|

The FISHWRAPPER

By Boyd Sinclair

Former Editor, India-Burma Theater Roundup

'Let Eldridge Have His Paper' said General Stilwell, and CBI Roundup was Born

It was an April day in 1942 at Maymyo, Burma. Near General Stilwell's headquarters, the Baptist Mission hostel, an ex-police reporter huddled in a foxhole. In it with him was Mrs. Clare Boothe Luce. Twenty-seven Jap bombers were dropping bombs across the town. The ex-reporter of The Los Angeles Times, Captain Fred Eldridge, was telling Mrs. Luce about his dream of starting an Armed Forces newspaper in the Far East.

That dream was to be a long time in coming true. The captain was to walk out of Burma with Stilwell before it was realized. Eldridge got out the first Armed Forces newspaper in World War II printed overseas on September 17, 1942. It was the CBI Roundup, later known by GIs over Asia as "The Fishwrapper."

Eldridge hurried and waited a lot before he got out that first edition. There wasn't much time to think about newspapers on the trek out of Burma, and it was summer before Eldridge had time to start

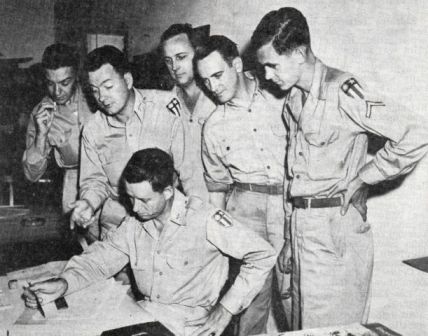

ROUNDUP STAFFERS shown above are (l. to r., standing) Sgt. Charles W. Clark, Maj. Floyd Walter, Editor;

Sgt. John McDowell, T/Sgt. Art Heenan and Pfc. George Gutekunst. Sitting is Boyd Sinclair, Associate Editor.

ROUNDUP STAFFERS shown above are (l. to r., standing) Sgt. Charles W. Clark, Maj. Floyd Walter, Editor;

Sgt. John McDowell, T/Sgt. Art Heenan and Pfc. George Gutekunst. Sitting is Boyd Sinclair, Associate Editor.

|

Eldridge reflected that, as usual, he had asked for a job without preliminary investigation. He had no staff, and newsprint was rationed in India. He had no idea who would print a paper. He first thought about The Statesman, an Indian daily published in New Delhi and Calcutta. The Statesman building was only a few blocks from CBI headquarters. Eldridge walked over. Miss Daphne Tancred ushered him into the presence of James Kewley Cowley, the editor. In 15 minutes Cowley and Eldridge agreed on everything. Cowley even agreed to lend newsprint, subject to replacement from the United States.

Even so, there was still to be a long delay before publication. An officer with authority decided there would be no paper because there was nothing in writing. Stilwell was in China, and Eldridge decided it would be futile to write to him through channels. After two months, Eldridge could stand waiting no longer. He sat down at a broken-down typewriter and hammered out a bleat of 2,000 words to Colonel Dorn. The result was a radiogram from Stilwell.

"Let Eldridge have his paper," it authorized.

All opposition removed, a radiogram went to Washington for newsprint. Time flew by with no answer. Eldridge didn't want to guarantee The Statesman newsprint would be replaced until Washington sent word newsprint was coming. Cowley hinted broadly that American headquarters seemed to be little different from the British GHQ. Eldridge suggested a tracer of the radiogram be sent.

"Be calm, sonny," was the reply. "We'll hear any day now."

Stilwell came to New Delhi while Eldridge was waiting for "any day." He asked Eldridge where his newspaper was. The weak answer brought on language sauced with the well-known vinegar. A tracer to the radiogram was sent. The reply promised newsprint.

Next business was a name for the paper. Eldridge suggested The Asiatic Tiger. This brought only negative head shakes. Stilwell demanded that 20 names be submitted, from which he'd pick one. Brigadier General William Powell's suggestion - CBI Roundup - was accepted. Colonel Dorn suggested the theater shoulder patch be

GENERAL DAN SULTAN presents Legion of Merit to Lt. Col. Fred Eldridge, founder and first editor of the CBI

Roundup.

