|

|

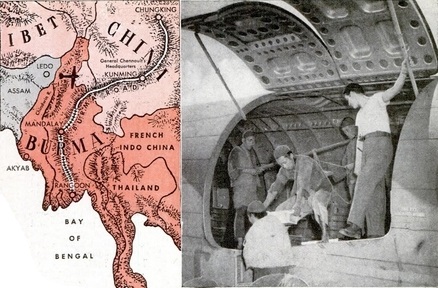

Air route from Assam to Kunming passes over the Burma "Hump" where peaks are hidden in fog.

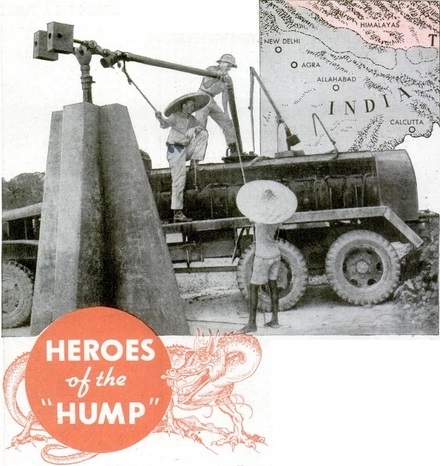

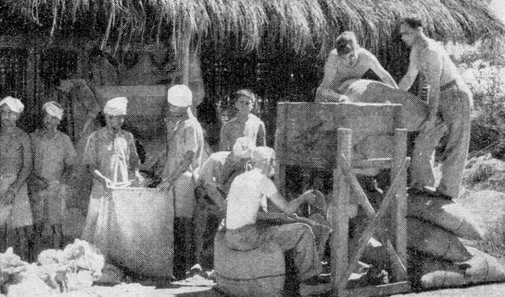

Left, native labor helps fill gasoline truck close by airfield.

Above, loading ingots of tin on a Curtiss C-46 at Chinese base for the return trip to India.

Below, air view of Burma Road held by Japs.

|

by Wayne Whittaker

FROM the crude loud speaker of the radio perched on a packing crate in the center of the bamboo hut came weird whistles and scratches. Eight pairs of ears belonging to American flyers reclining behind mosquito nets on four double-deck bunks, one against each wall, were cocked toward the speaker. Alongside the two barrack bags, rifles, steel helmets and gas masks beside each bunk hung the flyers' jackets bearing the insignia of the India-China Wing of the Air Transport Command. The only light in the hut was from a lantern suspended from a pole under the thatched roof.Soon a sing-song voice from Tokyo came through the scratches on the radio:

"Yesterday Imperial Japanese bombers in great force from advanced base Myitkyina in North Burma . . . (scratch, squeak) . . . thousands of tons of explosives on American airfields in Assam . . . American cargo planes all burn . . . China Wing of Air Transport Command wiped out . . . smoking ruin."

The guffaws of the men who fly the most dangerous air route in the world spread from hut to hut, from airfield to airfield in the network of bases in Assam, northeast corner of India between Tibet and Burma.

Tojo was always good for a laugh. The truth was that Jap bombers had dropped a few "eggs" on an airstrip yesterday and destroyed several cargo planes, but that was about the extent of the damage. And today - here was the joker - the commander of the "Hump" sector had sent out the largest tonnage of supplies that had ever been flown in a single day from India into China.

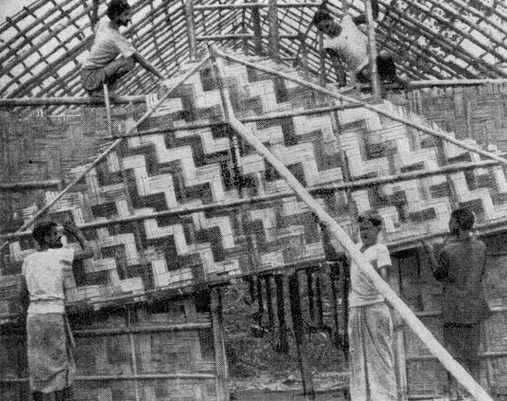

Natives erecting basha of cane strapped to bamboo poles to house Yanks

Natives erecting basha of cane strapped to bamboo poles to house Yanks

|

The amount of tonnage that went over the Hump that day is secret, just as it is every other day. But it can be revealed that the number of planes leaving the airfields of Assam daily for China is greater than the flights that come and go at LaGuardia Field. The India-China Wing today is the biggest single air transport operation in aviation history and its monthly tonnage of military supplies is greater than was ever carried by trucks over the old Burma Road.

