Stilwell Road - Land Route to China By Nelson Grant Tayman Today hundreds of trucks in steady procession are carrying the sinews of war over the Stilwell Road, the Ledo-Burma Road which was renamed by Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek in recognition of General Joseph W. Stilwell. These heavily-laden trucks are dramatic proof of U.S. Army Engineers' resourcefulness. The town of Wanting, on the China-Burma border, recaptured from the Japanese in January, 1944, may be likened to a beachhead. It is China's "back door," opening wide the land route of invasion. The Stilwell Road, China's new lifeline, is a combination of the new Ledo Road, built by the U.S. Army Engineer Corps, and the Chinese-held portion of the old Burma Road. The Ledo Road links northern India and Yunnan

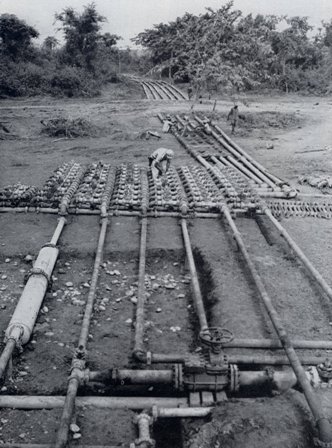

I had a part in its building, for I spent three months in Burma and China, determining the type and location of major bridges on both the Ledo and Burma Roads. Roads are indispensable to the network of communications and supply which is essential for a sustained offensive against the Japanese in China. Flying "the Hump" Before the Stilwell Road was opened, every ounce of fuel for the B-29's, equipment and supplies for our Army, and critical materials for Free China's 200 million fighting men and civilians had to be flown to their Chinese destinations over one of the world's loftiest mountain ranges. "The Hump" our aviators call this hazardous section of the route between India and China. Peaks towering 15,000 feet are common; many rise more than 17.000. To negotiate the crossing, planes frequently climb well over 16,000 feet. This air lift means costly transportation. A Liberator bomber, serving as an aerial "oil tanker," starts from an Indian base with four tons of gasoline. By the time it climbs skyward, crosses the Hump, and descends to its destination, it has only one ton of fuel available for delivery. Its motors eat up the other three making the round trip. Today a pipeline reaches far into Burma and soon will extend across that country into China. This pipeline now carries aviation gasoline from Indian ports directly to air bases near the China border. The story of its construction through the jungle rivals in romance that of the Ledo Road. When I was in Burma I saw the pipeline being built. C-47's flew the pipe into the jungle. I saw pumping stations going up along the line. U.S. Army Engineers conceived this idea more than two years ago. Pipeline, pumping equipment, and engineer building methods have all been battle-tested in Africa, Italy, France, and the Pacific. Before the Japanese occupied Burma, supplies for China from overseas were unloaded at Rangoon, sent northward by rail to Lashio, and then were transported to Kunming, Yunnan Province, over the Burma Road, China's lifeline. With Burmese ports and the railhead at Lashio in Japanese hands and the Burma Road cut, a new route had to be mapped. So American supplies were unloaded at Calcutta, sent by rail up the valley of the Brahmaputra to numerous airfields, and then flown across the Hump. New Road Starts at Ledo The rail line from Calcutta ends seven miles east of Ledo, Assam, where the new Ledo Road begins. Crossing the Patkai Range into Burma, the highway pushes southward toward Mogaung, Myitkyina, and Bhamo. As fast as jungle was cleared of Japs, U.S. Engineers extended the road, until it hooked up with the old Burma Road east of the Irrawaddy Rover. Together with the string of airfields which make possible the air supply route across the Hump, the Ledo and Burma Roads (now jointly called Stilwell Road) form the skeleton around which we are building the structure for large-scale operations. I traveled with Lt. Col. George H. Taylor, of the War Plans Division, Office of the Chief of Engineers. We left the United States in January, 1944, flying by way of Brazil, Ascension Island, Africa, Arabia, the Arabian Sea, Karachi, New Delhi, Agra, Calcutta, and Chabua, one of the airports from which our flyers take off to cross the Hump. I could have continued on to Ledo by rail, but I chose the lesser of two transportation evils and went by jeep. The railroad, of meter gauge, is equipped with little 5-ton-capacity wagons and third-class coaches. Every train that pulled out of Chabua was jammed with natives. An American soldier with whom I watched one of these trains chug away remarked, "They ride everything but the whistle!" Incidentally, there is a sign in the Army recreation hut at Chabua telling GI's they may take away any magazine except the National Geographic.

