Scroll down to view...

Mail call comes only once a month, there's never any pay day and the jungle is a worse enemy than the Jap. NORTHERN BURMA - One day during the fall of 1942 a clerk at Services of Supply Headquarters in India was studying a requisition form from a Signal Corps Aircraft Warning outfit. After reading the form again he suspected that someone was trying to pull a gag. The clerk called a sergeant. Then the sergeant called a lieutenant. "Now, what the hell do they want with that kind of stuff?" asked the sergeant. "Colored beads, rock salt, flashy-colored blankets and - well, and all those other crazy items." Today SOS Headquarters in this theater is no longer surprised at anything that Aircraft Warning may order. Requests for items that aren't strictly GI are complied with quickly and without question. To accomplish their mission, men of the Aircraft Warning units frequently have to venture into strange and unexplored sections of the jungle. They are often forced to call for the help of natives who have never seen white men before, and these natives usually prefer glittering and flashy objects to money. During its history, Aircraft Warning has constructed hundreds of miles of jungle and foot trails, and many times, because of the nature of the terrain, its men have had to travel far beyond Jap lines to establish their stations. The first station was established late in 1942 in the Naga Hills of India, on the Burma border. Later, as the Americans and Chinese fought their way through northern Burma, many other stations were set up in the jungles and hills of that country. Now the network is so vast that a Jap plane can rarely sneak over our lines without being detected. The station I visited is only a few miles from a road on the Burma-India border. Many other stations, however, are so far back in the jungles that it takes anywhere from 5 to 18 days' walking to get to them. The trails are narrow and

Our guide was T/Sgt. Fred Fegley of Pine Grove, Pa., a former lineman for the Pennsylvania Light and Power Company. Fegley has spent more than two years at various stations and during that time he figures he has hiked upward of 1,500 miles of jungle trail. "I'm not kicking, mind you," Fegley said as we paused for a rest. "But back in the States nobody in our outfit ever dreamed we would go through anything like this." Fegley said that the outfit's greatest danger was not from the Japs, but from nature. During monsoon seasons the men don't dare sit on the ground for a rest. "You even pick up leeches when you're walking," Fegley said. "Frequently you have to stop to pick them from your body so they won't suck too much blood out of you." And during the monsoons, streams become rivers. There are dozens of streams across the paths to many of our stations. So a station that takes a five-day hike in ordinary times is difficult to get to in twice that time when the monsoons are on." One thing you can knock off as a myth, according to Fegley, is the danger from wild animals such as tigers and elephants. "Actually our outfit has had little trouble from animals," Fegley said. "Most people like to exaggerate the number of wild animals they see in the jungle. Of course, you do have to be careful. Once one of our men put up his jungle hammock for the night and his dog crept under it to sleep. Next morning there was a pool of blood but no dog." The average station is operated by a 10-man team with a staff sergeant in command. The men are required to spend at least six months in the jungle before returning to a rear area for a rest. But oftener than they like, they have to remain longer. Some teams have served at their posts as long as 11 months without relief. One of the first acts of an Aircraft Warning team is to call on the village nearest the station. Most natives have been helpful; they've shown the men where to find their water supply and helped them build bashas - quarters for the men - from bamboo and thatching. The Army's system of going through channels is found even among the natives in the jungle. Before hiring anyone the men first contact the headman of the village, who then designates a number of his people to work at the station. The headman usually sends his own son to act as a sort of straw boss.

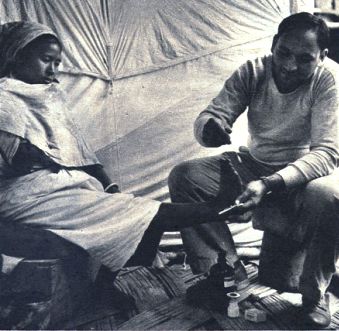

"Things have changed from the early days in these jungles," Fegley lamented. "It used to be we could do a flourishing business with the natives by trading large tin cans. One can would bring you as much as a chicken. Now there are so many tin cans that it's caused inflation. A guy cant' even get the shell of an egg for one." At one station where the men ran out of trinkets, a GI squeezed all the cream from a Williams shaving tube. Then he very neatly flattened the tube and gave it to one of the natives. The native wore it as an ornament around his neck - free advertising for Williams shaving cream. Medics are highly respected by the natives. Sgt. Eugene Schultz of Buffalo, N.Y., is the medic at the station I visited. All the natives there call him Doc. "We're too far from a village here," Schultz said, "but at other stations some of our medics make weekly calls on the villages. On visiting day every woman and child groups around Doc, and they all pour out their troubles. "One thing we have been able to accomplish in these jungles is to teach these people to be cleaner. Many of them suffer from malaria and dysentery. Since we've been stressing cleanliness we've found fewer of them with dysentery." During my stay at Schultz's station, a native woman came in with a badly infected foot. Schultz tried for days to persuade her to soak it in hot water and epsom salts. She finally consented after other natives nagged her into it. "Usually you don't have to urge them," Schultz says. "And, brother, once you get them coming to sick call you really get the business. They come whether they're sick or not. When you give one of them a pill they all demand one. We finally got around it by giving salt tablets to those who weren't ill. The salt tablets do no harm and they make the natives happier." The days at the station are long and boring. Some of the men have taken to writing books and short stories. Occasionally the headman invites one of the GIs to a pig roast in the village, but mostly the men spend their time reading or hunting. Every team is given a 12-gauge gun for hunting purposes. Barking deer, pheasants, quail and several species of grouse are the most common game.

Some of the men have taken to teaching the children to read and write, and many natives around the stations have acquired an elementary knowledge of English. Cpl. Russell Higgerson of Albany, N.Y., was teaching two children at the station I visited. "Don't kid yourself about their appearance," Higgerson said. "These kids are as smart as any I've seen back home. I'd love to take one to the States and see what a school education could do for him." Mail service is the biggest gripe the men have. Mail, delivered with food and supplies, is dropped by C-47s once a month except during the monsoon season, when it's even slower. The problem of getting mail for the States out to an APO is more difficult. At some stations the men have worked out a runner system with native messengers. But the men at stations 50 miles or deeper in the jungle have to wait many months before they can send a letter home. To keep their families informed, the officers at headquarters write for the men. The men aren't paid until they report back to headquarters for a rest, but since there is no place to spend money, they don't give the pay delay a thought. Some men in the outfit have had their share of combat. When Col. Philip Cochran and his 1st Airborne Commandos landed 150 miles behind Jap lines in northern Burma in March 1944, an Aircraft Warning unit went along. Most of their equipment was bombed out after the men had landed, and many of the men suffered from malaria. Nevertheless they went on with their work and established a station. Last April, when the Japs penetrated into Assam in their threat to invade India, the men in the Kohima district remained at their stations until the enemy almost overran them. 1st Sgt. Daniel H. Schroeder of Casnovia, Mich., a communications chief, was one of the last American enlisted men to leave his post when the Japs cut the Manipur Road between Kohima and Dimapur. And during the Jap drive, Aircraft Warning units were the sole medium of communicating intelligence to the British. Native scouts reported the Jap movements, and the men at the stations relayed the information to the British. Fegley was team chief at one of those stations. At 2200 one night, a native reported that the enemy had infiltrated the area near the station. Fegley ordered his men to destroy all equipment. He also ordered that all food cans be broken with axes and creosote poured into them. This was done so that the Japs, who were known to be short on food, could not benefit from our supplies.

