|

MY LIFE AS A G.I. JOE

IN WORLD WAR II

by Thomas Ray Foltz

I turned 18 in the summer of '42. With that birthday, I was obligated by the SelectiveService Act to register with my local draft board in Fort Wayne, Indiana. Since December 7, 1941, our country had been embroiled in a World War with Japan. Soon after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, war was declared on Germany and Italy.

I was inducted and sworn into the U.S. Army on March 10, 1943 at the Toledo, OhioArmory and entered active service at Camp Perry, Ohio on March 17. This Army Reception Center was located on the south shore of Lake Erie, east of Toledo, near Port Clinton. That year winter on the shore of Lake Erie was miserable.

I was transported there in a bus loaded with other men from my hometown. Fort Wayne. The Reception Center issued me a range of G.I. (Government Issue) uniforms and basic personal items and given immunization shots for a multitude of diseases. To determine what I might best be suited for, I took a battery of IQ and aptitude tests. Those results along with my "civilian" skills indicated that my niche was the Corps of Army Engineers.

The day of departure from Camp Perry came and I boarded a troop train. The shades were drawn on all the cars so we did not know where the train was going. Speculation on our final destination was the main topic of conversation.

Within 24 hours, we detrained at Camp Claiborne, 15 miles southwest of Alexandria, Louisiana. Camp Claiborne was a huge Army Engineer Unit Training Center (E.U.T.C.) for railroaders, petroleum pipeliners, combat engineers and other categories of engineers required by the Army. I spent 12 months at Camp Claiborne. I was assigned to an Army Engineer Company for six weeks of basic training. My group was known as Headquartersand Headquarters Company Communications Zone #2 (C.Z. #2), Engineer Unit Training Center. Before anyone had been tapped for the company bugler post, I asked my Mom to send my cornet from home. I got the assignment! At first, the post lookedlike a good deal as I would not pull guard duty, K.P., etc. However, I woke early to blow the bugle for Reveille,performed various calls throughout the day and finally blew Taps around 11 p.m. This duty was performed daily. After 50 years, I don't remember if Sunday was considered a day off or not.

As Claiborne was only a temporary training camp, the vast majority of G.I.'s lived in temporary tarpaper-covered huts with a door near each end of the front of the building. A modest-sized, coal-fired stove stood in the center of the shack. This had to be fed by the G.I.'s who were assigned that duty.

During Basic Training, surprise inspections of the barracks by the inspecting officer orSergeant could occur at any time. Barrack mates were responsible for keeping the place white-glove clean. Laxness in general cleanliness by any individual could cause all his barracks-mates to suffer the consequences of that infraction. Regulations called for the army blanket that covered the bed to be tightly drawn so that a quarter dropped on the bed would bounce a certain distance. If it didn't bounce high enough, the G.I. received a demerit. A demerit meant a loss privileges for bad conduct or failure to observe regulations or orders. It could also mean extra KP duty, guard duty, or confinement to company grounds, even the dreaded no weekend pass!

A common practical joke was short-sheeting a G.I.'s bed. Refolding the sheet so it wasdoubled over. the bed looked the same. However, when the tired G.I. hopped into bed that night, he could only get his feet in half way. This predicament, while funny to those who pulled the joke, was not so for the victim. If he was unable to rearrange his bed and get back in the sack before being caught by the Officer of the Day (and that meant fully reclined during the bed check and in his underwear) he received a demerit.

Fred Jeude, from Evansville, Indiana and I became buddies since we bunked in thesame old tarpaper-covered shack. We corresponded by V-mail during the war as Fred went into a Heavy Equipment

|

Each company bugler pulled a one-week duty at the Regimental Headquarters Flagpole for raising and lowering the Colors (flag). When my turn came, I slipped up one afternoon and got there too late. The flag was already being lowered. I was dressed down proper in the Provost Marshal's office. My 1st Sgt. must have spoken on my behalf because the reprimand was much lighter than I expected. Memory fails when trying to recall mypunishment. However I was probably restricted to the company area or received extra duty for several days.

At the end of our basic training our group, C.Z. #2 was deactivated. We were assignedto the E.U.T.C. Regimental Headquarters, where we were scattered about in various companies of excess army engineers.

Some time in March, 1944, my old 1st Sgt. Harry Berman asked me and two other men if we would sign up as replacements to fill out the roster of required personnel preparing to go overseas. I knew some of the G.I.'s in that company and I realized if I didn't go with them, Uncle Sam would ship me out shortly as D-Day, the invasion of Europe, was on the horizon.