The highway from Chabua to Ledo is a one-way affair, surfaced partly with asphalt. The road winds through rolling countryside past hundreds of tea gardens, each fenced and planted in orderly rows. Laborers among the green, hedge-like plants worked with one hand while the other gripped an American-made sun umbrella. Most of the tea-plantation laborers were natives of the Darjeeling area. Except for small crews maintaining

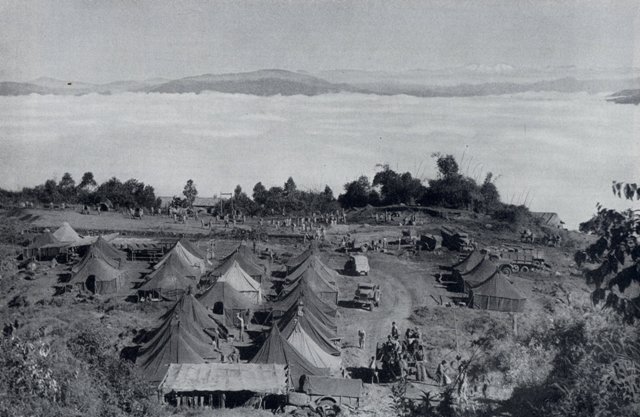

They toiled through the blazing heat of the dry season and the flooding rains of the monsoon with admirable stoicism. The work was tough, but they never complained. They were housed along the side of the road in village camps of bamboo huts which once quartered General Stilwell's Chinese troops. Elephants Help Road Builders At intervals along the Chabua-Ledo highway, I saw elephants hauling timber to the roadside for American trucks to carry off for use on the Ledo Road. The elephants are owned by native lumbermen under contract to furnish teak and other hardwoods to the U.S. Army Engineers. Ledo is a bustling little frontier town. Its relation to Burma today is somewhat that of Pittsburgh in colonial America. It is a frontier town, a jumping-off place into uncharted wilderness for the most part. And it has the atmosphere of a frontier town. In peacetime Ledo was the tea center of Assam. It had a normal population of 2,000, small but surprisingly cosmopolitan. There were British tea growers and other commercial representatives, natives of Assam and other Provinces of India, and a scattering of Mongols, Tibetans, Burmese, and Chinese. The main street, lined with native bamboo huts and tin-roofed godowns, the tea storage houses, parallels the railroad from Chabua, about 40 miles away. Ledo is the end of the long rail supply line from Calcutta up the Brahmaputra River Valley. The tea business is at a standstill now because the needs of war must be served first. The real business activity of Ledo has shifted to the native bazaar, covering three blocks of one of the side streets. The natives, thanks to the Ledo Road, now have more money than they've ever seen before; trading is brisk. I bought some shoe polish, paying 95 cents for a can which would have cost 10 cents in the United States. Even then I had to dicker a little. The seller asked $1.25. The variety of goods for sale is amazing. Traders come from Tibet with hides. Large quantities of