At 0300 next morning, Fegley and his men took their field equipment, tommy guns and hand grenades and began hiking through the jungles to warn another station. The men walked until 2200 that night, covering a distance of 28 miles. After taking a five-hour break, they resumed the trek until they reached the other station, 19 miles farther. The threat of Jap planes has been eliminated to a great extent in this theater, but the men are still kept busy. These hills are among the most difficult in the world to fly over, and a number of crashes result. When this happens, the stations nearest the crash are called upon to send out searching parties. Dozens of flyers have been saved in this manner. In August 1943, when John B. Davies, secretary to the American Embassy in Chungking, crashed with a number of American civilians and soldiers and Chinese officers, men of Aircraft Warning went to the rescue. The plane crashed in the Ponyo area of the Naga Hills. Some natives in that area are known to be head-hunters and generally unfriendly. Therefore help had to be sent as quickly as possible. Two Aircraft Warning men - 1st Lt. Andrew La Bonte of Lawrence, Mass., and S/Sgt. John L. DeChaine of Oakland, Calif. - together with a British political officer, organized a searching party of natives acquainted with that section. The men tramped over narrow paths and through mud and water for five days and covered 125 miles before they found the crash victims. When the party prepared to leave with 20 survivors of the crash, some natives started a riot over items that were left behind. Sgt. DeChaine, employing a little Yankee diplomacy, intervened and quelled the riot. "In this business you've got to be a diplomat, a businessman, a hermit and an aircraft observer," Fegley said. "Mostly, though, you've got to be ready for surprises. Anything can happen here, even if we are a bunch of GI jungle orphans."

|

|

A vital phase of China's war against the Jap was connected with our trip and with other trips like it. The millions were to be delivered to a group of GIs in Tibet and in the unexplored part of China inhabited by the Lolos - fierce, black-caped characters who consider it sport to rob and kill. Our party was bound for Lololand, armed with two shotguns, two .45s and an M1, but we would have felt better with a brace of machine guns. That much cash makes you nervous. The Lolos and the Tibetans have good horses and the GIs at our destination were there to buy them for China. China needs horses in girding herself for a squeeze-ply against the Japs as the possibility of an invasion of China's eastern coast grows stronger. One look at China from a plane will answer any questions about the need for horses. There are only a few roads good enough to handle the weight of trucks to carry supplies to the fighting fronts, especially if these fronts should mover farther east. The only feasible way to get supplies through is to pack them by horse. Horse trading was our military assignment. Out of Kunming, we swung onto the newly opened Burma Road. We stuck to it for three hours and then turned off to head straight north. The U.S. Army convoy trucks we left behind us on the Burma Road were the last American vehicles we were to see for over a month except for another weapons carrier and a jeep that were in use by GIs at the horse-trading encampment. We had three days of roller-coaster riding before we sighted the very blue waters of the Yellow River. Part of the Chinese Navy - we had never thought of a Navy so far inland - ferried us across. After that, more road, this time dotted with flimsy wooden bridges. Many of the bridges bore scars of fire and we knew we were nearing the Lolo country. We had heard that some of the Lolos had been on a rampage not long before and had burned down a number of bridges so that they could waylay any vehicle held up by one of them. The Chinese Navy had told us that two bridges were down, but that new ones were near completion. Their G-2 was correct for we found all finished bridges and were reassured at evidence that communications were better than we had thought. All that money in these surroundings still worried us. When we pulled into a small town to stay overnight our relief was almost audible.

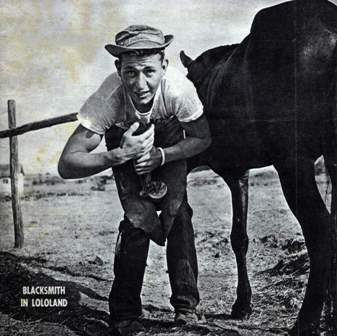

Sgt. Willard Selph, of the veterinary outfit which does the horse buying, parked the weapons carrier and we unloaded our stuff in a building erroneously called a hotel. Upstairs it boasted bare rooms, littered with egg shells that must have been there for weeks. Light came into the rooms from rat holes large enough to accommodate a small, foolhardy dog. The windows were paper-covered holes in the wall. This was the only available lodging in the town, so we parked our gear and our millions and left Maj. Earl Ritter to guard it while we hunted up a recommended restaurant. We walked through dark, narrow streets and halfway to the eating place in this blackness came upon a sight that dashed my appetite to bits. Hanging just above our eye-level were eight human heads, strung up on a cord between two poles. Wong, our interpreter, evidently wanted us to get the full effect for he said nothing until after we had seen them. Then he told us the story: They were the heads of savage Lolos brought back by friendly Lolos as prizes of war from a battle of the week before. He further explained that "white" and "black" Lolos war periodically because of crimes committed by the latter. We thanked him. We pulled out the next day when the town was having its annual Buddha-washing festival. The citizens wash the statue on a certain day every year and the cleaning is done by a selected man and woman, the "living Buddhas." The lucky couple is carried up to the statues in a long procession and they bring everything with them in the way of oil and trinkets except soap. We found half the men on the horse-buying assignment, when we arrived at the camp, considering their job in the light of a rest camp deal. These are GIs who have been through the misery of the Salween campaign which helped reopen the Ledo-Burma Road. Even this out-of-the-way spot looks good to them now. The GI who looked and talked more like a cowboy than anyone else at the camp was T-4 Michael Brutcher of Wilkinsburg, Pa. He was a steel worker there, but when he shipped to this theater he was put into a veterinary outfit; why he doesn't know himself. Brutcher had belonged to the outfit that was rounding up, buying and delivering horses to Ledo for use by Merrill's Marauders. He was doing the same job when we saw him. Two westerners in the detachment - Pfc. William Hightower of Stephenville, Tex., and Pvt. William Nealon of Denver, Colo. - have the toughest job in the whole assignment. They are the pack leaders and, when the desired number of horses are bought in the area, Hightower and Nealon with a string of Chinese mafus (caretakers) lead them to a collecting point somewhere in southern China. When the time comes for shoeing the herd before it heads south the job will fall to T-4 Norman Skala, a GI blacksmith from Elgin, Ill. The crux of the job - buying the horses - is not so simple a matter as dipping into the millions of dollars and waving a fistful of cash before the eyes of the horse owners. Horses and guns are the most highly prized possessions