I made a good choice, but didn't know it at the time. The next few weeks were spentfulfilling requirements for overseas duty with my new company, 789 Engineer Petroleum Distribution Company (E.P.D. Co.). We left Camp Claiborne in mid-April, 1944. Again we had no idea where we were headed. However, we knew we would learn soon enough what the Army had in store for us. The train rolled north, then east, moving throughKentucky and arriving at Newport News, Virginia. Camp Patrick Henry was the staging area for our port of embarkation.

While there, all final processing was accomplished and we learned how to abandon ship. Hanging from a wooden tower the height of a ship's top deck was a rope ladder similar to that used on a troop ship. We climbed up to the platform and then would quickly descend to ground level on the rope ladder.

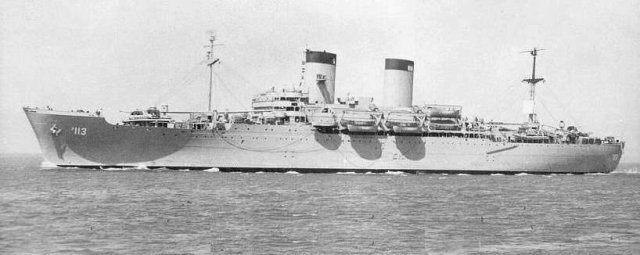

We left the P.O.E. (Port of Embarkation) on April 22, 1944. Fortunately the 789 E.P.D.pulled M.P. (Military Police) duty aboard the U.S.S. General Henry W. Butner. Since we had M.P. duty day and night, we got three meals each day. Most of the other men only received two meals. This was a nice benefit and to top it off, we spent more time topside in the fresh air when we pulled duty on the open deck.

Life on a troopship at sea is quite an experience. For most of the time, it was a hot,stuffy, cramped and monotonous existence. The ship had several decks which were sectioned off into compartments.

|

Time was passed by reading, writing letters and diaries, playing Euchre, playing craps(a dice gambling game), and maintaining our gear (such as sewing buttons on our uniforms and cleaning our mess kit and weapon so they could pass inspection at any time).

The "head" (shower, sink and toilet compartment) that I normally used was under a huge artillery-type gun with a 5" diameter barrel. We never knew when it might fire either for target practice or at an enemy submarine. One day that gun was fired with a tremendous boom. Boy, did that head clear out fast!

Our showers used cold, salty seawater. This daily aggravation required a special saltwater soap. The salt water created problems in the mess hall too. For example many of the mess kits were galvanized steel which corroded if washed in the salt water used in the head. To avoid this problem G.I.'s had to immediately clean their kit in the G.I. mess cans - huge garbage cans with soapy water and then clear water for rinsing. Needless to say the water in the cans would get pretty grungy.

Eating in the mess hall was unique. The ship's cooks would dump the "food" in our kitand we would stand while eating at a long stainless steel table that had a rolled edge on all sides to keep the mess kits from sliding off to the deck. In heavy seas, the ship rolled and pitched as we tried to eat. Under these conditions, we might not have any appetite. If we did eat, we might heave it up shortly.

The ship had a capacity of 5,261 personnel and could travel at a speed of 30 knots (inNavy language). We still did not know where we were headed as we sailed out into the Atlantic Ocean alone.

Cape Town, South Africa was the first stop on the voyage so we deduced that Europe was not our destination. At Cape Town most of the G.I.'s went ashore to see the sights. Unfortunately, I pulled M.P. duty at a loading hatch when we docked. By the time I was relieved and got ready to go ashore, it was dusk. The city sure looked beautiful. I had never seen an exotic place like this. The homes and buildings had cream colored exteriors and the roofs seemed to be made of red clay tiles. The effect was breathtaking as they clustered up thesteep hillsides of the 2,000-foot Table Mountain. Some G.I.'s were quite tipsy returning to the ship and a few were AWOL (Absent without Leave) as the ship sailed.

The Cape of Good Hope at the tip of South Africa is one of the most turbulent stretchesof water around. Under rough conditions, a G.I. was pretty much confined to his bunk. We did not roam about our compartment except to hit the head, eat at mess call or when our outfit was allowed a few hours topside.

Seasickness on a crowded ship is very unpleasant for both those who were sick and theG.I.'s who had to be near them. Very few escaped this problem. I found that if I ate even a little at each mess call it made a big difference. I don't recall being affected with a bad episode of seasickness.

Occasionally the sea was so calm, it was like floating on a mirror. Ironically we weremore uneasy during these calms, because submarines gained tremendous visibility when the water was smooth. Most of the time the seas were rough enough that the ship would roll from side to side and when plowing into waves, it wouldpitch up and down, bow to stern (front to rear).

There were moments that broke the dull monotony of life at sea. One night I was dozing ona G.I. garbage can when the ship began rolling sideways. I awoke to find myself and the garbage can sliding down a narrow passage between the bunks!

