|

|

|

By Sgt. DAVE RICHARDSON

YANK Staff Correspondent

WITH THE FIRST CONVOY TO CHINA OVER THE LEDO-BURMA ROAD - The celebration on Pfc. Oscar Green's 21st birthday was the biggest in his life.

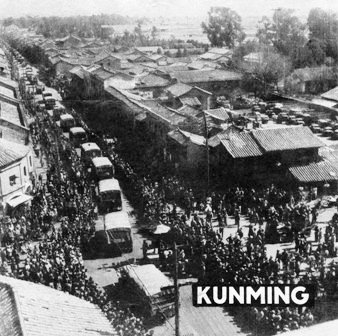

Green drove a jeep in the first motor convoy in history from India to China. The day the convoy reached its destination at Kunming was also Green's birthday and although the Chinese people had never heard of Pfc. Oscar Green, they did know one thing: The convoy had ended a three-year blockade by the Japs of the land route to the Orient. So the people put on the wildest celebration in their eight years of war. And not until then did I notice a change in Pfc. Oscar Green.

When I had started out from Myitkyina, Burma, in Green's jeep he muttered "To me this is just another dirty detail. Damned if I don't always seem to catch 'em." All through the trip he had stuck by that belief.

"Who likes sleepin' on the ground? he would ask. "Or cooking his own meals, or driving from dawn to dusk day after day, or getting wind burned an' chapped and covered with dust? I sure as hell don't."

Then, on Green's birthday, our jeep finally swung through the narrow streets of war-swollen Kunming at the end of the 1,000-mile journey, and Oscar took in the scene. There were thousands of Chinese - some wrinkled with age and some tiny kids, a few of the wealthy in fine clothes and an overwhelming number of the poor in tattered rags. They lined our path for miles, scanning the long procession of new vehicles, waving banners, shooting off firecrackers, grinning, clapping and shouting. For the moment, Green dropped his cockiness and cynicism. He grew silent. When he spoke again, he was dead serious.

"Ya know," he admitted grudgingly, "You been hearin' me bitch ever since we started. But now that it's all over I guess I was wrong - in a way. I'm sorta glad now I made the trip, 'cause somehow I feel this thing is gonna go down in history."

Most of the rest of us in the convoy went through the same transformation as Oscar Green. Although some of us began to realize the significance of what we were doing before others we were backward about saying so; afraid of being laughed at.

This was more than just a long drive over dusty roads. This marked the closing of one chapter of the war in the Far East and the opening of another. Thousands of Chinese, American, Indian and British soldiers had fought, worked and died in Burma and China to make this trip possible. Maybe the reopening of the land route to China and the start of the convoys over it wouldn't change the course of the war in China in a month - or even six months - but the ultimate effect, we felt, would be victory in the land that had fought the Japs for eight years.

