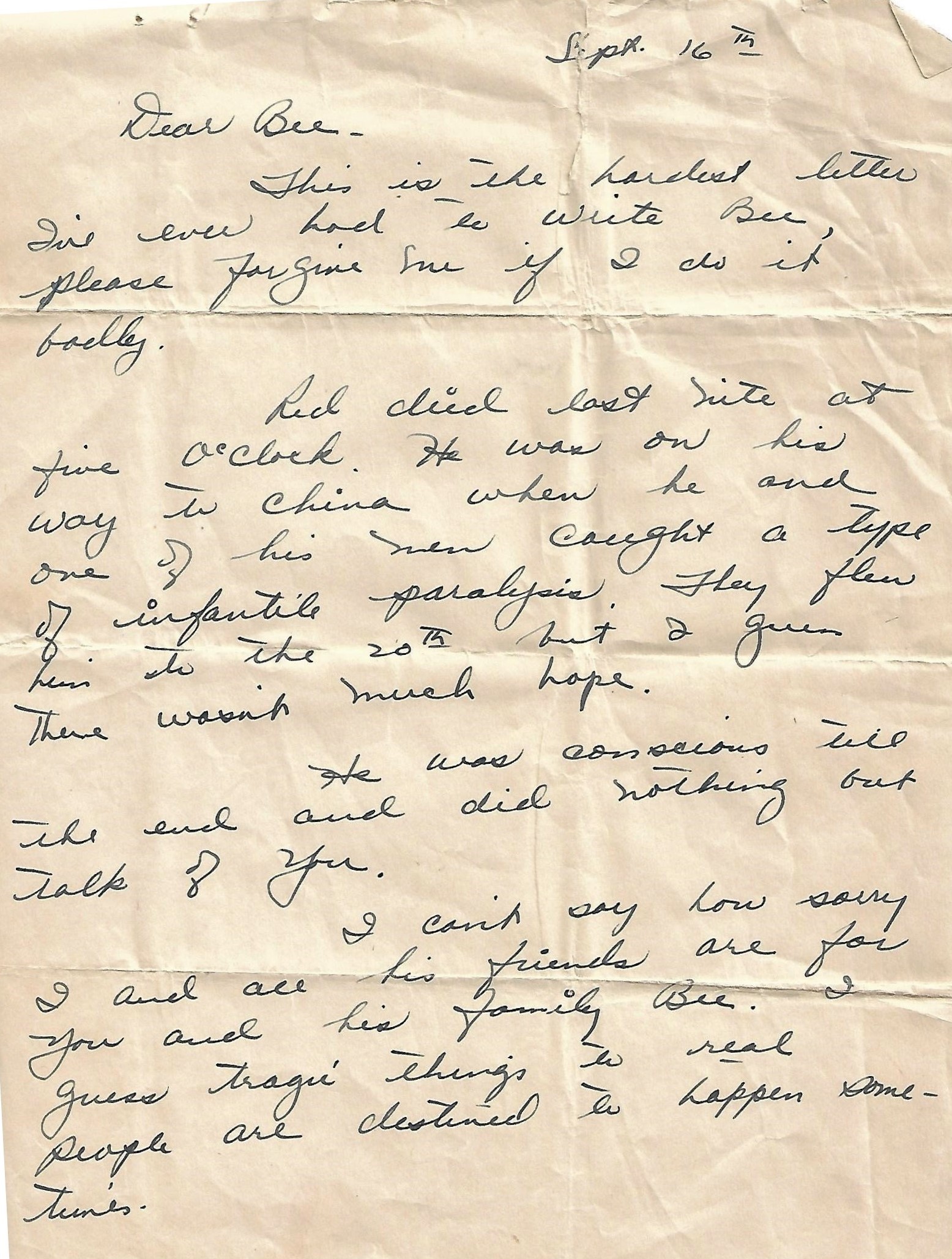

After about two months in Assam, Annie and I again got orders. This time we were going to Shingbwiyang in central Burma - a few miles from the front lines. We boarded the plane and were off again. When we landed in Burma, it was the monsoon season and I couldn't believe the terrain. Nothing but mud sliding over everything in sight. I thought, "We aren't going to live here, are we?" It was the 73rd Evacuation Hospital. Ten of us had been assigned to it.

We were taken to an area near the hospital. There was a long, narrow tent erected with ten cots that had sunk in the mud. Over the cots was mosquito netting. Our foot lockers came in with us, but most of our clothing was getting mildewed from the heat and moisture. We had seersucker uniforms and fatigue suits. The seersucker was cooler, so that is what we wore. At first, I was taken aback when I saw a huge rat run around the cot. I soon grew used to them as at night they ran back and forth over the wires that held our mosquito netting.

