879th ENGINEER AVIATION BATTALION China-Burma-India Theater of World War II Edited by FREDERICK P. COREY with illustrations by REX R. CORK* |

|

for the perpetuation of democracy in America and throughout the world:

|

Prologue

This is a story of men and mud, a story of a battalion of Aviation Engineers, activated, trained and shipped across half a world to become a part of the Allied striking forces which reversed the Japanese in their conquest westward to India, turned their greedy fingers from Burma and opened the lifeline to China. It is a true story. Hence the reader will not find inscribed in the foreword (though he may, in perusal, come of the opinion that surely it should have been) the forewarning that "in the writing hereof no character or circumstance is designed to bear resemblance to any actual person, living or dead, or to any true event".

Yet, too, while it is a story, it is only a tangible reference to the whole story, another of many such written in "blood, sweat and tears" in the lives of our fighting men around the world, the honored dead have gone on to God, the muffled tread of marching divisions and the roar of hordes of bombers has receded into the past and those lives of the men and women who wrote the stories have gone or are going home.

We were born 1 March 1943 at Westover Field, Massachusetts, just outside of Holyoke and Springfield. We are not an old battalion at the writing; yet, measured in the age-long days and nights and months of war, we have come far and neither are we young.

We were formed from a trickle of the enormous inflow of manpower drawn from the length and breadth of America to defend her and her way of life. We were rallied around cadres of officers and men trained earlier to the Army ways of life, and we grew into our uniforms under their guidance until instructor and recruit were fused into one entirety.

But to say that the fit of a uniform, the precise alignment of a right file and dexterity of the Manual of Arms made us Engineers would be a gross error. These accomplishments helped to make us soldiers. We read much of the eligibility to wear a pair of wings or to earn the Infantry Badge. Like these, the Castle insignia of the Corps of Engineers does not knight us to the authority of the title; but rather our skill and resourcefulness and training as Engineers enrolls us in the Corps.

We were fortunate, as the past two years have well proven, in assigning a reasonably strong working nucleus of officers and men who had the prerequisites of an Engineer. Those men have schooled us, aided by necessity for the success of our mission, in our entitlement, though far short of cum laude, to the wearing of the castle.

A prologue does not license us to an overabundance of detail and so this resume of our seven months at Westover Field must needs be as insufficient in covering our adolescent years as were some of the qualifications we possessed to cover the requirements of an Airborne Table of Organization, (for indeed military occupational titles were of necessity awarded as indiscriminately as land grants in a "shyster's" sub-division).

We did mature though and after qualifying for M-1 marksmanship at Rock Valley Range, grounding our machine gunners in the fundamentals of their weapons at Price's Neck, Rhode Island, and passing through the valley of indecision (Johnny keep your tail down) known as the "infiltration course", we were "shaded in" on the S-3 training chart as accomplished in the offensive and defensive use of small arms fire-power as time would permit instructing. We learned too, which end of an asphalt kettle dispensed the asphalt and something of the nomenclature of the diesel engine. After completing a couple of runway construction jobs, fishing a crashed P-47 out of a lake in the hills north of the base (a task which involved cutting a road and building dock and hoist facilities) and taking part in an Engineer recruiting drive down Boston way, we emerged for full-dress parade ("pitch shelter-halves to the left") and graduation day.

The events of the world were moving with the swiftness difficult to conceive as we boarded the troop-train early in October bound South to Laurinburg-Maxton, North Caroline, for glider and transport training. The almost Civil War vintage of the coaches we occupied gave insight to the vast amount of industry and transportation mobilized for the execution of the war.

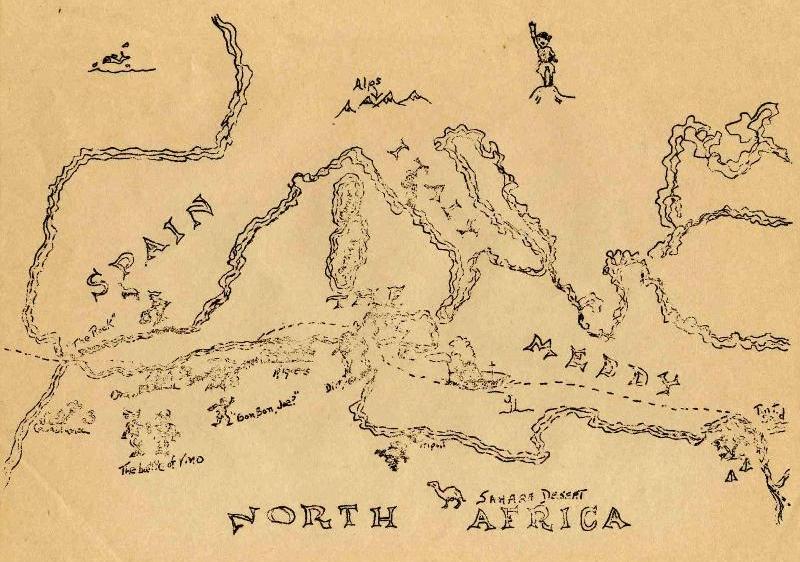

American troops were pouring into England and Ireland. Rommel had been cornered in the sands of North Africa and Allied invasion forces has made Sicily and Salerno names on the lips and hearts of us all as they began the push up the boot of Italy toward the Alps. Lend-lease convoys made the arduous trip around to Murmansk in ever increasing numbers. Stalingrad had stood and the long struggle for repossession of the U.S.S.R. begun; but the German U-boats in the North Atlantic still took their toll of shipping.

Japan had her tentacles stretched out to the far reaches of her stolen empire and though our forces in the Pacific made headway in spite of top priority shipment to Africa and England, we knew that it was to be no pushover in either the Orient or in Europe. The defenders of Corregidor had long been silent and anxious hearts awaited word of them.

In all this expanse of war we were just one more small unit warming up on the sidelines awaiting the coach's curt nod to join our comrades in the battle which we were aware was being played for keeps.

The nod was not long in coming. Furloughs canceled or cut short and our glider training (if ever really scheduled)

suspended, we entrained after only a month and a half at Laurinburg-Maxon and hurried to meet a convoy deadline at

Hampton Roads, Virginia.

It was the night of December 14, 1943. Remember? Pushing aside the heavy black-out curtains and climbing out onto

the wet dock of the U.S.S. John P. Mitchel or H.M.S. L.S.E. 2, or the U.S.S. Huntington, we got a GI's view of our

first big convoy making up and getting under way in the rapidly closing darkness. It was pretty cold and damp and

we bugged our overcoats about us, and our life-preservers only casual acquaintances then; but soon to become bosom

friends in the close companionship of the days to follow. We felt quite an assortment of emotions and expectations

milling around inside us and seeking an outlet which only time could give.

That was off Hampton Roads, Virginia, where we had come aboard earlier in the day and stood out to see to await the

rest of the convoy. As we stood by the rail watching, there were ships to the starboard, port, bow and stern still

jockeying for positions as blinkers talked a silent language and the pilot lights punctuated the darkness with

cautious works acknowledging their whereabouts to their neighbors.

It must have been about 0300 hours on the morning of our third day out. A pretty rough sea was rolling; rough at

least for Liberty Ships and Landing Craft. We had listened all night long, aboard the Mitchel, to the banging

of pots and pans in the galley, and the rattle of chains and loose tackle on deck. Not being able to sleep anyway;

what with the rolling of the ship and the noise, and for some intense longing, feverishly nurtured in seasickness, to

be dead and away from it all; a few of us braved the uncertainty of the deck and greater uncertainty of our legs and

stomachs (which hadn't had a Chinaman's chance as yet to become sea-going!) and groped our way to the galley and the

compartment where were ate, to put a stop to some of the infernal racket. The coffee boiler had spilled over, and

along with the sink of dishwater and such other liquids and solids as eggs and potatoes and bacon and the overflow

from that necessary but never-to-be-trusted seaman's version of a slit-trench at the top of the landing, it all made

for a little ocean of its own. Pot covers and trays, dish-pans and bars of soap made a miniature invasion fleet to

rival any "Gulliver's Travels" was ever able to boast. We went in with ropes, belts and dish-rags and brought the

craft to anchor, mooring the dish-pans to the stair rail and taking such other measures as might at least lessen the

noise.

But we'd be a long time and a lot of type and ink describing that journey which was, for the most of, us born to the

rolling hills of American country-side or the familiarly and sure pavements of the city, our first venture aboard

anything bigger than a fishing schooner, Hudson River Day-liner or a Mississippi flat-boat.