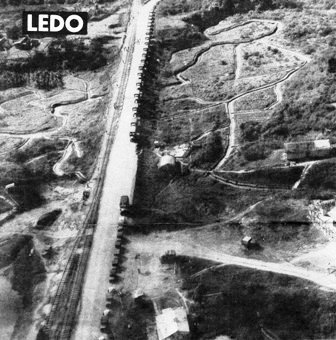

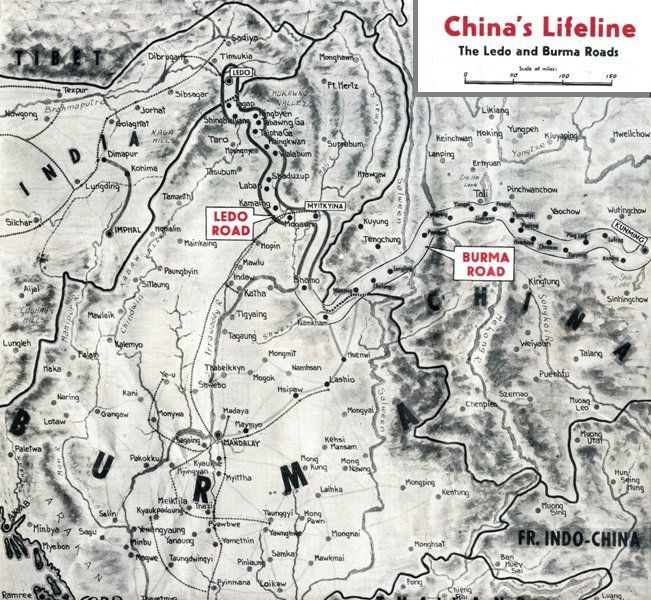

The convoy rolled out of Ledo, in Assam Province of India, even before the last Japs had been completely cleared out of the Shweli River Valley - last link in Northern Burma between the Ledo and Burma Roads. Three days and 260 miles later the vehicles pulled into Myitkyina - biggest American base in Burma -and waited. After a week, the convoy got the go-ahead from Lt. Gen Dan I. Sultan, Commanding General of the India-Burma Theater, who announced that the last pockets of resistance were being mopped up.

We got up in the darkness the next morning, dressed with chattering teeth, drew 10-in-1 rations, packed our bedding and equipment in the vehicles and gathered at the push-off point. There in the grey dawn were nearly 100 vehicles of all sizes, some with artillery pieces hooked behind and some loaded with supplies.

At 0700 hours Brig. Gen. Lewis A. Pick of Auburn, Ala., who had directed most of the Ledo Road construction and was to lead the convoy, called the GI drivers together for a last-minute meeting.

"Men," he said, "in a few minutes you will be starting out on a history-making adventure. You will take this first convoy into China as representatives of the United States of America. It's up to us to get every one of these vehicles through. Okay, start 'em rolling."

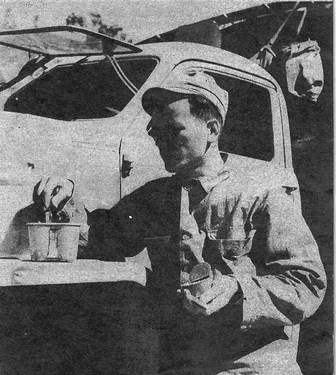

As I got into jeep No. 32 with Pfc. Ray Lawless of Brooklyn, a photographer for the Signal Corp. I noticed that a Chinese driver was climbing into the cab of every truck as assistant driver. Other Chinese soldiers, veterans of the Burma campaign, were boarding six-by-sixes to serve as armed guards.

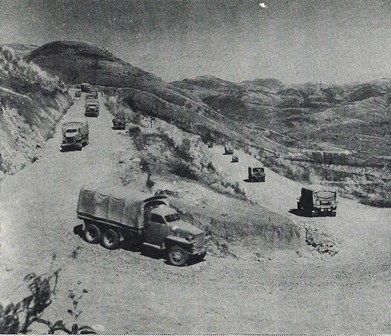

By 0730 the parking lot was filled with the noise of engines as vehicles rolled out, turned onto the Ledo Road and headed south through the early-morning mist. There were motorcycles with MPs, jeeps and quarter-tons, GMCs and Studebakers, ambulances and prime movers. A handful of officers and GIs and a lone nurse had arisen early enough to see us off.

THE CONVOY started slowly down the broad dirt road, with vehicles spaced at wide intervals in case of an air attack. As the trucks rumbled across the Myitkyina ponton bridge, spanning the Irrawaddy River, P-47s of the Tenth Air Force and two tiny L-5s containing photographers roared overhead.

The convoy thundered along, stopping only for K-ration lunch, as we passed American Engineers on bulldozers and graders, Indian soldiers digging drainage ditches and Chinese Engineers building a plank bridge. During the Bhamo battle the road had been nothing more than a narrow, rutted one-lane jeep trail, but now it had been widened and packed hard.

Fifteen miles from Bhamo we came upon a macadam highway that had been built before the war and by late afternoon we were pulling into a bivouac area. GI tent camps had sprung up all over Bhamo in the month and a half since its capture.