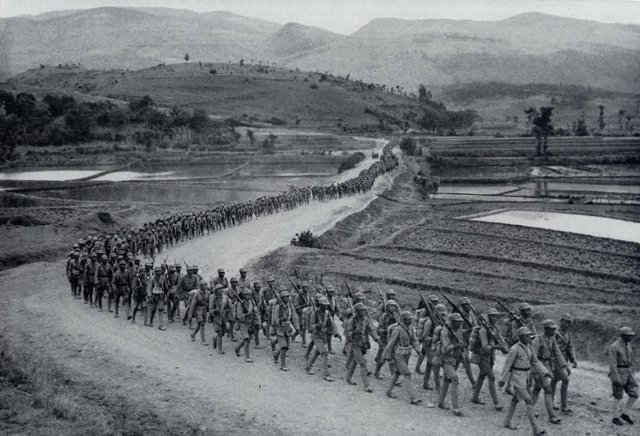

Good customers are the American Negro Engineer troops and Chinese troops who came out of Burma with General Stilwell on his epic retreat of 1942. These Chinese soldiers, under American command and fed and clothed by the United States, showed an average gain in weight of 25 pounds soon after they arrived at Ledo. Trading was in British, United States, Chinese, and Indian money, but none of this currency was so sought after as Japanese invasion money once the Negro troops discovered it was for sale. So eager were these lads to buy up the worthless Japanese currency, brought into Ledo by enterprising Chinese merchants, that they were willing to pay up to $3 for a single bill. They wanted to send the money home as souvenirs. I brought back with me several Chinese $100 bills - worth about fifty cents each when I arrived in the United States. The Ledo Road starts with the main street of the village of Ledo, a stretch of ten miles which the British improved with some asphalt covering. Before the Americans arrived, the highway beyond this section was little more than a foot trail snaking off into the Naga Hills. Now there is a wide graveled highway to take the heavy loads of military convoys. The colorful Naga head-hunters who live in the hills around Ledo bear a striking resemblance to our own American Indian. They have the same copper coloring, high cheekbones, and hooked noses, and they walk with a natural grace. Whether in the wilderness of the hill country or in town, they habitually move in single file. The men wear loincloths; the women, varicolored sarongs and shawls. It is almost a breach of etiquette for a Naga to be caught without his knife, a murderous-looking weapon with a 20-inch blade that curves toward the end and is even more formidable in appearance than the storied Gurkha knives which have slit many an Axis throat in this war. Some Nagas also carry quivers of blow darts. Although intended for hunting animals, Naga darts have been found in dead Japanese in the jungles of eastern Assam. Nagas Rescue American Airmen The Nagas like Americans. One reason may be the offer of one hundred rupees for every Allied flyer rescued from the jungle. With nice impartiality, the Nagas also are willing to supply Japanese for the same fee. While I was at Ledo I saw a group of Nagas bring in seven American airmen who were forced to parachute

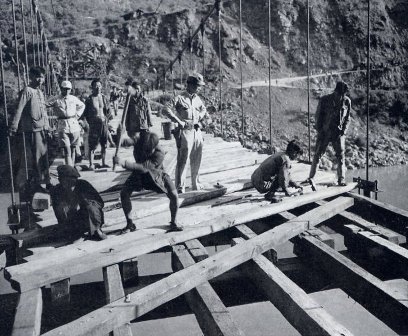

These Nagas were feted and paid their seven hundred rupees of silver. Then, instead of beginning their hike back up to the hills, the group lingered so long that someone asked why they didn't go home. Their spokesman said they wanted to see the nesting place of the "roaring giant birds" that flew over their country. The Naga delegation was taken by motor to an American airfield. The loin-clothed visitors stood with folded arms in complete silence for fully half an hour as they watched the big planes land and take off. Only visible sign of excitement was the increased tempo of their jaw movements as they chewed betel nut. Then, their curiosity satisfied, they fell again into single file and returned to the jungle. Isolation is ended in Upper Burma, too. Naga tribesmen got a close-up of a B-29 Superfortress while it was still a mystery plane to Americans. Never in all my engineering experience, including Army service in the last war, have I seen anything to match the Ledo project for plain and fancy terrain problems. The road is carved out of earth; its foundations are earth; there is little or no rock to provide a solid roadbed. At numerous points it had to be contoured around mountains, where it resembles an earthen bench with sheer drops thousands of feet below and overburdens towering hundreds of feet above. The Road of 700 Bridges The mountains, devoid in all but rare instances of any rock formation, present pressing maintenance problems during the monsoon period. However, earthslides are easier to contend with than rockslides. Whenever a slide occurs, a bulldozer moves in to cut a new section of the road. Fortunately the slopes are heavily forested, a condition which to some extent retards slides. The Ledo Road passes over 700 bridges. Each bridge had to be built to withstand the annual monsoon.

