|

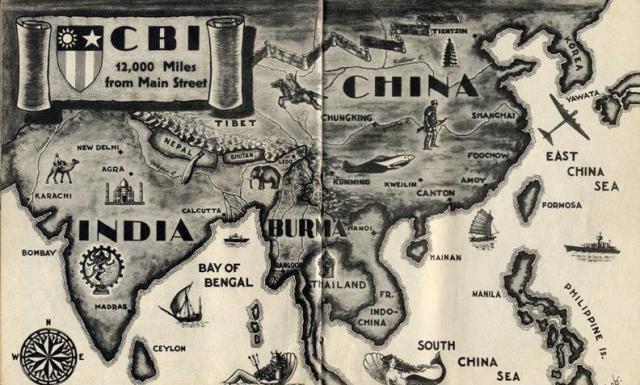

A souvenir booklet specially prepared for U.S. Army personnel in China, Burma and India.Pre-censored for mailing.

|

Introduction

Once upon a time there was a young American living in one of the more pleasant parts of the United Stateswho received a very personal and friendly letter from a group of his friends and neighbors.

It was an important letter because it said that these friends and neighbors had decided that it was necessaryfor him to go out with a bunch of other young men and fight his country's enemies for a while.That way, the letter said, we'd keep our country swell to live in and maybe have a peaceful world for many many years. The letter ended with a polite invitation for him to jack up his car, kiss his girl and come live for now with Uncle Sam.

Now it happened that the young American to whom this letter was addressed - his name was Albert Jones - was a very lucky young American. Many of his friends, who had received similar hospitable letters,were shipped to such places as England and Africa and little islands in the Pacific which nobody hadever heard of. But lucky Pvt. Albert Jones embarked on a fine fat steamer and almost before he knew ithe found himself in the middle of what was then the China-Burma-India Theater of Operations.

Albert did some fighting there. He also did some desk work, some truck driving, some flying, some road-building, some wire stringing, some pipeline laying, and for a while he clerked at thePost Office and in the Dispensary. He was luckier than some of his friends in one final respect,he didn't get hurt.

But what Private Albert Jones wants to remember later on, when his wife drags his moth-eaten ODs orsuntans out of the closet for the annual Veteran's Convention, is not the danger and the drawn-outboredom of his fighting and his work. He wants to remember his magic carpet travels in the Orient -the time he flew over the Hump, the strange animals he'd never seen before, the nice smiling facesof his Chinese friends, the wild jungle country around the Ledo Road, and the splendor and squalorof magic India.

YANK's "Magic Carpet" is not a history of the United States Army in what was the China-Burma-IndiaTheater. It doesn't attempt to "cover" CBI with pictures of each outfit. It's a souvenir booklet forPvt. Albert Jones, all about the CBI things he wants to remember.

INDIA

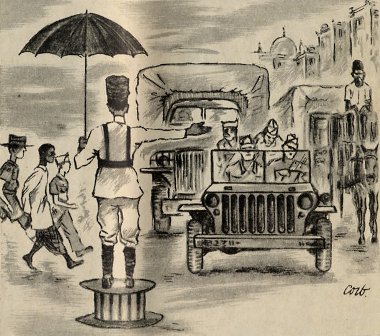

How well you remember that first sight of India as your ship glided into Bombay harbor - or Karachior Calcutta - and the heat and sights and smells of the country wrapped themselves around you like a new skin, a skin you knew you would not shed for many many months or years.

But you were anxious to get ashore. You'd had enough of that loose queazy feeling in your stomach, thejam-packed living conditions and the shipboard food. The stopovers at the Atlantic or Pacific portshad been fun. But now you wanted solid land under you for a while and a permanent station so you couldstop living out of a barracks bag.

Maybe when you began you're magic carpetbagging through India to your new station you got the feelingthat this ancient country was very like the United States in geography and climate - only more so.