We unpacked our bedding rolls, some of the GIs stringing up jungle hammocks between vehicles and some putting their sacks on the ground. Then we cooked supper over gasoline stoves in groups of two or three and went to sleep early.

The first night's bivouac area was the same place I had been with a Chinese regiment during the 32-day siege of the city. As I dozed off, I kept thinking how quiet this spot was compared to the last time I had been here, when tracers, whistling shells and mortar bursts filled the night air.

Next morning at dawn we were off again in the morning mist, by-passing a knocked-out bridge and soon plunging into the jungles and hills, following the ancient spur road that had first been used by foot travelers in the days of Marco Polo and before the war as the main route for supplies from Rangoon that were shipped up the Irrawaddy River be boat to Bhamo, then transported over the spur to the Burma Road and thence to China. More vehicles had joined us at Bhamo, bringing the number in the convoy to 113.

By mid-afternoon the convoy descended from the hills into the fertile open country of the Shweli River Valley, entering Namhkam, which had been captured by the Chinese 38th Division only nine days ago. Before we get all the way through the battle-scarred village, an officer halted the first jeeps.

|

|

"Looks like you'll have to lay over here for several days," he said. "The Japs still hold several miles of the road ahead. In fact, some of them are right up there in those mountains - five miles away - with artillery, and they can see every move we make. They forced our artillery out of one position yesterday with their 150s."

The convoy went a few miles past Namhkam and pulled into a wooded area that had been a Jap strongpoint a few days before, with cleverly concealed emplacements everywhere. Unpacking, we could hear the dull thud of Jap shells miles away and occasionally the slam of Chinese mortars. The drivers were wide-eyed, for this was the first time most of them had ever been so close to the enemy.

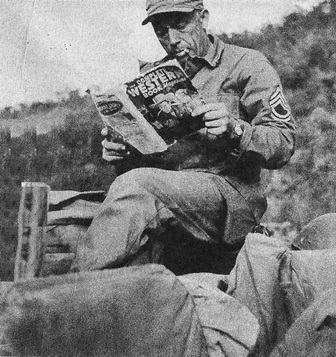

While everyone lolled about the next day, I went around and talked with some of the drivers. All the GIs said they are members of QM trucking companies. Like Green, who hails from Taylorville, Ill., most of them come from little places such as Ada, Okla.; Imlay City, Mich.; Oakland, Ind.; Oconto Falls, Wisc., or Pipeville, Ky. Their favorite movies are Westerns like the Hopalong Cassidy series and they would rather read Thrilling Western Stories than most of the more popular publications. They admitted that they get as much kick out of spinning the wheel of a big GMC truck around a mountain ledge as a fighter pilot gets out of buzzing a field.

The most veteran of the GI drivers are the Negroes, who have been piloting trucks over the Ledo Road for from 18 to 24 months. In fact, 90 percent of the convoying on the Ledo Road for more than a year was done by Negro drivers.

"Them monsoons was the toughest part of it," said T/5 Wilbur T. Miller of Tupelo, Miss. "Last summer, for example, there was several feet of water in some places, deeper than our hub-caps. The whole road was sometimes just a sea of muck. The rain used to cave in a couple of tons of earth on the road in different places every week and all we could do was set there waiting till the Engineers could shovel it off. Once some colored boys I know was stranded for a week by these here cave-ins and the muck. They slept and ate right in their trucks. And boy, that ain't fun!"

IN THEIR months of convoying from India to combat bases in Burma, the GI drivers have developed a slang all their own.

"I'm what's known as a 'cowboy'" Green explained, when I remarked at his fast driving and his taking chances that had me gripping my seat. "I'm also 'gas happy,'" he continued. "That means I gotta go fast; I hate driving slow."

Another driver said Green was just being modest, for he was a "cockpit driver," a GI who out-cowboys the cowboys of the road. He also has a reputation for "cuttin' it," or driving fast around mountain curves; "waving his back wheels," or passing another truck and leaving it far behind; and keeping his "foot in the gas tank," which is speeding.