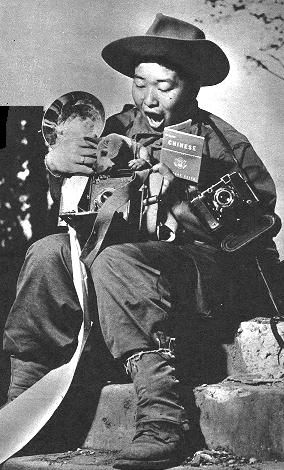

The first step in buying is for the GI traders to go into a town and get in touch with a magistrate, for a magistrate in this country has power of life or death over his people. They ask him to spread word that Americans are in the city to buy whatever horses are for sale. The owners then bring their horses into town and they bring with them a mayadza, a professional horse broker. All deals are made through the mayadza, never directly with the owners, although the owners are present most of the time to keep an eye on the progress of the trading. If the bargaining is successful, the broker shouts, "Maila!" to the owner. This means "Sell!" If the owner agrees, the mayadza drops the halter on the horse and the deal is closed. You don't own a horse until the moment the broker lets loose the halter. Both brokers and owners drive a hard bargain. Maj. Charles Ebertz of Auburn, N.Y., who has done most of the buying here, a practicing vet in civilian life, reports case after case where he spent three to four hours buying one horse. Occasionally, sellers will pull fast ones. Once a GI buyer discovered too late that he had paid a good price for a club-footed horse. During the sale the animal had been standing ankle-deep in straw. In some instances money is no good at all. Almost all the Lolos would rather have silver blocks than folding stuff and that poses another problem for the GIs, who have to go out and hunt up sufficient silver blocks. Tibetans, on the other hand, will take money if they have to but prefer barter goods and the things they ask for have caused many an issue head to be scratched. They are moved by fads and the last Tibetan fancy was for yellow felt hats. For such a hat a horse owner in Tibet would trade his best nag. Col. Daniel H. Mallan of Harrisburg, Pa., head of all the horse-buying groups, made a special plane trip to China and back to procure yellow hats. He couldn't get any felt ones, but yellow-painted helmet liners came close enough to buy a few horses before the fad melted away. A trip we made with one of the trading parties will give a rough idea of typical horse procurement routine as practiced by the Army in China. We drove first as far as we could by motor to a small town to which our saddle horses and mules had been driven the day before. Their arrival had spread the word of our mission before us. When we arrived at the town at 0900 there were crowds of curious spectators who had been waiting for us for hours. They mobbed our truck by the hundreds and helped us saddle our horses and load our gear. Just as we were ready to shove off, half a dozen of them grabbed us by the arms and led us to a hovel that looked like a Hollywood opium den. There they brought out a huge black jug and poured each of us a bowl of their very best rice wine, stored away for special occasions like this. It was like liquid dynamite, but, as soon as we took a sip from our individual bowls, our hosts refilled them. Dish after dish of food followed the wine and the meal was interrupted constantly by toasts. As soon as we finished one meal, another party was on hand, dragging us to its hovel. Everyone wanted to entertain. Everyone who had a delicacy on his own dish wanted us to take a bite. Two hours went by before we could get our show on the road. We reached the Lolo village we were seeking late in the evening and, although we were dog tired, our eyes opened at the sights that greeted us. We had heard earlier that there was a sickness among the Lolos and in the village we saw four tribesmen stretched on the ground in the last stages of something. It wasn't until the second day that we found out the nature of the plague. The four had been having a party on rice wine 10 times stronger than that we had sampled down the road and were recovering from the inevitable attack of DTs. The youngest son of the tribal chief, Lo-Tai-Ing, came out to greet us. He bowed gracefully and in very good English repeated that favorite GI expression about "blowing it out." That was all he could say in English and it reminded us of the story that a bomber had crashed up country and its crew had never been heard of. We were nervous again. Wong immediately announced the reason for our visit. He told the Lolos that we had silver to buy horses and that we came bearing gifts and medicine. The tribesmen tied our horses and took us to a room in the mansion of the chief. In a matter of minutes we were backed up against the wall by a stream of Lolos who pushed into the room to get a look at the Meigwas - the Americans. They stared at us, checking their own features against ours, and mumbled among themselves. They felt the texture of our skins and measured our wrists, ankles and necks. Then they took turns standing beside us to compare heights. They were amazed by our wrist watches and pocket knives, but our guns were the main attraction. After they had concluded the inspection to their satisfaction, some of them took Wong aside and told him they would like to have a shooting contest with us. Maj. Ebertz agreed and said he would stack his M1 against any of their rifles.

We slept in the Lolo village that night and in the morning the chief's son came to Wong with word that the tribesmen were going to kill two bulls in our honor and did we want to watch the slaughtering? The Lolo method of killing animals isn't pretty and we didn't stay out the whole show. What we did see was enough. One Lolo felled the first bull with an axe and, as it wavered to its knees, he pounded over the heart, on the back and on the legs, screaming every time he swung the axe. The Lolo onlookers hopped up and down, delirious with laughter. While the bull was still kicking, a second Lolo slit its throat. We were supposed to accept this sacrifice with deep appreciation. The killer's axe missed its target on the second bull and the animal got away to the hills, at a fast pace. The Lolos gestured excitedly to the major that they wanted him to shoot the runaway. He brought it down with a single shot, the cleanest execution in Lololand in a long time. We checked out before the final details of butchery. That evening the Lolos feasted on the two bulls. They sat in circles, about 20 to the circle, eating the beef from massive bowls, one to each group. They had only one eating tool, a spoon which looks something like a tiny niblick. It is used for their soup which is served at every meal and one spoon does for a whole circle of diners. Their eating must rank among the world's nosiest. With some 200 lips smacking in enjoyment at one time, it sounded as if you were standing near a lake listening to the slap of waves against a row of moored boats. They did not invite us to join any of the circles and we did not regret it. They did bring us some uncooked liver and tripe to take back to camp with us. Our quarters while we were with the tribes were in the corner of a large room on the second floor of the chief's mansion. The house is still abuilding and Wong discovered that this marked its fourth year of construction. The Lolos themselves know nothing about carpentry and such work is done by Chinese they have captured and enslaved. Farming, too, is a slave's job, and the Lolo warriors are left with little to do but drink rice wine all day. After the bull feast, the chief paid a visit to our quarters. A bearer brought a large kettle of rice wine and placed it at the chief's feet. We had to drink because the major planned to make a token purchase of a few horses. It was a quick deal, for its one purpose was to impress the Lolos that we were in the market for horses. Even before the deal was closed curious Lolos began to jam the room. The squatted against the walls and watched us as the chief had a second meal after selling the horses. The chief ate with chopsticks this time and we shared some beef and pork with him. The smell of bodies in the room was stifling. The tribesmen squatted close to us, constantly feeling our muscles, touching our faces and rubbing the hair on our arms. Their faces were strange and distorted in the candlelight. They took the jungle knives out of our belts and seemed content to sit and hold and stare at them. They inspected every single item of our clothing. The zippers on our field jackets were something they couldn't believe. When we smoked they were not so much attracted by our cigarettes as by the matches we used to light them. They light their own pipes with flint and metal. When Wong informed the chief that we had to leave in a few days, he tried to persuade us to stay longer. He wanted us to remain in the village long enough to teach his people some American habits and maybe a few words of English.

The Lolos themselves are not yet certain that the world is round. They asked us for proof that the globe spins. If it spins, they reason, why don't people fall off and why doesn't the water spill out of rivers and lakes? They believe that the chief's house, a three-story structure, is the last word in modern building. When we told them about skyscrapers and New York, they refused to believe us. The chief's right hand man told us that the Lolos had seen a few airplanes. If the Americans could make such things from reading books, he said, then the Lolos were going to get books. The chief's brother, considered the most daring man in the tribe, offered the major his best horse and the title of godfather to his children, if he could have a plane ride. The major said he would try to arrange it. We sensed something more than curiosity in the brother's request. It seemed possible that he was preparing to unseat his brother and was banking on adding to his personal prestige in the community by taking the death-defying risk of air travel. The evening's Lolo version of a bull session finally folded and we slept. The rest of our stay with the tribe was largely a matter of preparing to leave for camp. The Lolos continued in their curiosity about us and we continued to observe them. The Lolo women, we discovered, are attractive - what you can see of them. Only their hands and faces, and sometimes their feet, are visible. They seem quite innocent of bathing and the dirt on their hands has undoubtedly been untouched by water for years. Possibly they observe the Tibetan custom of but three baths per lifetime - one at birth, once at marriage and finally at death. This allergy to bathing was a major obstacle to our interest in the Lolos. We could observe them with enthusiasm while our lungs were full of fresh air, but enthusiasm waned with longer, closer contact. Our mission had been finished with the buying of the horses. We packed our gear, including our kidney and tripe, mounted our horses and headed back to the GI camp.