Maybe when you began you're magic carpetbagging through India to your new station you got the feelingthat this ancient country was very like the United States in geography and climate - only more so.Like your homeland, India was a vast and varied country of mountains and deserts, of swamplands andfertile plains, of great rivers and of big and little cities. But the fiery deserts of Sind andBaluchistan were hotter, bigger, drier and more desolate than the Mojave. The Himalaya Mountainswere higher and colder and more jagged than the Rockies, and a lot more dangerous to fly over. Theblast oven heat of Assam or Agra or Karachi was more relentless than Arizona or Louisiana in July.No New Jersey mosquito ever had the wing spread or firepower of a Ledo anopheles.

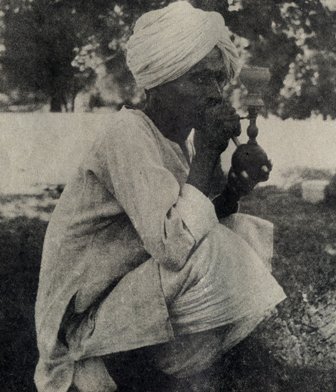

You might also have stopped to think that just as the United States is a melting pot of the Western races, so is India a compound of Oriental races. What a mixture of races, costumes, customs, culturesand religions! The Hindus of many castes, wearing their comfortable cheesecloth dhotis, gentlebelievers in humility, non-violence and a complicated 24-hour-a-day religion. The Moslems, believersin one God, Allah, eager to convert the infidel, wearing dhotis and also fezzes or turbans. The Sikhs,bewhiskered and beturbaned giants, big city policemen, drivers of taxis. The Parsees, shopkeepers andbusinessmen, dressed in neat white house coats. The Gurkhas, stocky bronzed toughs carrying scimitar-like kukri knives, feared by the Germans and the Japanese as the fiercest soldiers in Allied armies.The uncounted millions of India's "untouchables," living a semistarved existence in shack towns outsidethe cities, begging pitifully for baksheesh as your train makes a stop at a small watering station.

You might also have been suddenly struck with the eerie feeling that this, the ancient East, was Bible country. The deserts, the mud villages, the wooden two-wheeled carts drawn by camels and bullocks, the babel of many languages, the barbaric dress of men and women of many races - these primitive ways werethousands of years old. This must have been the way things were when Christ walked the earth. On manya village street, squatting or standing or working at their trades, you saw men with delicate religiousfeatures, a coarse black beard, a lean ascetic body and the strong black eyes of the religious mystic.

You might also have been suddenly struck with the eerie feeling that this, the ancient East, was Bible country. The deserts, the mud villages, the wooden two-wheeled carts drawn by camels and bullocks, the babel of many languages, the barbaric dress of men and women of many races - these primitive ways werethousands of years old. This must have been the way things were when Christ walked the earth. On manya village street, squatting or standing or working at their trades, you saw men with delicate religiousfeatures, a coarse black beard, a lean ascetic body and the strong black eyes of the religious mystic.What are the things you'll remember best about India? You won't forget the smells - the animal odorof fresh hides on a bullock-drawn two-wheeled cart, the musky odor of curry wafted into your Jeep as youdrive past a food shop on a back street, the cooling salt air blown into the docks as you work s ship,and the acrid stink of the bad-mannered camel.

You won't forget the gleaming marble mystery of the Taj Mahal at Agra, so much bigger than you hadthought and quite as beautiful in line and color and form as you had imagined.

You'll remember the Indian coolie, that brown scrawny man about the size of an underfed American boy;how he pulled you in a ricksha for miles at an unbroken trot; how he and six others carried a grandpiano on their heads down a city street, and how he groaned and sweated, doing the bullock's workpf pulling great weight of rice bags from the docks to the godown.

And you'll remember some beautiful Indian women - the tall Sikh girls in their loose white pajama pants,the doelike Hindus in their warm colored wrap-around sarees which reminded you of Western negligees;Moslem beauties decked out in gilt, silver and silk for a religious festival; and perhaps the round gentleface of a Burmese refugee working as a secretary in a headquarters office.