I met a score of splendid Chinese engineers in Burma, including graduates of all the principal engineering schools in the United States. The preceding year's monsoon had washed out many of their bridges, but it was little wonder. Even Chinese engineers had never before built bridges in monsoon country. One reason I was sent to Burma was that I had had experience in building some 20 bridges in the Mississippi Valley - in Arkansas, Louisiana, Texas. To withstand Mississippi floods, bridge abutments and approaches must have sturdy footing. The same is true of Ledo Road bridges, for otherwise the monsoon cuts the earth from under the foundations. The Ledo Road crosses numerous small mountain streams to cut through the Hukawng Valley of northern Burma. There are major crossings of the upper Chindwin River which must be bridged, in addition to numerous lesser streams crossing the Hukawng Valley. The designs for these bridges were worked out in the field, using local material, largely timber, supplemented by United States Army equipment. Convoys were already rolling along that section of the road which had been completed, bringing up supplies both for the fighting forces at the front and for the road builders. The convoys moved on schedules that would be the envy of transportation experts in this country. This was due largely to a block system controlling the movement and maintenance of trucks. Prime nuisances in building the Ledo Road were the flash rains which break without warning during the dry season. Such a storm occurred while I was at a road camp near Shingbwiyang in Burma. A group of truck drivers from an American Negro Engineer outfit was there, seeking shelter from the sudden rain. One of the soldiers popped his head out of a hut, pulled it back, and, grinning, summed up his opinion: "Captain, this is the first time I've seen somethin' up here of what there was enough of." Nighttime provides a pleasant interlude along the Ledo Road. Chinese laborers, sitting on the hillsides around the camps, sing their weird Oriental tunes to the accompaniment of twanging strings and the liquid minor tones of wind instruments. They are also avid movie fans. Whenever a U.S. Army Special Service truck comes up the highway to put on a film show for the Americans, the Chinese and Burmese come down to watch. Many films shown along the Ledo Road have not yet been released in this country. The Chinese laborers have their own cooks. They wear their own clothing, nondescript and in all the colors of the rainbow. They eat twice a day, in the morning and at night, in keeping with native custom. At work they are divided into groups of 30 to 70, supervised by American noncomms.

American Plantation Songs in Burma The Negro Engineer troops, who have done a marvelous job as tractor and truck drivers, also lend enchantment to the night with their singing of the old familiar plantation songs, with an occasional excursion into the field of "boogie-woogie." When I was there, a musical program by these American Negroes in remote Burma was broadcast in the United States. I went as far as I could along the Ledo Road, right up to the jungle foxholes at its forward end. Then I returned to the Assam airfields to fly over the Hump and visit the Burma Road. The Hump is considered by pilots the toughest air route in the world and they're willing to wager their flight pay on that. I wouldn't bet with them because I would have lost. We had twenty-eight passengers on the plane which was to take me to China. Thirty minutes out, when we had climbed to a height of more than 15,000 feet and were sucking oxygen, one of the engines conked out. The pilot banked his plane around carefully and, nursing his one good engine, sent us into an oblique dive back to the airfield. At Kunming, Chinese terminus of the air transport over the Hump, I was stationed at the old Flying Tigers headquarters in the ancient agricultural college. The walls are still adorned with the trophies of air victories over the hated Japs. Here I began to note the contrasts between the two roads. The Burma Road west from Kunming isn't a Lincoln Highway, and it wasn't built that way. In many places it is nothing more than a refinement of the ancient Marco Polo trail. The improvements and maintenance on this highway were accomplished with the blood, sweat, and tears of the humble Chinese who live along its tortuous route. When the Chungking Government realized the urgent need for a highway to keep the Chinese back door open to the outside world, it called on the Governor of Yunnan Province, Gen. Lung Yun, to complete the Burma Road. Thousands of Chinese worked right through the monsoon periods. Many died of malaria; but the job was finished in 1938, in record time of little more than a year. The Burma Road was really a hand-built highway. The Chinese Central Government directed the recruiting of this huge working force. Provincial governors received orders to produce squads of workers. They in turn communicated with village magistrates, who rounded up their quotas. I learned that nearly every community was in reality a family group. In the ancient walled town of Yungping, for example, I found that all the 4,000 residents belong to the communal family. Authority is vested in the family elder, who is the magistrate. When the governor of Yunnan Province wants a levy from Yungping for his provincial army, or for the National Army, or for road building, coal mining, rice field work, or similar large-scale enterprises, he simply advises Yungping's magistrate to supply the town's quota. That's the way labor in China has been drafted for thousands of years.