A time-honored ritual for crossing the Equator was a dunking in front of King Neptune, the god of the seas, A fully loaded troopship had too many people to dunk each individual, so the vast majority of us, including me, received a mimeographed Shellback Scroll from Davy Jones.

Our troopship actually crossed the equator in the Atlantic Ocean and also in the IndianOcean on our journey to Bombay. When I returned to the U.S. on the General Hodges, I came within 5 of crossing the Equator for a third time.

The Butner made a short stop at Durban, South Africa on the Indian Ocean side. Only authorized personnel were allowed topside there. I don't know what secret activities were carried out at that stop.

May 25, 1944, the General Butner sailed into the harbor at Bombay, India. Those ofus topside saw a scene of destruction. We did not know what had happened, but assumed the Japs had wreaked havoc there. Forty years later I learned the truth from an article in the newspaper. Just one month before our ship docked,a fire aboard the Fort Stikine, a freighter loaded with munitions, blew the ship to smithereens. It also devastated Bombay for several miles inland even though the ship was anchored well out from the docks. Three gold barswere listed on the ship's manifest. They were never reported as being found.

We disembarked the following day. The minute we left the dock area, the smells and soundsof this foreign land simply overpowered us. The crush of humanity, overwhelming poverty and grime, the squalor and appalling smells of the everyday living conditions these people endured engulfed us. We had never experienced anything like this in our lives. Such would soon become commonplace for us.

We boarded a train for the rail Journey from Bombay to Calcutta. The trip, a distance ofperhaps 800 miles across mountains, plains, desert and into the steamy Bengal Province in Eastern India, took five days and nights. We passed through small, indescribably filthy villages and large cities.

The broad gauge (rails were 60 inches apart) British-built steam locomotives had anear-piercing, high-pitched single whistle. The interior of the spartan cars consisted of wooden benches. We sat and

|

As we plodded through the countryside, the train stopped and we lined up outside foreach mess call. Eating outside, we were warned to keep our canteen and mess kit covered or else lose them to diving birds, known as kites, that would swoop down and steal any unprotected lightweight equipment, including a loaded mess kit.

Ill-kept, undernourished Indians (in saris, dhotis and even nude) crowded all the railplatforms. Many of them either sold trinkets or begged for food or money. Sleeping mats were spread out everywhere on the outside platforms and even inside the rail stations. For some of the Indians, the platforms were their home. They ate, slept, even died there. Others were traveling with all their worldly possessions. Imagine the bedlam as they spoke in several different dialects (languages) that prevail throughout India. It was an incredible babble of noise and commotion!

We finally arrived at the Howrah Railroad Station, a cavernous train shed and buildingin Calcutta. The 789 E.P.D. loaded men and equipment into 6x6 trucks. We rode into and then out of Calcutta to a temporary camp 15 miles south of the city along the Hooghly River.