Since the fall of Rangoon in March, 1942, and the closing of the Burma Road, this air line has been the only supply route to Maj. Gen. Claire L. Chennault's 14th Air Force in China and the armies of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. Critical cargo flown over the line includes aviation gasoline, ammunition, bombs, jeeps, trucks, artillery, small arms, airplane motors, spare parts, food and clothing. Every gallon of gasoline delivered costs about $20, and it takes three plane loads of fuel to put one heavy American bomber into the air for one raid on Jap positions.

The Hump route from Assam to Yunnan is 500 miles long, and veteran flyers say that every mile is a gamble with death. It gets its name from the subsidiary ranges of the Himalaya Mountains that extend into Burma, jagged snow-capped little brothers of Mount Everest that protrude into the clouds and mist at 18,000 feet.

Between the peaks are valleys of lush jungle and treacherous air currents which cause a plane to drop a couple of thousand feet in a minute.

|

In the so called winter months, the Assam lowlands are covered with fog through which the planes must find their way down. During the monsoon season, from March to October, there is a steady downpour of rain, and the "ceiling" during this period is seldom higher than 3,000 feet. Icing starts at 15,000 feet. Planes sometimes have to fly as high as 30,000 feet to get over the "weather." Clear weather is a hazard, too, for the big unarmed transports are then more easily spotted by the Japs. And to further complicate the pilots' problems, the mountains deflect radio beams dozens of miles.

This deflection of beams and an accompanying gale resulted in a unscheduled visit to "Shangri-La" by one of the crews. Their C-87 (converted B-24 Liberator) flew in snow and darkness for hours after losing radio contact with the base. When there was no gas left, the crew of five men bailed out and found themselves on a snowy peak in the forbidden land of Tibet. Flight Officer Harold J. McCallum later reported they were so close to the mountain when they left the plane that the parachutes barely had time to open.

Three of the men landed near enough to find each other by shouting above the whine of the blizzard. At daybreak, they were joined by the fourth member of the crew. The fifth man spent three nights alone. He lived on chocolate bars and quenched his thirst with snow.

Natives led the pilots to a village where an English-speaking Bhutanese monk lived. He housed them in his mud hut and contacted the Tibetan foreign minister who sent out a party to bring the flyers to the holy city of Lhasa. The minister arranged for a party to take the flyers by horseback to India. It took weeks to make the trip along narrow trails that wound among 25,000 foot peaks. After a short rest, the crew was back on the job.

|

Many of the men who have to bail out over the Hump or survive a crash, find their way back to India. When a crew is in trouble, its position id radioed back to the base. A rescue plane flies out, locates the lost flyers and drops them supplies by parachute. If immediate medical aid is needed, a flight surgeon bails out.

Teamwork by crew members of the India-China Wing is as highly developed as it is on the bomber that shuttle over Europe, according to Chaplain (Major) John. S. Garrenton, who recently returned after 22 months in Assam. Major Garrenton has flown over the Hump 32 times. He tells how the loyalty of one 17-year-old radio operator, a corporal, saved the life of his crew chief.

"The C-46 in which they flew was attacked by Japs who suddenly dropped out of the clouds," he said. "A burst of gun fire swept the cargo plane from nose to tail. The pilot and co-pilot were killed. The left engine was shot out and the right engine set on fire. The plane plunged from 17,000 feet in a mass of flame. Neither the young corporal nor the crew chief could jump because they were pinned to the floor of the burning ship by some heavy cargo that had broken loose.