Highest praise from one driver to another is to say "He's sure gettin' 'em!" which means he's shifting his gears perfectly in a big truck, especially when it's on a hill. A good driver is one who can "top it," or get over a grade without having to shift gears. One trick for doing this is to speed up going down a hill so the next hill can be taken without shifting. "Bootin' it" is driving along at a steady mile-eating pace.

Occasionally a driver has to "tank one," or drive a truck into a bank when it goes out of control in the mountains. As a last resort, such as when the wheels lock on a mountain ledge a driver may have to put her down" - abandon the truck and let it tumble into the gorges below.

The Chinese assistant drivers, who later were to take over the wheels for the last few miles into Kunming, are also veteran drivers. Fifty of them were Burma Road drivers before the war. Three and a half years ago they were bombed out on the way back to China when the Japs overran Burma. They have been convoying in Burma ever since, once running into some Japs and winning official commendation for getting rid of them with tommy guns.

"That word 'cowboy' applies to these pings, too, as any GI driver will tell you," said Maj. James B. Griffith of Houston, Tex., who has been their liaison officer.

While we stayed at Namhkam waiting for the last Jap resistance to be cleared, Lt. Col. Gordon S. Seagrave, author of the best-selling book, "Burma Surgeon," returned to his peacetime hospital with his medical unit three years after leaving Namhkam to walk out of Burma in the retreat with Stilwell. His unit, with American and English officers, GI and Chinese technicians and Burmese nurses followed the Chinese advance back into Northern Burma for two years, treating thousands of wounded, before arriving back at the big stone hospital at Namhkam, now partly demolished by bombs and shells.

To mark the home-coming, native tribes for whom Dr. Seagrave had been "family doctor" for 22 years swarmed out of the hills. They prepared a huge feast, invited everyone in the vicinity and put on their dances and sang their songs. Several GIs from the convoy were there and one or two even got into a Kachin ceremonial dance that night. "It's almost like the Conga," they said.

|

There was a flurry of excitement in the bivouac area next afternoon when a Jap rifle cracked and the bullet whined overhead. Everyone scurried for cover and soon several weapons opened up - Jap, Chinese and American - but the firing stopped after a few minutes without anyone getting it, including the hidden sniper.

On our fourth afternoon in Namhkam, Gen. Pick got a message that American-manned General Sherman tanks had spearheaded a final Chinese breakthrough along the road to the Burma Road junction, so next morning we were off again.

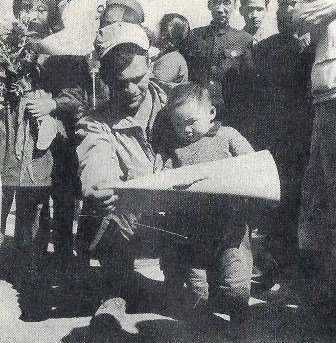

Within two hours the convoy arrived in the village of Mu-se where the last big battle had taken place, for a celebration. Into the levelled town came troops of the Chinese First Army and those of the Chinese Expeditionary Force, which had driven through from Burma and China over the last six months to clear the Japs away from the Ledo and Burma Roads.

The two armies were a strange contrast. The soldiers of the First Army who had fought in Burma wore suntan uniforms, GI helmets, British packs and carried Enfield rifles, and tommy guns. They looked plump and well-fed. But the pings of the CEF, who had fought through from China, wore everything from ragged and patched blue uniforms to clothes they had stripped from the bodies of dead Japs. Only one man in every squad seemed to have a weapon - usually an ancient German rifle or a Jap Arisaka - and all of them looked half-starved.

|

The difference between the two Chinese armies was the difference between the extensive air and land supply lines in Burma and the blockade of the land route to China that made it impossible to deliver trucks, uniforms, weapons and equipment in sufficient numbers to equip thousands of men when even gasoline for the Fourteenth Air Force had to be flown across the Hump.