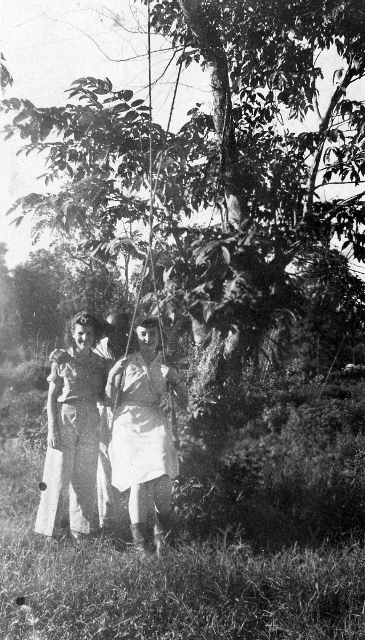

|

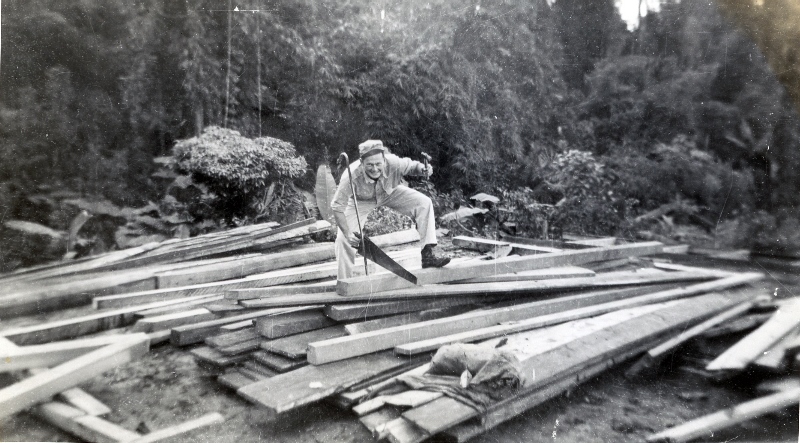

The mud was so deep that we had to wear boots and even then got stuck. Some of the boys came over and built us a helmet rack. This was about waist high and held our helmets. We used our helmets to wash in. We had a big tub to catch rain water. In the morning we would have to skim all the many insects off the top, and what insects: yellow, orange, green, huge ones and the everlasting mosquitoes. We would dip our helmets in the water and use that to bathe in. We soon grew accustomed to living this way. Then the monsoon ended and the land looked green and lush.

I was so thrilled to be in Burma, especially "on the road to Mandalay." It had always been my favorite song, and many mornings I walked down the dusty road singing it. Monkeys climbed about in the trees; you could hear elephants and tigers and all sorts of wild animal calls. We were completely surrounded by jungle.

We were in an evacuation hospital, and sent all the wounded back to the general hospital after we patched them up. I'll never forget the wounded - so many boys would go home with scars - physical and mental - that would never heal.

I had the Chinese ward, and would get cases that were unbelievable. They were at the front lines so long that their wounds were full of maggots. I remember one boy in particular who had a wound in his neck. I had to use tweezers to pick the maggots out of his throat.