Father Neptune was merciful at least. Men who has lived an unhappy eternity in their bunks during those first rough

days ventured above-board and found life worth the living again. How many nights as we stood by the ship's rail and

talking far into the small hours and watching the stars shift position when we changed course with a two degree tac

alternately to starboard and then to port to elude any submarine pecks which might be following along awaiting the

opportunity to strike and submerge before our destroyers and corvettes, which mothered us along, could come in for

our defense. How often we stood in the bow for hours on end watching the myriads of phosphorescent sparks swept away

as the ship knifed forward and the water parted on either side like a freshly turned furrow on the farm back home.

There was even a little fishing as some of the fresh water fly and plug artists tried a hand for bigger game over the

fan-tail. There was an occasional school (or would you say herd?) or dolphins as we bypassed the Canary Islands and

patches of seaweed along the way. On the nineteenth day out we swung by the Canary's and worked our way up the

Moroccan Coast. There was the never-to-be-forgotten scene as the ships of the convoy crowded together in the dark

that night for passages through the Straits, cutting across prow and stern so close to each other that the Captains

shouted through megaphones as they arranged the order of passage. It was an impressive view of the Rock of Gibraltar

which lay before us as we passed by in the early morning and the ship's rails were crowded as we looked on the rolling

slopes of Spain and Spanish Morocco. Land was beautiful after an endless panorama of ocean.

As we steamed into Oran, Algeria, and looked up at the buildings about us, we had our first glimpse of a city which

had been on intimate terms with war. Sunken ships lay in the outer and inner harbors. Their superstructures rising

above the water. Barrage balloons ringed the water front and the noise of hoists and hammers rose up from the dry-docks

and work barges. We disembarked and wedged ourselves into "6x6's" (at least those were familiar) and rumbled off to

the staging area as darkness crowded in on the first leg of our journey.

So this was North Africa - with crowded "winded street" Oran and the eucalyptus-lined roads circling through rolling

hills quilted with grape vineyards and yellow with the bloom of wild mustard, with the donkey carts and the crude

wooden plows used to cultivate the vineyards. How quickly the cold settled in at sundown and how reluctantly we left

our "sacks" to stand reveille in the black frosty air at dawn. What damnable contraptions we wired together for tent

stoves. All this we'll remember and more...

The people, French, Arabs, and Italian. How differently they lived. The backwardness, filth and poverty of the

masses brought sharp awareness of the fortunate standard of living known to us, back home in America.

We began to wonder after our first day if "Uncle" had set out to clothe the world! Almost every Arab or Frenchman we

met wore at least one item which a well-dressed GI once wore. That was the outstanding indication of the troops who

had preceded us. The battle fields had grown over with grass again, though empty shell cases, the track of a tank

or an old truck wheel and crater holes pointed in mute evidence to the days before these hills sheltered the tents of

staging area. But the clothes the Arabs wore, a shirt on one, a pair of cast-off shoes on another, were unmistakable

signs of the Yankee who came before us and swapped his pants for the highly inflated prices the natives offered, or

for a job of wine or maybe as a gift to a barefoot boy in rags shivering on a cold morning.

When it comes to trading though Jeez man, those Arabs either knew all along or else they learned fast! Some of

them could out-trade the shrewdest pawnbrokers who ever invaded Flatbush and we should know!

There are members of this battalion of Engineers who profess to a vast knowledge and a thorough education in the

avocation of drinking; but most of it stems from the "cognac and vino days" at Oren and Algiers, North Africa.

Many stores you d never believe now (nor would they who told them) had their origin along the streets at Oren or

along the road which threaded its way amongst the grape vineyards to the little French village of St. Louis. Some of

that stuff could only have precluded the advents of the atomic bomb! That is reflective comparison; for of course

nobody had heard of the atomic bomb then; but, brother, the world would have had instantaneous usage had it been known.

Many a GI will lean back in this chair at the club in the years to come, glass in hand, and remember the war years

when his glass, or beer bottle, or canteen cup held a slug of "saki" or "Fighter Brand" (two types of liquid fire

which we became acquainted with later in our army careers) or cognac.

Pops told us of the old French "Forty and Eight" after his last war. Well, they must have known we were coming back

and saved them for us. (Incidentally, Dad, they haven t become any more comfortable between wars!)

We entrained for the three-hundred mile trek to Algiers aboard these box-car Pullmans and survived the journey.

How in damnation the French ever got forty men or eight horses into one of those rolling coffins will continue to

baffle us to the end of our days. Maybe though just maybe - they could. You see, we split the quota and averaged

twenty men and baggage to the car. This required sleeping in relays; but when standing we jounced around a lot.

It may be that the French were wiser. By standing forty to the car one could relax in slumber while standing,

without the danger of falling, and all could sleep at once if they desired!

Dining facilities were personal as personal as only a can of C-rations can be. It s all yours when you open it and

you don t feel a bit piggish because there are cans enough for everybody. Dessert is a sure bet a fig-bar and candy.

The beverage is something else again and a matter of fortune or misfortune. Somebody heaves you a can. Maybe it has

lemon powder or perhaps you have cocoa or coffee. It it s one of the latter and your accommodations are near enough

to the head of the train to permit a dish forward to the engine during a water stop, you can get the engineer to pour

you a cup of hot water off the boiler and you ve got the grand finale to a fair meal (until it is repeated day after

day after day!)

Yes, that was quite a trip too. Remember how it was in the mountains when we sat in the doorways watching the

countryside? (Some of it was really beautiful). When we d approach a tunnel, everybody would pile back into the car

and a frantic effort to get the doors shut would ensure. Woe unto those unfortunate enough to fail because of a

jumped track or other cause. Their only salvation then lay in the hope that the tunnel was only a short one; and

even so when the train charged the car was filled with smoke and cinders.

We usually saved the candy from our rations to toss to the native kids who crowded the train at every village stop,

or to trade for oranges and tangerines along the way.

We remained in Algiers five days. The more fortunate managed to get into the city and found it more spacious and

intriguing then Oran. There were department stores, hotels and restaurants incorporating State-side familiarities.

But there were the same kids, or more like them, shouting, "Hey, Joe, shine?," street peddlers, chic women fashionably

dressed, Arabs in flowered robes or dirty rags as befitted their prosperity and uniformed GI s, British Tommies and

French soldiers pushing along with the flow of pedestrian traffic or congregating at the street corners to get

acquainted. After a month s stay in Africa, gleaning excerpts from the conversations of those coming and going, some

of them referential to the dangers still prevalent in the Mediterranean passage, it was rather to be taken for granted

that we should feel somewhat apprehensive of our coming voyage.

Crowded as a New York subway at the five o clock rush hour and hotter than seventeen shades of hell. That was

compartment E-4 or F-2 or any other of the converted store rooms below deck and forward aboard the Nec Halles,

a Scottish ship sold to the Greeks and later returned to His Majesty s service after the Third Reich overran Greece,

and docked temporarily at Algiers on the twenty-fourth of January for the express purpose of loading her ample belly

with American troops bound out to India. We were amongst them and it seems now, in reflection, that we must have been

an afterthought - one last mouthful taken on in the optimistic belief that somewhere there would be room for us.

She was a splendid ship and in the prewar days when her lounges and staterooms were less crowded and the bar was open

on "A" Deck she must have afforded a lot of comfort and pleasure. But we knew her in war garb and will remember her

as she was on that run through the Mediterranean, the Suez, and across to India.

It is said that you can measure the contentment of a company of soldiers by the amount of "bitching" they do about

everything in general from "chow" to personnel. When the undercurrent of complaint is strong, things are running on

a pretty normal keel; but when the troops adopt a reticent attitude to "the Old Man s" latest decree and the Top Kick s

sharpest bark, then look deep, brother, for there is probably something smoking! By these standards we were a happy

lot as we downed the kidney stew and recited only a modest number of choice words when we opened an over-ripe egg on

the only piece of bread we had for breakfast. We slept wherever we could; in hammocks suspended from the duffle racks

overhead, under the mess tables and on them. In the morning when the compartment chore-master blew his little whistle

and we struggled to put on our shoes in a two by four space that would make an upper berth on the Pennsylvania seem

like a deluxe bedroom, the guy who hung his hammock over your head had the prerogative of standing on your shoulders

while he dressed, and the chap who slept beside you had no alternative but to sit in your lap; but we had come to

accept consolidation as Standard Operating Procedure by now and it all made for chumminess.

