One day in February of 1945 when the 1st Sgt. asked for volunteers to drive the Ledo-Burma Road into China, I was one to submit my name. Even before I had entered the Army I had heard of the Burma Road - heard of it as being the most dangerous route in the world over the roughest terrain imaginable. And when I was assigned to duty in Assam, India, in 1943, I realized I was close to the road and hoped one day to drive it. This was my opportunity and I jumped at the chance.

February and March passed by and no word came as to when I was to leave. I had almost forgotten that I had ever volunteered, but on the 18th of April, orders came down from Headquarters for me to report on the 22nd. In things like this the Army moves slowly and it was the 28th of April before the convoy was finally organized and ready to move out on the road.

At 10:30 that morning we were underway... The first stretch of the Ledo Road from Ledo, Assam to Shingbwiyang, Burma offered the most tedious bit of driving I had seen up to that time. The road was in comparatively good shape, but the steep grades and curves made driving the job that it was. In one particular spot we were on an upward climb for seven long miles until we finally reached the crest of the hill, 6800 feet above sea level.

As I drove along the outer edge of the road, I glanced down over the cliff to see what must have been a 2000 foot drop into the valley below. We were then above the clouds and they stretched out to the side of me like great puffs of whipped cream. It was a beautiful sight, but it made me a bit uneasy when I realized that no more than a slip of the wrist could cast me down through space like a rocket.

But there was nothing hard about this upgrade driving. With the truck in low gear and traveling about five miles an hour I would sit back and relax with one eye on the scenery and the other on the road.

It was the downgrade "flights" that made us sweat blood and I was no exception. By selecting a reasonable gear a man could keep his truck at a speed that was safe enough or slow enough to enable him to make those hairpin turns and descents, but a mechanical failure in the truck could put it entirely out of control. Before we left we received explicit instructions that if such a thing should happen we were to get out on the running board and jump while we still had the chance. A truck is easier to replace than a man. Luckily no accidents occurred on the first lap, but the strain on the trucks was tremendous.

It was after dark on that first night when we pulled into a convoy camp for a little rest. We were as weary as a man can be - hungry, thirsty, dirty and tired. But after we had bathed in a cool mountain stream, we began to feel better.

We ate "10 to 1" rations that night as we did for almost every evening meal of the trip. This is the best emergency rations that the Army issues. It is designed to feed ten men for one day and if properly prepared, it offers a meal fit for a king. To mention a few items - there is canned uncooked bacon, pre-mixed cereal, English style stew, etc.

Before we left on the trip we were issued jungle hammocks because no shelter other than this would be provided on the road. The jungle hammock is a unique little affair. It is a tent, mosquito net and bed all in one. We would string the hammocks from one truck to another and they provided a comfortable night's rest.

It was a smooth, level road with an occasional hill here and there, but we weren't out to make time. The convoy traveled between 20 and 25 miles an hour and we took frequent breaks for a smoke and relaxation. Harder days were a head of us so we took advantage of the easier ones. We arrived in camp late that afternoon, but we were early enough for a swim in a deep, cool stream. This was my first swim since the summer before I came in the Army, but when I hit the water it was as if I had never been away.

|

The next day's drive put us further into Burma. We were traveling in open country then and some good time could be made on the fine road that stretched before us. In spots where there had been no recent rain the road was like a river of dust. The convoy was opened up in these dusty stretches until there was a mile or more between trucks. It seemed as though I was alone then and with the trees forming a canopy over the road.

After miles of travel on the third day out, we crossed the Mogaung River and a few miles past that we hit the Irrawaddy. We crossed the Irrawaddy River on a pontoon bridge that the American Engineers had constructed shortly after the capture of Myitkyina, which lies 15 miles to the north along the Irrawaddy. The river, although it appeared small to me, is a half mile wide at this point. It flows with a slow current and the water is deep and clear.

The Ledo Road did not run through Myitkyina and for a while I thought I was going to miss seeing the spot where Merrill's Marauders made their gallant stand. But the next day we drove into Myitkyina from our camp to unload what supplies we had and to pick up more destined for China. The fighting was over a long time ago there, and the wreckage was pretty well cleaned up. The only remaining signs of battle were a few bullet-riddled, mortar blasted buildings and freight cars. We did no actual traveling on the road that fourth day, so spent most of our spare time swimming in the Irrawaddy.

The fifth day found us heading for Bhamo. The Ledo Road was not what it had been on previous days, but we plugged along and around 3:30 that afternoon, rolled into Bhamo. Here again we met the Irrawaddy, and it was such a warm day that its cool water was like manna from heaven. Bhamo showed signs of the fighting that took place there. Bomb craters and damaged equipment were to be seen everywhere.

We had an early start out of Bhamo the next morning and it's a good thing we did, for the terrain we encountered was rough and mountainous, and driving was slowed down. Here I must remark on the beauty of one place we passed that day. The road was cut through the center of the hill and the banks to either side were of a rich red clay. It wasn't this common salmon red that is seen so often, but was a deep color - more of an auburn - and a beautiful shade for a woman's hair.

The road continued on, snaking its way through the hills and up, down and around the mountains. Hills make beautiful scenery, but if I ever hoped to see some level land, I hoped for it then, In time I finally had my wish. The road straightened out and the truck, I believe was as much relieved as I. We both had had a hard pull that first 60 miles of the day's run and it seemed as though we coasted the rest of the way to camp.