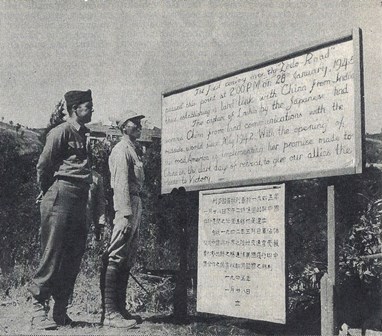

From Mu-se the convoy wound through barren hills to Mongyu, rolling onto a macadam highway at a right angle to the road and passing a signpost that had just been put up at the intersection saying: "Junction - Ledo Road - Burma Road." Just 20 hours before the tanks had broken through, and now a convoy to China had, for the first time in three years, arrived at the Burma Road. But we didn't stop. The trucks swung left, passing more ragged single-file columns of the CEF as we headed for the China border.

ON TOP OF a hill 10 miles from the Ledo-Burma Road junction the vehicles halted and drivers were ordered to put Chinese and American flags and read, white and blue streamers over their hoods. The convoy started slowly down the hill and halted near an open field in which were thousands of Chinese and American soldiers and a platform containing more high American and Chinese generals than have ever been on any stage together in the previous three years of the Asiatic war. After speeches and band music, Gen. Pick's jeep drove through an arch that was decked out with garlands of leaves and signs and ribbons. Behind the arch was a short wooden bridge over a muddy stream. This was the Burma-China border. The vehicles crossed the bridge and continued on through the border town of Wanting to bivouac near Chefang.

For the next two days the convoy thundered through places that had been battlegrounds of China during the last six months.

The road wound thousands of feet up into the Kaoli Kung mountains which are part of the Hump on the air route between India and China. After hours of threading our way along narrow mountain ledges, we came around a bend to see below the blue ribbon of the Salween River which had been the Chinese line of western defense for two years until the CEF offensive began last May. As the first jeeps reached the river, American antiaircraft men guarding the river leaped to their guns.

"Two-ball alert," one of them told us. "Thirty-one Jap planes spotted 100 miles due east. What a target this convoy would make, bunched up in the gorge like this!"

He said the Japs had tried to destroy the bridge twice in the months he had been there, but each time they missed. The bigger trucks had antiaircraft machine guns mounted on them, and the gunners swung them up. But after half an hour the "all clear" sounded and the convoy pounded across the suspension bridge to begin another climb into the mountains.

That afternoon the convoy came out of the hills into Paoshan. A Chinese Army band blared as we rolled toward the city gate. School children waved banners, firecrackers cracked and signs were plastered everywhere welcoming "Commander Pick and his Gallant Men" and "Moe Munitions and All Kind Materials." That night there was a big party in a Confucius temple for the whole convoy. There were more speeches, an elaborate Chinese meal, acrobats and gombays.

Except for the difficulty of trying to eat with chopsticks, the gombays gave the GIs the most trouble. Gombay is a Chinese word meaning "bottoms up" and three or four gombays with small tumblers of rice wine (called jingbao or "air raid juice," by GIs stationed in China) which tastes like wood alcohol, can be as powerful as a whole case of beer. Nevertheless, the Chinese at the party were proposing toasts every 10 minutes, and the GIs in their desire to be as diplomatic as possible, were soon feeling no pain.

Next day, although nearly everyone got up feeling shaky from the night before, we made the longest day's trip of all - 150 miles through rice paddies and up into the mountains again. Finally at 1900 hours that night the convoy halted in an open field. As we fumbled around with our flashlights to get our gasoline cooking stoves going and put down our bedding rolls, a GI nearby started beefing.

"Why the hell is it," he asked, "that every time we bivouac - except for last night when we slept on a cement warehouse floor - we always have to do it in an open field on the highest and windiest spot in miles?"

As it turned out, the next three nights were to be spent the same way. We had all brought jungle hammocks along, but in open fields the only place to string them was between trucks or guns or jeeps. Most of us just laid our blankets on the ground. This particular night was so cold that when we awoke next morning frost was over everything. Lawless had to use our gasoline stove to melt it on our windshield.