|

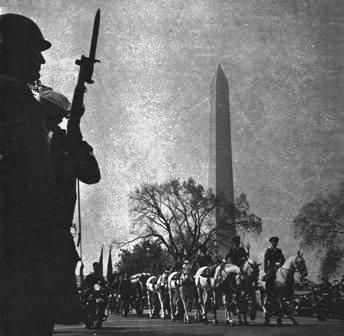

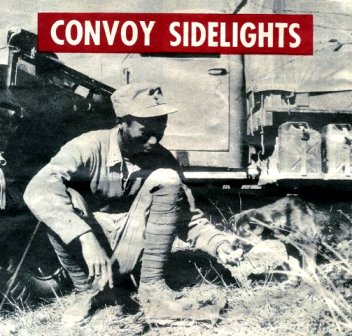

When I started from Myitkyina, Burma, in Green's jeep, he had muttered: "To me this is just another dirty detail. Damned if I don't always seem to catch 'em." All through the trip he had stuck by that belief. "Who likes sleepin' on the ground?" he would ask. "Or cooking his own meals? Or getting windburned and chapped and covered with dust? I sure as hell don't." Then, on Green's birthday, our jeep finally swung through the narrow streets of war-swollen Kunming at the end of the thousand-mile journey, and Oscar took in the scene. There were thousands of Chinese - some wrinkled with age and some tiny kids, a few of the wealthy in fine clothes and an overwhelming number of poor in tattered rags. They lined our path for miles, scanning the long procession of vehicles, waving banners, shooting off firecrackers, grinning, clapping and shouting. Green dropped his cockiness and cynicism. He grew silent. When he spoke again he was dead serious. "You know," he admitted grudgingly, "you been hearing me bitch ever since we started, but now that it's all over I guess I was wrong in a way. I'm sorta glad now we made the trip because somehow I feel this thing's gonna go down in history." Most of the rest of us in the convoy went through the same transformation as Oscar Green. Those of us who realized early the significance of what we were doing were backward about saying so, afraid of being laughed at. Sooner or later everyone began to sense something in the patient faces of the Chinese people; in the lavish celebrations they insisted on throwing for us in their war-shattered villages; in the holidays they declared at each place we passed through; in the pathetically flattering signs that called us "gallant heroes"; in the thumbs-up greetings and grins we got from the long lines of ill-equipped, underfed Chinese soldiers trudging wearily back to the front. This was more than just another long drive over dusty roads. This marked the closing of one chapter in this war in the Far East and the opening of another. Thousands of Chinese, American, Indian and British soldiers had fought, worked and died in Burma and China to make this trip possible. The convoy rolled out of Ledo in Assam Province of India even before the Japs had been completely cleared from the Shweli River Valley - the last link in Burma between Ledo and the Burma Road. Three days and 260 miles later the vehicles pulled in to Myitkyina, the biggest American base in Burma, and waited. After a week the convoy got the go-ahead from Lt. Gen. Dan I. Sultan, CG of the India-Burma Theater, who announced that farther down the road the last pockets of resistance were being mopped up. We got up in the darkness next morning, dressed with chattering teeth, drew 10-in-one rations, packed our bedding and equipment in the vehicles and gathered at the push-off point. At 0700 hours Brig. Gen. Lewis A. Pick of Auburn, Ala., who had directed most of the Ledo Road construction and was to lead the convoy, called the drivers together for a last-minute meeting. "Men," he said, "in a few minutes you will be starting out on a history-making adventure. You will take the first convoy into China as representatives of the United States of America. It's up to you to get every one of these vehicles through. Okay, start 'em rolling." As I got into jeep No.32 with Green and Pfc. Ray Lawless of Brooklyn, a photographer for the Signal Corps, I noticed that a Chinese driver was climbing into the cab of every truck as assistant driver. Other Chinese soldiers, veterans of the Burma campaign, were boarding the six-by-sixes to serve as armed guards for the convoy. By 0730 the parking lot was filled with the noise of engines as the vehicles rolled out, turned into the Ledo Road and headed south through the early morning mist. There were motorcycles with MPs, jeeps and quarter-tons, GMCs and Studebakers, ambulances and prime movers. The convoy thundered along, stopping only for a K-ration lunch. We passed American engineers, bulldozers and graders, Indian soldiers digging a drainage ditch, and Chinese engineers building a plank bridge. Fifteen miles from Bhamo we came upon a macadam highway that had been built before the war, and by late afternoon we were pulling into a bivouac area. A GI tent camp had sprung up all over Bhamo in the month and a half since its capture, and it had been policed up considerably. Nevertheless, when Lawless got out of the jeep to take a picture of the convoy entering the shell-blasted city, he found it hadn't been cleaned up quite enough. "Phew," he said, turning up his nose as he came back to the jeep, "what a stink back there. Someone forgot to bury what was left of a Jap hit by mortar." More vehicles joined us at Bhamo, increasing the number in the convoy to 113. At dawn the next day we were off again in the morning mist, bypassing a knocked-out bridge. Soon we plunged into the jungles and hills, following an ancient spur road that had first been used by foot travelers in the day's of Marco Polo and before the war was the main route for supplies from Rangoon.

