|

The road engineers reached several important goals as 1944 ended and 1945 began. In early December they completed a 1,150-foot pontoon bridge across the Irrawaddy south of Myitkyina to Waingmaw, one of several crossings of that stream. Built by Capt. Donald E. Tousley's 75th Engineers, this 25-ton structure of aluminum and wood was the Corps of Engineers third longest pontoon bridge, the longer ones being over the Rhine in World War I and the James during the Civil War.

The graded portion of the road reached this point the same month, and surveying and clearing got 15 miles farther to the southeast the first week in January.

A major maintenance job back in the Hukawng Valley was finished during this time. The engineers dismantled the long causeway over the Magwitang swamps built during the height of the 1944 monsoon and replaced it with a big dirt fill as high as 18 feet to get above the floods of the future. Two hundred thousand yards of dirt and 10,000 yards of gravel replaced thousands of feet of pilings and lumber.

But the biggest goal of all to the road gang was reached as 1944 waned. Many of the oldest hands, high rankers and low, were rotated home to Uncle Sugar.

With the exception of a railroad trestle at Mandalay, no man had ever tamed the Irrawaddy River with a bridge. The Tousley pontoon across the stream to Waingmaw was the first span on which an automobile could roll across. One was not enough for the engineers and the need, however. They had two more in mind, as well as a couple of ferries. The high Patkai Range and the flooded Hukawng and Mogaung Valleys, had been the road troop's first two big obstacles, and the Irrawaddy was their third when it came to the question of a permanent bridge.

Planning for it had been going on for a long time, as the Office of the Chief Engineer back in Washington knew they had better think about crossing the river before they got to it.

In the first place, the British and American estimates of the river's past and possible future behavior were, to put it mildly, a jungle mile apart. Washington said the low-water-mark would be three feet, the British said 40. Depth at high water, according to Uncle Sugar's Pentagon engineers, would be 20 to 40 feet, While British Lt. Col. W.E.C. Roper in a report on the subject predicted 80.

They were closer together on the width and velocity of the stream. The Chief Engineer's Office in Washington estimated the Irrawaddy would be 1,650 feet wide at maximum flood and would flow at eight feet a second. Colonel Roper, as a liaison officer to General Pick, forecast 1,800 feet across and 10 feet a second maximum velocity.

Later conferences turned up still different data: low water depth 25 feet, high 66 feet, maximum width 1,800 feet, and maximum velocity 12 feet a second.

New Delhi and Washington favored a steel trestle bridge, while General Pick and Col. Thomas F. Farrell, head of the construction service, leaned toward a pontoon structure. As it turned out, part of it was a floating bridge and part fixed.

There were 10 metal barges in Calcutta which the engineers thought could be used to support the floating structure - huge flat-bottomed boats, 104 by 29 by 8 feet in dimension, weighing more than 100 tones each. These barges, sent to CBI for a barge line on the Brahmaputra River envisioned by the Quebec Conference, had been gathering

|

The barges, after being tested on the Houghly River as pontoons, were hauled down the road to the bridge site, and the 1007th Engineer Special Service Battalion was ordered from Calcutta to assemble the bridge.

Apparently the bridge planners gave no thought to the fact that the waters of the Irrawaddy rose even before the monsoon from the melting snow of the Himalayas. The engineers got this information from the local population. When the engineers established this to their satisfaction, they knew they wouldn't have time to wait for some of the material and parts ordered from the States. Some of it couldn't be found or made in CBI, so they promptly replanned and redrafted the span to conform with what they had.

The barges to be used for pontoons, each bigger than the LCTs used to carry tanks in Pacific invasions, arrived shortly after New Year's Day 1945, and the 1007th Engineers began assembling the bridge before mid-month. Seventy-eight days later, at the end of March, they opened the 1,627-foot structure, a two-lane crossing 23 feet wide. The floating section of the span, 853 feet, rested on seven of the 10 big barges, and on each end was a 228-foot transition structure. These were connected to a 318-foot wooden trestle on the east bank and the road on the west.

In addition to the 1,150-foot pontoon bridge built by Captain Tousley's 75th Engineers at Waingmaw, Capt. John H. Monger's 71st Engineers built another, a 1,300-foot floater, at the site of the permanent bridge. There were also ferries at both places, a total of five ways to cross the Irrawaddy along the Ledo Road below Myitkyina.

Now that Pick's Pack, as the engineers were sometimes called, were over the Irrawaddy, which way would the Ledo Road take the remainder of the way to China? There were three choices. The first was from Myitkyina to Paoshan or Lungling by way of Tengchung, sometimes called the Tengchung Cutoff or the Marco Polo Trail. The second was from Myitkyina to Tengchung via Bhamo up the Taping River Valley, referred to variously as the Taping River Route or the Gold and Silver Road. The third potential route was from Myitkyina to Wanting through Bhamo and Mong Yu, which took advantage of the post road running north from Bhamo to Waingmaw and Myitkyina. The route to Wanting won.