The convoy pushed through Yunnanyi and another celebration to camp, as usual, on a high windy spot about 20 miles away. Several GIs were in the streets of Yunnanyi to greet us and one of them held up an empty beer case and yelled, "Where's the beer? We got two cans this month and four for December." Immediately others started yelling the same thing. It appears that this is a stock question asked by American soldiers in China. The closer we got to Kunming the more we heard it.

|

|

TWO DAYS from Kunming as we passed the highest point on the Burma Road, elevation 9,200 feet, and Lawless, beside me in the jeep, cracked, "I wonder how come they didn't pick this for a bivouac area?"

Again that day the convoy whirled through village after village that had erected arches and signs and turned out to see us.

Eleven days after leaving Myitkyina, shortly after passing our first Chinese factory - a salt plant at I Ping Lung - and coal mines nearby, we found ourselves pulling into bivouac, at the 16-kilomater mark, above a broad lake. It was named Tien Chih, and across it we could make out the sprawling city of Kunming. Next day, Gen. Pick announced the convoy would enter the city.

That night happened to be the worst of all, for a heavy rain started slanting down around midnight, soaking us and most of our personal equipment. The next morning we put away our dust-covered fatigues, dug our wool uniforms out of barracks bags and dressed for the last and biggest celebration of all. "This Kunming must be a chicken place," said Green. "We even gotta put on ties. Again the Chinese and American flags and streamers were put on each vehicle. Gen. Pick called the GIs together.

"I am proud of you men," he said. "You have brought every one of the 113 vehicles through safely. I am going to see that each of you drivers gets a letter of commendation."

The Chinese drivers climbed behind the wheels for the first time and the convoy moved past the 15-kilometer mark to its destination. We were all tired, our clothes were still wet from the night's rain, our lips were chapped and our faces and necks were red with wind burn. We all knew what to expect - more crowds and signs and arches and banners and speeches and parties. Beside me in the jeep, Oscar Green was quieter than usual.

For one thing he had been feeling pretty sick, so sick that we stopped our jeep the day before at a hospital along the road for him to get some pills. When he came out he said they wanted to keep him there because his temperature was over 100. But he refused to let Lawless or me tell anyone about it for fear he wouldn't be allowed to finish the convoy. The other reason he was so quiet was that he had been figuring something out in his mind.

"They asked for volunteers among the drivers to fly back to Ledo tomorrow instead of hanging around Kunming a few days and rest," he said. "And I told 'em I wanted to go. I wanna get behind the wheel of a big ole GMC and really boot it. This convoy is too much of a circus with all this celebratin', but I betcha we can make it in eight days next time, instead of 12."

"Happy birthday, Oscar," I said, as the first convoy in three years over the land route to China rolled slowly towards the 0-kilometer mark.

|

|

|

China has been waiting a long time to give this welcome but when it came at last, it was given to only a few of the GIs who had made this day possible. The Engineers still working on the Ledo-Burma Road, those who were replaced and those who died, did not see China's people line the streets of Kunming by the thousands when the convoy rolled in.

Today's scene (this is February 4th) will have to be pictured to the absent Engineers through the eyes of those who represented their units. Ten of them rode with this convoy.

The Ledo Road is not the sole accomplishment that made this climatic day. It is only a part, but the portion stands as an equal alongside the other ventures and campaigns launched in China, Burma and India. The British had once given up construction of the Ledo Road as an impossibility. Too much mud, too much mud were the words drummed into ears of those who had given it up and into those who still looked for a way to complete the line.

British Engineers started their part of the construction from Ledo and were to work south and eastward. The Chinese began their part of it from the Mogaung Valley and were to work to the north. With speed and a three-directional effort such as this, there was a good chance for the Myitkyina-Ledo link to be realized.

The Chinese part of the plan collapsed with the Japanese occupation of the sector of Burma from which Chinese coolies were to clear a way for the road. Available equipment and manpower fell below the needs of the British, forcing them to abandon the attempt.