That afternoon the convoy descended the hills to the fertile, open country of the Shweli River Valley and entered Namhkan, which had been captured by the Chinese 38th Division only nine days before. Before we got through the battle-scarred village, an officer halted the first jeeps. "Looks like you'll have to lay over here a few days," he said. "The Japs still hold several miles of the road up ahead. Some of them are right up there in those mountains, five miles away, with artillery, and they can see every move we make. They forced our guns from one position yesterday with their 150s." The convoy went a few miles past Namhkan, and pulled into a wooded area that had been the Jap stronghold a few days before. There were cleverly concealed emplacements everywhere. Unpacking, we could hear the dull thud of Jap shells miles away and occasionally the sound of Chinese mortars. The drivers were wide-eyed because this was the first time most of them had ever been so close to the enemy. While everyone lolled about the next day, I went around and talked with some of the drivers. All were members of Quartermaster trucking companies. Like Green, who hails from Taylorville, Ill., most of them are from small places like Ada, Okla.; Imlay City, Mich.; Oakland City, Ind.; Oconto Falls, Wis., and Pikeville, Ky. Most of the veteran GI drivers here are Negroes who have been piloting trucks over the Ledo Road for 18 to 24 months. In fact, 90 percent of the convoying on the Ledo Road for more than a year was done by Negro drivers. "Them monsoons was the toughest part of it," said Wilbur T. Miller of Tupelo, Miss. "Last summer, for example, there was several feet of water in some places, higher than our hub caps. The whole road was sometimes just a sea of muck. The rain seemed to cave in a couple of tons of earth on the road in different places every week, and all we could do was set there waiting for a couple of days till the engineers could shovel it off. And boy, that ain't fun." On our fourth afternoon in Namhkan, Gen. Pick got a message that American-manned General Sherman tanks had spearheaded the final break-through along the road to the Burma Road junction, so next morning we were off again. Within two hours the convoy arrived in the village of My-Se - where the last big battle had taken place - for a celebration. Into the leveled town came troops of the Chinese First Army and men of the Chinese Expeditionary Force, who had driven through from Burma and China over the last six months to clear the Japs away from the Ledo and Burma Roads. The two armies were a strange contrast. Soldiers of the First Army, who had fought in Burma, wore sun-tans, GI helmets and British packs, and carried Enfield rifles and tommy guns. They looked plump and well-fed. But the Pings of the CEF, who had fought through from China, wore everything from ragged and patched blue uniforms to clothes they had stripped from the bodies of Japs. Only one man in every squad seemed to have a weapon - usually an ancient German rifle or a Jap Arisika - and all of them looked half-starved. The difference between the extensive American air and land supply lines to Burma and the blockaded land route to China that made military supply in quantity impossible. Looking at the contrast, some of us caught on to the significance of the convoy. From My-Se the convoy wound through barren hills to Mongyu and rolled into the macadam highway at right angles to the Road, past a signpost that had just been put up at the intersection: "Junction - Ledo Road - Burma Road." Just 20 hours before, tanks had cleared this junction and now for the first time in three years a convoy to China had arrived at the Burma Road. But we didn't stop. The trucks swung left, passing more ragged single-file columns of the CEF as we headed for the China border. On top of a hill 10 miles from the Ledo-Burma Road junction, our vehicles halted and the drivers were ordered to put Chinese and American flags and red-white-and-blue streamers over their hoods. The convoy started slowly downhill and halted near an open field. Thousands of Chinese and American soldiers were massed before a platform containing more American and Chinese generals than had ever been on a stage together in the previous three years of the Asiatic War. After the speeches and the band music, Gen. Pick's jeeps drove through an arch decked with garlands of leaves and signs and ribbons. Behind the arch was a short wooden bridge over a muddy stream. This was the Burma-China border. The vehicles crossed the bridge and continued on through the border town of Wanting to bivouac near a tiny village named Chefang. For the next two days the convoy thundered through places that had been the battlegrounds of China during the last six months. The road wound a thousand feet up into the Kaolikung Mountains, which are part of the Hump on the air route between India and China. After hours of threading our way along the narrow mountain ledges we came around a bend and could see below us the blue ribbon of the Salween River, which had been the Chinese line of western defense for two years until the CEF offensive began last May. That afternoon the convoy came out of the hills into Paoshan. A Chinese Army band blared as we rolled toward the city gate, school children waved banners, firecrackers crackled and signs were plastered everywhere welcoming "Commander Pick and his gallant men" and "More M1 munitions and all kinds of materials." That night there was a big party in the Confucius Temple for the whole convoy. There were more speeches, an elaborate Chinese meal, acrobats and gombays. Except for the difficulty of trying to eat with chopsticks, gombays gave GIs the most trouble. Gombay id the Chinese toasting word meaning "bottoms up," and three or four gombays with small tumblers of rice wine, which tastes like wood alcohol and is called jing bao or air raid juice by GIs stationed in China, can be as powerful as a whole case of beer. Nevertheless the Chinese proposed toasts every 10 minutes, and the GIs, in their desire to be diplomatic, soon were feeling no pain at all. Next day, despite hangovers, we made the longest day's trip of the whole journey - 150 miles through rice paddies and up into the mountains again. Finally, at 1930 hours, the convoy halted in an open field. As we fumbled around with flashlights to get our gasoline cook stoves going and put down our bedding rolls, a GI started beefing. "Why the hell is it," he asked, "that every time we bivouac - except for last night when we slept on a concrete warehouse floor - we always have to do it in an open field on the highest and windiest spot in miles?" As it turned out, the next three nights were to be spent the same way. We had all brought jungle hammocks along, but in the open fields the only place to string them was between trucks or guns or jeeps. Most of us just laid our blankets on the ground. This particular night it was so cold that when we awoke next morning there was a frost on our blankets. Lawless had to use our gasoline stove to melt the frost off our windshield. The convoy pushed through Yunnanyi and another celebration, then camped as usual on a high, windy spot about 20 miles away. several GIs were in the streets of Yunnanyi to greet us, and one held up an empty beer case and yelled: "Where's the beer? We only got two cans this month and four in December." From then on, as far as we went into China, we heard the same question whenever we met American soldiers. Beyond Wanting there were stone blocks beside the road that announced the number of kilometers to Kunming. I watched them hour after hour, day after day, as they diminished from 960 to 812 to 668 to 449 to 303 and finally to less than 100. We learned a kilometer is five-eighths of a mile and we periodically figured out our mileage as we drove along.

That night was the worst one of the trip. A heavy rain started around midnight, soaking us and most of our personnel equipment. In the morning we put away our dirty fatigues, took our wool uniforms from our barracks bags and dressed for the last night and the biggest celebration of all. "This Kunming must be a chicken place," said Green. "We even gotta put on ties." Again we put the Chinese and American flags and streamers on each vehicle. Gen. Pick called the GIs together. "I'm proud of you men," he said. "You've brought every one of 113 vehicles through safely. I'm going to see that each of you drivers gets a letter of commendation." The Chinese drivers climbed behind the wheels for the first time and the convoy moved to its destination. We were tired, our clothes still wet from the night's rain, our lips chapped and our faces and necks red with windburn. We all knew what to expect - more crowds and signs and arches and banners an speeches and parties. Beside me, Oscar Green was quieter than usual. For one thing, he'd been feeling pretty sick, so sick we had stopped our jeep the day before at a hospital along the road for him to get some pills. When he came out he said they wanted to keep him in bed there because his temperature was over 100. But he refused to let Lawless or me tell anyone about it for fear he wouldn't be allowed to finish the convoy. The other reason he was so quiet was that he'd been figuring out something in his mind. "They asked for volunteers among the drivers to fly back to Ledo tomorrow, instead of hanging around Kunming for a few days to rest," he said, "and I told 'em I wanted to go. I wanta get behind the wheel of a big ol' GMC and really boot it. This convoy was too much of a circus with all this celebration. I betcha we can make it in 8 days next time instead of 12." "Happy birthday, Oscar," I said, as the first truck convoy to reach China in three years rolled slowly toward the 0-kilometer marker.

|

The photographers - and there were 24 of them, GI and civilian, on the convoy, including two jeeps full from the Air Corps. - ran into trouble now and then trying to get pictures. For instance, when we reached Paoshan, there were a Chinese army band, a line-up of Chinese soldiers and hundreds of civilians along the road to greet us - but they were all on the left-hand side of the road, with their backs to the sun and their faces in the shadow. The photographers saw this would never do so they got the band, soldiers, and civilians to move to the right-hand side of the road so the sun would be on their faces. This was not an easy job, but the photographers managed to accomplish it with much gesturing, pushing and yelling, just as the convoy hove in sight. Then, all of a sudden, a Chinese officer strode up, took one gander at the change and issued an order - a loud and quick one too. Immediately, the band, soldiers and civilians all rushed back across the road and stood in their original positions, with backs to the sun. The photographers howled in anguish. One of them grabbed an interpreter and got him to ask the officer why he ordered everyone back and spoiled what would have made a good picture. The interpreter soon returned with a shrug. "Military custom," he explained, "If they were on the right, the band would have to be at the end of the line instead of the front. The only dog in the convoy, hence the first dog to ever ride the Ledo-Burma Road or to cross the China-Burma border in the last three years in a jeep, was a little brown pup belonging to a Chinese soldier. I asked the GI driver of the jeep in which the dog rode what the pup's name was. "Wanting," he replied. "Is that because Wanting was the first town in China after we reached the border?" I asked, "Hell no," said the GI, "As far as I'm concerned it's because it's always a tree it's wanting." It happened during a weird Kachin tribal dance the night of the big Seagrave homecoming celebration. It was pitch dark and the Kachins go into a circle around a thumping drum and danced faster and faster and faster, working themselves into the proper degree of delirium. A GI who had imbibed a little too much rice wine at the evening's feast somehow got into the circle and soon was prancing around with the Kachins. Suddenly he darted out and started to walk away, shaking his head. Someone asked him what had happened. "Just when I thought they was really knockin' themselves out with that Lindy Hop," he said, "one of 'em turns to me and sez, 'Hey Joe, ya gotta Camel on ya?" By Sgt. Dave Richardson - YANK Staff Correspondent - March 17, 1945 edition. |