With the Irrawaddy tamed and the exact route determined the remainder of the way to China, the 209th and 236th Combat Engineers worked to open the last miles as the sound of battle disappeared into the hills south of Bhamo. Wanting, across the Burma border in China, was taken from the Japs in late January.

Since it looked as if the route to China would be open before February, except for straggling pockets of resistance, General Pick began to organize a ceremonial "First Convoy" to China at Ledo in early January, a caravan of 113 vehicles, including jeeps, weapons carriers, ambulances, and trucks, some of them pulling artillery. He planned to use drivers from the engineer outfits that had built the road. The term "first convoy" signified the first overland convoy to break the blockade of the Japanese armies by successfully delivering war material to Kunming.

The sun was high and the sky clear at Ledo the morning of January 12, 1945, and that GI hot spot was teeming with its usual activity when the traffic to Mile Point 0 was stopped by military police. Very few who halted their vehicles knew what was going on as Pick's First Convoy to China was getting ready to move out. A military ceremony was planned, strictly a family affair, a move-out to be recorded by soldier correspondents and GI cameramen. The only spectators were soldiers who just happened to be there. Correspondents and cameramen of the press, radio, and newsreels were waiting for the convoy at Myitkyina, 262 miles away.

By early afternoon the waiting convoy flanked the road below Mile Point 0 like an endless ribbon of rubber and olive drab. When the three-starred jeep of Lt. Gen. Daniel I. Sultan, the India-Burma commander, sped toward the head of the convoy, the drivers, standing by their vehicles, snapped salutes. The Sultan jeep rolled to a stop in front of the lead truck. General Pick, waiting with the rest, welcomed Sultan with a salute and handshake.

"Sir," he said, "the Ledo Road lifeline to China is open. I have the first convoy formed and ready. I would like you permission to take it through to China."

"Congratulations, General Pick," Sultan replied. "You have done a splendid job. I am confident this is the first of many convoys to go along this road to our Chinese allies."

"Line 'em up, Mullet," Pick called out to Col. DeWitt T. Mullet, the convoy commander. Mullet gave the signal, and the caravan moved into the Naga Hills.

Two military policemen with white gloves and helmet liners raced ahead on motorcycles, the lead truck, looking like a streamlined covered wagon, behind them. Big signs on both sides, read "First Convoy over the Ledo Road. Pick's Pike - Lifeline from India to China." The top was "fancily" painted, and on the cab in a zipper-closed cover, a revolving antiaircraft gun pointed toward the sky.

A seemingly endless parade of brand new vehicles followed, the cargo types loaded with supplies, all of it to become Chinese property when it reached Kunming, nearly 1,100 miles away.

American and Chinese soldiers rode in each rig, both wearing their standard uniforms. The Americans drove, leaving the Chinese free to relax and acknowledge whatever cheers the road might have to offer. It would be the privilege of the Chinese to drive the convoy into Kunming, where joyful shouts would more likely be forthcoming.

To Staff Sgt. Edgar Laytha, a field correspondent of the CBI Roundup, the first 30 miles of the road were like the outskirts of an American metropolis - plenty of traffic and gas stations. A multitude of toiling Americans and military units flanked the road - trucking outfits, maintenance units, hospitals, and warehouses. This soon vanished and Laytha found himself on a thin thread of road through a cloth of dark jungle.

Laytha's reaction to the road was excitement. The flag-decorated convoy, with MPs racing from one end of it to the other, brought reality to a three-year-old dream. It was the culmination of two years of toil against monsoons and mud, ruts and rocks. Observers along the road responded, each in his own way. Some waved, some shouted, and many smiled. Many GIs called "ding-hao" to the Chinese, and a few snapped to attention and saluted the fluttering flags.

American black engineers, some to be selected as convoy drivers at Myitkyina, grinned as they toiled at road maintenance. Indian Pioneer workers and Chinese troops cheered. Colorful Nagas and round-eyed Kachins, working barehanded and barefooted, seemed to wonder what the excitement was all about, The road was truly international.

Climbing mountainous loops and curves after leaving Hell Gate, the convoy snaked up to Pangsau Pass, where less than two years before, the first American bulldozer had pushed across the Burma border. The convoy halted on the edge of the deep abyss, and the drivers gazed northward to the white peaks of the Himalayas. The high mountains climbed like shining stairsteps into the sky, beneath them a huge range of lesser alpine heights. Farther down, hills swam in an indigo haze, dropping into green depths of jungle. Gazing back of the convoy into that green depth, Sergeant Laytha saw some of the vehicles several thousand feet below still winding up toward the pass.