A renewed effort on the Ledo Road was placed in the hands of Gen. Stilwell. On December 1, 1942, American Engineers started all over again. Mud and rain had often taken away what was once completed. Sickness from Burma's relentless damp weather and malaria put 80 percent of one Engineers company in the hospital.

|

No more equipment had come and there was still the same shortage that held up the British. Native workers were hired on a time-stipulated contract. When their time was up, they quit and went back home. Others had to be found and all that were found couldn't be hired. Some refused to be taken too far from their village homes so if they could be persuaded to work, they had to be placed where they would be satisfied to labor.

Men were lost through freak accidents and through the natural hazards of such a construction job. Once a dynamite dump blew up. Monsoon weather had bogged down trucks, leaving no way for rations to get to the men. One of the Negro engineers was drowned while trying to save a companion GI foundering beneath a ponton bridge.

Some men were lost on the Tanai River which was used to haul supplies. They had been picked-off by Jap snipers. Another Negro engineer died trying to save his white buddy. He was burned to death when he tried to pull the GI out of a burning powder truck. Some outfits worked so close to the enemy they were peppered by mortar and artillery fire.

Two of the Combat Engineers with this convoy had seen action at Myitkyina, the battle which has been recorded as the most murderous in this part of the world. Representing one was T/5 William G. Snell of Wichita Falls, Texas, and speaking for the other battalion was T/5 Chris J. Owens of Bristow, Okla. They were part of the outfits that had been pounded by the Japs for 65 days.

A week after they had beaten out the Japanese, these Engineers were back working on the road again. When relief finally came around they were flown back to India for a rest of six weeks but when that vacation ended they returned, this time right behind the Chinese infantry. They put in combat roads, built bridges and helped improve a road that had already been in use beyond Myitkyina.

"SEEN ACTION in Myitkyina" is a very light way to phrase the experience of these men. Before they fought here, they had been in the theater only six months, the only combat troops around at the time. They were replacements for the exhausted, shot-up Merrill's Marauders. When they rejoined the Chinese to go on with building the road, they had to move their camp seven times in three months to keep pace.

All of this time - nine months for Owens' outfit and five for Snell's - they were under Jap shell fire. Other "representatives" on this convoy were Lt. George A. Smith of Port Arthur, Tex.; S/Sgt. David C. Anderson of Foresight, Mich.; T/5 Arthur T. Lewis of South Easton, Mass.; T/5 Edgar W. Moore of Dodge City, Kans.; T/5 William Moerk of Chicago; T/5 John R. Robinson of Mannington W. Va., and T/5 George J. Shimkus of Racine, Wisc.

The large number of Aviation Engineers working on the road might be surprising to some, but it wasn't to the GIs who belonged to these units. They came expecting to abandon whatever they learned about airstrip construction.

In the first 10 months, the Engineers had poked this road through 42 miles and had nudged another 62 miles to Shingbwiyang before the job had eased off any at all. In the next 15 months their work practically slid along. More men and equipment came in. A semblance of a road was already cut through but it needed improvement. Brig. Gen. Pick took command of the Ledo Road project and Lt. Col. W. J. Green of Rockford, Ill., was named Road Engineer. With new equipment and the added manpower they finally connected the Ledo Road with the old Burma Road at Mongyu.

"This has been a much tougher deal than the Alcan Highway construction," says Col. Green, "for, although the Alcan is a lot longer, this job was completed under the most severe weather conditions, with more physical hardship and less men and equipment."

There were repeated setbacks caused by fierce monsoon weather and smashing electrical storms that hit in the Hukawng Valley, the wettest spot in Burma. In one month of the 1943 monsoon (which starts around June and ends in September) the Engineers could account for only three miles of road. Then they had to scratch that off the books after landslides and cave-ins took that little bit away from them.