U. Khanti is better known in these parts as the Hermit of Mandalay. As a youth, he became so devout a Buddhist that he collected more than $2,000,000 from all over the world for his religion. With this money he financed construction of richly sculptured pagodas, idols, monasteries and temples at the peak of Mandalay Hill and around it. When his work was completed, the hill became one of the most unusual shrines in the Far East. When the Ghurkas with other Indian and British troops of the 19th Division approached the 800-foot hill from the northeast, U. Khanti stepped out of his ramshackle hut at the bottom of it. He saw the forward elements of a Ghurka battalion storming the Jap position on "his hill" and his face brightened with hope. The Ghurkas didn't use the majestic network of stairways - 750 steps each - which climb to the peak of the hill on either side. They clambered up the bare hillside instead. It was easier for them that way, for the Japs had posted guards on all the stairways of the holy hill. There was very little resistance until the Ghurkas were halfway up, and someone down below said the Japs must have been caught unawares. The Ghurkas in the storming party said they had heard girls' voices singing what they called "gay Japanese songs." Perhaps the Japs were entertaining their comfort girls. Or being entertained. Whichever, this was evidence of one of the reasons U. Khanti hated the Japs. His holy hill was being desecrated. Another reason for his hatred was that the missionaries of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere had leveled with bombs much of his beloved city of Mandalay and had starved the population. The once happy, prosperous people who had come to the hill to worship had been sad and hungry during the three years of Japanese occupation. U. Khanti heard the artillery barrage let go as the Ghurkas approached the hilltop. After it, there was only the relative battle quiet of a few stray shots. Then silence and the bodies of Jap soldiers strewn before massive figures of Buddha and over the broken stairways and over the floors of one of the temples. The Ghurkas withdrew, leaving the Jap bodies and the empty beer and sake bottles that lay near them. There was no sign of the alleged comfort girls. If they had been there, they must have left by a southern exit.

For the southern side of the peak had still to be cleared. U. Khanti watched men of the Royal Berkshires take over the assault to the south. There the Japs hid inside the temples, behind pagodas and between huge Buddhist idols. The fight for possession of the southern peak continued for three days. About 20 of the enemy escaped death until the last by taking refuge in a tunnel running through the hilltop from east to west. The tunnel, made of rock and concrete, was shellproof. It would have been too costly to try to take it by a frontal infantry attack, and an air strike was ruled out because the British did not wish to damage the holy structures any more than could be helped. U. Khanti was still watching, now apprehensively, when a British sergeant from Essex approached his CO. "Sir," he said, "with your permission I would climb over the tunnel and throw a tin of petrol into the bloody thing. Then I would follow up with a grenade and see what develops." "Ordinarily," said the CO, "I would take a dim view of such a stunt, but carry on." With a large can of gasoline in his arms and a pair of grenades dangling from his belt, the sergeant climbed cautiously above the tunnel toward the top of one of the entrances. When he got there, he leaned over and hurled the gasoline into the black opening, can and all. A second later he followed through with a grenade. Flames and black smoke poured out of the entrance. U. Khanti and the other spectators heard screams and groans from the bowels of the tunnel. Seven Japs, one by one, ran flaming from the tunnel and jumped, torchlike, from the top of the steep hill. Two British soldiers rushed into different tunnel entrances and pumped lead. Next morning 13 Japs were found dead in the scorched corridors. The battle of Mandalay Hill was ended. The second phase of the Battle of Mandalay - clearing out the city - wasn't far from U. Khanti's hut either. It centered around an ancient fortress - Fort Dufferin - protected by a red-brick wall 26 feet high and surrounded by a 60-yard moat. The Japs holed up here were able to keep the 19th Division at bay for 13 days. Several attempts were made to capture the fort during that time. While the Royal Berkshires were fighting on the hill, a battalion of Indian troops tried unsuccessfully to take Dufferin. They used a 5.5 gun placed only 500 yards away from the fort's northern wall in this first assault. It threw 100-pound shell after 100-pound shell against the target. When a breach had been made, the Indian troops advanced. They advanced only to meet a withering barrage of machine gun fire at the most. In a few minutes the ground was soaked with the blood of the wounded. Bearded, turbaned Punjabis ran the gauntlet of heavy Jap fire to carry out casualties on their shoulders. And the other Indian troops were ordered to withdraw. In the next few days several air attacks blasted the fort, again from the north. Two more infantry assaults were launched on two different nights, but both failed. By the 11th day of the battle, the troops of the 19th had fanned out to every section of Mandalay. Only Fort Dufferin remained in Jap hands. Finally, on the 13th day, wave after wave of Mitchell bombers dropped 1,000-pounders on the northern walls. Then, just as the smoke settled, the infantrymen prepared to storm over the rubble and into the fort. They were poised for their charge when someone pointed to the breach in the wall. Two men stood there, one with a white flag, the other waving a Union Jack. The two men moved down to the infantry lines and explained everything. They were Anglo-Burmans who, together with 300 other refugees, had been imprisoned by the Japs. The Japs, they said, had fled to the south. "There isn't one left in the fort now." With this ending to the Battle of Mandalay, U. Khanti sent one of his followers up the holy hill to check the damage to the statues of Buddha, the pagodas and the temples. Soon again his followers would be climbing the hill to worship. Maybe they wouldn't look so hungry and sad.

|

SUPER LOAD.

Bomb-bay doors open and tons of bombs pour out of these B-29s as they fly over enemy positions in Burma.

Their target was a Jap supply depot near Rangoon.

SUPER LOAD.

Bomb-bay doors open and tons of bombs pour out of these B-29s as they fly over enemy positions in Burma.

Their target was a Jap supply depot near Rangoon.

|

Compiled from various editions.

|

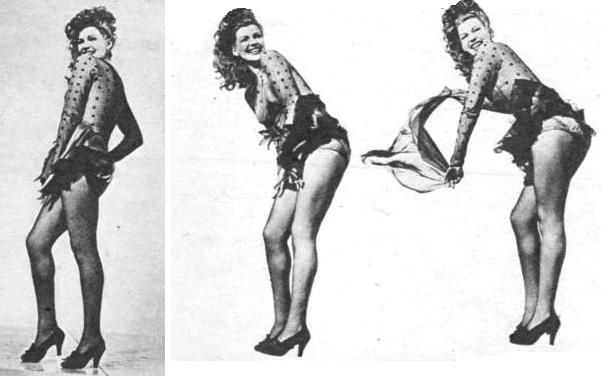

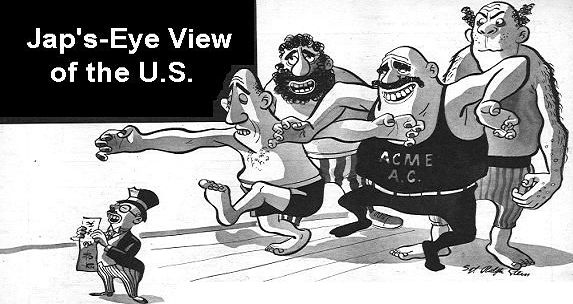

Now that the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere is undergoing seaborne alterations, Japs show new interest in things American. As part of the official orientation program aimed at acquainting them with the habits of possible visitors to the island paradise, Radio Tokyo recently beamed a report on the U.S. by one Goro Nakano. Goro, a mean man with a statistic, used to be New York correspondent for the Tokyo newspaper Asahi. His lowdown on life in the U.S. is several degrees more intimate than the cellar of a Wac's barracks bag. In four outstanding evidences of Yankee barbarism, he finds two that deal with sex - not a bad average for any league. But his first beef is the shocking lack of sportsmanship in U.S. sports. Goro, who on his New York tour of duty probably never watched the Dodgers apply the needle to their opponents, says that baseball is a fair game on the surface; so is football. But neither of these are typically American. Hell, no. The real American sport is wrestling, and wrestling in America, Goro reports, is performed by "monsters who are like spooks, six or seven feet in height" and bearing "such outrageous names as Man Eater, Man Mountain, Champion of Hades, King Kong or Gorilla of Siberia."