The caravan moved on like a long mechanical snake, descending around the bold horseshoes and oxbows of the Patkais' eastern side. As the sun set, the air grew crisp and cold, and flaming buckets of oil lit up danger points, painting the cliffs with flickering light and shadow. These were some of the same buckets General Pick had ordered when inadequate electrical illumination had made a round-the-clock duty schedule impossible. Looking back from the truck in which he was riding, Laytha thought he saw village lights after darkness fell, but there were no villages. They were the headlights of some of the vehicles in the trailing half of the convoy.

|

Some of the drivers had never been so far on the road, others remembered the toil, the steaming humidity, and the little respite they got from both in water-logged tents. They remembered that most of the road was wrenched inch by inch from the Japs. Only 42 miles were constructed through friendly terrain. Laytha thought of the departed General Stilwell, recalled to Uncle Sugar less than three months before. "Pity he's not here for this," he thought.

The convoy reached the upper Hukawng Valley, bivouacking at Shingbwiyang. The drivers and passengers used the jungle hammocks they had brought along, and next morning they ate breakfast served by American black troops in a big 24-hour transit mess.

From Shing, the more or less flat highway coursed widely through a pretty forest which turned into a swamp in the monsoon. As they wheeled along, the drivers glimpsed burned-out tanks beside the road and in the river beds, mechanical casualties of the jungle battles to clear the trace. On they rolled past service stations, past Walawbum and Tinghawk Sakan, through Jambu Bum Pass, into Shadazup and Warazup. They stopped at Warazup for their second night on the road.

Next morning heavy fog blanketed the Mogaung Valley and the road, muddying the heavy layers of dust caked on headlamps and windshields. At mid-morning the fog faded and the sun came out, with it many liaison planes from which Signal Corps cameramen photographed the cavalcade.

The convoy reached General Pick's triangle, sometimes called the Myitkyina Fork, about 10 miles from Myitkyina, where one fork of the road ran on to Bhamo and the other turned left to Myitkyina. There, 40-odd war correspondents and photographers - American, Chinese, English, Australian, and Indian - blocked the convoy. Til Durdin, Teddy White, Al Ravenholt, Jim Brown, George Johnson, and soldier correspondents asked questions and took notes. Three radio teams recorded and Signal Corps photographers, War Department cameramen, and British and Chinese newsreel men took motion pictures. Representatives of the War and State Departments took official notice. Three GI artists, Technical Sgt. Milford Zornes and Corporals Theodore Sally and Sydney Kotler went about sketching the surrounding scenes. This impressive array of mixed history and publicity was to turn sour before the convoy left Myitkyina.

For the moment, GI and Chinese drivers dutifully smiled into the cameras. Pick, with his famous pilgrim stick, just as dutifully walke3d to a little hill in the middle of the road junction and pointed toward China. The convoy then rolled into Myitkyina and moved into a special bivouac area in the center of town. The drivers washed-up, unlimbered their legs on the way to chow, and went to see Hedy Lamar at a GI movie.

The convoy personnel knew they would have to sweat it out in Myitkyina for a while, possibly two weeks, waiting for Namhkam and Wanting to fall. The Japs would have to be cleared from the road farther south.

There were dinners and Special Service shows while everybody waited for news from the front. The foreign correspondents, impatient to be on the way, began to ask when the convoy was going to roll. They repeated the question daily, ad infinitum. lt. Col. Don C. Thompson, General Sultan's public relations wallah, a Harvard man, became so harassed at the correspondent's heckling that he issued a press release in the style of Gertrude Stine.

"What are mountains?" he wrote, "Mountains. What is mud? Mud. A convoy is a convoy is a pain in the neck." He wasn't half as harassed as he would be before he left Myitkyina. Trouble for him and Generals Sultan and Pick was brewing along the Marco Polo Trail or Tengchung Cutoff, east of Myitkyina.

The previous August and September, engineers, members of the Mars Task Force and other troops went on a nine day expedition to determine the feasibility of this alternative route to China in case the Japs were not removed from the Ledo and Burma Roads south of Myitkyina.

Col. Robert F. Seedlock, in charge of the Burma Road Engineers out of Kunming, and C.C. Kung, director of the Chinese Yunnan-Burma Highway Engineering Administration, had been given the responsibility of making this track of antiquity into a passable dirt and one-track motor road.

The official "first" convoy, waiting in Myitkyina for fighting to clear its route to the south had been billed as the "first overland convoy to break the blockade of Jap armies" to China. While it cooled its tires, the Seedloack-Kung forces were at work to achieve that laudable distinction. According to stories I heard, Cutoff crews worked 48 hours straight to complete the Cutoff to the China border so some of their vehicles could head for Kunming ahead of the Sultan-Pick extravaganza. heavy bets were placed, according to the stories, that Cutoff vehicles would get to Kunming ahead of Pick's.