Sixty percent of the work was done by Negro construction battalions. One such regiment and a white battalion acted as "point battalions" in cutting a trace from Ledo to the Pangsau Pass, one of the highest points on the road. It touches an altitude of over 5,000 feet.

Col. Green's office moved right along with the Engineers and every day it was cluttered with officers and GIs seeking advice, checking this and that and going over maps and plans. The Colonel was popular with the GIs for a reason separate from his road construction talents. In 1924-25 he played football with the famous Red Grange at the University of Illinois.

|

His men had constructed one of the longest ponton bridges in military history. It spans the Irrawaddy River. They had built a wooden causeway two miles long over jungle swamps and estimates of the lumber used in this structure show that more than a million board feet were used. This is another of their accomplishments during which they had lived through miserable days of sizzling heat and sickening wetness.

When they came, Burma was a strange country to them. They worked with strange people. There were 12 to 15 thousand Chinese laboring on the Ledo Road and even they were first looked upon curiously by these blustering engineers. As their work continued, they came in contact with a still stranger lot, even to headhunters whose homes proudly exhibited some unfortunate skulls.

These were the natives of the Naga Hills. The GIs traded with them, bought things for them and from them and used enough plain shirt-sleeve diplomacy to win their confidence. Soon they were "bossing" them on jobs along the Ledo Road.

The Engineers - Road Gang they call themselves - began to live an every-day life with the Shans and the Kachins, the latter becoming known as the most pro-Allied group of people in this war. They're so completely pro-Allied because they are so bitterly anti-Japanese. The Kachins working behind Japanese lines tossed a wrench into dozens of enemy maneuvers that might have delayed completion of the road had they been successful.

The Nepalese were another tribe the GIs associated with. They came from Nepal, a small state bordering on northern India, and before being enlisted for work on the Ledo Road, they hadn't heard of wages such as were being paid the laborers. It wasn't easy to induce the Nepalese to remain on the job after their six-month contract expired. They worked just long enough to get "rich" and then retire to a comparatively luxurious life.

THE ROAD GANG will get their most pleasant recollections from the Burmese along the Taping River where the GIs lived in native bashas, small thatched huts, and tents. Each day their skimpy homes were enlivened by fresh flowers that the natives placed in the huts and tents. Here, the natives didn't at all seem to mind what the GIs thought was the short end of a bargain. The ponton bridge engineers had for a pet a tame otter that Pvt. Wilfred Smith of Danford, Me., bought from these natives for two boxes of matches. Trading on this basis was a regular pastime and GIs filled mailbags to the tops with souvenirs shipped home as quick as they were bought.

What the little things in life can amount to, the Road Gang is well prepared to evaluate. They had not seen a white woman in more than a year. The first Stateside legs they stared at belonged to a contingent of nurses who came to Shingbwiyang in the fall of 1943. These men became the most gentle of all movie critics because in the jungle and wet valleys flickers of any sort were scarce. Ice cream got to rate high as a pleasure and as a diversion.

Whenever they could, GIs hunted wild game. Sambar deer and pheasants are plentiful along the road. But even in their hunting pleasure the Engineers found that things didn't go altogether so smoothly. Pfc. Boyd H. Bard of Fort Loudon, Pa., almost cashed in his chips one night while hunting bear.

He spotted one and fired several times, but only wounded the animal. It charged straight for him. It kept coming. Flustered, Bard poured in shot after shot but missed each time until the last cartridge clicked into the carbines barrel. Bard dropped the bear with that last round. But he still gets the shakes every time he thinks of the distance there was between the dead bear and himself.

The ponton bridge engineers think they ought to adopt "One More River to Cross" as a theme song. On the Ledo Road they bridged 10 of them: the Taping, Tirap, Namyung, Namyang, Tarung, Tawang, Tonai, Mogaung, Irrawaddy and the Shweli. These were just the bigger jobs but in addition they spanned 155 smaller streams.

Men who figure out things by putting them end to end and then telling you where they'd reach have calculated that the Engineers moved 14 million cubic yards of dirt. That's the Ledo Road in one pile.

|

|