GENERAL DAN SULTAN presents Legion of Merit to Lt. Col. Fred Eldridge, founder and first editor of the CBI

Roundup.

|

Eldridge, with the help of Francis (Papa) Gomez and Kali Pershad, Indian printers for The Statesman, got out his first issue. He had his troubles with the printers, of course, for printers are basically the same, whether they be Americans, Indians, or Australian bushmen. But he won them over - even the typesetters who couldn't understand the English they set in type. Eldridge had a hard row to hoe for editorial matter, too. He had to write and edit all the copy himself at first. The Office of War Information was his only source of news. Despite trials and tribulations, Eldridge got out the first edition on time. Lt. Col. Sam Moore of the 10th Air Force got the first copy off the press.

The paper flourished a long time under the leadership of Eldridge, and fortunately for its readers; never lost the magic touch of lunacy he gave it. Eldridge created a spirit in the paper that never died. CBI powers finally decided the captain was born for bigger things, and he went on to other duties, finally becoming a colonel.

After he left Roundup, Eldridge kept his hand in the paper's affairs. He sent radiograms and stories from distant points in the CBI weeds. This practice earned him the sobriquet of "The Hand."

The staff of Roundup was never more than three officers and six enlisted men, but the corps of volunteer correspondents ran into the hundreds. Editors ranged in rank from major to sergeant.

Major Floyd (Bucky) Walter, baseball writer of the San Francisco News, served for the longest period as editor. He was known as "Old Buck" and "India's Horace Greeley." He had a nose the marvel of all who saw it. The end had a ruddy, phosphorescent quality and turned up like an indifferent oboe. He was generally regarded by his staff as the most stubborn man in CBI. He was seldom known to confess an error, but he seldom made one. Usually he wouldn't admit misspelling a word, even when confronted with the dictionary.

"That," he would say, when the arguing subordinate brought in the book, "is a Limey dictionary."

Walter, brought up with the San Francisco Seals baseball club, got used to ball players spitting tobacco juice on his shoes early in life. When Darrell Berrigan, war correspondent, spit water through his teeth on Walter's shoes, the editor showed no concern.

"You should see the guys on the Seals," he said. "Berrigan doesn't leave any stains."

Among other editors were Captain Clarence (Clancy) Topp, Technical Sergeant Arthur Heenan, Master Sergeants John C. Devlin and Charles W. Kellogg, and Technical Sergeant Chester S. Holcombe. When Roundup ceased publication on April 11, 1946, a smaller paper called the Chota Roundup was published for the few men left in CBI. Sergeant E. Gartly Jaco was its first and only editor.

Among the many staff members and field correspondents were Captain Luther Davis, Lieutenant Richard McClaughry, Lieutenant Sidney Rose, Master Sergeant Fred Friendly, Technical Sergeant Jack Nolan, Corporal Roger L. Wheeler, Staff Sergeants William Barnum and Edgar Laytha, Sergeant Al Sager, Captain Crosby Maynard, Staff Sergeant Karl Peterson, Sergeant Clarence Gordon, Staff Sergeants Charles W. Clark and Ralph Somerville, Sergeants Wendell Ehret, Michael J. Valenti, and George Gutekunst, Technical Sergeant Edwin Alexander, Staff Sergeants Warren Unna and Jimmie Menutis, Technical Sergeant John Derr, Staff Sergeant John R. McDowell, Technical Sergeant Carl Ritter, Sergeants Ray Howard and Ray Schwartz. Besides staffers and field correspondents,

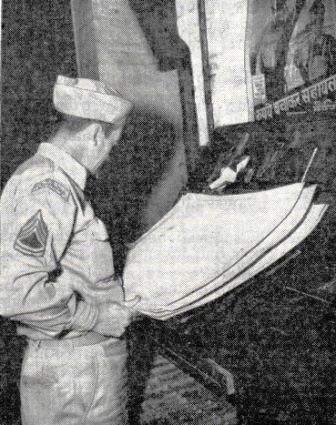

ART HEENAN checks page mats of Roundup at Delhi. Mats are then shipped to Calcutta by plane where

Roundup was printed simultaneously each week.