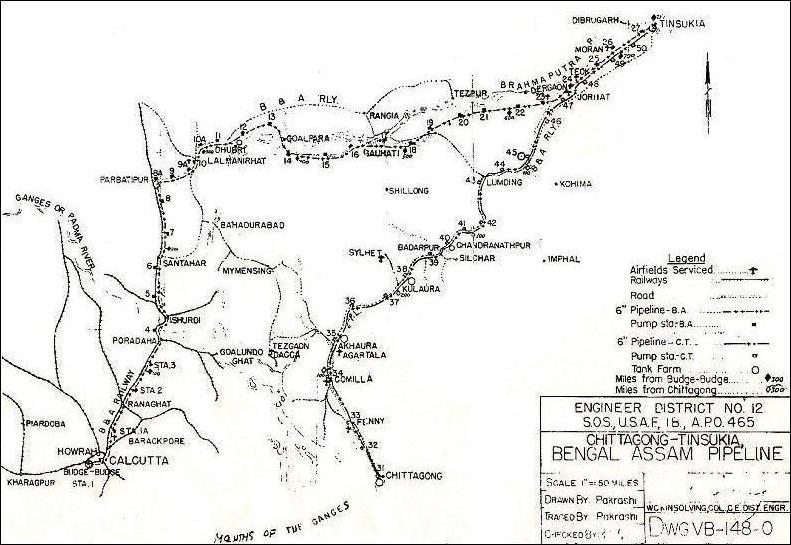

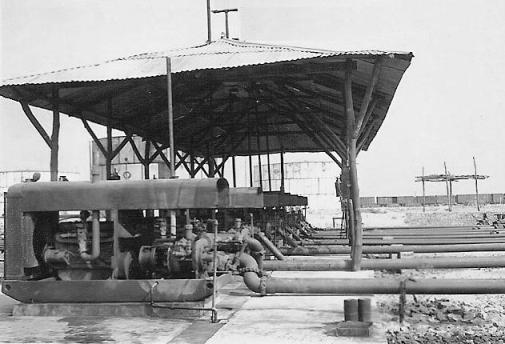

Our permanent company headquarters would be built nearby at a place called Budge-Budge, a huge petroleum pipeline complex, where the tankers loaded with 100-octane aviation fuel would dock to pump the fuel into giant storage tanks. We also operated maintenance and repair shops that serviced all the pumps and equipment at the 13 pump stations and tank farms that we would eventually run. The 6-inch pipeline we operated pumped 100-octane aviation fuel to supply various air bases in the Calcutta area and up into Assam of NortheastIndia. Combat cargo transports plus fighter planes were located in various places in Assam. These airfields were the basis for the Air Transport Command to fly supplies and fuel over the "Hump" (The Himalayas) into China.

We operated and maintained the first 350 miles of this 1,800-mile-long petroleum pipeline that was known as the "Infinity Line." It stretched from Budge-Budge through Assam, Northern Burma and along the Stilwell Road and the older Burma Road to Kunming, China. The U.S. Army also had a pipeline that serviced airbases near Dacca and Chittagong that ran up to Tinsukia and was tied in to the pipeline through storage areas there.

CLICK HERE FOR ENLARGED MAP |

Northwest of Calcutta in 1944 the U.S. Air Force sent the latest Boeing bomber, the B-29Superfortress, to newly constructed air bases in India. A separate 6-inch pipeline from Budge-Budge supplied severalB-29 bases. Those planes flew from the bases in India to bomb Japanese-held areas of China and Southeast Asia. They remained based in India until islands like Saipan and Tinian in the Pacific were captured and airbases were constructed there.

Within a week of our arrival in Budge-Budge, I left with several men and our Staff Sgt.to travel to our assignment, Pump Station #5 near Malanchi. We carried our duffel bags aboard a train that transported us north to the station. The supplies and equipment assigned to us were packed aboard a flatbed G.I. truck which I believe was a 6x6, our old workhorse.

When we arrived, the pipeline construction company had already left the site. Unfortunately, they only partially completed the pump station, living and mess quarters. We kept busy finishing the mess and cook building along with a basha, the term we used for living and sleeping quarters. The pump station building was composed of a good sized corrugated tin roof supported by several wooden poles. The pumps were connectedto a GMC 2½-ton truck motor, all mounted in a metal frame that included a gasoline tank.

The pump stations were located near existing railroad platforms in villages approximately30 miles apart. We drove a truck to the platform every day to meet the train on which the 789 E.P.D. Company had a supply car manned by one of our own men. Supplies of all types and mail were carried on this car and our personnel could travel on it going up and down the line.

In Bengal and also in Assam province, the 6-inch invasion pipeline was buried in the railroad ballast. The railroad bed was built well above ground level since this large area was under water during the monsoon season. Leeches, nasty blood sucking creatures, were thick in the area. Along with the mosquitoes, they made life miserable throughout India. Malaria, a disease transmitted by the Anopheles mosquito, was held at bay by daily swallowing Atabrine, a quinine substitute in World War II. This drug gave our bodies a yellowish cast. We alsoinstituted malaria control measures to keep the immediate pump station areas relatively free of breeding grounds for those critters. I've recently read that more G.I.'s were laid low by illness and unsanitary conditions over in the China-Burma-India Theater (CBI) than were felled by the Japanese.

We had our own cooks at the pump station and being next to the railroad, we got oursupplies delivered daily, if available. We would buy large banana stalks from Indians and hang the stalks to ripen. We picked a banana from the stalks whenever we wanted. The army used a "Lister Bag" for storing and dispensing drinking water. It was a large rubberized fabric bag with several push-type faucets all around the bottom.

We went skinny dipping in the Ganges River a few miles south of our station. It wasnear the railroad, but the tracks were so high above the river that we simply turned our backs to the train if one went by.

One day a local Bengali told our English-speaking Babu (Indian labor foreman) that amarauding animal had attacked one of their village cows and killed it. We jumped at the chance for some excitement and several of us took off with our weapons to hunt it down. I carried a 30 caliber, round nose clip of ammunition for use in a carbine. Fortunately we didn't come across whatever had been killing the livestock. Later we realized that had we found a tiger or leopard, only a high-powered hunting weapon and proper ammunition would have stopped it.I shudder to think what might have happened if we had tried to use our puny guns on such a powerful animal.

Pipeline activity increased daily. The pipeline construction companies whose job wasto install the 20-foot lengths of 6-inch pipe in the ground where it ran along the railroad did not check each pipe for obstructions before coupling them together. Evidently they also forgot to block off the open end of the pipe when they knocked off duty. Our Job was to finish the necessary construction phase so that the guys down at Budge-Budge could start cleaning and flushing out the line with water.