Then there were the ham sandwiches bought at a dollar each on the ship s black-market which proved that there was more

aboard than kidney stew and fish chowder though not in sufficient quantities to avoid the highly inflationary prices

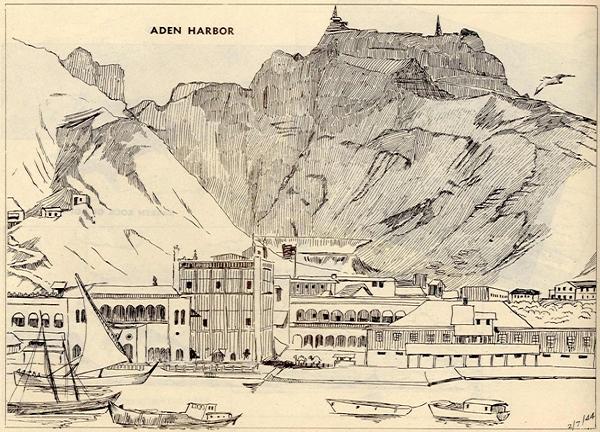

demanded by those who had the inside track. There were boat-drills, crap-games, and the afternoon we tied by at Aden

to refuel and were allowed to keep the hatches open and the port-holes in the few stuffy state-rooms the "brass" and

the "zebra-arms" were able to wrangle. There was ginger beer and Egyptian candy and the lively mealtime discussions

from which Holmes could have gleaned another volume for "The Autocrat at the Breakfast Table."

None of the fears of enemy action we had entertained at the outset of the voyage materialized, though once or twice our

escort startled us when they rolled a few "ash cans" into the deep somewhere up ahead letting go with a wallop which

shook the old tub from prow to fan-tail. How acute was the danger the depth charges may have dispensed with or

thwarted, we never knew. Our most probably danger lurked in the possibility of sudden air attack in the strait off

German-held Crete; but fortune sided with us again and a rousing gale of the sort which beset Paul with less fortune

near this spot in Biblical days, gave us cover pas the point of danger.

Port Said and the Suez afforded points of scenic interest and the evenings on the Red Sea contributed a couple

memorable sunsets. This is by no means the story of the voyage, but perhaps a reminding foot-note that such a story

does exist at the beck and call of those who lived it.

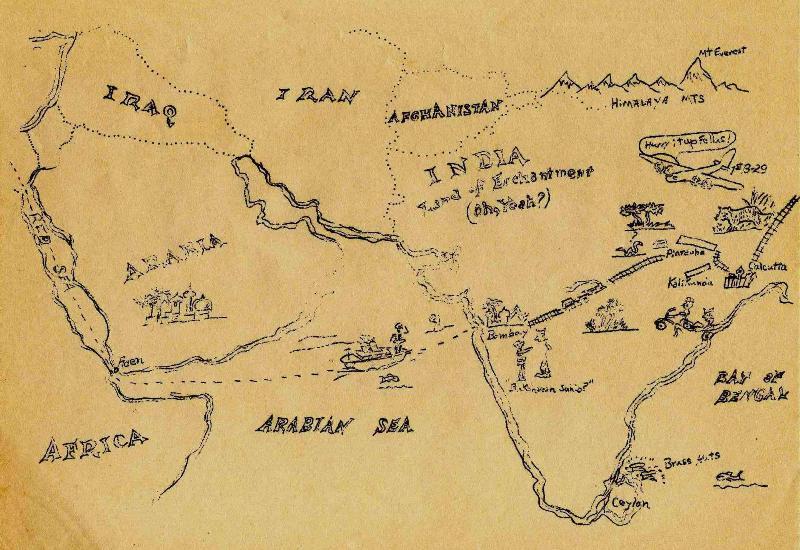

The oceans behind us, we had our first glimpse of Britain s largest imperial possession "The Land of Enchantment"

(other titles have been recommended now) one morning in mid-February. Raven-like birds swooped and darted about the

superstructure of the ship and spun down from high overhead to clutch in flight the pieces of bread we tossed aloft

for them. Crude sailing sloops, resembling the Viking Ship of old, ran out before the wind and seemed to frequent

the whole harbor, looking clumsy and frail beside the greyhounds in war paint and the liberty ships and tankers lying

at anchor. The Bombay skyline was lost in the heavy haze which hung low over the harbor, red in the sun s brightness.

"Baksheesh, Sahib? You, Rajah, Me poor man, baksheesh!" How often we were to hear this chant, we little suspected,

as we boarded the third and fourth class cars of the Royal Indian Railway to be shunted across India to the little

village of Piaradoba, some ninety miles out of Calcutta.

Class distinction in India goes to extremes hitherto unknown to us in America where we struggled with the negro

problem and had heard that in Boston, "the Lodges spoke only to the Cabots and the Cabots spoke only to God!" Here

we were to learn that if you "lived on the other side of the tracks," the repercussions ran deep and colored the life

of the whole country. Inextricably interwoven into the numerous religions and social brackets for generations,

marriage, business and politics all took their cue from the table of allowances the various religions dictated.

Piaradoba was well on the way to becoming a base for the new super hush-hush bomber, the B-29, when we "right

shouldered" duffle bags (Are you kiddin ?) at the little railroad siding and groped our way through the inky darkness

to find a charpoy for the night and listen to the barking of the jackals outside the bashas.

In rural, laboring India the women are the bread-winners while the men sit by and reap the harvest. Whether puddling

concrete on the runway extension or carrying the red earth in crude wicker baskets atop their heads for fills along

the roadway, they were fascinating to observe (in varying degrees, of course, and to no two persons for quite the

same reason!) The "sari" is an interesting garment.

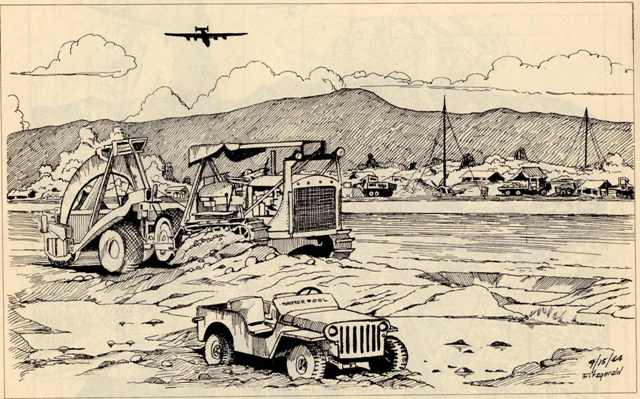

Looking back across the months to Piaradoba we know now that this had been our proving ground. Here lay the task of

completing a 7,500-foot concrete runway and building the aprons and taxiways to support a bomber whose weight and size

were only vaguely known to us. We commenced with Airborne equipment (an Airborne carry-all doesn t make even a

sizeable wheel chock for a B-29). But we began to acquire some knowledge of the working habits of the natives and

learned that the only way to get two shovelfuls of dirt in an allotted place was to engage two natives for the chore.

It all seemed like the enactment of a pageant done in slow motion to better observe the rhythmic movements of the

actors. The inevitable basket was the means of conveyance of everything. Custom is a difficult thing to change, nor

did we try after a few unsuccessful attempts. The incident is told of the officer who brought a half dozen

wheelbarrows onto the job to increase if only slightly, the tempo of the cement haul. The natives filled them and

then, finding the vehicle too heavy for one to carry, two lifted it upon their heads and trudged off to the section

being concreted. Natives were more plentiful than wheelbarrows and so custom won. However heavy equipment soon

supplemented our airborne machinery and construction shifted out of low gear.

We made mistakes; but men who had never driven anything other than the Model "A" Ford the gang used at school or

operated anything more complicated than the two gears of an office building elevator, climbed on to motor graders,

D-8 s, and power shovels, and with the help of a few veteran operators, made quite a showing for themselves. Our

mistakes were not complete liabilities and the success of our work ahead could always be traced to its trial and

error period at Piaradoba. In spite of the dust and almost unbearable heat, soaring to temperatures of 140 degrees,

and often necessitating the use of goggles and respirators to protect the men and flags set up at the corners of

fills and cuts to give them their bearings, the field had landed its first Superfort and there were hardstands to

give parking room for many more, where we struck camp and convoyed over to Kalaikunda. Yes, this was Piaradoba where

the sun often rose like a ball of fire in a lead-hued sky and enterprising GI s talked of constructing fans, and

harnessing some of the multitude of lizards as a course of power to turn them.

There was a change of command too and in April the "Old Man" we have today, Lieutenant Colonel, then Major, John A.

Morrison succeeded Major Frank M. Crittenden, the gentleman from the deep south who saw us through Westover,

Laurinburg-Maxton, and out to India.