"When the ship crashed in the jungle, it burst open and the two men were thrown clear. The corporal had only a few cuts and bruises, but the crew chief had a broken back and could not move. Placing water and food by the injured man, the corporal walked three days through the jungle to find help. He returned with native stretcher bearers and helped carry his chief to a village. There he sent up signals until a rescue plane was sent with a doctor who bailed out and remained with them all the way to a hospital in India."

|

|

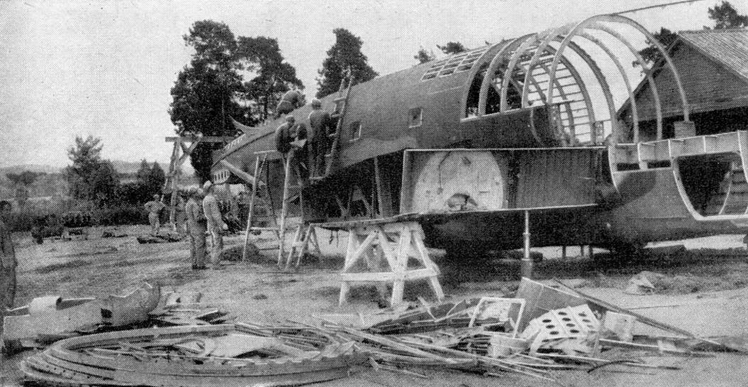

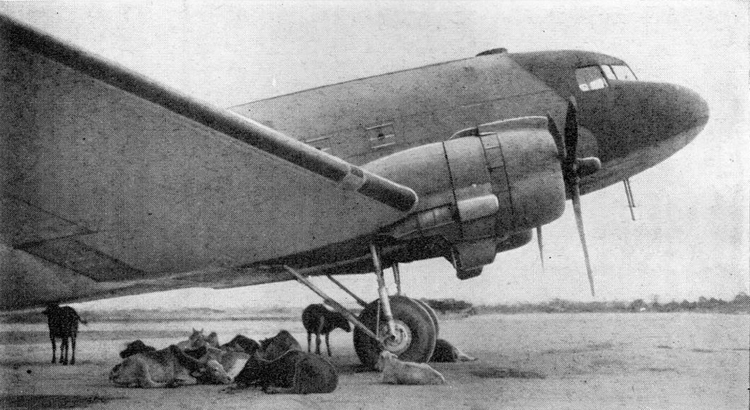

Veterans of the Hump like to tell about the "early days" of the wing which started out with a few dilapidated DC-3's "that no respectable airline in the States would ever let leave the ground." That was in April, 1942.

The men operated from a single-strip airfield constructed by native labor in what had been a tea garden.

"That was some tea party," one pilot reminisced. "We loaded our own planes in those days. Spare parts were as scarce as mechanics. Delicate equipment that goes back to the factory in the States was ripped apart and repaired on the line. Sometimes a line chief would work 72 hours at a stretch."

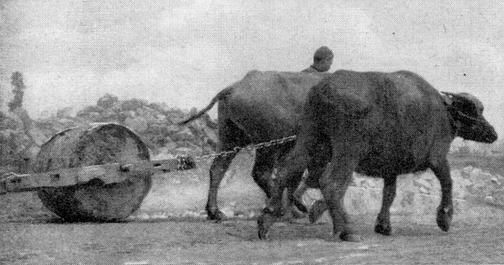

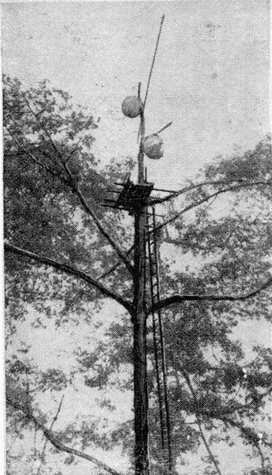

An old radio was rigged up and made to serve as a communications center. There was a shortage of oxygen masks. The old DC-3's were not built for high altitude operations, but that didn't stop them. The pilots did their own navigating with 20-year-old maps and an "array" of instruments that consisted of one compass. Before the planes could take off, water buffaloes and curious natives had to be chased off the field.