At our first Reunion in September, 1989, many tales were told of the various obstructionsfound in the pipeline. Lumber, debris of all kinds, snakes and dead animals were just some of the items removed fromthe pipeline. Our maintenance section created a device made of metal and used tires to clean the inside of the pipeline. It was dubbed the "rabbit." The methodical cleaning of the pipeline, by pumping water to push the rabbitthrough the pipeline, advanced mile by mile until the day came when 100-octane aviation fuel was introduced into theline.

That was the day of reckoning. Leaks were everywhere! They had to be located and repaired.The location of the leaks and the weather determined the ease of repair. In some cases it was downright dangerous to correct the problem. Because the pipeline was laid in a trench, fumes from the gasoline could make a G.I. pass out while he was knee deep in the stuff. To top it off, he had to be alert to the possibility of fire or explosion.

The men who fixed leaks in railroad switch yards really had a bad deal. Red hot coalsfrom the engine boiler grates were routinely dumped by the fireman onto the rail ballast. Any spark or flame could ignite the gasoline fumes even when quite a distance away from the repair site, causing a fire or explosion if the proper air-to-fuel mixture was present. In addition, many Indians lived in hovels next to the pipeline and sparks from their cooking, etc., presented a hazard with a potential for great loss of life and property. Our equipment for repairing pipeline leaks and fighting resultant fires was very limited. Yankee ingenuity was a necessity to create our own tools, such as the rabbit.

Because the pipeline could develop leaks at any time, every pump station sent a G.I.periodically (every 2 or 3 days) up the line to the next station to check the 30 mile distance for leaks. Eventuallywe hired Indian pipeline walkers for this job. To walk the pipeline, I got up early and started as soon as it got light. I either walked or rode if I could hitch a ride on a coolie-powered hand car. The hand car that rode on the rails was generally propelled by two men lifting and pushing down on a long handlebar (kind of like a teeter-totter). It was called coolie powered because "coolie" was slang for an Indian who did manual labor. Sometimes I'd ride in the cab of a steam engine that was going my way. This was rather risky since I could easily pass by a leak and not spot it.

I'd get to Pump Station #6 before dark, eat some chow and rest before returning to P.S.#5 the next day. One day several hours after I started walking, a motorized handcar carrying a British officer and his Indian soldier stopped. They offered me a ride which I eagerly accepted. When we arrived at their work camp, he invited me to have a cup of tea. The British camp was near a wooden trestle bridge which was being rebuilt by their men.

In the early days of pipeline walking, I had my first encounter with a flock of vultures.I had no idea if those carrion eaters would be a menace to me, so I gave them a wide berth. It was a terrifying experience. In addition, all snakes had to be considered poisonous and there were plenty of them around the raised rail bed during the monsoon season.

I carried halazone tablets for purifying my canteen water which was secured at a village

|

Everything that was not built several feet above ground level in the Province of Bengalwas inundated during the monsoon season. The dirt roads between villages were very primitive and quickly became quagmires when the rains came. During the monsoon, the elevated railroad was used for foot traffic too. It was the main route for getting to each station and to Calcutta.

The time came when I was transferred to Pump Station and Tank Farm 8A at Parhdtipur. This was 235 rail miles north of Calcutta. I was quartered with the other 8A pump station men in the 721 Railway Operating Battalion Camp. We lived in British-type double-roof canvas tents. A separate canvas roof was hung above the tent roof to shade it and allowed air to flow between the two roofs to carry away the heat. The tent was built over a concrete slab with raised curbing on all four sides.

We slept on Indian-made beds of a rough lumber frame laced with jute roping whichreplaced the springs normally found in a bed. Because of humidity, the jute constantly needed to be tightened or it would sag and be uncomfortable to sleep on. To protect the bed frame against termites, each bed leg was immersed in a can of water. For storage, we used metal G.I. or wooden Indian footlockers. Some of us made standing cabinets to hang clothes. I made one using a salvaged wooden box.

We were able to communicate from station to station primarily by the use of army fieldtelephones. Headquarters also had teletype machines with dispatchers operating them. Certain pump stations had these machines and the messages were then relayed to the other stations by telephone. ,

The 8A pump station had no teletype. However, since we were a primary transfer point for transshipment of 55-gallon drums of motor fuel from the broad gauge to the meter gauge railroad which the Railway Operating Battalions (R.O.B.) controlled, we had a more extensive telephone setup than many of the other stations.

Communications between stations was swift. Rarely did any pump station not know when the brass at Headquarters were on their way up by train. The further the station was from Calcutta, the more time the G.I.'s had to get their area shipshape.