If you can imagine what a golf course would look like on a fifty square mile scale, you can picture the scenery around the convoy camp where we stopped on that sixth night. The hills were high and rolling, and patches of bright, red clay loomed up through the short grass, striking a beautiful contrast.

The next morning two miles out of camp, the Ledo Road linked up with the Burma Road and a few miles past that we crossed the border into China. Both Chinese and American MPs guarded the gate and the Chinese flag like our own was at half-mast. I thought this was a fine tribute to FDR.

This was my first day in China and it struck me as being a very beautiful country with its high grass, covered mountains and its quaint, little people. We made one stop in a small Chinese village that had been pretty well blasted out by the Japs. Its people were only poor peasants and it seemed as if all their clothes, including their hats and the little sandals they wore, were made of the same material - blue denim.

The little kids with their slant eyes are really cute. Their skin is the color of rich cream, and their hair so soft and fine. I really took one little fellow to heart. He was only about the size of a minute, and even though I couldn't understand his language, he made it plain that he wanted to sit in the cab of the truck. I hoisted him up in the driver's seat; he put his little hands on the wheel and looked down at me all smiles and said, "Ding How." There are very few words in Chinese that I know, but these two are the equivalent of our "Okay."

We were soon on our way again, and as I was driving along I saw a woman who appeared to be in a pitiful condition. She was carrying two baskets up a hill and it looked as though her feet had been chopped off at the instep. I felt sorry for her, but she seemed to be managing all right. A few miles down the road I saw another with her feet in the same condition, and it dawned on me that this was the result of the ancient Chinese custom of binding the feet of a baby girl. The Chinese might think this is beauty; I can't see it myself.

|

We camped that seventh night in the mountains and I don't know when I ever had a colder night's sleep. I had four blankets over me but the wind howled and cut through me like a knife. I was happy to see the dawn break and the sun come up with all its warmth.

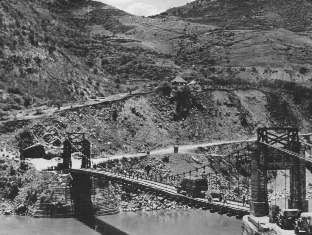

We were traveling in the mountains again on the eighth day and could average no more than 12 miles an hour. After about two hours of driving, we crossed the Salween River on a one-lane suspension bridge that I'm sure has seen better days. The Salween at this point is a gorge between two mountains, and after crossing the river, we scaled the mountains to the west and when we reached its peaked we stopped to enjoy the view. The bridge we had crossed lay down below 4,000 feet and it appeared as only a thread across the river. It was a beautiful view and here was one of the thousand times on the trip that I wished Dad and his camera were with me. The Ledo-Burma Road would be a photographer's paradise. I have never seen anything to equal the scenery that I saw on that trip and will probably never see the likes of it again.

We pounded the Burma Road again all the next day, along toward nightfall coasted into the Paoshan Valley. There was a GI camp here at Paoshan and the hot meal and shower that were waiting for us was a welcomed treat.

When we started out again the next morning, we passed through the town of Paoshan, which must be a thousand years old if it's a day. It's a stone city, encircled by a thirty-foot stone wall. It looks fallen down and beaten by time, and I had the feeling as I was passing through the great arch into the city that I was intruding on something out of the middle ages.

It was late that night when we pitched camp. We had battled the Burma Road for a hundred and thirty-eight miles that day and it had taken us fifteen hours of hard driving to do it.

That night Dick Murphy, Jerry Goodrick and I had one of our evening feasts. We had several of these evening meals together and here we spent in each other's company the most enjoyable hours of the trip. They were both fine fellows, full of laughs and they, like myself, had a variety of stories to add to the conversation. Each time we had the chance we would buy a dozen or more eggs from the Chinese and these fried with the bacon from the "10 to 1" ration, along with a hot cup of coffee, gave us a meal that I considered the best. On several occassions we bought a quart of fruit wine - not very strong, but it was wet and made an enjoyable drink, and we would sit and talk until the fire we had made died away.

The next two days of driving were rather uneventful, and I can remember nothing of them at all, except of course, that they brought us up to 114 miles of our destination - Kunming, China.

We didn't move out again the next morning as we had expected. All the trucks needed attention even though it was mostly minor items. By noon everything was in shape again, but since it was too late in the day to make Kunming before dark, we decided to lay over until morning.

We started out right after dawn on that 13th morning and I was happy to know that this was to be the last lap of the trip. The Ledo-Burma Road had offered many exciting moments, but the novelty of it all had worn off and I was anxious to reach our destination. Each mile seemed to be longer than the one before it.

At 3:30 that afternoon, we reached the crest of what I knew must be the last mountain we had to climb, and there in the valley to the other side, like a picture from an old story book, lay Kunming.

A few minutes later we rolled through a great stone arch, down a narrow, cobblestone street and into the heart of the city. Chinese soldiers and civilians blocked our way, swarmed over the trucks and greeted us with enthusiastic shouts of "Ding How!" This was it; this was the end of the Ledo-Burma Road.

I must pass out a few orchids: to the Ledo Road and to the men who built it, and to the GMC 6x6 truck I drove

over the road for 1,156 miles without a mechanical failure. It pulled along over the roughest terrain in the world

with an untiring effort, climbing steep grades with ease and putting out speed when called upon to do so.

An original story from Ex-CBI Roundup, November 1988

Adapted for the Internet by Carl W. Weidenburner

TOP OF PAGE

PRINT THIS PAGE

CLOSE THIS WINDOW