It will be a long time before you forget Assam - the mosquitoes, the dhobi itch, the swamps, the damnedwet heat, the snakes, the elephants, the insect-ridden bamboo bashas, building the roads, towing theCochran gliders into Burma, making the food drops, and the time the sky turned into a waterfall duringthe monsoon rains and your camp area was a mud lake for a week.

It will be a long time before you forget Assam - the mosquitoes, the dhobi itch, the swamps, the damnedwet heat, the snakes, the elephants, the insect-ridden bamboo bashas, building the roads, towing theCochran gliders into Burma, making the food drops, and the time the sky turned into a waterfall duringthe monsoon rains and your camp area was a mud lake for a week.You'll remember the trains and the noisy colorful chaos of the railroad stations. You'll remember that jostling ride in a Delhi gharry in the moonlight, the horse clopping lazily along the clean paved street,the gharry-wallah singing to himself a mournful Indian melody in a minor key. You'll remember betel juice,and pan, and Pattycake Annie and her dung pies. You'll remember very well the time you flew up theBrahmaputra and the monsoon weather bounced your transport around like a paper kite and just after yourplane's wheels hit the wet steel landing mats at Chabua the ceiling closed in solid with clouds and mistand rain.

What will you tell them back home about your service in India? You'll have memories of hard work, loneliness,discomforts and a few pleasures. They'll ask you about the Taj Mahal and the elephants and the burning ghatsand about the times the Japs came over. You'll tell them a few things - about the Taj, about the roughtimes on Chowringhee. Maybe you'll make modest reference to your charpoy wounds but mostly you'll bequiet - because you won't be able to put into words the color and size and variety and magnificence andpoverty of magic India.

BURMA

The convoy burned up the road out of Ledo, the Negro GI "pilots" handling their big trucks as if they werejeeps, expertly turning time into miles.On a hill the trucks stopped for a minute. The driver said this was Pangsau Pass and that ahead, justbeyond the pass, was Burma. So you climbed a rock in India and looked east at the long green Burma wayto the backdoor of Tokyo. The view was beautiful, there was no denying that. The rolling hills coveredwith green matted jungle stretched out to the low orange clouds on the horizon, the green graduating intoblue in the far distance, and from the valleys rose thin curtains of steam, giving the whole landscapea misty primitive poetic look as it baked in the yellow sun.

Later, when you really got into Burma, you saw the other side of the coin too. You saw the hill country,the malarious and tangled mountains, which were so "impassable" that nobody ever got around to building a road through them until you and your gang came along and built it out of sweat and blood and militarynecessity.

Later, when you really got into Burma, you saw the other side of the coin too. You saw the hill country,the malarious and tangled mountains, which were so "impassable" that nobody ever got around to building a road through them until you and your gang came along and built it out of sweat and blood and militarynecessity.The people you met were not the Burmese, who lived mostly in the flatlands of central and southern Burma.You met white men, brown men, yellow men and black men who had come from far countries - the British,the Indians, the Chinese and the West Africans. But of the native inhabitants of Burma you met onlythe mongoloid hill people - the Nagas and the Kachins.

The little brown Nagas, you were told, were headhunters. They were not very sociable and for the most partstayed in their hills. But the only foreign heads they took were Japanese and they could be trusted tosearch the jungles for bailed-out American fliers and to bring them safely back.

The Kachins were not quite as brown as the Nagas, were taller, and took more easily to hanging aroundAmerican troops and to picking up words of English, as well as American cigarettes. They were insectworshippers, and each Kachin village had its shrine for the crawling and flying things of earth, oftenit was a bamboo pole on top of which was a little receptacle holding food for gnats, or a low table-likeaffair holding food for ants. The Japanese soldiers had orders to shoot the Kachin on sight, for theyacted as junglewise guides for Allied troops and, armed by the Americans and British with tommy guns andgrenades, they infiltrated into enemy territory and had become experts at ambush.