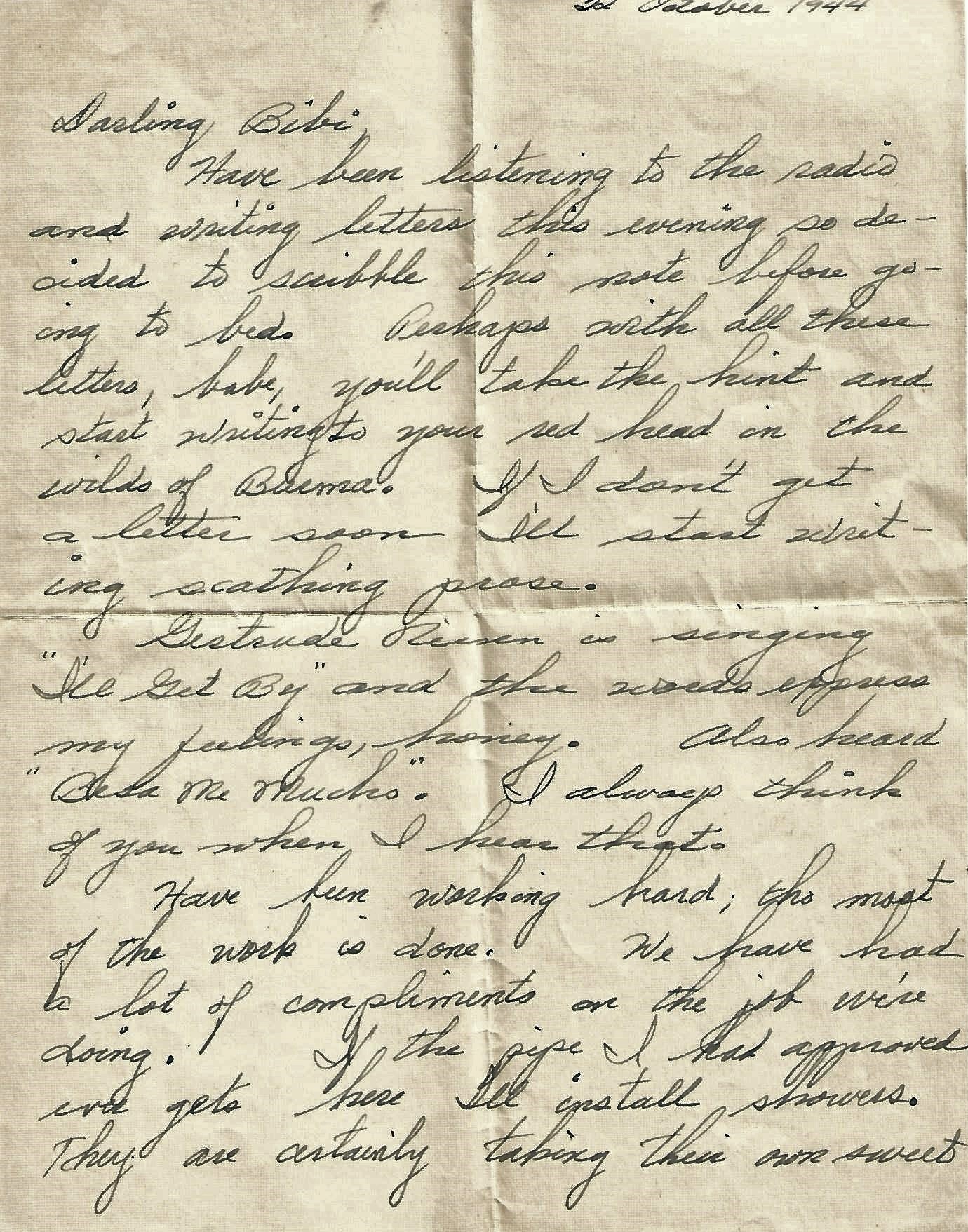

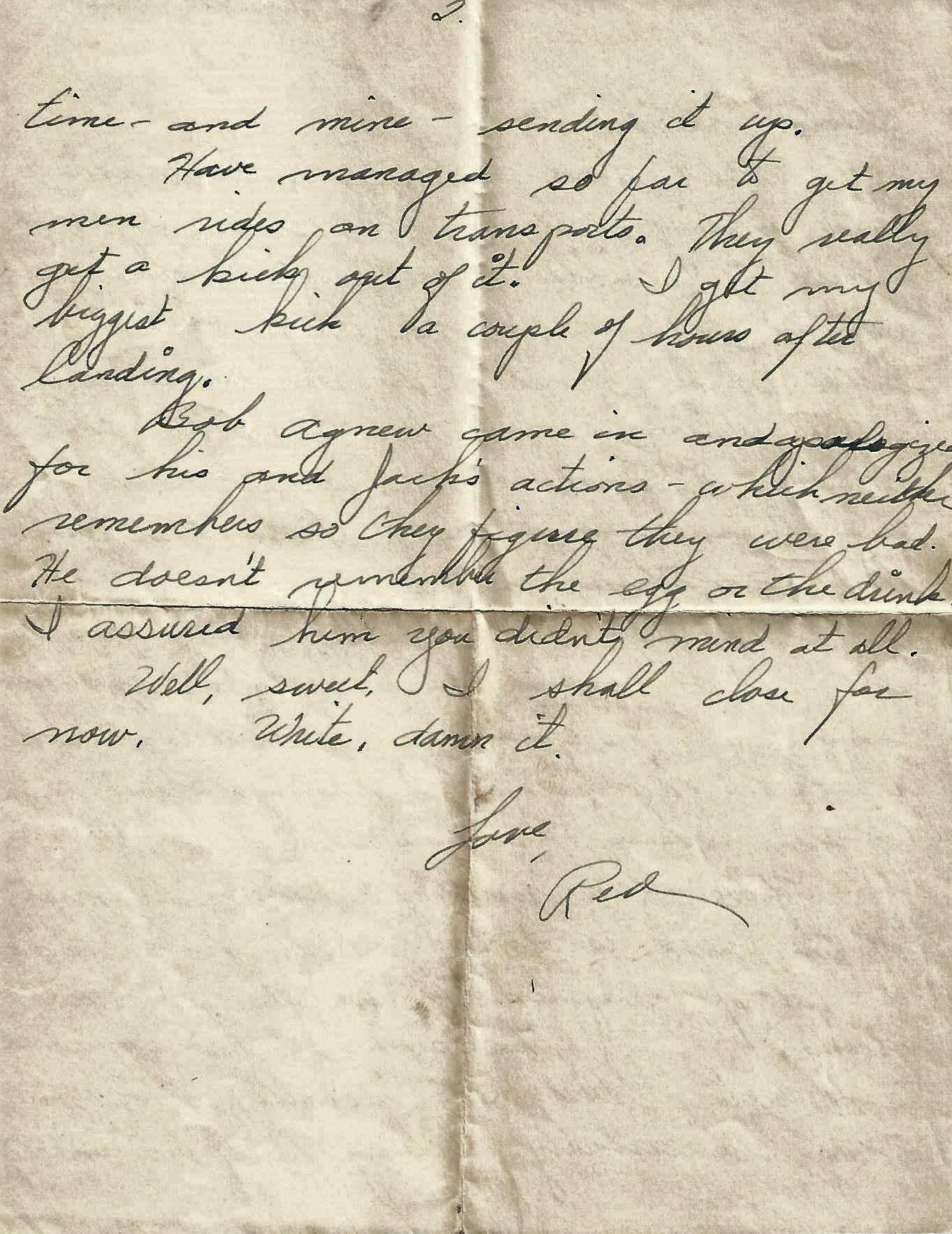

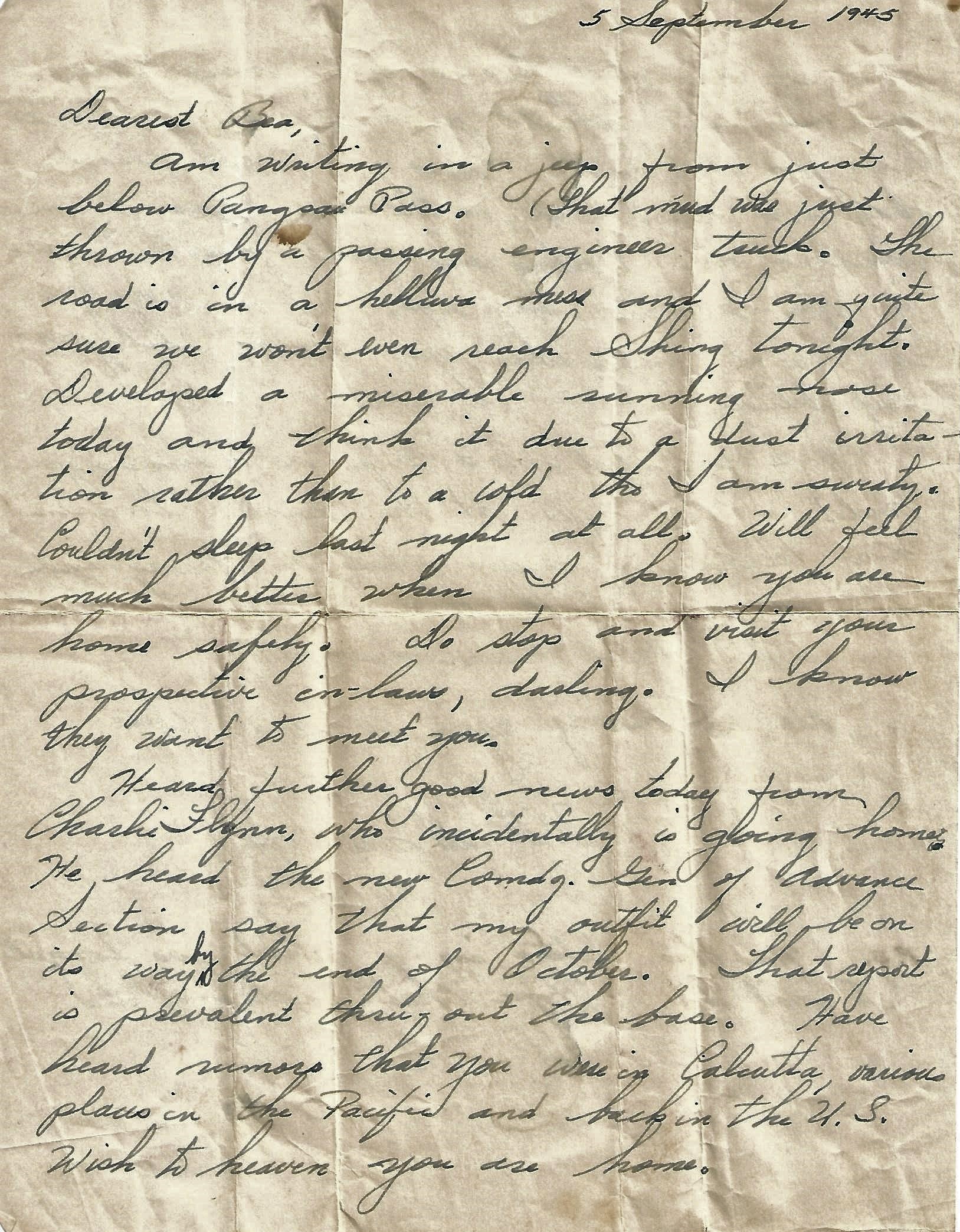

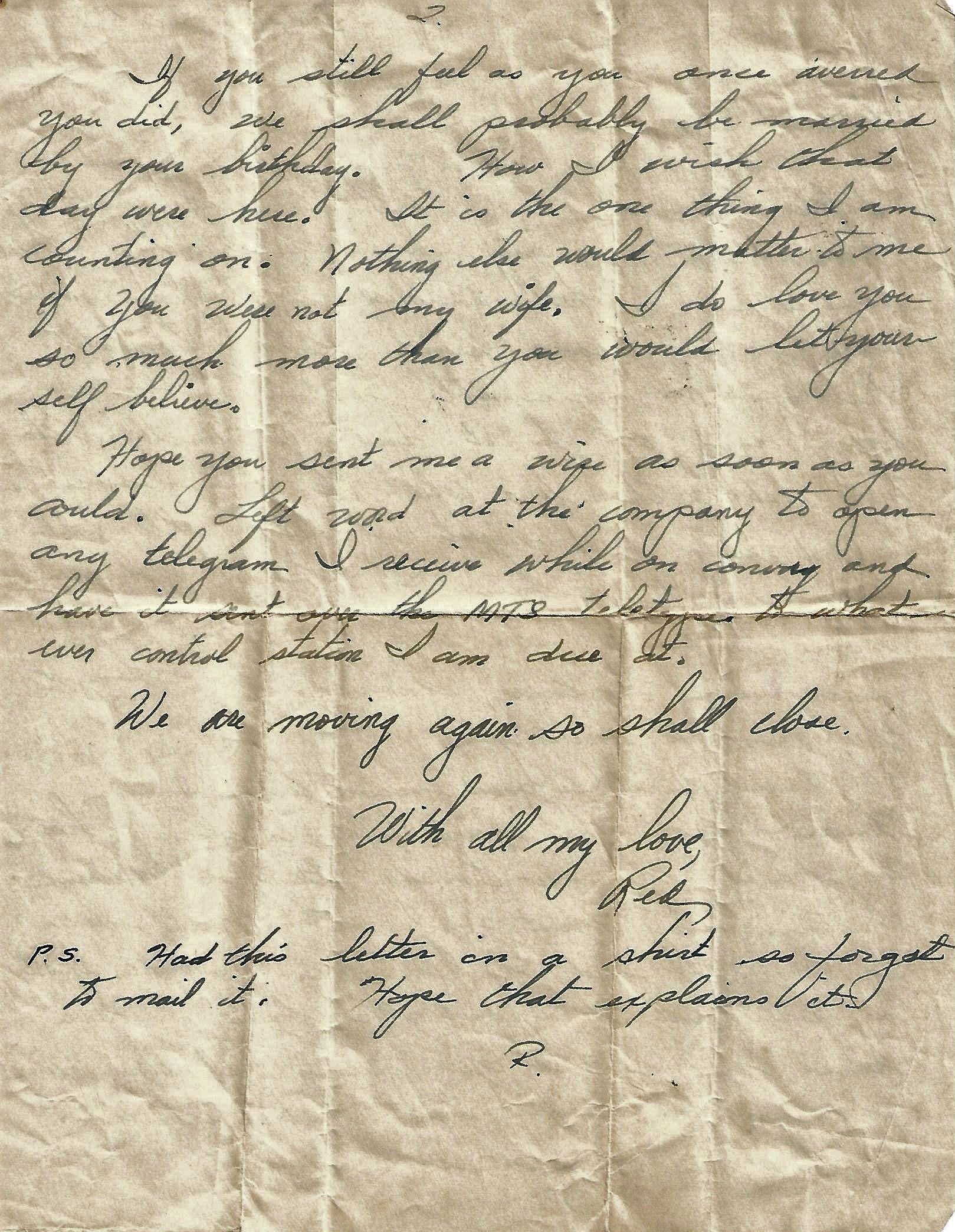

It was in this setting that I first met Red. I was sitting with my back to the tent door, working on charts, when I heard someone come in. I looked up, and there he stood. The sun was shining on his hair and he looked like a young Greek god. He spoke and it was beautiful. He sounded as if he had been educated at Oxford. He looked shocked to see me and said, "What are you doing in this God-forsaken place?" I answered, "The same as you, I guess." "I didn't know there were any nurses up here," he said.