Hugging the clouds to avoid Jap planes, flying down valleys to get around lofty peaks they couldn't fly over, fighting unpredictable air currents, ice or fog, this band of men kept a trickle of supplies flowing into China during the dark months of 1942. Later that year the Hump route was turned over to the Air Transport Command and things began to hum.

|

|

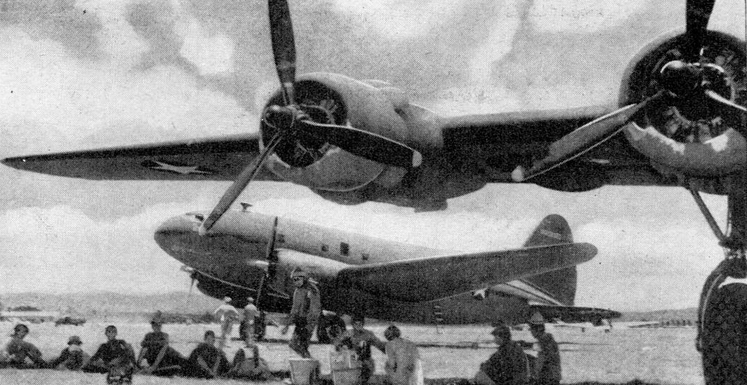

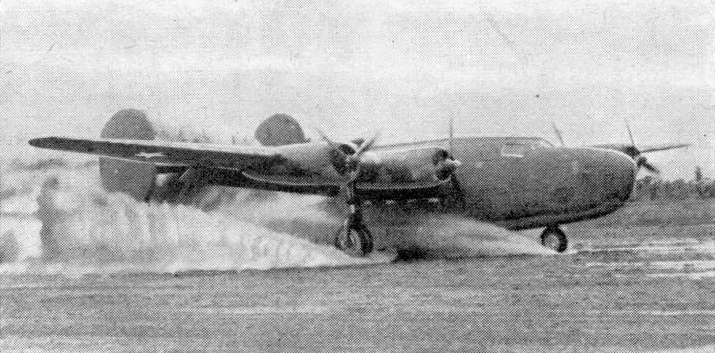

In February, 1943, 2,600 tons of supplies were flown into China. More pilots and better planes were added to the line, including a new Curtiss Commando (C-46). The Commando can carry three jeeps or an equivalent weight of artillery. Then came the freight-carrying Liberators with their 10-ton cargo capacities. Last fall, regular night flying was inaugurated.

Airfield after airfield was hastily constructed. Before the outside world knew what was happening, northeastern Assam had become one of the biggest and busiest air centers. American engineers, pilots and mechanics had accomplished the impossible. By expending a little effort, the Japs could once have taken Assam with its sleepy tea plantations and rice paddies. Now they know it is too late and the best they can do is drop an occasional bomb from great heights and announce to the world "China Wing wiped out."

There is keen competition between the various fields. The men keep a "score board" of the tonnage they carry, and watch it as avidly as they ever watched baseball returns. There is also competition over which unit has the best mess. The pride of one group is an ingenious stove made of two gasoline drums with the ends knocked out. The drums were welded together and set up on supports, leaving room for a grate beneath. Insulation was provided by a mixture of soil and cement. Out of this stove come roasts of buffalo, camel and goat meat to be served alongside wild pineapples, mangoes, carrots, and the dehydrated and canned rations.

|

President Roosevelt paid tribute to the valiant flyers of the Hump early this year with a radioed citation to the entire India-China Wing. The citation, first of its kind to a non-combat outfit, was for "exceptionally outstanding performance in the face of almost insurmountable odds."

Soon the Hump route will be augmented by the new Ledo Road across North Burma which is being built through the jungles by U.S. Army engineers. But until land or sea supply routes are opened up, the men of the India-China Wing will be flying round the clock to keep a brave ally in the fight.

|

FOR PRIVATE NON-COMMERCIAL EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY

TOP OF PAGE ABOUT THIS PAGE SEND COMMENTS

SEE THE ORIGINAL ARTICLE REMEMBERING THE FORGOTTEN THEATER OF WORLD WAR II

Visitors