Coolies Take Place of Bulldozers To build military roads the U.S. Army allots so many bulldozers to one area, so many more to another. In China, when generals build roads, they have no bulldozers to allot; so they draft men to take their place. I visited the coolies at lunch and at dinner and usually found them eating rice seasoned with pepper. Groups working near rivers were fortunate, for they could set fish traps. At night they slept on the ground in caves or beneath rude bamboo shelters. Working methods were primitive. First, the coolies would pry loose from fissures and stream banks, or dig out of the ground, big rocks weighing from 60 to 75 pounds. These "one-man" boulders they would lug to the proposed roadway, sometimes 500 yards away, and lay as a rough foundation pavement. Then, in baskets, wheelbarrows, and slings, they would bring smaller rocks to wedge into the spaces between the big ones. Gradually they built up this rock base, using smaller and smaller stones as it grew higher. Roadbeds were graded by hand with an ordinary builder's water level. The final layer was of mud-moistened earth of western China, which has a bonding quality similar to Texas adobe. This earth was carefully worked down into all crevices and then smoothed on top. The finished product was closely akin to what United States road builders call a telford base. Rock excavation took a high toll of Chinese lives. Black powder was used for blasting. Instead of detonators, the Chinese made fuses of paper, soaked in oil and black powder and of uncertain timing. They jammed powder into the drilled holes with the back end of a steel hand drill. There were many explosions that brought sudden death to scores of coolies.

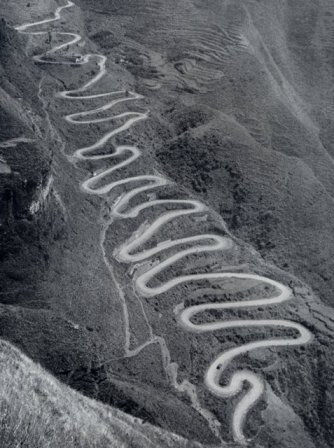

Burma Road Carved from Mountains Western China is developing a common dialect as a result of the mingling of people from widely separated districts. Prior to these huge building operations, inhabitants of one part of Yunnan Province could not converse with people from other sections. Now thousands can talk among themselves, no matter how far apart their homelands are. Carved entirely out of rock-studded mountains, the Burma Road reaches elevations as high as 8,500 feet. That section of it in Chinese hands is still in process of improvement. My trip down the Chinese portion of the Burma Road convinced me, however, that before it can carry heavy two-way traffic considerable realignment and reduction of grades will be necessary. The road has many curves, an average of four to the mile. Chinese officials seem reluctant to cut through paddy fields. Perhaps they feel that the rice produced is more important than a few miles of travel saved. Since my sole concern was with bridges, I examined with great interest the crossings built by Chinese engineers. They were, generally speaking, of good construction but designed to carry lighter loads than the American type. Bridges ranged from primitive types to elaborate stonework structures more attractive than utilitarian. It was spring along the Burma Road. My jeep would be rolling along a drab mountainside. Suddenly, around a turn, would come into view a lush green valley with the flooded terraced paddies sparkling in the sun. In the midst of such a setting would be nestled a Chinese village. I visited some of those Chinese communities. One night was spent in Yunnanyi, about 135 miles from Kunming. The village was crowded with evacuees from occupied China. Surrounded by a thick mud-brick wall with four gates surmounted by stone dragons, Yunnanyi has narrow, cobbled streets lined with little open shops. But the inhabitants are a cheerful lot. They are grateful for the help the United States has given China; and whenever an American appears the natives give forth with the Chinese equivalent of "O.K." - "ding hao" - and an upraised thumb. Even little children carried on their mother's backs raised thumbs in salute to passing Americans.