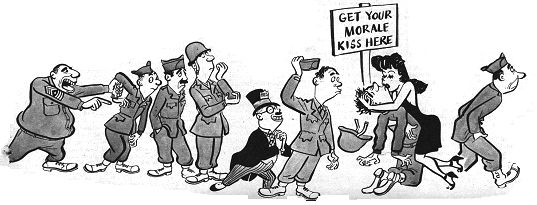

A quick look at Broadway, which seems to have produced such outstanding dramas as "Tobacco Road," "Tobacco Road," and "Tobacco Road," shows Goro a theater where all the plays are barbaric. "The more cruel, the more popular they become," he mutters and turns his attention to Hollywood. In the War Bond selling drives, according to his shocked whisper, Hollywood actresses do nekkid dances. "Each time the actress strips off some of her clothes, spectators are made to buy more bonds. Thus by barbaric methods they bolster the dime-store patriotism of the ignorant Yankee masses." Goro forgets to mention that the drooling induced by such entertainment makes it much easier for us to lick the stickum on our War Stamps. "Actresses and young girls," Goro says, "go into Army camps giving comfort kisses to the servicemen. One actress boasted of giving 15,000 kisses. The morale of the barbaric Yankee soldiers is being stirred up." In closing, Goro, by this time a trifle stirred up himself, says: "These evils should convince the Japs that America is a barbaric nation unparalleled in the world and should inspire a hatred in the Japanese people." Frankly, the only thing we're worrying about is how to stop the Jap stampede on War Bond lines and enlistment offices. Which way to the nearest orgy, Goro?

|

|

Jinx Recalls Her Far East Gallivanting

MISS FALKENBURG, dressed in a white dress of Mexican wool with "Jinx" printed all over it in red, bubbled over like a girl just back from her first dance. What she was back from was no dance, but a USO tour of the India-Burma and China theaters of war with Pat O'Brien's entertainment unit. This gang played some 84 performances (exclusive of hospital shows) for GIs. Jinx and the gang were supposed to give only 54 performances on the trip. The rest were buckshee, put on because, Jinx said, "Once you get going out there and see the guys, you want to stop and do a show everywhere, for everybody." From the time we got up to the time we were ready to fall into bed, it was like a continuous opening night. Some places I think the soldiers must have come out of the woodwork. The reception you got everywhere was enough to turn your head, but, looking at the way the men were living and the roughness of it all and how far they were from home and how they were staying there when you were going back, your head didn't turn. You felt like cheering them instead of being cheered." It was all new to Jinx and close to her because she has two brothers in service. The floor of her hotel room was strewn with souvenirs - a coolie hat, silk prints, slippers, gadgets galore - and her mind was strewn with reminiscences. "I don't know what was most exciting, most interesting. There was a B-29 base where we had maybe the most intense audience of the entire trip. They left when the show was half over to bomb the Japs. I sat in with the men at the very tail end of the briefing for that mission. When one of them touched my shoulder, it was electric, as if he'd hugged me - it was that tense. "Everything you saw was new and exciting. I was always taking shots - you know, 'the hook' - but I was so busy they didn't have time to make me sick. The men were wonderful to talk to and easy to talk to, and we tried to talk to everyone that wanted to talk or take a snapshot or play ping-pong. We usually played a stiff game of ping-pong in day rooms to relax ourselves." "And now I've got to get used to sleeping without a net again. I want to go out again, overseas somewhere, as soon as I can. The nets we used over there, by the way, were for keeping rats out - not mosquitoes. Once us girls had a huge rat under one of our beds in China. It just sat under the bed going 'Chomp, chomp, chomp' like Bugs Bunny. We squealed at first but we got used to it, and it was still chomping when we fell asleep." "Everything reminds me of something else. I still can't talk straight about it." She couldn't because she was still filled with the same excitement that carried her through her 84 shows - the same excitement that sparkled out of her as she stepped from the plane that brought her over the Hump, dressed in a red sweater, GI shorts and red stockings, and made Gen. Joseph Stilwell remark: "Now there's a real firewoman!"

|

|

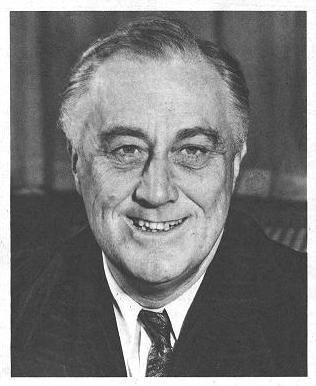

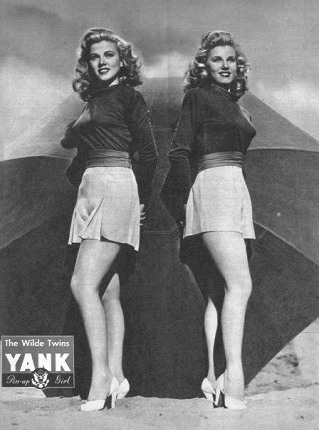

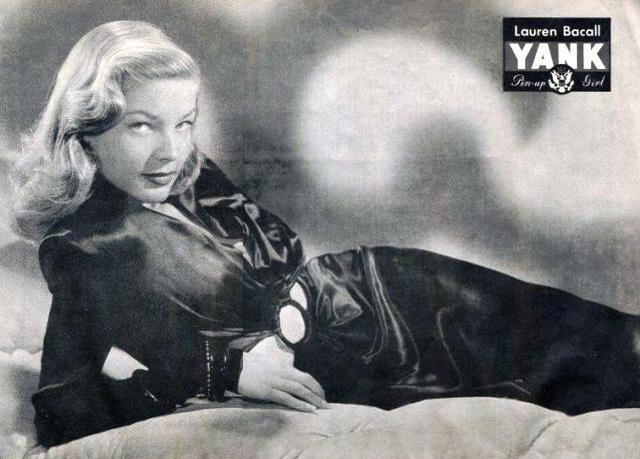

CLICK ON ANY PIN-UP FOR FULL SCREEN IMAGE

Most of us in the Army have a hard time remembering any President but Franklin D. Roosevelt. We never saw the inside of a speakeasy because he had prohibition repealed before we were old enough to drink. When we were kids during the depression, and the factories and stores were not taking anybody, plenty of us joined his CCCs, and the hard work in the woods felt good after those months of sleeping late and hanging around the house and the corner drug store, too broke to go anywhere and do anything. Or we got our first jobs on his ERA or WPA projects. That seems like a long time ago. And since then, under President Roosevelt's leadership, we have struggled through 12 years of troubled peace and war, 12 of the toughest and most important years in our country's history. It got so that all over the world his name meant everything that America stood for. It meant hope in London and Moscow and in occupied Paris and Athens. It was sneered at in Berlin and Tokyo. To us wherever we were, in the combat zones or in the forgotten supply and guard posts, it meant the whole works - our kind of life and freedom and the necessity for protecting it. We made cracks about Roosevelt and told Roosevelt jokes and sometimes we bitterly criticized his way of doing things. But he was still Roosevelt, the man we had grown up under and the man whom we had entrusted with the staggering responsibility of running our war. He was the Commander in Chief, not only of the armed forces, but of our generation. That is why it is hard to realize he is dead, even in these days when death is a common and expected thing. We had grown accustomed to his leadership and we leaned on it heavily, as we would lean on the leadership of a good company commander who had taken us safely through several battles, getting us where we were supposed to go without doing anything foolish or cowardly. And the loss of Roosevelt hit us the same way as the loss of a good company commander. It left us a little panic-stricken, a little afraid of the future. But the panic and fear didn't last long. We soon found out that the safety of our democracy, like the safety of a rifle company, doesn't depend on the life of any one man. A platoon leader with the same training and the same sense of timing and responsibility takes over, and the men find themselves and the company as a whole operating with the same confidence and efficiency. That's the way it will be with our Government. The new President has pledged himself to carry out its plans for the successful ending of the war and the building of the peace. The program for security and peace will continue. Franklin D. Roosevelt's death brings grief but should not bring despair. He leaves us great hope.