ART HEENAN checks page mats of Roundup at Delhi. Mats are then shipped to Calcutta by plane where

Roundup was printed simultaneously each week.

|

Sergeant Arthur Heenan, in my opinion, was the best reporter Roundup ever had. He had initiative, skill, and energy. He was a friend of the soldier and talked as plainly and courteously about their welfare to generals as he did to men in the ranks.

One of the most talked-about men on the paper's staff was Sergeant Edgar Laytha, slight, bespectacled New Yorker, born in Hungary. Before he got in the Army, Laytha lived and wrote books and articles of adventure and travel. He flew behind Jap lines in Burma to get stories of the Kachin Rangers. One day in April 1945 he went out with a Ranger patrol. He vanished on a jungle trail near Londaung. When the Rangers withdrew, it was every man for himself. Laytha disappeared on a withdrawal. Did he go the wrong way in the jungle, lose his bearings, and fall into the hands of the Japs?

One story said Laytha, who had a mania for souvenirs and precious stones, went with two Kachin guides to a village three miles from the camp where he was staying. While Laytha was bargaining over stones with the village chief, they were warned that Japs were coming. The two Kachins and Laytha took off for camp on the run. Approaching a brook, Laytha, in the rear, yelled something to the Kachins they couldn't understand. The Kachins motioned Laytha toward camp and plunged into the jungle. When they arrived, Laytha was no longer behind them. No shots were heard. Shortly thereafter, four Office of Strategic Services installations in the area were hit by the Japs. Later a Jap was captured who said he had seen a man of Laytha's description in the company of Jap officers.

Long after Laytha was missing, some men who knew him said they believed he was still alive somewhere in the tangled jungle hills of Burma. But someone always thinks that when a man is missing. The jungles are deep, and those who dwell in them are uncommunicative.

Laytha was sometimes uninhibited in his behavior. His comrades accused him of setting fire to his hair to get attention. He admitted the act but not the purpose.

"I do it to shock little conventional people who take themselves too seriously," he said. "I am amused at the consternation of the inhibited."

The newspaper once told about Laytha's hair-burning act in its columns.

"It looks as if I'm going to have to abandon the hair act," Laytha responded from the jungle. "It doesn't grow out the same way anymore. I am afraid I will have to order from Max Factor a toupee."

Laytha had another act, known as the "flying shoe." This was also to "startle the conventional." Walking besides comrades with one shoe unlaced, he would kick his foot upward, and off would fly the shoe, going 30 or 40 feet in the air.

He impersonated Hitler and sang arias from the great operas in a falsetto soprano. In the Hitler act, he shrieked in frantic German for a glass of water.

"That's the same way he does when he asks for England," he said.

Laytha had various romantic names for himself and other people. He called himself "The Knight Errand of Roundup," and just before he made his last jump into the jungle, he referred to himself as "Lord Parachute." He used to refer to me in his jungle letters as "The Prince of Kweilin" and addressed Sergeant Heenan as "The Irish Baron of Davico's." Davico's was a New Delhi restaurant and bar. The salutation in his Heenan letters was always "My dear Irish baron and friend." He usually denounced Heenan for the way he cut his dispatches. He referred to the editing process as "hee-nanization."

"When a story with a soul gets on Dr. Heenan's operating table, the patient rarely recovers," he wrote in a jungle letter.

Laytha, like Eldridge, sent long radiograms from far away. He made corrections by radio on copy previously mailed in. The gem of all these was a radio message from Myitkyina.

"Virginal character of Burmese girl in aviation story which Eldridge took to Delhi should be killed, says Laytha. Checkup proved three abortions. Both she and 14-year-old sister are carrying on with Americans. Leave them in story as lush Burma belles."

As the story already had gone to press, these ladies are still virgins to the whole wide world, definitely a kinder treatment, if not quite accurate.

Laytha had a Jap uniform he planned to test the Calcutta MPs with when he came out of the jungle. He intended to put on the uniform, complete with Samurai sword, and stroll down Chowringhee Road, he said. He made bets the MPs wouldn't arrest him. If he got away with it, he planned to call on General Neyland and point out to him the shortcomings of his GI cops.