You learned about leeches in Burma, and how to make these blood-sucking pests drop off your skin by nudgingthem with a lighted cigarette. You learned about mosquitoes and ticks and mildew and care of the feet andkeeping your mess-kit clean so you wouldn't get dysentery too often. Monkeys you saw and heard by thehundreds, bounding and swinging over the roof of the jungle. Their staccato baby-like barking was a handyalarm when Japanese patrols were around.

You would always remember how, even on the hottest days, the jungle trails, overhung with vegetation,were wet and slippery underfoot. You would remember the monsoon rains, those dreary gray months whenevery leather thing you owned including your wallet mildewed and rotted, when building a fire was almostas tough as building a bridge, when you lived on hills because every valley was a river and every rivera swirling torrent.

You would always remember how, even on the hottest days, the jungle trails, overhung with vegetation,were wet and slippery underfoot. You would remember the monsoon rains, those dreary gray months whenevery leather thing you owned including your wallet mildewed and rotted, when building a fire was almostas tough as building a bridge, when you lived on hills because every valley was a river and every rivera swirling torrent.You would remember the droning of transport planes circling over your jungle clearing, and the heavy thudof food and of grain for the mules and of ammunition as they dropped from the planes onto a rice paddyand the parachutes collapsed.

You would remember the Kachin women gathering up the parachutes from the fields and making turbans and blousesand sarong-like lungyis from the gay-colored rayon. You would remember 12-inch orchids growing in thecrotches of strange trees.

But you would remember best little memory pictures coming back to you in slow motion like scenes from a movie. The time you saw Dr. Gordon Seagrave, author of "Burma Surgeon," sitting stolidly in his jeep atMyitkyina air strip waiting for a covey of his Burmese nurses to fly in from another area. The tiny tan girlsarrived, dressed in pastel-hued lungyis, and stuffed themselves happily into the jeep, all seven of themfitting in without crowding, swirling around the impassive Seagrave like chicks around a mother hen.Seagrave, unspeaking and tired-looking in his dirty khaki clothes, drove them away, toward a frontlineaid station, the girls gay, giggling and chattering in their soft, strange tongue like a conventionof excited chipmunks.

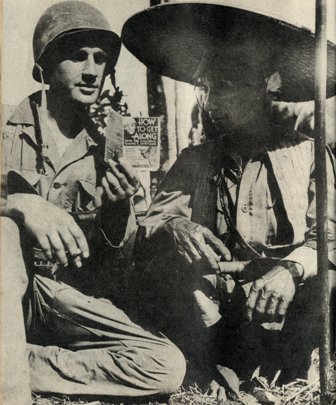

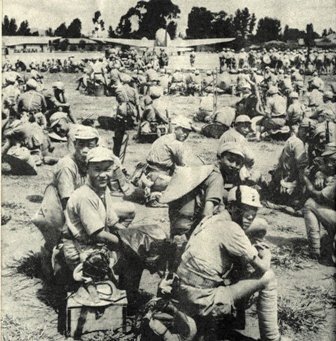

You would remember one afternoon when you and your buddies bathed in a clean smooth-flowing streamnear Walabum, splashing around naked in the cool water under the oblique sun. Washing themselves with youwere a couple of dozen Chinese infantrymen. Some of Merrill's boys had their mules in the river andwere washing them, and a few Chinese and Americans were squatting together under the shade of a bamboothicket on the shore, washing their battle-worn uniforms on flat rocks.

But it was a long slow march through Burma, and the lazy beautiful Burma you had read about in Kiplingyou never got to see. Perhaps as the campaign progressed you would see the Moulmein Pagoda, the lush deltaof the Irrawaddy and the end of the road to Mandalay. But if these sights were to be seen by other soldiers,you could still figure that in Burma you had seen and done plenty.