On the morning of January 20, 1945, as Colonel Thompson parried correspondents' questions in Myitkyina, another American convoy, a wrecker and two battered 6x6's, rolled over the border into China and headed for Kunming, where they arrived two days later. As the convoy moved out in the charge of Lt. Hugh A. Pock of Stillwater, Oklahoma, it was witnessed mostly by Colonel Seedlock's Burma Road Engineers and Director Kung's Chinese Cutoff workers. One engineer a long time after said there was a shout of "We'll take Pock over Pick" as the vehicles reached China soil. The Seedlock-Kung caravan of three vehicles had a start on Pick's 113 of at least one day and was 200 to 300 miles out in front.

When the foreign correspondents with Pick's convoy got wind of this, they acted like disturbed hornets. They buzzed about the ears of Colonel Thompson, complaining about the "wrong convoy," not the "first," but a "poor second."

Pro-Pick arguments were advanced that Pock's three vehicle train had not traveled over the Ledo Road, but only touched it at Myitkyina, while Pick's, with 110 more, was traveling not only the Ledo Road's length but also the Burma Road from Wanting to Kunming.

Generals Sultan and Pick must have considered silence the best policy, as they clamped the lid on the public relations can. Colonel Thompson and his word wallahs clammed up, and poor Colonel Seedlock couldn't even get an Army photographer to take a picture of his blockade busters.

The Chinese were free to talk, however, and talk they did. In no time at all, Lt. Gen. Albert C. Wedemeyer, the China Theater boss, Chiang Kai-shek, Lord Mountbatten, and even Winston Churchill were polishing their best phrases in honor of the Seedlock-Kung-Pock accomplishment.

Heartened by India-Burma's silence and disheartened no doubt by China's failure to keep it, General Pick and his convoy left Myitkyina January 23, a foggy Tuesday morning, after a wait of eight days. The Japs were off the track to the south. Or, so they thought.

A Navy jeep beat both Pick and Pock as the first vehicle to get to Kunming, and it traveled the full length of the road from Ledo. While the brass was busy with its big show of launching the "first" convoy, Navy Lt. Conrad A. Bradshaw and sailor William F. White chugged past those proceedings and headed down the jungle highway. In so doing, Bradshaw was AWOL from his duty as second in command of the Sino-American Co-operative Organization (SACO) air cargo transshipment station at Jorhat. He wanted SACO to be the first to roll the nearly 1,100 miles over the new motor highway and the Burma Road to Kunming.

Bradshaw and White made it about four days ahead of the big Army convoy. They were hungry, dusty, and weary

when they go there, but they thought it was worth it for SACO to have the distinction of getting the first vehicle

and men over the first modern road to link China, Burma and India. SACO must have agreed. It disciplined Bradshaw

for unofficial absence by having him report fully details of his trip and his opinion about the use of the road

for Navy convoys.

|

The Pick convoy, the day it left Myitkyina, moved into Bhamo after dark for its first complete field bivouac, the drivers and their passengers slinging their jungle hammocks between two rows of vehicles the night's rest. The Americans settled down in front of their gasoline stoves to warm up their K-rations while the Chinese ate chow from a regular field kitchen. The convoy's defense unit, Ramgarh trained Chinese soldiers, posted guards and one by one, most of the men crept into their sacks. Some, however, stayed up late. American and English-speaking Chinese officers gathered around the communications car and listened to the news of Joe Stalin's march on Berlin.

CBI Roundup correspondent Edgar Laytha lay in his hammock listening to conversations of the night owls in the soft silence. Laytha heard Staff Sgt. Robert B. Goodman, driver of the lead truck and first sergeant of the convoy personnel, talking about driving the first convoy vehicle into China. He seemed proud. "It's quite an honor, I guess," Laytha heard him say.

Laytha overheard two of the black drivers they picked up at Myitkyina discussing a soldier who offered them a thousand rupees if they could get him duty as a convoy driver. Cpl. Summer Grant, a black soldier driving Laytha's jeep, told Laytha before he went to sleep that he was going to write his old farmer father back in Georgia a diary of the trip if censorship permitted. Talk about great things and small finally faded, and Laytha, with no one else to listen to, dropped off to sleep himself.

Next morning the convoy headed for Namhkam, about 40 miles southeast, which the Japs had left only a week before. As the caravan rolled in, Namhkam looked much like Myitkyina and Bhamo after the Nips had cleared out. The elaborate monastery of the Golden Eye in the center of his little jungle town was a heap of ruins.

As the convoy rolled through this town Marco Polo had visited on his way to China, lonesome GIs waved to the drivers from the porches of empty houses. Sitting like little rajahs, they were doing nothing except reading old American magazines. The caravan rolled through to the other end of the town and bivouacked.