He had stopped in to see his friend, the doctor on my ward. He was on convoy from Assam and on his way to Mindanao. That is, if the road held out. The Ledo Road going across Burma was washed out many times. Many men died of disease building that road, and right here I want to give our black soldiers credit. They built the road. It would some day, after Burma was secure, reach China.

Red pulled up a crate and sat down. We began to talk. We talked mostly of home and family. I didn't believe in love at first sight, but this was it.

The doctor came in shortly and Red and he went out to talk. My hand was shaking when I put the charts back. That evening, when Annie and I were in our tent, I told her, "I met the man I'm going to marry today. I don't know how or when, but I'm going to marry that man."

Weeks passed and my work increased - more sick and dying. I was getting weary and often thought of home. Red managed to get another convoy and came right to see me. I saw his jeep drive up and him come swinging up the hill to the tent. He walked right up, grabbed my arm and kissed me. I felt faint. We walked arm in arm over to the mess hall tent while he told me he did nothing but think of me for weeks.

We walked down the road past an old Buddha that had been shot up. While I was standing there looking at it, Red walked up and kissed me and said, "Plucky lot she cared for idols when I kissed her where she stood on the road to Mandalay." Then we recited the poem completely, both laughing as we walked along. The next day he had to leave. My heart went with him.

About a week later I was on the ward when the Chinese disciplinary officer walked in. He pointed to four of the patients and said something in Chinese. One of the boys looked to be about 12 years old. He went back in the jungle with them and lined them up. When I realized they were going to be shot, I ran out to try to stop them. The ward officer told me not to interfere. It took me days to get over it.

In a few weeks, we got orders to return to Assam. I was thrilled because I would then be near Red. Again, Annie and I packed our trunks. We arrived back in Assam and Francis, another friend of ours, had the tent fixed up for us. In the meantime, Red took another convoy to Shingbwiyang to see me. These convoys were rough duty - trucks getting stuck - roads washed out. He was frantic when I wasn't there. He didn't know where I had been sent. When he got back to Assam, he found out I was there. He rushed over. We embraced and were so happy to be together. Now he could see me every night.

We were there a few months when tragedy struck. About midnight one night, Major Camden came over to our door to tell us the plane with nineteen of our nurses had crashed. I knew Annie was on that plane. "Oh dear God, no!" I breathed, "It can't be Annie!" After all we had been through together, it couldn't end this way, but it was true - all were dead. I was so shocked over Annie that it was a few days before I realized that all the other girls were gone.

Red came running to the tent when he heard what happened. He knew how this would hurt me. At the funeral, the small band of nurses that were left stood in formation as the priest uttered the words "Ashes to ashes and dust to dust." I had to break rank and went to the side of the road and vomited. The girls were all so young. The oldest was 28. I kept thinking of their families who would receive this news.

A few weeks later, I heard from Annie's mother. "My dear little angel Annie - how will I ever live without her?" she wrote. Tears were all over the letter. For weeks, I kept seeing the faces of the girls who would never come back.

The summer wore on, and Red and I decided to take our leave together. We would hitchhike by plane across India. We got a 20-day pass and left for Calcutta. We met a friend of Red's from the states there and stayed at a good hotel. It even had a swimming pool. It had been several years since I was in a pool. It felt good.

From Calcutta we went to Gaya, the birthplace of Buddha. The heat was intense. We were stuck there for want of a plane. Finally we located a captain who flew us to Chabua. We were there a day and a night, then on our way to New Delhi. We went to see the Taj Mahal. I can't tell you how breathtaking it is when first you see that pearly dome. It's an enchanted fairyland. All I could think of was Annie. Missing this and all she would miss.

We walked about the Taj, looking in at the turrets on the side. It took 22,000 men 20 years to build. It is embedded with precious jewels and carvings. We went inside and looked at the tomb, and I thought of the man who built it for his love. We went back to see it in the moonlight, and Red took me into one of the turrets and proposed to me.

We met a few more officers who flew us to Rawalpindi. We couldn't find a place to stay that night, so we slept out under the plane. The next day we found a place to wash up and were on our way again. We flew to Kashmir.

How can I describe Kashmir? It is so beautiful. We rented a houseboat on the lake in Srinagar and swam among the lotus plants. The Nishat Bagh Garden near Srinagar is lovely. The next day our native boys took us for a ride on the lake in a shikara. Never had I felt such a thrill. It was like being Cleopatra on the Nile. They chanted as they paddled through the water. The shikara has a mattress in it and drapes from the top on either side. Real luxury.

We stayed a week, and what a week it was. We felt we would never forget it and would come back in ten years to see it again. We hated to leave, but had to get back. We were fortunate to find rides through the cities. But when I walked into the tent, there was an ache in my heart. Annie would not be there.

Red and I had a few more lovely months together until I got orders. Our company was leaving. The day arrived and we clung to each other sobbing. Red was so worried about where I was going. He said, "You're probably being sent to the Japanese invasion." He was to stay in Burma.

The trucks arrived and I climbed in back, waved to Red and we were on our way again. The ship left Calcutta on its way to Ceylon. When we were out some ways on the ocean, one of the nurses ran down and told me Red was outside in a boat. I ran to the rail and looked down. There he stood. Some of the men lowered a rope ladder and he came up. I couldn't believe it. How did he get there? He kissed me and the men cheered. We talked for a few minutes and then he was gone, waving as the boat pulled away from the ship.

I was truly amazed. Here was a guy who could do anything.

We went on to Ceylon and docked. We had shore leave and went through the bazaars. The next day, we were on our way again and the next land we saw was Australia. When we docked, the streets were full of Australian soldiers - their hats on the sides of their heads. Two of them picked me up and put me on their shoulders. They marched down the street singing "Waltzing Matilda."

Australia reminded me of the states. A group of us linked arm in arm and went to the nearest ice cream shop. I drank two malteds. Had not had one since I left.

