|

A Memoir of

Julius Palmer Edwards

China-Burma-India Theater

of World War II

1943 - 1945

Written by Dr. David T. Fletcher (Julius’s grandson)

in consultation with Bonnie J. Edwards (Julius’s first daughter)

and reconstructed mainly from his oral recollections

and World War II CBI Photo Album

This memoir is also available in PDF format.

Additional photos at World War II CBI Photo Album

Scroll down to continue

Introduction

We don’t know exactly how much Julius knew about the places he would see in the CBI Theater before he left the U.S.A. in early 1944. But one wonders how well-known to a non-college educated youth from rural Rhode Island would be such books as Lin Yutang’s My Country and My People, Pearl S. Buck’s The Good Earth, Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu series, Earl Derr Biggers’s Charlie Chan books (or the numerous films with these two pop characters), H. George Franks’s Queer India, or educational works about the Far East – such as Joseph Rock’s many articles in National Geographic and the book designed for school-children, titled Asia, The Great Continent (published in both 1931 and 1937). I suspect that he did not know any of these works well (if at all) – or, if he had seen some written, pictorial, or film depictions of Asians (as entertainment or in the national media), [1] that such images were probably not deeply impressed on his mind. Almost certainly, Julius would not have personally known any Asian people (Indian, Chinese, Japanese, or other) prior to his military service overseas. Of course, he also would not have known (probably until he received orders in early 1944) that he would be sent to serve in the CBI Theater. But in any case, Julius did not mention having any preconceptions about Asia before 1944. His experiences while in India, China, and the Mariana Islands would leave a deep impression, however, which was subsequently reinforced by numerous post-War reminiscences with one of his friends, fellow CBI veteran Charles H. (“Charlie”) Chase of Derry, NH. [2]Later in his life, Julius read several books and articles about the CBI Theater and the Hump pilots, was active in the American Legion in Hope Valley, RI, and even considered returning specifically to China to visit the area in which he had served from mid 1944 - early 1945 (within Sichuan Province, mainly between Chengdu and Leshan). Unfortunately, he was never able to take that trip. My decision in 1997 to marry a lady from Taiwan, born of two Nationalist refugee parents originally from China, no doubt caused Julius to recall some old memories that he had not mentioned in any detail to other members of our family for roughly forty years. He asked me at one time, before I ever knew that I would visit the Chinese Mainland, to see if I could find any information for him about Pengshan (near Chengdu) or a Chinese officer he had known there. I agreed, but was unable to provide very much to satisfy his curiosity. Julius passed away in 2007, but my search to answer his request has continued.

I saw Julius’s WW2 CBI photo album maybe once as a young boy, and only briefly; much later, he casually showed me some of his pictures again, when I was in Graduate School. Other family members remember seeing the album just as rarely while Julius was alive. I only carefully studied his extensive collection of wartime photos taken in Asia and the Pacific after Julius died, when I inherited his War Album. How I wish now that I had spent more time going through it with him while we were together. He was a lifelong collector of antiques and kept some mementos from his service years along with hundreds of other, unrelated items that he acquired over his 84 years. I now have his military items, and will include pictures and brief descriptions of these in this memoir, to complement his photos.

Much of what he saw and experienced regrettably has been lost to us, and we can no longer ask Julius our many questions. To add to my personal knowledge of his time overseas, since Julius’s death I have visited China four times (for three weeks each tour), once enjoying a memorable visit to a small village just outside of Julius’s old air base at Pengshan (A-7) in Sichuan Province. [3] I have also visited several historical sites in Taiwan, read a fair amount of 20th century Chinese and World War Two history, and have recently begun to study the history of the 468th Bombardment Group (in the 58th Bomb Wing, XXth AF), as well as the larger mission of the U.S. soldiers and airmen in the CBI and Pacific Theaters. These studies are ongoing. I learn more and find additional source materials each time I explore.

The following memoir of Julius’s experiences during the War was written with the aid of Julius’s first daughter Bonnie (my mother), who remembers – from the time she was a child – hearing some of his stories and also visiting a few of Julius’s war-time friends. For the benefit of future family members, interested readers, and CBI/WW2/Asian-Pacific history researchers, we have attempted to present here as many of Julius’s oral recollections as we could, as closely as we could recall them. Apart from many private letters sent home to his wife Adelka in 1943-1945 (which have not survived), Julius could not be convinced to write any of his war-time memories himself. He also never attended reunions of CBI veterans, though he knew about such events in the 1990s and early 2000s; this was because he regarded these reunions as mainly being composed of CBI airmen and not the ground crew people he had known. These stories are all his own and were related orally at different times either to Bonnie or to myself. I have supplemented them only sparsely with information gleaned from other sources that describe his military unit(s) and the locations he visited, in the interest of filling some gaps or solving mysteries concerning what he specifically said to us. Where I added anything beyond his personal stories, I have footnoted the sources that were used so that readers may refer to them.