Probably the funniest man to work on Roundup was Sergeant Charles W. Clark. Clark's morale was usually so bad he made everyone else's good. The choleric sergeant had no love for India. He wanted to go home and adopted as his personal motto, "Let's quit India." Because that was out of the question, he became known around New Delhi as "T/S" Clark. Clark's gum-beating inspired a fellow staffer to write a parody of "Tit-Willow."

A sergeant quite sour sat on Headquarters fence,

Griping, "India, oh, India, quit India."

He hardly would stop till again he'd commence,

Bitching, "India, oh, India, quit India."

He moaned, "Let me tell you - my words I'll condense -

The general idea is, just let us get hence.

"Quit India, quit India, quit India."

Clark heard now and then from a girl friend in Fort Worth, Texas, he called the Pink-Eared Blonde. After a time, reports reached New Delhi that the Pink Ear had wed.

"Men, I've had it," Clark commented as he displayed clippings from a society section.

Clark was questioned about the man the Pink Ear had taken on as a companion through life.

"I forget his name," said Clark, "but rest assured he was a local 4-F who made a pot of money selling defective out baskets to the Army."

Clark thought the situation could be eased by a visit to Davico's for a "rum cup." A second visit, he believed, would remedy the situation for good.

In contrast to Clark was Staff Sergeant Karl Peterson, who achieved the same results -

CLARK (at typewriter) impersonates busy officer. Heenan holds an MP club. Major Walter (with campaign hat) and

McDowell (right) look on. Don't ask what they are doing. Roundup office at Delhi had the reputation of being

a madhouse!

CLARK (at typewriter) impersonates busy officer. Heenan holds an MP club. Major Walter (with campaign hat) and

McDowell (right) look on. Don't ask what they are doing. Roundup office at Delhi had the reputation of being

a madhouse!

|

"Our new home, in the corncrib class," he wrote, "proved to be a deserted second-floor sleeping bay. Roundup was installed next to a latrine, in which maybe there is some logic. A glance out the windows of the new home proved that adjacent bays were still used to quarter troops. Blinders have been requested for females who sometimes come to see us. Their modesty must be considered around the office if not in the paper."

Roundup staffers traveled thousands of miles for stories and to cover special events. The longest trip made was by a soldier who usually stayed the closest to home base in New Delhi. Technical Sergeant John Derr, longtime sports editor, flew from New Delhi to St. Louis in 1944 to cover the Cardinal - Browns World Series for CBI's baseball fans. His was the longest trip ever made to cover the World Series.

War correspondents at times wrote for Roundup, but none was as close to the staff as Darrell Berrigan. Berrigan, born in Yakima, Washington, described himself as "a worm from the apple country." He called himself Honorary Sergeant (Captain - if - captured) Darrell Berrigan. He was an old CBI wallah, having walked out of Burma with Stilwell. He was the first man I ever heard say CBI stood for "confusion beyond imagination."

Berrigan was probably the most hospitable man to soldiers in Asia. His apartment at 9 Wenger Flats in New Delhi was often jammed with Air Corps characters, jungle jollies, old China hands, and rear echelon commandos. He often didn't know whether he had a bed to sleep in or not. One soldier, instead of going to rest camp, spent his vacation with Berrigan. Berrigan got himself a rubber mattress and hid it so he would have somewhere to sleep if he came home late and found a GI in his bed.

Roundup's cartoonists and artists contributed as much to GI acceptance as writers and editors did. The first staff artist was Technical Sergeant Jack Nolan of Brooklyn. His puckish character, "Corporal Gee-Eye," later earned him a decoration. Staff Sergeant Ralph J. Somerville followed Nolan. The former movie cartoonist looked like a tired d'Artagnan and had the aplomb of a French country squire. Nothing ruffled Somerville except old animated cartoons at New Delhi theaters. Some of them he'd worked on 10 years before.

"I'm always paying to see my own stuff," he complained. "If history repeats itself, I'll be buying copies of Roundup in 1955."

Roundup's gentleman cartoonist was Technician Fourth Grade Wendell Ehret, known as "The Sheriff" to his buddies. His Strictly GI often had a sense of the ridiculous and again was pungent or tinged with pathos. One of his best-remembered cartoons depicted an MP lieutenant giving a private first class a lecture for an improperly buttoned shirt. The lieutenant had sprouted feathers on his head, posterior, and arms, and the caption read: "Let's get that button buttoned up, soldier, if you don't want to lose that stripe. Cackle, cackle, cackle."