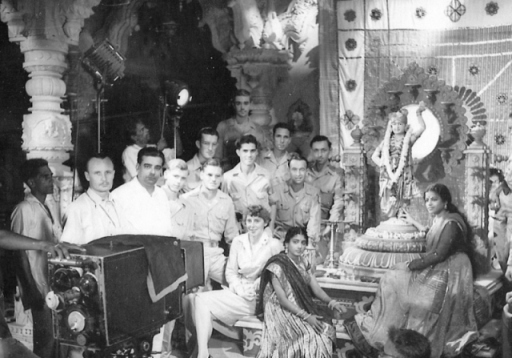

My transfer to Station 8A and being quartered with the 721 R.O.B. was in all respects agood deal. I played the trumpet in a band the railroaders had. This was a most welcome way to relax and kill time when off duty. We played big band music at the showing of 16 MM movies in an outdoor theater at the station. As a result of being in this band, I was placed on

|

The band traveled by train in the spartan type of coaches used on this meter gauge military railroad. Our cars had to be ferried across the wide Brahmaputra River since no bridges were built before or during the war.

At the end of the eleven days, we disbanded at Tinsukia, not far from the border of Burma.Lily Pons and Andre Koslelanetz along with their two principal accompanists flew over the Hump to China to continue the tour.

For a time I was assigned as a courier for our outfit's meter gauge railway supply car.My route was north from Station 8A to the farthest station, P.S. #13, not far from the Brahmaputra River in Assam. My most memorable incident while a courier occurred in that far outpost. At the 8A, we transferred supplies and mail from the broad gauge supply car to the meter gauge supply car which I rode to P.S. #13. It was my responsibility to deliver those supplies and mail. At each station, the supply car stopped by a raised earthen platform with ramps at both ends for loading or unloading supplies. Each day a truck from each pump station met the train to pick up their supplies.

I would board my supply car after the G.I. train crew had prepared the train to run upthe line. This crew drove the train to Lalmanirhat where another R.O.B. crew took over and drove to my last stop. At that point my supply car would be shunted to a siding and the train would continue on. The same evening the supply car would be hooked up to another train heading back down to Parbatipur in the early evening. At P.S. #13, the waiting pump station truck would haul me and whatever I had for them to their living quarters. I always made sure the supply car was locked to prevent theft.

Since the pump station was only a short distance away, when I heard the train's whistleas it entered the railroad station yard to pick up my car, I knew I had to immediately leave the compound and get to the supply car pronto. One day I wasn't paying attention and didn't hear the whistle. The whistle I finally heardwas the one the train blew as it was pulling away with the supply car. I chased the car all night utilizing any means available. Fortunately a jeep fitted with four flanged rims that could ride the rails came by. The railroader G.I.'s took pity on me and gave me a lift as far as they were going. I then hopped a ride on a train headed for Parbatipur. When I caught up with the car, it was already on the siding at Parbatipur. Not long afterward, the guys from 8A came to get me. The car had not been broken into. This was a relief as a courier is responsible for the car'scontents. If anything had been missing, I would have been court marshaled!

Many a village suffered serious fires when the Bengali's tried to use the 100-octaneaviation gasoline as fuel for their lanterns or stoves. Their homes were only mud-lined bamboo walls with a thatched

|

A few months before I came to the 721 R.O.B. Camp, a disastrous wind-driven fire almost totally destroyed the camp. It raced through the buildings and bashas which had thatched roofs and walls of bamboo with a hard surface of clay, lime, cement or stucco. The men who were living there lost everything except what they were wearing. When they rebuilt the camp, the mess hall, shower and latrine, company headquarters and recreation hallwere constructed in the materials mentioned before. However, the living quarters were replaced with the safer British type double-roof army tents that accommodated four men. I lived in one of those for over a year.

I received training in pump station operation and was performing a pump station operator'sjob. In those war days, it was necessary to climb up a steel ladder on the outside of the huge 10,000 barrel gasolinetank and drop a weighted steel tape down to determine the volume of gasoline remaining. A plumb bob was attached to the end of the tape and the tape had a special paste smeared on it. As I unwound the tape in the tank, the paste would wash off. When the plumb bob touched the bottom of the tank, I could determine the depth of the gasoline by where the paste was left on the tape.

One day during the monsoon season, a low but fast-moving squall-line cloud bore down on me as I was performing this operation. Squall-line clouds were quite dangerous as they could easily have blown me off the storage tank. There can be lightning and rain accompanying such as disturbance. All I could do was to lie down flat, grabbing the ladder with both hands. Thank goodness the hatch was near the ladder as it added a little more protection while I hung on.

My best buddy was Charles Irminger who hailed from Kansas City, Missouri. We worked as a pair on rotating 8-hour shifts of the 8A pump station. I believe we rotated shifts weekly. Those pumps went full blast 24 hours a day.