I can't remember how long we were in Australia. I do remember it was Perth and Fremantle. Shortly though we were off again, this time to Luzon. Luzon at this time had been secured. We knew then we were headed for the Japanese invasion. I hated to think of it - more boys killed and maimed. We were in Luzon a day or two and went past Iwo Jima on our way to Okinawa.

When we landed in Okinawa, I was amazed to see the equipment. Planes as far as you could see. Trucks and tanks by the thousands all ready for the invasion. I wondered what would lie ahead.

We were taken to our compound. We found good-sized tents with room for about eight in them. Living conditions were better than Burma. By now, I couldn't remember what my bed at home felt like.

There was a party at the Officer's Club, and a real good-looking officer asked to take me and I agreed. On the way home, our jeep went over the road and down a steep embankment. I screamed for Red as it toppled over the side and down, down, we went. The jeep fell on top of us. It hit bottom and thick mud was oozing all about me. I called to the officer I was with, but he was unconscious. I tried to lift the jeep off of me but I couldn't. I lay there and began to worry. There were probably snakes around - perhaps poisonous ones. I felt my side and thought I was bleeding. After hours of laying there, a truck with some men came by. They came down and lifted the jeep off of us. I realized I was not hurt. They took us to the hospital. The officer had a broken back. I was badly shaken.

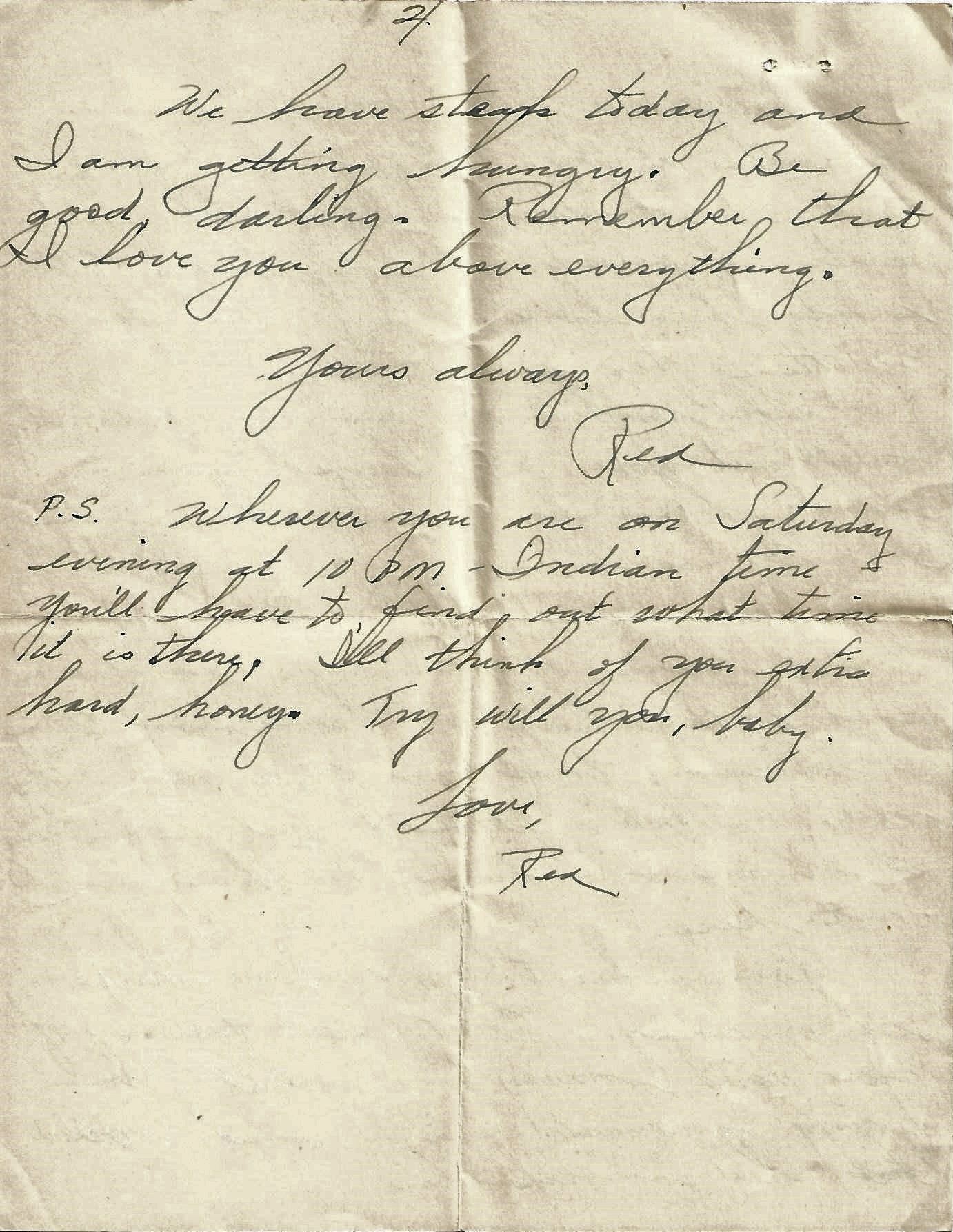

About a week went by, and I got a few letters from Red. He had not heard from me although I wrote every day. He was so concerned.