Ehret was probably the only soldier in World War II to get his letters to his girl friend published in book form. The letters were cartoons, with a little use of the alphabet here and there. The book was published by Robert McBride in New York under the title of "Dear Gertrood."

Ehret was such a modest, gentlemanly fellow that one day a Roundup staffer asked him why he became an artist. The staffer had been used to the screwball type who grimaces in mirrors to capture desired expressions. Ehret confounded him with his reply.

"I was brought up on a Colorado ranch," he said. "I know how to do two things - milk cows and draw. I decided to take up the brush instead of the udder as a life's work."

Roundup's editors tried to make the paper a friend of the soldier. It found shoes for soldiers whose feet were big and influenced Congress to pass a law so GIs could send souvenirs home free of import duty. Roundup even got a flag for one outfit which wasn't able to get it through channels. The first GI for whom the paper got shoes was Technician Fourth Grade Paul W. Crow, who wore size 14½-A. Channels didn't function for Crow, so the newspaper took the problem to General Covell, Services of Supply chief. Crow got shoes and a personal letter from the general, who had an explanation.

"Finding these shoes was no easy job, for they had been stored away with objects of similar size - engineer bridge pontoons."

Supply also failed to function for Private First Class Richard Sloan of the 48th Air Depot Group.

"I want to make an appeal for shoes," he wrote the editor. "Seven months ago I turned in a pair, and they sent to Calcutta to see about some. My only pair has been repaired so many times they can't be fixed anymore. They're falling apart. When I walk I can feel the mud between my toes. My size is 11½-AA. Malum, sahib? No shoes. Please - you guys help me."

The letter was taken to Major C. C. Dilatush, executive officer for the CBI Quartermaster. Dilatush found the shoes and shipped them, all in one day. He sent Sloan's commanding officer a radiogram, informing him Sloan's shoes were on the way. To top things off, he wrote Sloan a letter, expressing the Army's regrets.

One of Roundup's first editorial complaints was about an unsanitary mess hall for transients in the forward areas. This got results. Another was the campaign criticizing obvious absurdities in the censoring of soldiers' mail. The paper did not oppose official censorship, but local ground rules without official basis.

Roundup's attempts to be a friend to the soldier were not wise in some instances because of errors in human judgment and because its editors sometimes started off half-cocked. Being a friend to the man in the ranks was about the only serious policy the paper had. The only other policy of any kind ever mentioned was in the words of Eldridge, the first editor. Another officer asked him what the paper's policy was.

"Hot pants and laughs," Eldridge replied.

The paper, of course, was censored. It usually got along well with press censors, and went so far as to suggest that proofs of all type be censored. When censorship appeared to be the result of muddled thinking, or erroneous application of regulations, Roundup protested.

The day after President Roosevelt's death, Roundup decided GI comment on the

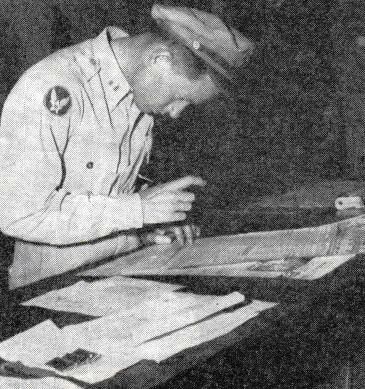

Capt. BOYD SINCLAIR, one of Roundup's many editors, is shown here checking page proof in composing room

of The Statesman in New Delhi.

Capt. BOYD SINCLAIR, one of Roundup's many editors, is shown here checking page proof in composing room

of The Statesman in New Delhi.

|

The press censor blue-penciled all soldier quotes that in any way voiced concern about the future of the United States at the peace table. When the editor asked the censor his reasons, the censor said he had done so on the basis of the Articles of War. The editor asked him which articles served as the basis of his decision, and he replied that Article 62 was pertinent.

The editor, returning to his office, wrote his immediate superior, Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Sill, Jr., sending him a galley proof of the censored story.