The wreckage of Namhkam retained a pathetic splendor, curiously inviting to the interested convoy personnel. With their canopies and supporting pillars stripped away, monumental gold-plated idols towered over the sea of rubble. A few still carried attractive marble heads on golden shoulders, but many had lost theirs, now down deep in the debris 15 feet below. The smaller gilded figures of minor deities, also beheaded and armless, were heaped around the large jewel-studded thrones like a faithful bodyguard fallen to the last man. The convoy men crawled over the fallen walls, climbed to the shining shrines and snapped one another's pictures in the lap of Buddha.

The convoy hadn't been settled in bivouac long when thunderbolt news struck. Around the village of Mong Yu, 25 to 30 miles northeast, heavy Japanese artillery was shelling the road from hill emplacements. When the Japs retreated toward Lashio earlier they had left these batteries in hiding, their mission obviously to wait for coming convoys.

Meanwhile, back of the convoy, another one, longer and more complex, formed on the road because of what appeared to be enemy movement.

Robert E. Burke, an American soldier responsible for field telephone equipment near the encampment of the Chinese 38th Division, awoke early in the morning, stirred from slumber by the roar of 6x6 trucks on a trail about a mile off the Ledo Road. Burke pulled on his pants and headed bare-footed down the trail. The road was busy as a beehive, with loaded trucks leaving and other being loaded with equipment and baggage. Obviously, something was wrong. Burke broke into a run.

Arriving breathless at the division communications office, he demanded to know what was going on. A sergeant told him that Kachin scouts had confirmed that a Jap force was moving in over the trail on which they were camped. During the night, he said, a decision had been reached to evacuate all Chinese and American encampments along that stretch of the Ledo Road; they were to seek safety over the border in China where the Chinese Y-Force was located.

The thought that tents could be struck during the night for a pullout at dawn without a word of warning to him angered Burke. The only preparation he had made was to pull on his pants.

Burke told Sergeant Ryles of the communications center that he needed truck space for his electronic consoles weighing 800 pounds each and his generators, batteries, and drums of gasoline. Ryles expressed his regret. The last trucks of Headquarters Company of the Chinese 38th Division, fully loaded, were just pulling out.

Burke hurried back and found four or five linemen serving with him. They loaded his two Carrier consoles on his three-quarter-ton truck, a big effort for six men. They found enough space for four storage batteries, tool kits, some cable and an unfolded cot. This being the most they could accomplish. Burke and a sergeant drove off with the load, leaving everything else behind.

On reaching the Ledo Road, they found it filled with trucks bumper to bumper, each piled high with men and equipment. They were waiting for the signal to move to China. After nudging into line with their small truck, Burke started walking up and down the convoy looking for someone with enough room in his heart and vehicle to drive back and save his generators. Burke was slogging back through the dust to his truck without success when he spotted an empty weapons carrier slowly threading its way in the opposite direction. The driver was on his way to pick up his Chinese telephone cable laying crew to join the general retreat.

Burke, accomplished in speed and persuasion, talked the driver into picking up his two generators first, then "packing his Chinese around them." Back at the site of the power equipment, Burke and the driver managed to wrestle the generators into the weapons carrier.

Retracing the route down the trail, they turned onto another and reached a beautiful two-story Burmese house where the cable-laying crew was quartered. Five Chinese were rushing in and out of doors piling up a mountain of baggage. When the Chinese lieutenant saw his transportation was only one weapons carrier already loaded with two motor generators, he screamed with rage and frustration. After he calmed down, the Chinese loaded as much of their gear as possible and climbed aboard. Off went the truck with all eight men and the heavy load toward the Ledo Road.

Back on it, they saw motionless vehicles packed for a quarter mile in each direction, trees blocking the view of many more. Nothing stirred in the warm winter sun except flies and bugs. Burke found his truck and fellow soldier, Sergeant Baker, and they joined others in eating K-rations in the shade of the vehicles.

After eating, Burke took a field telephone, and gaining access to a plug coupling on the cable, hung on crossed bamboo poles, raised Namhkam, where Pick's convoy was waiting. Burke found both the Namhkam and Bhamo exchanges had been waiting for a call from him. Neither Burke nor the exchanges had anything to report on the situation beyond what they already knew.

At 2 o'clock that afternoon, with retreat in progress for hours, an American captain from 38th Division headquarters phoned Bhamo and asked for a plane to scout the latest position of the Jap force. Half an hour later an L-5 observation plane landed, the captain climbed aboard and headed toward the Jap troops. Thirty minutes later the plane was back, left the captain and took off for Bhamo.

The day after Pick's convoy reached Namhkam, Brig. Gen. Robert M. Cannon, chief of staff of the Northern Combat Area Command, arrived and conferred with Brig. Gen. George W. Sliney, Pick, and Sun Li-jen, commander of the Chinese 38th Division.

|

The convoy was forced into a second wait along the road, this time for three days, while tanks routed the Jap artillery above Mong Yu. It was a wait while the last battle for clear access onto the Burma Road was fought.