Salt Sold by the Chunk Often I encountered salt salesmen. These itinerant merchants set out from Kunming along the Burma Road with two large blocks of salt slung over their shoulders and held in place by thongs passed through holes bored in the blocks. The salesmen cut off chunks of desired size for customers and trudge along until the blocks have been completely sold. To sustain them on their journeys, they carry pocketfuls of rice. The salt comes from the huge wells at Tzeliutgsing, 110 miles west of Chungking. These centuries-old wells produce about 250,000 metric tons a year, or about one-fourth of all the salt mined in Free China. By the time my jeep returned to Kunming I had completed a thousand miles of travel on the Chinese-held portion of the Burma Road. Kunming, one of the largest cities of Free China, is as much a contrast to the Naga Hills wilderness as is the Burma Road to the Ledo Road. Its shops would seem incredible to ration-restricted Americans. How they got there is one of the mysteries of the war; but I saw and touched the latest-type American electric refrigerators, fountain pens, flashlights, thermos bottles, and watches. Housewives in America would buy them up in a hurry, but not at Chinese prices! Here are some typical inflation prices when I was there: fountain pen, $80 in American currency, or 16,000

A building boom has smitten Kunming. Modern homes were going up fast while I was there. They resembled American types, but each was surrounded by the traditional Chinese wall. In Kunming I saw mercenary troops recruited from many races - Malayans, Kachins, Karens, Tibetans, and a few Burmese among others - who fight on the side of the Chinese. One division was commanded by an Australian, another by a Hollander. Some of their officers were South Americans. All were soldiers of fortune fighting for adventure and gold. American Engineers Blast Ledo Trail I flew back to Ledo and then we started our homeward journey to the States. Reflecting on my trip, I recalled the Juxtaposition of old and new, of mountain jungle with centuries-old wagon road, of superbombers and blow darts, of Ledo and Burma and America. To me they all seemed symbolized in the career of one U.S. Engineer General Service Regiment at work on the Ledo Road. Composed largely of middle-aged men recruited directly from civilian road-building jobs on state highways

Most of them are veterans of the last war who fought in France. They fight this war on the other side of the world. Many are members of the American Legion. At an impromptu Legion Post meeting held while I was there, a former State commander and six former post commanders were present. These men all agreed that the Ledo job was 100 percent tougher than their Alaska assignment. Despite rain, mud, and malaria, they completed many precious miles of road. Not only did they operate the lead bulldozers in clearing the trail for the Negro troops to follow; they also laid down fighter strips for the use of tactical forces. At one airstrip site in the Chindwin area, Japanese mortar fire started falling on them. Unperturbed, they simply moved to the other end of the airstrip and continued their construction work. Two hours after the Japanese mortar fire had been knocked out, fighter planes were landing. Some day the saga may be told of the few pieces of American highway construction equipment which were left on the Chinese portion of the Burma Road when the Japs cut across the Burmese sector. The three bulldozers, the patrol grader, and the air compressor were out of order more often than they were in use. Many of the parts to keep them in running condition were hand-forged in homemade Chinese machine shops. The Chinese kept accurate records of the exact hours each piece of equipment was in operation and the amount of work done. With this dilapidated machinery, 30 American soldiers and 200 coolies did as much work in a trial period as 30,000 coolies with hand labor alone. Chinese engineers were delighted. Gradually additional pieces were flown to them over the Hump. Today the Chinese operators of compressed air tools are the aristocrats of the road-building army. Chinese engineers request road-building equipment by American model and trade names. What American and Chinese road builders have done together is an augury for the future. |