But before we ramble farther in this journal only to discover that we ve got a whole "darned" company A.W.O.L.,

we must needs take a spur from the main stem and note the mission and the incumbent trials and tribulations of a part

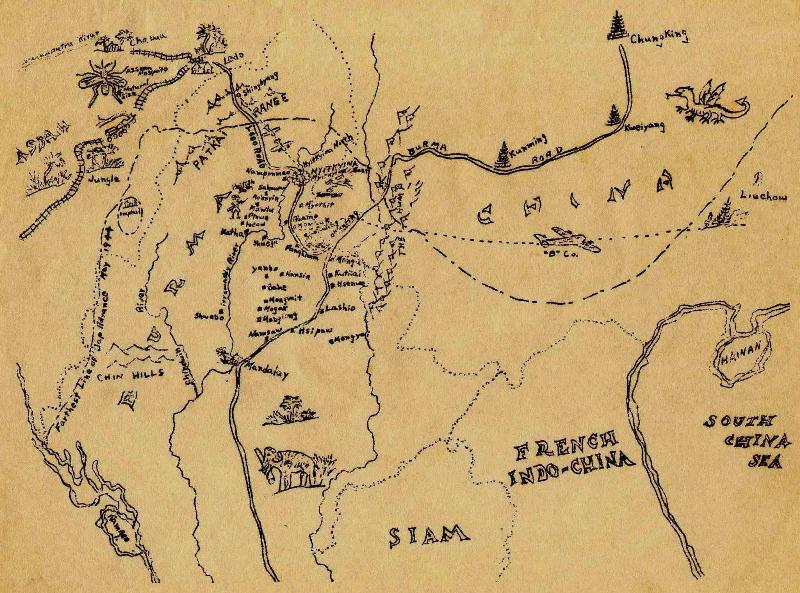

of us at Shingbwiyang, Burma.

We were at Piaradoba hardly long enough to get the kinks from the train ride out of our backs when orders came

directing one company, with medical support, out on a special mission. They were pretty close-mouthed about it at

the time though we had heard some stories that the 900th Airborne Engineer Aviation Company, recipient of some pretty

bad knocks was "taking a break," and we were going up to relieve them. Shingbwiyang is a hell of a long way from

Piaradoba and half-doubting such a destination because of this, we loaded up and riding the rails again we listed to

the high-pitched whistle (what this country needs is a good American train whistle) of the puffing iron ponies of the

Bengal-Assam Railroad, and headed northward into Assam. At Parabatiput, where the Bengal s standard rail ends and

the meter gauge commences, we made a complete change from sow-catcher to caboose lights. American "Caseys" sit at

the throttle from here on up, and judging by the scattered wreckage at some of the curves and sidings, must indeed

have followed to the letter the exploits of America s legendary engineer. Seriously, though, these railroad

battalions have performed miracles of increased tonnage of delivered goods, and more closely scheduled runs over this

only line into Upper Assam.

At a little spot called "Pigeon Hill" (evidently founded by the Americans when they first discovered Assam back in

1942), we were divested or our Pullman Service. Loading onto a seventy vehicle convoy here, approximately eight

miles this side of the Brahmaputra River Crossing at Pandu, we rolled on to complete our journey to Dinjan. Dinjan

nestles among the picturesque tea plantations in the northeast corner of India. Here we inventoried our personnel

and equipment and stood by for further orders.

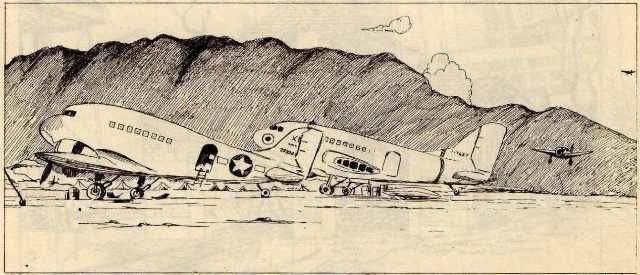

On the 13th of April, with a full Airborne Company Table of Equipment, the first of us flew from Dinjan to

Shingbwiyang in the faithful old C-47 s, light work-horse of the transport command. On the 24th of the month the

last plane loads were over the Patkai Hills and we had the initial stage of a pretty fair area carved out of the

jungle, a half mile from the field, just off the old Combat Road, the trace following subsequently by the Stilwell

Road. The geographical location of Shingbwiyang, relative to its susceptibility to the monsoon rains, is comparable

to the plug in a bathtub back home. Its location is favorable to making it one of the wettest spots in Burman and

during our stay here it proved to be just that. We virtually lived in rubber boots; though this really only gave us

a choice of dampness. Because of the high temperature and humidity prevalent during the monsoons, perspiration

ensued at the slightest exertion, and our feet were constantly wet. With the boots, however, we did manage to keep

most of the mud on the outside. During the period from 24 April to 17 May the sun came out of hiding just three

times. It was impossible to keep clothes dry or to dry them after washing. We finally resorted to using the stoves

in the mess hall. This lent atmosphere and helped to give the mess hall a homey touch (needless to say a pair of

silk stockings and panties to match would have helped even more).

Before the last of our troops were in from Dinjan, maintenance of the strip was turned over to us. This proved a

routine problem of drainage, and repair to soft spots, for the most part. One six-hundred foot soft area near the

fighter dispersal apron was especially troublesome. A constant haul of gravel was necessary to keep it up to grade.

Later we learned from the engineers who built the strip that our trouble spot was the site of a deep gully filled with

logs and brush in order to hasten completion of the runway for the emergency then existent. On May 10th the company

was relieved of maintenance work on the strip and adjacent roads and after consultations of the powers that be, these

consisting of Brigadier General Godfroy, Air Engineer for the theater, Colonel Asensic, and Captain Veccllio, the

initial supervisory officers for this area, plans were complete for the airborne mission which was to usher in the

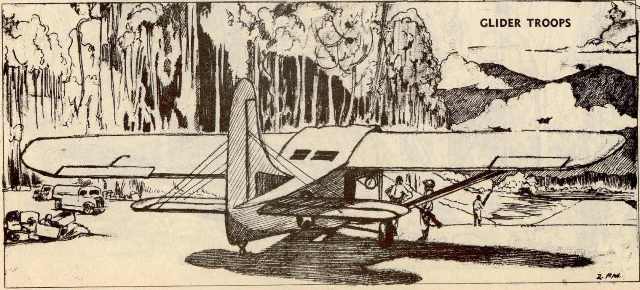

active construction of airfields in North and Central Burma. On 15 May we were alerted and, loading ten gliders with

minimum essentials for thirty troops and a sizeable array of our airborne equipment, we stood by for the takeoff.

At 1700 hours on the 17th, the afternoon of the seizing of the strip at Myitkyina, with newsreel cameramen, war

correspondents, and a scattering of "brass" on hand, our miniature armada cleared the field without mishap. Just

prior to this, two air raid alerts introduced the possibility of Japs, aware of our mission, lurking in the vicinity

for the kill. However this danger never materialized, and under fighter escort, the operation was underway.

Back in India, Kalaikunda was really a carbon copy of Piaradoba, except perhaps for an increase of dust and higher

temperature recordings. A supplemental Table of Equipment assigned us machinery standard to a heavy Aviation Engineer

Battalion and so we began in earnest the double role we were to play until we shed our affiliation with the Airborne

title in March of 1945.

Dovetailing into the immediate need for great support to Company "A" at Myitkyina, our companies "B" and "C," along

with construction and administrative personnel from Headquarters and Service Company, were alerted for air movement

and dispatched to Sookerating, Assam, for briefing an organization for further transport to Myitkyina.

Our sojourn on the heat-swept plains which was Kalaikunda s locale was brief, as indeed was all our work on the very

heavy bomber bases of the Bengal area, and our deportation to the jungles of Burma the commencement of our real

mission in CBI. The main body of Headquarters and Service Company remained behind temporarily to complete the

procurement of heavy equipment and followed along by rail to the "Hump" and Burma jump-off stations at Chabua.

The otherwise noteworthy incidents of that move, from the early morning embarkment at Kharagpur, past the ferry

crossing of the Brahmaputra at Pandu, remembered arguments of barter with the natives along the way and the shower

services provided free of charge by the railroad at any whistle-stop permitting time to shed a pair of pants and duck

under the water hose whose normal function was satisfying the enormous thirst of the locomotives, must be left to

memory without further reference here. We nudged the cows out of the Staging Camp at Chabua, over-run with grass and

in a sad state of disrepair and settled down to the rear echelon functions of support to our line companies up ahead.

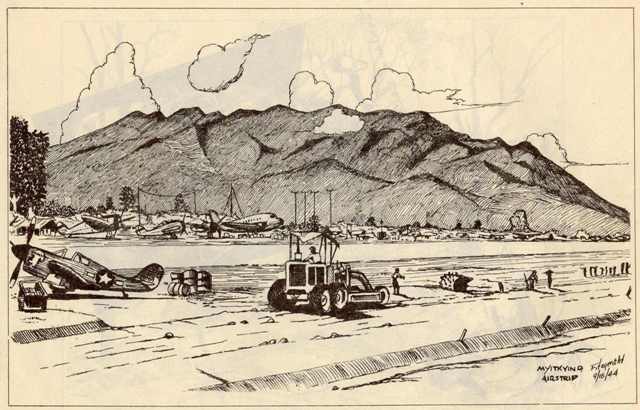

On 17 May 1944, Myitkyina Airfield, in the mountains of North Burman, was occupied by American and Chinese forces.