Pick and his six-mile caravan of vehicles left Namhkam the morning of January 28. It wheeled through demolished villages and bowled along over rolling terrain which two days before had been aflame with battle. Pick led his vehicles into war-shattered Wanting, nestled in low, barren foothills, that afternoon, 16 days after leaving Ledo. As the drivers rolled onto Chinese soil, they saw soldiers of the Chinese Salween Expeditionary Force filing down into Burma, dressed in tattered blue uniforms and straw sandals. These Y-Force men were in a tired army, weary after a 10-month campaign across the wild terrain of the Salween River country.

Dingy Wanting blazed with color as the convoy stopped for ceremonies. Pick waved his ever-present stick at the cheering crowds come to greet him and the first train of vehicles for China. High officialdom met the convoy, Dr. T.V. Soon, China's foreign minister, General Wei Lu-huang, commander of the Chinese Salween force, General Sun Li-jen, the Chinese 38th Division commander, Maj. Gen. Francis W. Festing, commander of the British 36th Division, General Sultan, the India-Burma commander, and Maj. Gens. Claire L. Chennault and Howard C. Davidson, respective bosses of the 14th and 19th Air Forces.

Uncle Joe Stilwell, back in the States for three months, didn't forget those who made the Ledo Road possible. "I take off my hat," his message read, "to the men who fought for it and built it."

As Pick spoke to the crowd, he seemed tired and weary to Sergeant McDowell, the CBI Roundup correspondent who had come all the way in the convoy. After the ceremony, the convoy pushed on up the Burma Road from the first town in China soil to its first bivouac on Chinese ground. Kunming and more ceremonies on a grander scale, were 600 miles away.

For another week the convoy rolled through green valleys and climbed over the pink barren mountains of Yunnan in clear weather, the days warm and the nights crisp with frost. Through devastated Lungling and storm-swept Siakwan on Tali Lake, past bloody Sungshan, and across the deep gorges of the Salween and Mekong Rivers the winding mechanical snake crawled over ground Kublai Khan's archers had met the armored elephants of Burmese kings 700 years before.

The Burma Road was not an old road. Eight years before it did not exist. China, in 1937, fearful that the Japs would seize all her eastern and southern ports and railroads, as well as the Indo-China rail line from Haiphong to Kunming, decided to build the Burma Road from Kunming to the Burmese rail terminus of Lashio. The central government sent Yunnan Province the equivalent of less than two million dollars and advised this Siberia of China to get busy. In October of that year Kunming decreed that all people eight days journey on either side of the proposed route had stretches of road to build. These people, steeped in provincialism for countless generations, saw no need for the Burma Road; but at least 200,000 did as they were told, reporting with homemade adzes, bamboo scoops and baskets, and their own food to toil at Kunming's monthly wage of $1.45.

This Kunming-Lashio highway on which the Pick convoy was rolling, about 100 miles of it in Burma and 600 in China, had become known around the world as the Burma Road. Its 300-mile mid-section was the toughest, traversing the steep canyons of the Salween, Meking, Shengpi, and Yangpi Rivers. The flood crests of these deep, powerful streams had never been measured.

Over this ground and through these gorges during most of 1938 less than 30 men had surveyed, mostly with the naked eye and by the feel of the land. The fifth of a million men, women, and children workers who swarmed through these rugged mountains after them, eight feet of roadway for each human being, picked away at pebble, boulder, stone, and crag with their crude tools. They used explosives on only the most stubborn rock, black powder and primitive fuses. Dynamite was either scarce or precious.

The Chinese completed the Yunnan-Burma Road at the end of 1938 with 402 bridges but not a single road guard. Trucks could crawl along it like ants at 15 miles an hour. Thirty thousand Chinese were assigned to maintain it. Many trucks had been wrecked on its sharp curves and steep grades.

Bandits, thieves, and provincial transit taxes, the latter paid in kind out of American goods going to China, took their toll from the tonnage reaching Kunming. Chinese drivers with not the faintest notion of maintenance simply drove their trucks till the oil and grease were gone and the vehicles collapsed like the deacon's wonderful one-horse shay.

They changed for the better before the Japs blocked the road. Under a system recommended by three American traffic and trucking experts, Daniel Arnstein, Marco Hillman, and Harold Davis, the road's monthly tonnage quadrupled in 1941 before Pearl Harbor, and the beautiful part about it, most of it got to Kunming.