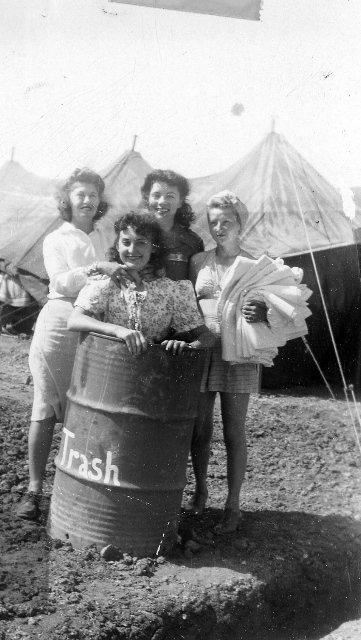

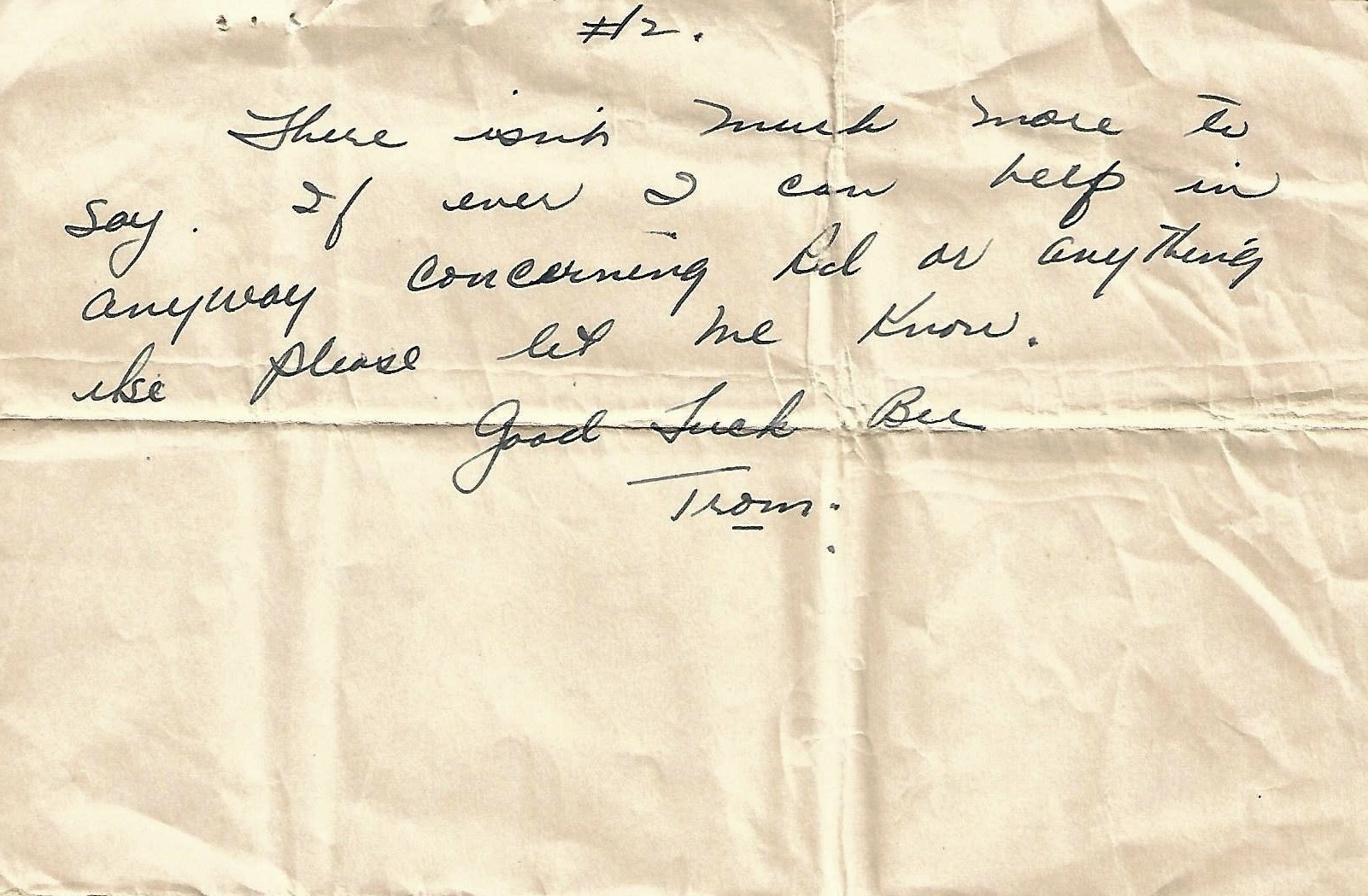

One day I awoke in the morning and someone was saying "mail call." I was expecting a letter from Red. Instead there was a letter from Woody, Red's best friend. I wondered as I opened the letter if Red had been hurt. I tore open the envelope and began to read. "Dear Bea," the letter said. "This is the hardest letter I have ever had to write. Please forgive me if I say it badly. Red died last night at 5 o'clock."

I held on to the tent pole. I felt dizzy and sick. I turned to Francis and said, "Red's dead." "How?" she said. "He died of polio." I ran to the back of the tent and began vomiting. The girls tried to comfort me, but there was no comfort.

At that time, the wind began to blow furiously, and one of the girls came to the tent and said, "We're on alert. A typhoon is headed this way." The chief nurse said to gather up only our necessities. A truck would come to take us to a Seabees lodge. The wind got worse. I hoped I would die and just sat there. As the wind grew stronger, we crawled into the truck. It could hardly stay on the road. I sat there with my few belongings thinking of Red and Annie, tears streaming down my cheeks. "Nothing left to live for," I thought.

The lodge was a huge building. We would be safe there. The Seabees took good care of us. The typhoon was major, destroying many of the ships in the harbor. 400 lost their lives. I wished it was me. I was terribly depressed. The next day we went back to what was left of our tents. It was a mess. I was sitting in front of the tent when Chuck, a good friend and ward man came up. He said, "What's the matter? You look bad." "Don't you know?" I said. "Red's dead." He looked shocked. "You're so brave," he said.

We were awaiting orders to go into Japan when something happened. It was the atom bomb. Finally the Japanese surrendered. The chief nurse called us together and said we would be going home. Everyone screamed and yelled with happiness. I walked between them like a ghost.

In a few days, we were packed up and ready to leave. The Army trucks picked us up and the girls sang the old Army songs all the way to the ship. A landing craft came ashore and picked us up. As the door to the craft came up, it was like the end of a book. The landing craft headed for the ship. We climbed the ropes on the way up. I imagine we were a pretty scary-looking lot. Our skin was yellow from the drugs we had taken for malaria. Many of us were thin. Some of the girls had dark circles under their eyes. The years overseas had taken their toll.