As 1944 turned into 1945, our company employed Indian laborers for various jobs especiallyfor digging and pipeline walking. Charlie and I supervised an English-speaking young Muslim. Shahab Udin, who was the "Babu" of his crew. Supervising the Muslim crews who worked our shift required tact and understanding of their customs, such as not asking a Hindu or Muslim to touch certain types of food or making a remark that might offend their religious beliefs.

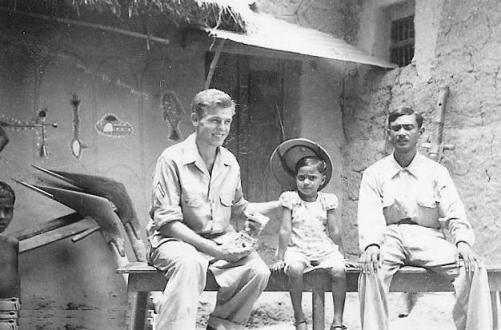

We were invited by Shahab, our young Indian foreman, to visit his village when he returnedwith his monthly paycheck. It was many miles from Parbatipur so we rode the broad gauge train to get there. We left the train at the station nearest his village and set off by foot across elevated pathways bordering rice paddies. The village was built on elevated ground surrounded by coconut and banana trees. The homes were the typical bamboo walls covered with smooth mud and thatched roofs.

Charlie and I had a small supply of hard candy which we presented to Shahab's youngest daughter. We enjoyed seeing his home and eating a meal prepared by his wife. In a room by ourselves, Shahab, Charlieand I sat in the proscribed Moslem custom - squatting down with our knees bent. The women and young girls ate in a separate room. His wife was most gracious and we encountered no rudeness from his neighbors. Though we could notunderstand a word from anyone, pantomime and smiles made that day one I've never forgotten.

This area of India later became part of Pakistan and is now known as Bangladesh. TheMoslems and Hindus fought for separation and many were uprooted and forced to flee to a safe area. It was a bloodbath after India's independence was granted and the British left. I've often wondered if Shahab and his family found safety in those tumultuous years after we left in 1946. The partitioning of India in 1946 and 1947 brought death and destruction to many Moslems and Hindus, especially in the Province of Bengal.

In December of 1944, I spent a rest leave in Madras on India's southeast coast. Theisland of Ceylon lies in the Indian Ocean across from Madras. At this time the crucial "Battle

|

My wartime service in India, since we were never in a combat situation, was not likethose who fought in the European Theater of Operations. Parbatipur was not very far from the British hill towns known as Darjeeling and Kalimpong. If we could get a three day pass, it was worthwhile to hop a train and transfer to what was known as the "toy train" to Ghoom and Darjeeling. The rails that toy train rode on were only 24 inches apart and the cars were about 5 feet wide. The engine's boiler was on a slant when on level ground, but as it rolledup the grade from the plains into the mountains, the boiler became fairly level. Two men would ride in front of the engine and throw sand on the rails for traction.

At Darjeeling we would stay in an English home that offered G.I.'s a bed and meals. Ifthe weather cooperated, we could see the Kachenjunga mountain range which includes Mt. Everest.

In August, 1945, the Japanese signed their unconditional surrender documents aboardthe battleship Missouri. After that, our pipeline operations rapidly wound down. Everyone began counting his points toward discharge and weeded through accumulated items to decide what would be left behind or sent home.

|

I'm not sure which month I actually left Parbatipur for the last time in 1945 and boardeda train on the old broad gauge Bengal and Assam Railroad to head down to the 789 E.P.D. headquarters in Budge-Budge.I spent Christmas and the New Year there. I was surprised to learn that many of the guys had already gone home. In fact the 1382 E.P.D. had taken over the camp. The "ole man" Capt. Peterson, our commanding officer, was gone. 1stSgt. Harry Berman and several Staff Sgts. who had the proper amount of discharge points were headed on the long tripback to "Uncle Sugar." I had to cool my heels for a few more months, awaiting my travel orders to Camp Kancharapara for processing and assignment to a specific troopship back to the good old U.S.A.

I had access to a bicycle which I rode over to the pipeline complex we had operated alongthe Hooghly River to watch the freighters and troopships arriving and departing from the King George Docks in Calcutta. Each troopship was loaded with men and women from the CBI who were going back to the States. I knew with each ship, several thousand personnel with more points than me were now off the list and my time to go back was coming nearer. During that waiting period, I and several other men at Budge-Budge wandered around Calcutta visiting the city from its attic to the cellars. Of course several areas were off limits to military personnel and we didn't visit them.