The Burma Road on which Pick's convoy was rolling now had been somewhat improved since that time by America's Burma Road Engineers and China's Yunnan-Burma Highway Engineering Administration.

|

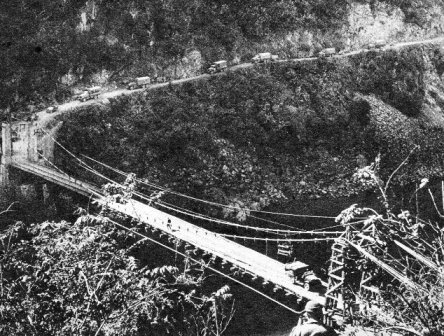

When the convoy reached the west bank of the Salween River gorge, the bridge far below looked like a foot plank across a brook. The drivers headed for the bridge, about 2,000 feet down around 35 staple-curve turns. It was the worst stretch of driving on the Burma Road, 20 miles of winding to crawl one mile down to the crossing. On the side of the road near next to the bluff a man felt reasonably safe, but on the outside the ride was scary, especially with a big truck bearing down on you from the opposite direction. Considering the number of trucks the drivers saw at the bottom of the chasms, a man was plain lucky to get down to the Salween and out again.

The importance of this stretch of the Burma Road to China in the late 1930s and early 1940s was pointed out clearly by Maj. John E. Ausland, who traveled up and down it extensively in 1941. Everything that entered China in those days went in over the Burma Road, and Ausland compared it to everything entering the United States going down into the Grand Canyon and up the other side.

The convoy, like all the vehicles that had ever rolled across the Burma Road's mid-section, moved 40 miles from the west rim of the Salween gorge to the east. The drivers steered down to the bridge, itself nearly 3,000 feet above sea level, and then climbed nearly as far above the river's level on the other side. Yet, when they gazed back, rim to rim, they had covered only a few miles across the narrow canyon.

The convoy's drivers had to keep alert, but those going along for the ride or other duties grew bored with inactivity at times. Sgt. Ralph Lowe, one of the CBI Roundup correspondents on the trip, amused himself by radioing droll communiqués without so much as a mention of a brass hat.

"In China, before every sharp curve," he wrote, "there is a sign with nothing but a bugle on it. You naturally ignore it, thinking it an advertisement for a local jive band, or maybe the Chinese just like buglers. After being hit a time or two by trucks coming in the opposite direction, you suddenly realize it's not a bugle, but a horn, and you're expected to blow yours."

After crossing the Salween River, Lowe filed the bulletin: "If, when rounding a curve down into the Salween gorge, you continue in a straight line, keep your composure and turn your jeep in for salvage at the nearest motor pool and yourself in at the nearest hospital. Neglect to bring your fire extinguisher because if your jeep catches fire you will have a chance to use your Yankee ingenuity to put it out. If, while driving your jeep, you get badly stuck in the mud, spin the wheels as fast as possible, thus miring yourself in deeper. This gives you a needed rest or a chance to catch up on your Army Institute correspondence course."

Lowe told the Roundup's editors about the most interesting man he met along the convoy's route, a fellow who had fought in the Salween offensive. He was going to officer's candidate school in Uncle Sugar. "During the height of the campaign when supplies were so short that everybody was hungry," Lowe wrote from Kunming, "this fellow rushed out onto a field where some planes were parked. 'Stop them! Stop them!' he yelled, 'These aircraft are eating up all the grass!' That's when they decided he was officer material," Lowe concluded.

Seven days after the ceremony at Wanting and 24 days after leaving Ledo, the convoy was approaching 7,000-foot-high Kunming, less than a decade before a medieval capital of 90,000 population, slightly influenced by the French from Indo-China, but now swarming with Chinese refugees and American soldiers. This city overlooking the jade-green water of Tien Lake, where poor families sold little girls into slavery for the equivalent of an American dollar, then had only 180 motor vehicles, but its streets were now thronged with rubber-shod wheels, even on the horse-drawn carts, which once had rattled and creaked unlubricated between the pepper trees on the main stem.

As the convoy drove in, days after the Tengchung Cutoff and Navy vehicles got there, the hardships of the road lined the faces of the convoy personnel, especially the drivers. They had come over the highest, longest mountain supply line in the world. The trip had left its mark on wind-burned faces, hands and lips, some cracked and bleeding from the cold. Their eyes were weary and blood-shot from long hours on the road. They had covered 1,079 miles without losing a single piece of equipment.

The convoy rolled up to Kunming's West Gate, where a ribbon was strung across the "finish line." Pick, in for more ceremony on the spot, met Lily Pons, the Franco-American singer, and her musician husband, Andre Kostelanetz, before the proceedings began.

|

Lung Yun, the governor of Yunnan Province, called "The Dragon Cloud" by the Chinese and the "one-eyed warlord" by General Chennault, together with Gen. J.L. Huang welcomed Pick and the convoy. "This is a happy occasion for China," Lung said. "The arrival of the convoy marks the opening of the great new highway just named the Stilwell Highway." He then quoted Chiang Kai-shek. "Let me name this road after General Joseph Stilwell, in memory of his distinctive contribution... in the building of this road."