CHINA

You had heard stories about how tough flying the Hump was - about unarmed transports being jumped byJapanese fighters, about immense uncharted mountains looming up through the clouds, about freak plane-killingweather, about motor failures and bailouts.

But when your turn came, everything went pretty smoothly. The first sensation you and your fellowpassengers had was one of comfort and pleasure at forsaking the moist heat of Assam for the coolness of theair over northern Burma. The big plane gained altitude steadily, lifting itself over gigantic thunderheadsand over oceans of billowing cumulus which, with the sun on them, looked blindingly white, like incandescentsnow.

Through breaks in these clouds you got to see the soaring jagged and awesome peaks of the Himalaya Mountains,the highest ones covered with snow. Perhaps you caught a glimpse of the Burma Road, a corkscrew of orangedirt gashed into the convolutions of the green mountain range. You wore an oxygen mask and were cold anduncomfortable.

Through breaks in these clouds you got to see the soaring jagged and awesome peaks of the Himalaya Mountains,the highest ones covered with snow. Perhaps you caught a glimpse of the Burma Road, a corkscrew of orangedirt gashed into the convolutions of the green mountain range. You wore an oxygen mask and were cold anduncomfortable.But when the plane skimmed over that last great mountain and you first saw below you the neat checkerboardpattern of the terraced earth of China, greens and browns and rice lakes gleaming in the sun, your excitementreturned. For this was ancient and fabulous China, this was adventure, this was as far away from the goodUnited States as any man could travel on this earth.

You found that GI life in China was neither soft nor hard, that there are in the world better and worse stations. Perhaps your first quarters were in a hostel with a tile roof turned up at the eaves andcorners like the China you expected from looking at Chinese prints and reading Pearl Buck stories.However, your romantic roof leaked when it rained, and the mud walls of the building cracked and buckled.Sharing your quarters were spiders, big mosquitoes, fat rats and maybe fleas.

You also learned what the years of blockade have meant to China. For now you too were cut off from the restof the world by the Japanese, by the world's highest mountains, by the wastelands of Mongolia. You too beginto experience that walled-in feeling. Your mail arrived late. Unlike GIs at almost all other stations inthe world, you didn't get a beer ration. Your food was not Stateside, and you ate water buffalo steak, eggs,rice, cucumbers and corn till they came out your ears.

You also learned about inflation, and though your financial difficulties were minor compared to those ofChina's hungry millions, they were none the less annoying. You found that China was one of the few placesin the world where the American soldier was not a relatively rich man. A good restaurant meal cost you twoto four American dollars. A 20-minute ricksha ride nicked you for 50 cents to a dollar.

Your fun was pretty scarce. Your stay in China was a long monotonous grind for the most part, and towardthe end it got so you felt you'd been in China all your life. An American woman was something to look at,like a ricksha on Broadway. You saw an occasional nurse, a Red Cross hostess, a U.S.O. showgirl, a marriedand middle-aged missionary. But that was about all. You did manage to date that English-speaking secretaryof the OWI in Chungking. She was a refugee from Shanghai, very gay and pleasant, very pretty in her tightsilk gown cut high at the throat and slit at each leg. But then you were transferred to an airbase in Kwangsi Province and anyway she had begun to go out with a Major.

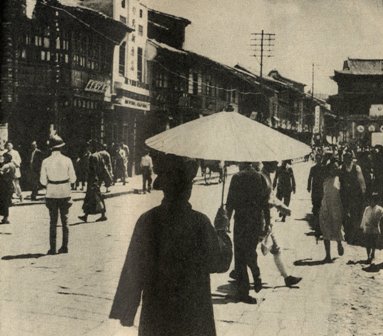

You would remember the heat and the shaky bombed buildings, the cave shelters and the crowded hilly streetsof Chungking. You would remember Kunming - Gold Street, shop-filled "GI Street," and riding a rickshaover the rough cobblestones. You would remember the ancient walled city of Chengtu, so close to Tibet, soprimitive and untouched by Western culture until the Air Corps flew in.