"Basis for this censorship," he wrote, "is that portions of the article marked for deletion are in violation of the Article of War dealing with disrespect for the President and other national and state officials.

The letter quoted Article of War 62.

"Any officer who uses contemptuous or disrespectful words against the President . . . shall be dismissed from the service or suffer such other punishment as a court-martial may direct. Any other person subject to military law who so offends shall be punished as a court-martial may direct."

The letter, after quoting the article, continued.

"It is respectfully requested that specific attention be given to the phrase, 'contemptuous or disrespectful words,' in the above-quoted article.

"It is the firm belief of the undersigned that not one single soldier quoted, or Roundup, has said or inferred any contempt or disrespect for President Truman, or anyone else. Rather, it is believed that President Truman is shown to have the respect and loyalty of our troops.

"The undersigned believes," the letter concluded, "that if this article is not passed for publication, the soldiers quoted and the soldier readers of this newspaper will have been done a serious wrong. If the Information and Education Officer concurs, it is requested this matter be forwarded to the theater commander, if necessary, for a decision."

Next day the blue-penciled copy was brought to Roundup's office with the rubber-stamped notation, "Passed for publication."

Roundup didn't always win the decision. If it didn't, it played the part of any good soldier, accepted it, and continued with its duty. The paper prepared an article critical of the British because they were critical of the movie, "Objective, Burma!" The British said the film was American propaganda and Americans were trying to leave the thought with film audiences that the United States alone won the war in Burma. Roundup didn't believe British critics had good grounds for their assumptions.

Objection to the article was raised because it would "sow discord and discontent." Major General Vernon Evans, chief-of-staff, upheld the objection.

"Let's lay off who won the war in Burma," he wrote on a buck slip. "It was generally agreed in the last war that the MPs won it. Thereafter, people lived in peace without argument. Maybe the MPs have done it again."

As General Stilwell said, Roundup served as a safety valve for CBI men. Letters

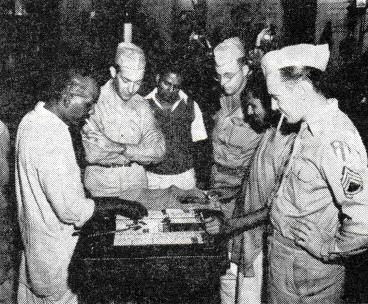

MAKING UP pages of Roundup in composing room of The Statesman in New Delhi are (l. to r.)

Kali Pershad, Indian employee of The Statesman, Sgt. Clark, Indian Linotypist, McDowell, Indian printer, and Heenan.

MAKING UP pages of Roundup in composing room of The Statesman in New Delhi are (l. to r.)

Kali Pershad, Indian employee of The Statesman, Sgt. Clark, Indian Linotypist, McDowell, Indian printer, and Heenan.

|

"Roundup's weekly columns served as a sounding board for the views of its readers and as a means of spotlighting inequalities," he said.

Next to letters, poems were second in volume. The muse touched private and colonel alike, poems usually ranging from verse to worse. Little of it could be classed as literature.

Sergeant Smith Dawless was the paper's favorite poet and Private Rastus Corley was its most prolific. Private Corley sent in more than 200 poems. As an award for his devotion to the pen, the poetry editor decided to print a verse with Corley's picture.

"This is just as great as if I was about to become a father," Corley wrote when he sent his photograph.

GIs constantly mailed money for "extra" copies of the paper. One GI said his first sergeant was stealing half his outfit's copies and sending them to his relatives. When soldiers were told the paper could not be bought, many offered to buy stamps to cover cost of mailing. Many people in the Orient outside U. S. forces offered to pay to get on the mailing list.

The paper was distributed one copy for two men. Circulation at its peak was around 140,000 to 150,000 copies an issue. Roundup probably had the widest area of general circulation of any newspaper ever printed, and no doubt had the biggest circulation of any English-language newspaper ever published in Asia.

The FISHWRAPPER

Story from the July 1952 edition of Ex-CBI Roundup shared by CBI Historian Gary Goldblatt.

Copyright © 2007 Carl Warren Weidenburner

TOP OF PAGE PRINT THIS PAGE SEND COMMENTS ROUNDUP HOME PAGE