Back in the States, Stilwell reacted. "I wonder," he said, "who put him up to that," then went on radio to praise the men "who fought for it and built it," just as the message did at Wanting.

"The Dragon Cloud," at the end of his remarks, handed "The old man with the stick" a silk banner containing Chinese characters. "Sheng li che lu," meaning "The Road to Victory."

Pick, responding, said: "One hundred yards away id the first convoy to penetrate the blockade of China in nearly three years. They said the job of building this road could not be done. But thousands of American engineers, Chinese engineers, and soldiers proved that it could. There stands the proof!" Pick motioned toward the convoy.

"You have arranged today's celebration in honor of the personnel of the convoy," he told the Chinese. "But the celebration should not honor these men. It should be in honor of the soldier's and engineers buried in the jungles of Assam and Burma. It should be in honor of the engineers who toiled and bled and fought to carve the road through jungles and swamps and across mountains to the Burma Road."

Lung cut the ribbon across the entrance to the West Gate and the convoy moved through into a massed polyglot crowd alive with color and motion. Eucalyptus trees lifted over dirty tile roofs, rickshaw bells tinkled, and the peanut whistles of the French locomotives on the narrow gauge railroad to Hanoi mingled in the morning air. The Chinese and Americans, black and white, behind the wheels of six miles of vehicles steered them carefully through the narrow lane of crowded humanity. The trucks, decorated with Chinese and American flags and festooned with red, white, and blue ribbons, eased slowly along the ancient cobbled streets. Chinese police in gray uniforms and Chinese soldiers with long rifles and fixed bayonets kept the crowds from completely barring the route.

It looked as if all of Kunming had turned out for the occasion. A solid wall of people lined the streets from the West Gate through town to the Services of Supply headquarters on the other side, where the convoy would become Chinese property.

The cool air of the high plateau was filled with colored banners and waving flags. "Welcome First Convoy Over Stilwell Road," some read in Chinese, and Vinegar Joe's picture was carried along as prominently as that of Chiang Kai-shek and President Roosevelt.

Chinese boy and girl scouts dressed in blue uniforms waved little banners, and school children proudly flapped vari-colored paper flags with Chinese inscriptions. American, British, Russian and Chinese flags fluttered on all sides. Firecrackers popped, and occasionally Roman candles skyrocketed burning balls above the procession. The drifting smoke of the burning powder made eyes sting.

Painted prostitutes, the "nice Chinese girls' many American soldiers had called to their attention on the streets of Kunming, mingled with merchants dressed in conservative American business suits. Coolies in rags crowded the curbs, and proud mothers and fathers held tiny children above the crowd to see the convoy. Chinese women in fashionable fur coats and western dresses mingled with women dressed in long, shapeless garments slit on the sides to their knees, and sometimes to their thighs.

People clung to balconies and leaned out of windows, flower peddlers swung their wares above the onlookers heads, and rickshaw men stood behind their shaky carts and gazed in wonder. Even the people on the river boats plying the Kunming canal pulled their craft to the shore and joined the festivities.

All along the convoy's slow-moving, crowded way the Chinese people, with thumbs up, and eternal grins spread over their faces, shouted their boundless, everlasting ding-haos. Governor Lung wound up the jubilee by putting on a banquet at city hall in honor of Pick.

Pick, back in Burma, prepared a two-color card certificate with a Ledo Road insignia to give to every member of the convoy. It certified that each man "was a member of the first overland convoy to break the blockade of Jap armies and deliver successfully war material to Kunming, China. The convoy left Ledo, Assam, on January 12, 1945, and reached Kunming on February 4, 1945. In traversing the China lifeline formed by the Ledo and Burma Roads, the convoy traveled 1,079 miles of the toughest driving in the world." Space was left on the beautifully engraved and printed card for the signature of Pick the Stick.

A certificate to be given to those who rode the length of the road after it opened came from the inkwell of Melvin W. Shaw. Designed after the manner of Neptunus Rex' testament for those who crossed the equator, the handsome Stilwell Road testimonial was for men who had the good or bad fortune to beat the seat of their pants all the way from Ledo to Kunming.

Shaw's certificate traced the route pictorially, complete with jungle, mosquitoes, pagodas, 6x6 trucks, hairpin turns, walled cities, and all the rest of the wonders of that route. In the upper left-hand corner, Uncle Joe gazed out of his GI glasses in front of a CBI patch, and happy-looking truck drivers of the various nationalities grinned from the lower right.

Cowboys, cockpit drivers, 6x6 gear strippers, jeep skippers, and even passengers with deadened posteriors were eligible for one if they made it all the way.

|

This account of the first convoy over the Ledo and Burma Roads from India to China is excerpted from Book 1 of William Boyd Sinclair's ten-volume series on the China-Burma-India Theater, Confusion Beyond Imagination, as published in Ex-CBI Roundup, June and July 1989 issues. |