The story of that occupation, colored by the long trek of the "Marauders" made over the roughest terrain any group of

foot soldiers has ever been obliged to traverse to rout an enemy and coupled with the glider landing of an advance

echelon of Airborne Engineers, coming in in the face of enemy fire to begin work on the field which was to supply our

allied advance through North and Central Burma for months to come, is known to all the world.

That was at the same time our naval forces in the Pacific were hammering closer and closer to the Nip inner defense

circle and the whole tide of the Asiatic and Pacific campaign was turning slowly but surely to seal the doom of

Japanese dreams of an empire of little rising suns. The tide was turning too in Russia and in the air over the

British Channel and over Normandy. The long talked-of and anxiously awaited Second Front was coming any day now.

At home war production gained an unprecedented speed and the Superforts were soon to begin pounding the deep inner

factories and resources of Manchuria and the Jap Home Islands, feeling their way in by way of Rangoon and Singapore

and Bangkok like a huge finger pointing ever closer to the heart of the enemy.

Our part in the Myitkyina siege and occupation began with those thirty men whose ten gliders were cut loose above the

grass covered remains of the old British airstrip northwest of town, abandoned back in 1942 when, in the words of

"Vinegar Joe" Stilwell, "We got a hell of a beating (and) we got chased out of Burma." The task of rebuilding and at

the same time keeping open for traffic "South Strip" as we know it today, was no menial chore. When the advance

echelon dropped in for the mission no one of them would ever have dreamed that in a matter of weeks, as a result of

their initial beachhead which opened the way for a total of three companies and supporting detachments of their

comrades, and the work which followed in the wet days thereafter, that that little band of dirt and gravel some

seventy-five feet wide would be taking a greater flow of traffic than LaGuardia Field, New York.

During the six months which followed the occupation, this field, completely rebuilt and maintained by air supply, was

the axis about which all the activity of north and central Burma rotated. Through Myitkyina came the forces to

complete the occupation of the town and scattered pockets of resistance adjacent, the British 36th Division which

fought down the railroad corridor and across to join the 14th Army, also British, near Lashio, the pincers which

really ended the war in Burma or reduced it to small skirmishes about the areas southward from Mandalay, and through

it were evacuated the 3rd Indian Brigade, the Wingate Forces and a constant flow of wounded. For this same period

all the supplies necessary to subsist and otherwise support these troops was of necessity routed through "South Strip."

Of the ten gliders coming in over the target area in the initial invasion, only the first landed south to north

utilizing the entire runway. Of the remaining nine, all crash-landing from west to east (cross field) and all

smashing into revetments, two came down in Japanese held territory; but the men uninjured, managed to return to our

lines. In spite of the seeming error in approach only four occupants of only one glider were injured to an extent

requiring evacuation, and no supplies or equipment were lost.

Shelling and sniper fire was irregular, though frequent, during those first early days; but gradually abated as the

enemy was forced out in an ever widening perimeter. Our casualties were few and of these none were serious. From

the first day until the fall of Myitkyina town, a period of some seventy-eight days, the battalion was obliged to do

double duty (and that s a conservative statement). Blackout requirements confined engineering activities to the

daylight hours, which unfortunately coincided with the hours of intense traffic and thus it is no exaggeration to say

that the runway was literally rebuilt and maintained under the rolling planes. By night we doubled as Infantry and

were assigned a large area of the necessary perimeter defense. Many of the troops lent a hand in transporting the

wounded and burying the dead. Our battalion surgeon, who crash-landed with the first glider wave the afternoon of

the occupation, joined Colonel Seagrave (of "Burma Surgeon" fame) and helped in the task of caring for the endless

line of casualties, representative of American, British, Chinese, Indian and Chindit forces deployed in the siege

which was progressing toward the town.

Beginning with picks and shovels and our light Airborne equipment (which seemed commensurate to attempting the

drainage of Lake Ontario with a fire hose and a suction pump), we plugged the holes in the runway as fast as the Japs

could make them and somehow managed to make it take shape under new management. After our heavy equipment began

coming in things really looked up. "Cats," "Pans" and Patrol Graders were brought in by C-47 and C-46 over the only

road open in those days, the one we first came in on, at about six thousand feet altitude between a disillusioning

carpet of green jungle and a murky monsoon sky. This equipment was flown in from Chabua and Dinjen in Upper Assam

where our Headquarters Company remained to "cut it up" for air transport. (Incidentally the first such operation of

any worthwhile size successfully undertaken). Progress went ahead by leaps and bounds in spite of the seas of mud

which made us wonder at time whether we were constructing an army base or had somehow contracted to build the thing

for Naval operations, and by late August construction was continuing under relatively peaceful conditions, not because

the Japs were so much unwilling, as unable, to alter the situation. The spasmodic bombing and strafing attacks were

practically at an end and the last Nip had been routed from the Number Nine hole on the golf course in the middle of

town. Though our fox-holes were kept open for unexpected and unsolicited business we rarely went "indoors" any more

and most of the troops had real army cots on which to sleep. (To think that those could be a luxury!)

We were fortunate at Myitkyina, though the few casualties we did have were no less painful or sorrowful because they

were few. We won t soon forget the fellowship we know with those killed or evacuated because of wounds. There are

pages we could write here. Doubtless each of us could ramble on at great length tolling the

darnedest incidents which

for some reason we will remember long after the facts and figures are relegated to the archives o the War Department.

Maybe because they were funny or tragic or pathetic or foolish or perhaps a smattering of all.

For instance, there were the uses to which we put the many colored silk cargo parachutes which were used for supply

dropping during the occupation. Flying over the field in those days you couldn t help but think of a gay colored

carnival back in the old home town, and laugh as you remembered your camouflage training at Engineer school (we didn t

have to live in a fox-hole with a minimum of essential equipment then.) Pup tents are all right for the movies or

even for a few days camping; but they don t hold up too well for an extended stay in two feet of Burma mud. Remember

the grass and brush and how we had the white parachute shrouds strung out through the jungle as a guide line to

"Mrs. Murphy s Rest Home?" Even with the guide line there were few who d bet, without odds anyway, that a chap with

dysentery could make the course in time. (Dysentery is an illness which defies any stop-watch every made!) Remember

how we crowded around the radio each evening at Company supply getting a BBC gander at the outside world and a little

of Tokyo Rose thrown in for contrast and amusement. The pilot light on the dial and the faint glow of an occasional

cupped cigarette were the only signs of light to mingle with the fire flies in the grass on the revetment outside.

About this time too the P-40 boys down on the end of the strip were keeping their ships together with baling wire and

dropping belly tanks of gasoline on the remaining bunkers over at the bend of the river where the enemy still insisted

on dying for "honorable emperor" and the Chinks dug under the railroad to get at them. A story which came back too,

about this time, was the one which centered around the few box cars which our Tenth Air Force bombers and fighters

left right-side-up on the siding at the railroad station. It seems that the Chinks had a handful of Japs cornered in

one of the cars. Darkness fell before they could complete the mopping-up operations and so they crawled into an

adjoining car to await the dawn and to renew the attack. Both parties passed an uneventful night though doubtless

the Japs, greatly outnumbered, suffered more apprehension for the ensuing scrimmage.

We got in on the final kill, too. Some of the boys used to spend the night down on the banks of the Irrawaddy to be

on hand for a shot at the little "Sons of Heaven" who attempted to ship down river behind a bit of floating brush

under cover of the early morning fog.

Stories and jokes about each other there were many; and long years from now, we ll probably chuckle some evening at

the supper table and Junior will stop a forkful of spinach enroute to his mouth (the only thing we ll insist they

leave strictly alone will be Spam) and will pause for the yard sure to follow close on the heels of the chuckle.

"Oh, did I laugh? I was just thinking of the time the sergeant in my tent back at Myitkyina dived into a fox-hold

half filled with water, sans clothing or any preliminary questions. You see, we had a little fellow with us who had

quite a habit of talking in his sleep. It was about the time the Nips were still lobbing over a few shells with the

only gun of any size that they had left. (They shunted it up and down on the railroad and it was quite some time

before our "grass-hoppers" finally detected its position). They were quiet that night but the kid must have been

dreaming about them; along about two in the morning he was mumbling some gibberish which sounded as much like Burmese

as anything else and then, really getting worked up, yelled, "I hear em, fellows! Get for cover!" Well, the sergeant

did. "But, Daddy, did the sergeant wake up the man who was dreaming?" "Did he wake him up!" (We smile here). "Yes,

afterward but eat up Junior. Your supper s getting cold."

And among the stories, too, will be memories of the erstwhile colonel of the Tent Air Force Engineering Section who

was coordinating our work at Myitkyina. We ll always have a warm place for him. Whether we were buck private or

general, he was always his inevitable genial self to us all. He liked to whistle and did no end of it. We didn t

need the top kick s bellow to "hit the deck" in the morning. We know it was high time to be up and about when we

heard the mess kits rattle at the mess hall and heard the colonel "fluting" his day s selection as he came down the

road from his basha along with our colonel. It bucked us up to have a couple of "eagles" in the chow line with us.