You would remember the heat and the shaky bombed buildings, the cave shelters and the crowded hilly streetsof Chungking. You would remember Kunming - Gold Street, shop-filled "GI Street," and riding a rickshaover the rough cobblestones. You would remember the ancient walled city of Chengtu, so close to Tibet, soprimitive and untouched by Western culture until the Air Corps flew in.You would remember the pleasant tree-bordered streets of Kweilin, before the pillboxes were set up in thestreets and the airbase had to be blown up and evacuated. You would remember the green Szechuan countryside,China's rice bowl, and the peasant women working thigh deep in the paddy waters. You would remember thatsmiling ferryboat boy, he couldn't have been more than ten years old, who poled you across the river atHsinching. You would never forget the sight of a thousand coolies pulling a ten ton roller over the B-29fields, mass labor, the kind of mass machineless sweat that built the Great Wall of China and the Pyramidsof Egypt.

You'd remember a lot of other places too, names which before you came to China were funny-sounding andoutlandish, but were now as familiar to you as Evansville or Schenectady, names like Yunnanyi, Lungling,Hengyang, Changsha, Kweiyang, Chuanhsien, Paoching, Fow, Yochow, Hankow and Tung Ting Hu.

You would remember the time one of your Chinese friends invited you for dinner at his home. You met his cute little wife there and sat down with them at a low table loaded with an array of steamed chicken, whiterice, fresh well-cooked vegetables, sweets and tea. You did your best with the chopsticks, but fell so farbehind on the several courses that your hosts insisted you put down the chopsticks and eat with the porcelainspoon-like scoop which was used to dish out the rice. You put away four full bowls of food. After the mealyou passed around American cigarettes and sat back with a contented feeling in your stomach which you hadn'thad since your last good Stateside feed.

What would you take home from China? Souvenirs, of course - that silver water-cooled pipe you bought inChengtu; those rice bowls of flexible Foochow lacquer you bought in Kweilin; that brocaded and embroideredMandarin coat you'd acquired for $100 U.S. as a gift for your girl or wife; that jagged bomb splinter youpicked up from Hengyang field.

What would you take home from China? Souvenirs, of course - that silver water-cooled pipe you bought inChengtu; those rice bowls of flexible Foochow lacquer you bought in Kweilin; that brocaded and embroideredMandarin coat you'd acquired for $100 U.S. as a gift for your girl or wife; that jagged bomb splinter youpicked up from Hengyang field.But mostly you would take back memories. You would never erase from your mind the months of work, of combat,of boredom and of loneliness. But you would also remember that quiet Sunday afternoon when you visitedthe Buddhist temples with that Chinese girl from the local university. You would remember driving thatbattered and heavily loaded truck to the Salween front through the wild and beautiful mountains of Yunnan.

One thing you would always remember about China, despite the difficulties, was the broad smile and thethumbs up "ding hao" of the Chinese in every walk of life. You got that "ding hao" and that friendly smilefrom the Chinese foot soldier on the march, from the farmer in his paddy, from the ricksha coolie, evenfrom tiny children barely able to walk.

And you looked forward to visiting China again after the war, to putting your wife and kids aboard acomfortable ship at San Francisco and sailing with them to Shanghai or Canton. Or perhaps you would fly,with a stopover at Tokyo.

You wanted to see the big city China, the China the enemy occupied during your service. You came to Chinathrough its back door and got to know it, its people, its farm country, its back yard, with an intimacythe ordinary Western tourist never had. You and China had been campaigners together. You looked forwardto visiting China's big cities in peacetime in the same way you looked forward to visiting the comfortableStateside home of a GI friend you met for the first time in a China barracks.

Adapted for the Internet from the original 1945 booklet YANK's Magic Carpet

Copyright © 2004 Carl Warren Weidenburner

TOP OF PAGE INDIA BURMA CHINA MAP

ABOUT THIS PAGE CLOSE THIS WINDOW

Visitors

Since October 31, 2004