Fifty years later, images are not as sharp as they once were. I can't begin to describe the sights, sounds and smells that made up Calcutta. While India is rich in history, it is economically poor. The India I knew is different today in many respects. During World War II, Calcutta had a population of three million. I recently read that nine million live there now. One buddy who was in Calcutta during the war expressed his surprise after visiting Bombay recently. He was astounded to see its modern Marine Drive and downtown areas. However when he got into the area bordering the city and the countryside, it was still very like it was back in 1944.

|

Finally the day arrived! Travel orders were cut for me to pack up and travel to Kanchardpara for final processing, etc. I was really on my way. Still, it was "hurry up and wait" which prevailed in India. While I was impatiently waiting there, I met Glen Hille, an Air Force G.I. from Fort Wayne. I knew him because I went to high school with two of his brothers. Ironically, Glen became my next-door neighbor when Joan Augspurger and I set up housekeeping in our first home on Smith Street. We lived there for 19 years and raised twogirls and one boy.

On February 29, 1946, several thousand G.I.'s and I packed our duffel bags and boardeda truck convoy which drove us down to the King George Docks to board the U.S.S. General Hodges. By that time the Indian people of Calcutta were rioting against the British in their quest for independence. Our convoy had to travel through very hazardous areas and the trucks were pelted with stones and other debris thrown by rioting Indians. The trucks were covered by canvas to help protect us from the objects being thrown. Luckily I was not hit. To make matters worse in Bengal, Moslems and Hindus were at each others throats, fighting to become independent states. Mass killings wore becoming a way of life.

After twenty-three months of overseas service in India, I was really starting thelong trip home from half way around the world. Only when the ship sailed and India became smaller and smaller and finally faded out of sight, did I completely believe nothing would require us to abort this long-awaited journey.

The voyage lasted 30 days. It carried us through the Straits of Malacca, on past Singaporeoff the coast of China and up to the Philippines where we refueled and secured provisions. I saw Corrigidor Island as we sailed into the Bay of Manila. There was scuttlebutt that the troopship which left Calcutta just before us was damaged while proceeding into the Bay and was delayed since repairs had to be made before they could sail home.

Leaving the Philippine Islands, we still had a journey of about two weeks left beforearriving on the West Coast of the U.S. Our ship did encounter a bad storm in the Pacific Ocean, however, we got through it safely. The Pacific Ocean swells would have us continually pitching fore and aft and rolling sideways. The long sea voyage concluded on March 29, 1946 as we sailed into the Strait of Juan De Fucca through Puget Sound and docked at Seattle, Washington, our port of disembarkation.

Fort Lawton, an Army post in Seattle was the processing point for shipment to my separation center. It was here I made my telephone call home and my folks heard my voice for the first time in two years. How I enjoyed my ride in a troop train from Seattle through the western states of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Utah and Colorado. The train journey ended at Camp Atterbury, just south of Indianapolis. Finally on April 5, 1946,I received my Honorable Discharge along with mustering out pay, bus travel voucher to Fort Wayne, duffel bag loaded with permissible clothing and belongings plus a lectures on becoming a civilian again. After three years and one month in the Army of the United States, I left the service as a Corporal (Technician Fifth Grade).

It takes much effort and research to write these memoirs without colorfully stretchingthings. I never kept a diary during the war years. I did have a few pictures (with no writing explaining what they were), some maps, souvenirs and printed information. Unfortunately, when I left the service, I was not given a roster listing the men in 789 E.P.D., and their addresses. For 39 years I had no contact with anyone. In 1967 I wrote from memory the lion's share of this material and revised it again in 1983. When I did make contact with a man from my old outfit in 1985, this led me to hunt down others including the old company commander. I was successfulin getting 13 service people and their spouses including Capt. Peterson to our first reunion which I held here in Fort Wayne in September 1989. This reunion came about through the ex-CBI Roundup magazine and my having joined the CBl Veterans Association in 1981. My outfit's reunion provided me with a wealth of information and a fantastic number of pictures, maps and printed material. A big payoff for me was meeting two of the guys who were stationed with me at Pump Station 8A. In conclusion, I owe my sister. Juanita Harsch, ever so much. She wrote most of the letters from home and had larger pictures made from the negatives I sent home. My camera snapped pictures that were two inches square, very small indeed. I'm thankful that I came through the war with no wounds and without having to kill anyone. Best of all was coming home to my family! |

MY LIFE AS A G.I. JOE IN WORLD WAR II

by Thomas Ray Foltz

(1924-2010)

TOP OF PAGE PHOTOGRAPHS PIPELINE MAP

789 EPD UNIT HISTORY THE LONGEST PIPELINE IN THE WORLD 1944 BOMBAY EXPLOSION

E-MAIL YOUR COMMENTS THE CBI THEATER

Copyright © 2007 Thomas R. Foltz Adapted for the Internet by Carl W. Weidenburner