He knew the cooks and usually had some enlightening comment about the powdered eggs or the Indian coffee. (It takes

a lot of geniality to enlighten powered eggs). The mess sergeant was embarrassed as hell one rainy day when he asked

a couple of us to move outside of the mess hall to eat (he had reason to, for it was only a lean-to as yet, and it

was hardly fair that two of us should squeeze under shelter at the expense of the rest.) The colonel was getting

settled on a box himself; but he got up and, commenting that he guessed the sergeant meant all of us, betook himself

out into the rain with us. But his "good nature," which was as much a part of his lanky frame as his whistle, was

not an asset in lieu of his thorough efficiency as an officer and an Engineer. Rather, it accentuated it.

Neither is word of him here a detraction from mention of our own more immediate officers; for they ve all found a

spot in our hearts and, in spite of the "bitching" or perhaps even because of it, we ll remember them all as a bunch

about as tops as they come. We all got along pretty well, officers and men alike. (When you get to know a gang as

we had come to know each other, this all comes pretty natural).

From the day the band on the docks at Hampton Roads played us a farewell to Shangri-La we were never really together

as a complete battalion. Always at least one company was out making history on its own. Company "C" had the LSE-2

to themselves coming over and Company "A" left us at Piaradoba to reconnoiter at Shingbwiyang and then spearhead the

engineering activities at "South Strip." So it was also at Myitkyina. By the time our reach echelon, the "Chabua

Commandos," had convoyed over the Patkai Mountains to join us, company "C" was already aboard flatcars on the "jeep

train" enroute to Mawlu, Katha, and points southward in engineering support to the British 36th Division. (The

Railroad Battalion was still at work salvaging enough parts from the rolling stock to put a couple of engines back on

to the Myitkyina-Rangoon Railway, Burma s one and only).

The 36th Division was supplied initially by air-drops as they launched southward from Mogaung whence they had come by

the jeep-powered flatcars from Myitkyina. However, it became increasingly difficult, as the fighting pushed father

down the railroad corridor, to air-drop all of the vital supplies necessary to sustain so large a force in so rapid

an advance. In view of this it was decided that fair-weather strips constructed at various points along the route of

advance would facilitate handling the greater quantity of supplies and aid immeasurably in the evacuation of the

wounded. The difficulties encountered in such an undertaking would be numerous; but the strategy was sound and

ultimately proved extremely successful.

Company "C" of our battalion was delegated this task and an advance detachment of approximately one platoon left

immediately by jeep-train down the corridor through Mogaung, Sahmaw, Hopin and Mahmyin, finally arriving at Mawlu,

where the first temporary strips was cut out. We set to work at once with the few pieces of equipment brought along

and had a field ready for transport landing in the record time of two working days. The strip served remarkably well

despite the fact that it was simply graded out of the rice paddies predominant in this section of Burma. We were in

constant danger of ground fire from small groups of the enemy infiltrating through the lines at night or from

stragglers caught behind the line of fighting. Danger from air attack was comparatively light though on one occasion

soon after the balance of our company had joined us, medium bombers swept in over the field at night while men were

readying it for the next day s traffic. Luckily no one was injured and operations continued with only slight

interruption.

Following closely on the heels of the British ground forces, a detachment of us went forward again from here to

construct a liaison strip at Pinwe. After the completion of the strip at Pinwe the rate of advance had already made

necessary the construction still another support field at Indaw West, about twenty miles south of Pinwe and Naba

Junction.

Lest the reader ponder, without satisfaction, such speed in construction, a word of explanation is needed. The series

of fair-weather airstrips which we were building were useful only as intended; that is, for the close support of

combat forces pushing forward. When the first rains of the monsoons came they revert back to the marshy rice lands

from which they are formed. Most of the detail of construction lies in removing the miniature levees which divide the

acreage into hundreds of tiny fields. Those levees are so constructed to "step" the water down from the hills, taking

advantage of the slightest grades in such a manner that one small stream may flood acres for early planting before the

seasonal rains come and they provide a means of holding and regulating the water during the growing months of their

two staple crops rice and sugar cane. At the time of our advance, during the dry winter months, this earth, which

is a sea of mud during the rest of the year, was caked hard. With the "cradle-knolls" levees, and other small rises

cut away and the brush cleared, a relatively suitable landing field is made in a minimum of time which will stand up

under quite strenuous conditions for the brief period used before the offensive moves beyond range of its effectiveness.

Such strips were Mawlu and Pinwe. A detachment again went forward to undertake the Indaw job. Here we had a unit of

British Infantry as perimeter guard around the area of construction, as the work was actually being done in advance of

the existing British lines. Danger of encountering rear-guard action patrols throughout the vicinity intensified the

incentive to finish the job in the quickest possible time. (It may be further stated here that such was done). Now

supplies could again be brought in by air so that the enemy might not be allowed any respite whatsoever from the

formidable pushing of the 36th Division. Continuing the rapid advance, British units soon occupied the town of Katha

situated on the banks of the Irrawaddy approximately twenty-five miles southeast of Indaw. It was decided that an

airstrip here would prove of strategic value. Hence our detachment at Indaw and the rest of us moved immediately to

the location of the proposed runway just out of Katha. In the three days just prior to Christmas the field was made

ready for transport landing, a road improved linking the town with the strip and an area for the Company completed.

"Created we this in three days and on the fourth rested."

Our story would not be complete without some mention of the intra-regiment radio network. Because of the ever-widening

dispersal of the battalions and scattered companies and construction platoons necessary to execute the requirements for

control of an area rapidly embracing all of Central Burma, this network proved of no little importance in maintaining

contact with our headquarters in the Battalion and in the Regiment. Construction delays were kept at an absolute

minimum and personnel matters were expedited as a result of the rapid ordering of spare parts, submittal of strength

reports and other necessary administrative and supply matters through the facilities of this communications set-up.

The British, laying by at Katha over the holidays for a far briefer period, and with better fortune, than did Howe at

Trenton in 76, were still not to be denied in their drive southward. The Katha field, originally planned for

all-weather finish, had already fallen too far to the rear to pay dividends as a "black-top" project, and on 5 January

we dispatched another detachment forward to Yanbo, some fifty miles below Katha and across the Irrawaddy. The river

crossing was accomplished by means of four one-ton pontoon boats brought down river from Myitkyina. Powered by an

equal number of heavy duty outboard motors, all equipment for the mission was ferried over in this manner. The Yanbo

field opened on the 12th, we continued leap-frogging detachments forward to keep pace with the combat troops, the next

move being to Bahe via thirty miles of jungle trail. This strip proved to be the determining factor in finally forcing

a crossing of the Shweli River, here where the Infantry had run up against a well-entrenched enemy on the opposite

bank defending the village of Myitson. Once again a rice-paddy air terminal took a terrific pounding from heavy air

traffic bringing in ammunition, rations, and Gurkha reinforcements. It was here that the main body of our company

caught up with us, this move being under way when we were ordered back to join the Battalion at Mu-So near the

Ledo-Burma Road junction where construction on an all-weather field was underway. Leaving a detachment of some

seventeen men in further support to the 36th, the balance of us cut our way across to Lashio, and thence up the old

Burma Road to the junction and to Mu-So.

To remain a little longer with this platoon, in our narrative: After forcing the crossing at Bahe, our detachment

ferrying the troops across with the ten-ton pontoon boats brought down the Irrawaddy from Katha and up the Shweli, a

considerable distance, by a platoon officer turned fresh-water admiral and a small group of versatile GI seamen,

continued opposition from the securely entrenched forces along the Myitson-Mongmit road halted the advance at the

outskirts of the village. Executing the only strategic alternative to the road block, we were supplied a Gurkha guard

and in three days cut a seventeen mile road around the mountain rising between the two villages, permitting a surprise

maneuver to a shelling position overlooking Mongmit. Completing mop-ups in this sector, fighting reached the old Burma

Road below Lashio by late March. Our detachment completed two more supply and evacuation fields in support of this;

one at Monglong and the other at Namsaw near the junction of South way corridor and the road above Mandalay. Thus

ended a four-hundred mile trek through some of the most impassable jungle in Burma, frequently requiring the

construction of roads and bridges to reach the runway sites and constantly presenting supply and engineering problems

requiring ingenious improvisation to meet the demands of a rapidly moving offensive. The venture was unmistakably hailed

a mission accomplished with outstanding success and contributed greatly to an already rapidly climbing record for the

Battalion. A record which somehow was fated never to be rewarded with the citations and awards normally consistent

with such work. We consoled ourselves with the realization that ribbons and decorations really do not matter much,

that the important thing is the job well done; but non-the-less, like the lad confident of a Christmas present and

finding the tree empty, we too quite obviously knew disappointment.