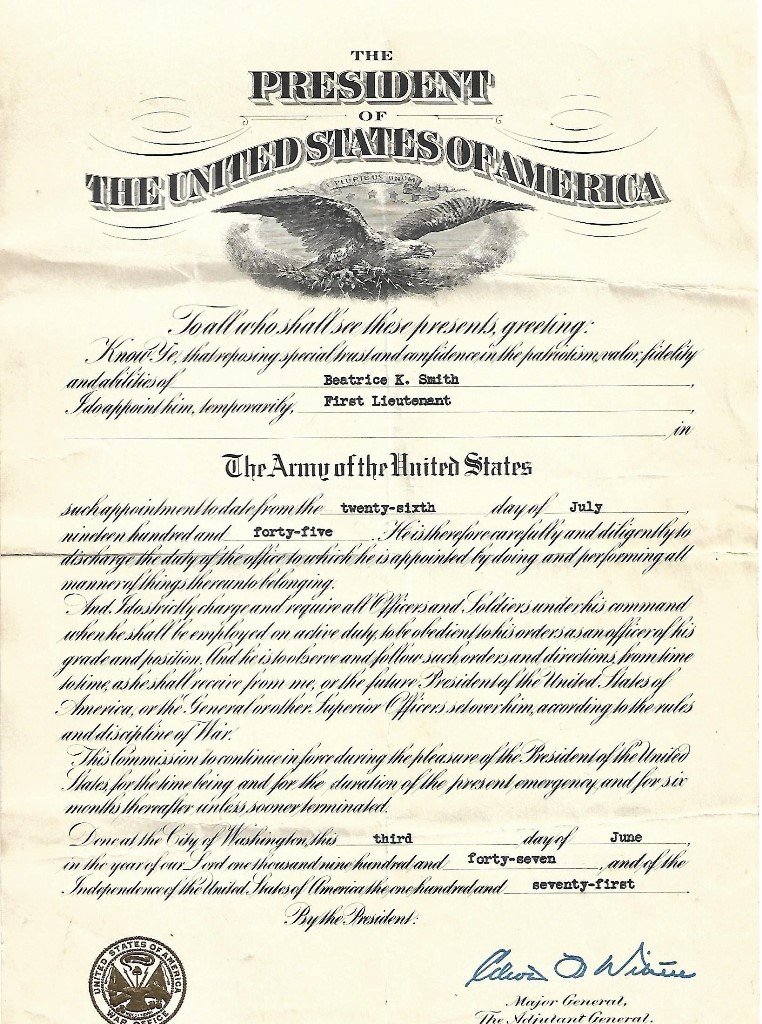

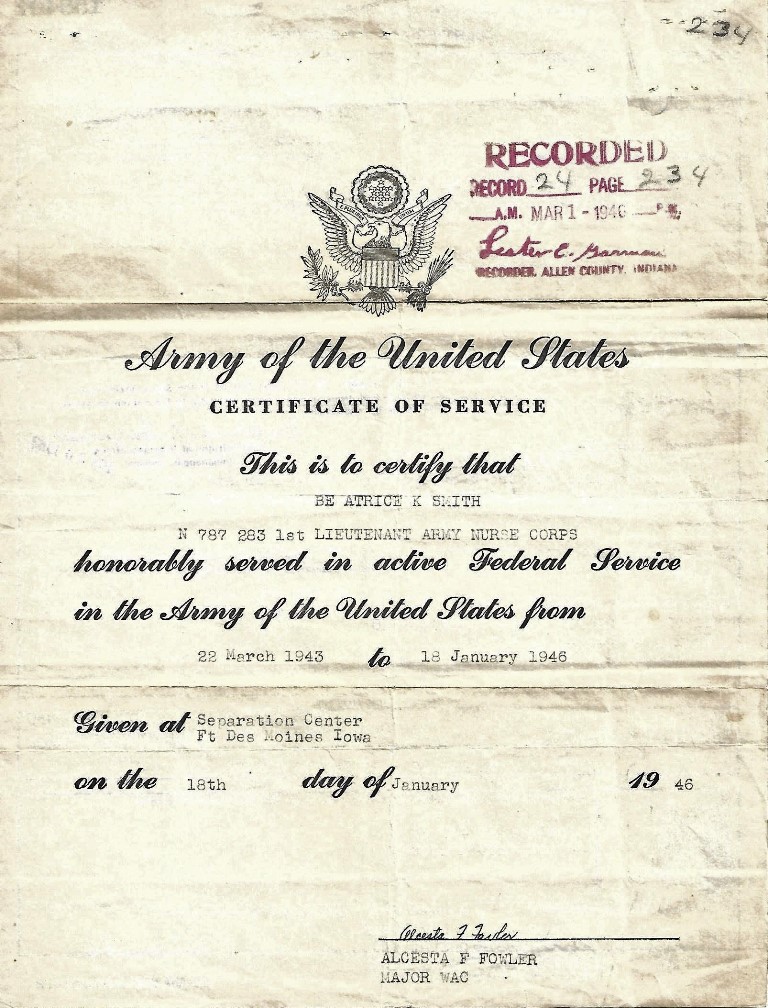

We headed for the states and arrived in Portland, Oregon. I can't describe the beauty of the Columbia River. It was fall, and the foliage was sheer beauty. We were at Portland a few days and then went to Des Moines, Iowa. We were discharged from there.

The last day, I went out on the porch of the barracks. A breeze was blowing and I heard taps playing. It was the end. My Army days were over and I would never forget. I look at the young people today and I know they don't realize the sacrifice many of us made to keep this great land of ours secure. And whenever I hear the Star Spangled Banner, I look at the stars and stripes and think of all the boys and girls who died, especially Annie and Red.

© 1983 Beatrice Tourin