|

YANK

THE ARMY WEEKLY

China-Burma-India Edition - Part Two

Copyright © 2005 Carl Warren Weidenburner

CBI EDITION INDEX

Visitors

Since March 31, 2005

| YANK, The Army Weekly, original publication issued weekly by Branch Office, Information & Education Division, War Department, East 42nd Street, New York 17, N.Y. Reproduction rights restricted as indicated on the editorial page. Entered as second class matter at the Post Office at New York, N.Y., under the Act of March 3, 1879. Subscription price $3.00 yearly. China-Burma-India Edition printed by G.B. DASS at the Eagle Lithographing Co. Ltd., Calcutta. |

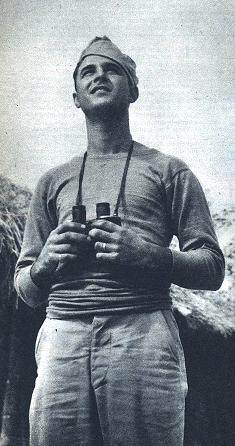

Pvt. George Karastamatis of the Bronx, N.Y., is on duty as ground observer at an AW station in northern Burma.

Pvt. George Karastamatis of the Bronx, N.Y., is on duty as ground observer at an AW station in northern Burma.

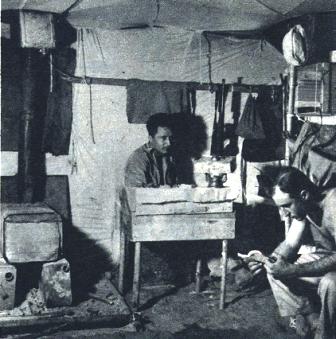

These quarters were built by Naga natives. At the table is Cpl. Dale Calderon, cook, and right is Pvt. Karastamatis.

These quarters were built by Naga natives. At the table is Cpl. Dale Calderon, cook, and right is Pvt. Karastamatis.

Cpl. Russell Higgerson of Albany, N.Y., turns school teacher. He is trying to get two Naga kids through the English alphabet.

Cpl. Russell Higgerson of Albany, N.Y., turns school teacher. He is trying to get two Naga kids through the English alphabet.

Sgt. Eugene Schultz of Buffalo, N.Y., medic for an observation team, treats the foot of a Naga woman.

Sgt. Eugene Schultz of Buffalo, N.Y., medic for an observation team, treats the foot of a Naga woman.

Pfc. Gerald Shenker of Brooklyn, N.Y., and T-5 Frank Warmuth of Corona, N.Y., pay out wire on a line project

across a river in India, using portable reels.

Pfc. Gerald Shenker of Brooklyn, N.Y., and T-5 Frank Warmuth of Corona, N.Y., pay out wire on a line project

across a river in India, using portable reels.

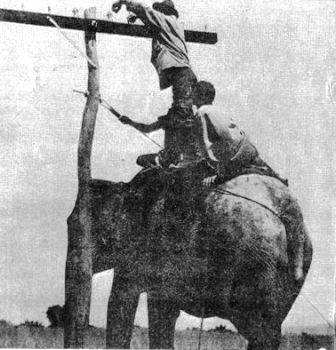

While this elephant stands sreadily and patiently by, a Signal Construction man ties in a communications line.

These animals are a big help for this type of work because the swampy terrain makes it difficult for GI trucks.

While this elephant stands sreadily and patiently by, a Signal Construction man ties in a communications line.

These animals are a big help for this type of work because the swampy terrain makes it difficult for GI trucks.

A GI and Pioneers of the Indian Army hack a right of way through the jungle, blazing the trail for the wire crews

to follow.

A GI and Pioneers of the Indian Army hack a right of way through the jungle, blazing the trail for the wire crews

to follow.

An elephant supplants the GI truck to transport these GI Signal Construction men through the swamplands af Assam.

Jumbo comes in handy when the men go out to check up on their communications lines and he drags his lunch along.

An elephant supplants the GI truck to transport these GI Signal Construction men through the swamplands af Assam.

Jumbo comes in handy when the men go out to check up on their communications lines and he drags his lunch along.

A 14-foot pole in the hands of T-4 Joseph Johnson of Yonkers, N.Y., sinks deep into the monsoon-made lake covered

with water lilies. Johnson keeps the wire lines opne.

A 14-foot pole in the hands of T-4 Joseph Johnson of Yonkers, N.Y., sinks deep into the monsoon-made lake covered

with water lilies. Johnson keeps the wire lines opne.

T/Sgt. Alfred Holden of Los Angeles, Calif., takes a break from line stringing to talk to a Punjabi bridge guard.

T/Sgt. Alfred Holden of Los Angeles, Calif., takes a break from line stringing to talk to a Punjabi bridge guard.

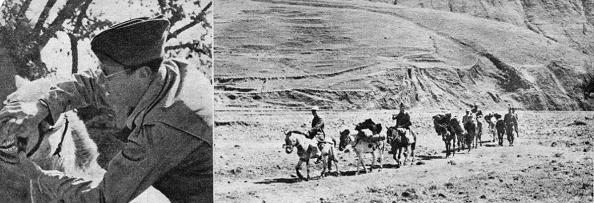

Maj. Charles Ebertz was a veterinarian in civilian life.

A pack train of GIs and Chinese follows a mountain river bed on the way to a Lolo village.

Maj. Charles Ebertz was a veterinarian in civilian life.

A pack train of GIs and Chinese follows a mountain river bed on the way to a Lolo village.

A bunch of horses rushes into a corral to the feeding troughs.

A bunch of horses rushes into a corral to the feeding troughs.

Lo-Tai-Ing, tribal chief of the Lolo village visited by the GI horse buyers, tries out on M1.

Lo-Tai-Ing, tribal chief of the Lolo village visited by the GI horse buyers, tries out on M1.

Lolos, wearing capes, in a town just beyond the Yellow River.

Lolos, wearing capes, in a town just beyond the Yellow River.

Blindfolded Jap prisoners are lead into headquarters.

Blindfolded Jap prisoners are lead into headquarters.

The brutes, "huge and horrible looking," are imported from foreign lands (possibly Japan?) and pitted against

good-looking American youths. The good-looking American youths get into the ring with the monsters and tear them

apart in a contest that is considered fair "as long as edged tools are not used." Goro, whom we visualize as a

pleasant little chap with horn-rims and a couple of edged tools protruding from beneath his upper lip, is sick to

his stomach at such a spectacle.

The brutes, "huge and horrible looking," are imported from foreign lands (possibly Japan?) and pitted against

good-looking American youths. The good-looking American youths get into the ring with the monsters and tear them

apart in a contest that is considered fair "as long as edged tools are not used." Goro, whom we visualize as a

pleasant little chap with horn-rims and a couple of edged tools protruding from beneath his upper lip, is sick to

his stomach at such a spectacle.