In taking this circumvention just concluded we have by-passed an accounting of the main body of the Battalion which we

left at the outset of our mission with the 36th Division. In further narrating our history, which seems to have

become more and more difficult to tie into one travelogue, we can only go back to the period in late November, some

weeks after the departure of Company "C," and follow through with a detachment of Company "B" on a similar mission,

also southward into Central Burma.

Toward the end of November the Mars Task Force and Chinese units on the east flank of this huge pincers around Central

Burma, had pushed on from Kaza, where the monsoons had held them immobile, to a position threatening Bhamo. Here a

need for support fields similar to that in the "Corridor" developed and a detachment of out Company "B," flying by L-1,

set down at Momauk, just east of Bhamo, where the "Chinks" had roughly converted the rice paddies to land liaison

craft, and, working, altogether with hand tools, we enlarged the field for cargo use. In chess board language, this

was the pawn moved forward to free a more powerful piece for action, and Airborne equipment was brought in to Momauk.

This was little more than accomplished when we were able to crowd hard on the heels of the combat troops to gain

access to the existing field in Bhamo. Moving up while the strip was still under light fire and in position for

shelling from the town, we put to good use our recently acquired equipment to fill the numerous ditches dug by the

Nips to deny the field to Allied operations. Further conversion of the runway to take heavy traffic required the

work of a sizable battalion with standard equipment and most needs await the fall of the Bhamo town before transport

planes could land with any degree of safety. Bhamo had necessitated a siege similar to that which finally subdued

Myitkyina and it wasn t until 18 December that hostilities ceased. In the meantime a portion of our detachment had

completed a fair-weather strip southwest of the main field, which was in use by 5 December, though even her sporadic

artillery fire limited consistent use until after the two capitulated.

The main body of the Northern Combat Command Forces had pushed on some fifty miles south and southeast into the Tenkwa

area during this same period and a field capable of taking C-46 traffic was urgently needed. Accordingly the balance

of our detachment, which had been reinforced while at Momauk was tagged and preceded by L-1 and L-5 to a small

"grasshopper" strip near Nansin. They negotiated the remaining four miles to the site of construction on foot.

After the arrival of an airborne "bulldozer," the "6x6" which had transported it and one jeep by road by the Bhamo

area, we made quite good progress and our remaining personnel were moved in from Momauk. While there were no banners

waving and not even a bottle of beer to commemorate the event, this two vehicle convoy was the first such Allied

traffic over the newly won road into this part of Burma. An entire Chinese division was evacuated from this cow

pasture runway to fill a critical need up front in China and shortly thereafter, with the continued advance of the

"Marsmen" we followed through to Loi Wing, location of an old Curtis Assembly Plant, on to Panghkam and thence to

Mu-Se, building the necessary support fields enroute. Having now increased our pool of equipment to include a motor

patrol, a "D-7 dozer" and carryall, the work of converting the paddies at Mu-Se was a relatively small detail.

Though a small unit continued temporarily on as far as Kutkai, it was here that we were taken back aboard the mother

ship, as our Battalion S-3 section had come in to begin layout work for an all-weather field on the other side of the

village.

And so it was after the turn of another year, in early February, that those of us not already at advanced stations

down in Central Burma, made preparations to depart from Myitkyina.

The enormous traffic which had been handled by "Myitkyina South", as it was now called, was partially shared with

three neighboring fields, all of which we had had a hand in building. The pipe line was into Myitkyina and well

beyond. The big C-87 "Flying Oil Tankers" (cargo version of the Liberator) were running a huge bucket brigade on to

China. We were talking about the Khai women of Shillong and our furlough exploits at Calcutta, where, in turn, we

were taking time out for the sorely needed rests and meeting the bemedaled heroes of that bastion of supply and of

Belhi and Agra - heroes whose greatest gripe was a shortage of ice for coca cola (or so we pictured it, feeling sorry

for ourselves) and "bitching" because some lieutenant won the Bronze Star Meal for decorating the Officers Club back

there; while our own officers and men waded hip deep in the mud of pagan land, "somewhere east of Suez on the road

from Mandalay" "browned off" Yes, we figure we were, a little anyway; but, in reflection now, too busy building

"jump-offs" to Japan to smolder long.

On 6 February, the C-47 bringing part of our S-3 Section into Mu-Se to survey lines for our job there, overshot the

fair-weather field, crashed into the bamboo hedging the south end of the strip, and burned two of our own Medics,

serving with the Company "B" detachment at the time, along with other personnel in the vicinity, pulled to safety as

many of the occupants as was possible before the flames became too intense for further rescue. All the crew members

were killed and three of our own men narrowly escaped and only squeezed through as a result of efficient hospital

evacuation service.

This fair-weather strip, constructed in the only naturally level spot in the valley floor by our Company "B"

detachment, had its approach from over the Shweli River and ended abruptly some four thousand feet away where the

foothills crowded in. It was so situated as to be in the path of treacherous cross-winds existent when only a breeze

was blowing and became the jinx-field for those flying jockeys of Combat Cargo (incidentally an organization which

deserves an overflowing share of credit for the success of the Burma Campaign) who had to make the stop to unload

personnel, supplies, and pipe for the petroleum Engineers laying the "big inch" to Kunming. Another six or eight

planes were to crash here before we completed the large runway in the hills above the village.

Another of our construction men was killed by snipers while on reconnaissance past a roadblock near Kutkai. These

were sobering misfortunes which precluded our work at Mu-So. Before long though the only acreage in all that rolling

countryside which even looked as though it had the potentials of an airfield, began to have all the earmarks of a good

one. Pushing hills into valleys, the D-8 s, D-7 s, pans graders and trucks rumbled through and around the clock

schedule. It was higher and cooler here than any of our previous stations. The half-buried bodies of Chinese and

Japanese soldiers up on "Bloody Nose Ridge" had hardly begun to decompose when we began work at Mu-So; but the war

was soon to move on far below us, the road and the pipeline with it and already continuance of the field seemed no

longer a strategic necessity.

Indeed, looking back now, this period at Mu-Se and Lashio was the beginning of the turning point for us Burma This

was in March when Company "C" was enroute back to join us from Bahe and Company "A" had moved on down to Lashio.

We, of Company "A", began our move on 18 February when a picked number of men, including surveyors and operators, set

out for Kutkai, about sixty-five miles south and east and well into the forward area of the fighting then progressing

in the drive on Lashio. With our small convoy of one tournapull, two "D-7 s, with pans, a patrol grader, one truck

and a jeep, we reached Kutkai, one mile behind the front lines, late in the afternoon of the 19th. Tanks lined the

road and Chinese troops sprawled on and amongst them awaiting word to move up. Artillery could be heard pounding out

the deep throated notes of the symphony of war and we could watch our fighter-craft sweep in over the target area in

strafing runs. Part of our detachment dug us in while the remaining numbers pitched camp and serviced the equipment

for commencement of activities after evening chow.

Despite a large "cut" necessary at one end of the side and a hundred and one contrivances the enemy had rigged to

obstruct the area, we made good progress and by the 23rd of the month the runway itself was operational. Not all the

wreckage in the vicinity was useless and we managed to salvage parts of enemy equipment for use here and along the

way; including an old Jap steam roller which, though the boiler had been converted into a giant sieve by machine gun

fire, with the addition of a tongue made a handy piece of machinery for towing with a "cat." After Myitkyina and in

monsoon heat and high humidity, the cold at even this medium altitude worked right through us. During several early

mornings we found ice in our helmet wash basins.

When the tally was all in and the Burma campaign moved into the sunset of any further major battles, this fair-weather

runway at Kutkai recorded an entailment of the most extensive earthmoving operations to ready it for transport landings,

of any of the many such fields we had scraped out of the jungles and paddies of Central Burma. But to credit Company

"A" alone with this field is to overlook the spearhead of the operation which was undertaken by a part of our Company

"B" detachment moving on down in support of the "Marsmen" and "Chinks" even as the fair-weather strip at the foot of

Mu-Se village was being completed. They were recalled to reinforce the work crews at Mu-Se only after Company "A"

arrived to relieve them.

Toward the end of this period at Kutkai a detail of two Company "A" operators with a patrol grader cleared a liaison

strip at Hsenwl a few miles south of Kutkai and immediately adjacent to the fighting lines. The site of this grass

plot was located two miles off the main road and as it happened the connecting road was quite heavily mined, unknown

to the operators as no warnings had as yet been posted. The mission was completed without mishap however and the

detail returned late the same day.

Next orders were to proceed to Lashio, in further support of the drive now gathering momentum and pushed just beyond

that town of "AVG" and Burma Road fame. The road down was in poor condition, (as roads subjected to war treatment

are because the retreating Japs and our own bombers had blown all bridges.) Trucks crossed on makeshift bridges and

all our heavy equipment forded the streams.

By 12 March our entire company had joined us at Lashio. A fair-weather strip had been completed paralleling the

north-south runway, this temporary field to serve until damage inflicted on the permanent runways could be rectified

and the field made all-weather and work on the permanent installations was well under way. Both runways were in

serious condition from Japanese attempts to fool our forces by cutting skillfully concealed ditches across the runway

and from the intense working over our own Tenth Air Force had given the locality. Three-quarter inch cables had been

stretched across at various intervals approximately six feet off the ground. Adding to the obstacle course already

created by the cross ditches staggered fifty feet apart the entire length of the North-South runway and covered with

sheet metal and a thin coating of the native surfacing material to give the appearance of an intact runway.

Scattered shells, plane wreckage and barbed wire entanglements added to the work necessary to ready the old base for

business under Allied management. Evidence of quite an array of Nip aircraft was existent, including one heavy bomber,

numerous small ships and two old AVG P-40 s all totally destroyed.

As side dishes to the main platter at Lashio, small contingents readied two additional fair-weather strips, in March,

one at Hsipaw, and the other at Mongyi, in further supply and evacuation support to combat units driving on Mandalay.

Due to the rapid execution of the war in Burma plans for completing the East-West runway at Lashio were discontinued

and by late June the North-South strip had been surfaced and was operational, a control tower built, taxiways and

aprons completed. The fighting had moved on below Mandalay, petering out as it moved southward. The Japs, cut off

from all support and without air cover were rapidly being exterminated. A large contingent of Kachins, two divisions

of Chinese and a sizeable her of mules were flown out of Lashio during our final days there before leaving the area

in mid-July to return to the Battalion now moved back to Bhamo.

As at Myitkyina, down the Corridor and at the siege of Bhamo, at Lashio too there are a multitude of rich experiences,

humorous and serious incidents which must in passing be left to the memory of the reader or told him by the chap who

loaned this story. The temples, old fortifications, and wrecked evidences of a long and colorful history of this

town which Kipling must have known well in days more prosperous than during our sojourn here, will long be remembered

along with the stories lived amongst them. Approached abruptly though, some of us, in recalling this town, may, in

answering your query about it; remark, "That place? Oh, yes, that s where the Colonel picked up his damned Japanese

ice-plant!" But this too is a legend of its own and must for sake of brevity be precluded from this sketch-book.

Suffice it to say that the plant referred to has been lugged over some five-hundred miles of Burma and Stilwell Road

unloaded, partially put together, broken down and hauled further until it has become an obsession to make it turn out

at least a cup of cold water. At this writing, coming into fruition at last, though all of the Japanese writing on

the valves, tanks and couplings has not been deciphered, the Assam Branch of "Tokyo Ice and Coal Co." is open for

business and is dispensing ice with the precision of a cigarette machine.

Back at Mu-Se some 358,000 cubic yards of earth had been cut from the hills and dumped into the valleys to level a

five-thousand foot runway here amongst the mountains overlooking the Shweli River. This was nearing completion when

a half of the big news we and the rest of the "Allied World" had worked and waited for so long, broke around the globe.

Germany had surrendered! "Two down and one to go" was the count, and the "one to go" would get unlimited pressure

from here out. Despite the realization that here so near the end of the world s longest supply line, conservation of

goods in hand was Standard Operating Procedure, ack-ack units about the field felt the need of some commemoration of

the event and expended a few rounds of ammunition to etch the sky in a criss-cross pattern of tracer fire. It was a

feeble comparison to the gigantic Fourth of July displays back home; yet no celebration had ever meant more and none

of us could quite untangle the emotions of relief, gratitude and happiness inside us. It didn t matter particularly

whether they were untangled; for we did know that this was half of it; though a long road might yet lie ahead. And

too there were few of us indeed who did not make the wish, "If only President Roosevelt could have lived to see it."

He could not; for on April 12, while our work here and at Lashio was keeping pace with the success of our cause

throughout the world President Roosevelt passed on, leaving the Chart-Room in command of Harry Truman, and was not to

see from a vantage point on earth the victory he had worked so nobly to help achieve.

Events moved forward at baffling speed, changing the face of the earth and weighing the momentous decisions of

democracy versus Fascism, God versus theism, and it seemed now that the scales were surely inclined in favor of the

freedom-loving peoples of the world.

The "GI" world had grown "point minded" now and conversations not inclusive of this were considered inexcusably

irrelevant and of no particular value to anyone! Thus began the "big sweat" of fluctuating scores and eligibility of

discharge.

It was here at Mu-Se too, on March 1, and during March and April, that our organization underwent a "facial" emerging

sans the Airborne title and incorporating the personnel of the old 900th Airborne Engineer Aviation Company,

inactivated as Airborne, as were we, and merged with us to build, less one company, a standard Engineer Aviation

Battalion.

They brought with them a colorful history of their own, which includes record of the only consistently active glider

operations in the India-Burma Theater. Those men were the veterans of the "Broadway," "Piccadilly" and "Clydeside"

missions and an impressive list of other jobs begun six months before we came out east to add our lot. By way of

orientation a few notes should give us some inkling of their exploits before we knew them as part of our own.

At Westover Field back in February 1943, Company "C" of the 877th Airborne Engineer Aviation Battalion, older brother

by one month of the 879th Battalion of the same name, was, after three months of paternal care (and constant shuffle

of Company Commanders and Top Kicks) pushed off the family doorstep and left to forage for itself in a vast and

incomprehensible army. Yes, that was us. We were made an independent unit for purposes of experimentation and named

the 900th Airborne Engineer Aviation Company.

A "certified true copy" of most any of the Engineer unit training programs, with minor alterations, will give you a

reasonably accurate idea of our first weeks as the 900th. In complete understanding however special emphasis should

be placed on that portion with any GI will explain to you if you quote for him the key words, "Double time, March!"

(and after the first quarter-mile, "Sergeant, take over"). There was a nineteen day "binge" in New York City and

then (pardon the poetry) our training completed and finances depleted, we embarked for India on July 10.

After thirty-three days, thirty feet under (below deck) we survived, with the assistance of stolen "C" rations, a

rather uneventful journey via the Atlantic around Cape Town and up to Bombay. With delays cut to a minimum, we were

railroaded to Leo and out of this Northern Assam terminus, began our first Airborne mission, (on foot, 150 miles over

the old "Refugee Trail" on which traffic came from the other way back in 1942). Seven days of this and we stopped in

the mountains near Tagap to break ground for our first construction job in foreign soil. We broke it with a British

pick and shovel and a little "TNT", all of which were air dropped. Life was as simple as the tools with which we

worked. Each man was allotted a morning cup of water. For coffee? Well, if there was any left. It also had to

suffice for bathing, shaving and for brushing your "uppers and lowers". Surveying equipment consisted of a bamboo

level, a bamboo rod and a six foot steel tape. (Even old Robin Crusoe would have marveled).

After a few weeks, our task completed, we hit the trail again, for a place fifteen miles beyond Shingbwiyang. Here

our principle deployment was a twenty-four hour guard around Dr. Seagrave s Hospital, located here far north of his

normal habitat of missionary days. Some of the fellows assisted him in his work, holding flashlights while he

operated, and otherwise serving useful purposes. By way of diversion and entertainment, the boys aired a nightly

make-believe radio program, sponsored by "Ritter s Beans" and beamed on a Crosley rating of 120 Kilocycles. All

supplies were air-dropped and we were assigned the Quartermaster duties and became custodians of the mess shack.

After weeks, we were forced back to Shingbwiyang from our advanced position and began construction of a dry-weather

strip with the "Airborne" equipment we had used at Tagap. We were at work here about a week when the news reached us

of the race between the Ledo Road Engineers and the Air Corps to be first in this jungle village. With last minute

help from Chinese soldiers, we readied the strip and the first plane landed on Christmas Day, just two days ahead of

the loading truck of the Road Engineers. Our assigned T E equipment was flown in and we began conversion of the

strip to an all-weather field. It was here too that we adopted our mascot, "Mike." He came to us as a half-starved,

chain-smoking Naga youngster and remained with us throughout our journey. All "chipped in" and, depositing to the

credit of one of the fellows in our company, we managed a sizeable sum whereby he is presently at a Catholic school

in Shillong, India.

In February 1944, we were flown to join Colonel Cochran s First Air Commando Group. Our first mission under this

command was in the nature of a training operation, an assimilated glider mission to Tamu, Burma, in the Imphal Valley,

where we succeeded in our assigned task of constructing a fair-weather cargo field and an "L" strip well under our

allotted time for accomplishment. Late in February we were moved to Lalaghat, India, to begin preparations for the

Airborne Invasion of Burma. Preparations involved glider loading and landing operations and allied training