Though this record can never be as complete and detailed as we would like, we sincerely hope that anyone interested in this period and the people who lived in it will enjoy and find useful the photo collection that Julius assembled, and the explanatory notes that we have placed alongside it at the New England Air Museum (NEAM). [4] With these materials we speak for Julius, to the limited extent that we are able.

I also hope that this may inspire others to make similar collections and memoirs available; and that if anyone viewing these materials recognizes or knows more about the people or places discussed, they will contact me (or NEAM) to contribute to this record. I will also continue my research and additions.

Dr. David T. Fletcher (Gibsonville, NC), Aug. 2015 – Oct. 2016

1 Julius may have read some of Kipling’s poems and stories about India, and might have seen the 1939 film Gunga Din

(but before 1943?).

For a discussion on the gradually shifting image of China promoted in popular U.S. media circles in the 1930s,

see: Pattison, Erin, "Changing Perceptions of China in 1930s America" (2012).

All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). Paper 769.

http://openscholarship.wustl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1768&context=etd.

Media newsreels of events involving Japan (and India) would have been common in the early 1940s, before Julius’s enlistment.

He must have been aware of some general news concerning the war against Japan, and he would have known that the British then controlled India.

Madame Chiang Kai-Shek (Soong Mei-ling) also addressed the U.S. Congress concerning aid for China in Feb. 1943, just after Julius enlisted in the

U.S. Army; and Hilda Yen and other Chinese female celebrities had been making efforts to obtain U.S. aid for China (see Patti Gully, Sisters of Heaven.

China's Barnstorming Aviatrixes: Modernity, Feminism, and Popular Imagination in Asia and the West (Long River Press, 2007), on three Chinese women

aviators who promoted China’s cause in the U.S.A. in the 1930s; also Hilda Yen in Washington D. C. in April 1939 at:

http://www.shorpy.com/node/6799).

But how much Julius knew about these people or cared about events in China or India before his arrival in the Eastern theatre in 1944 is unknown.

2 Julius seems to have first met Charles H. Chase in Pengshan, China in 1944 (as will be related in this memoir). “Charlie” became a long-time friend of Julius and his family. He is featured in many of the photos in Julius’s War Album, and though his own photo album of WW2 pictures seems to have been lost (so far as I am aware, following inquiries to his family), his name has been inscribed on a monument honoring the WW2 veterans from Derry, NH. See: “Derry, NH’s WWII Honor Roll.” Nutfield Geneology (blog). Tuesday, November 13, 2012. Accessed August 21, 2015.

http://nutfieldgenealogy.blogspot.com/2012/11/derry-nhs-world-war-ii-honor-roll.html.

3 The story of David Fletcher’s meeting with a former KMT soldier at Pengshan will be told later in the memoir.

4 The scanned collection of Julius Palmer Edwards’ War Album was deposited in the NEAM archive in 2015, along with a Captions document created by David Fletcher and some other short explanatory documents. The Captions document is undergoing some revisions, and will be resubmitted along with this memoir upon its completion.

Julius Palmer Edwards [by late 1943] was with the XXth Army Air Corps (Bomber Command), 58th Bomb Wing, 468th Bombardment Group, 794th Bombardment Squadron (ground crew; trained for airplane and automotive mechanic work), and was probably in the 15th Bombardment Maintenance Squadron from Nov. 20, 1943, until it merged with the 794th (the 15th merged with the 794th in October 1944). [5]

As far as we presently know, these are his service details. (Though some service records have been found, most WWII U.S. Army personnel records with dates and locations were lost in a catastrophic fire within the U.S. military records archive building in St. Louis in 1973.)

1943 [Julius was aged 19 in Jan.; he was 20 yrs. old as of Feb. 1943]

Jan.15: Enlisted in Westerly [his record says Providence], Rhode Island (his hometown was Canonchet, near Hope Valley); he would soon become a U.S. Army Private.

Late Spring - Early Summer: Basic training in Biloxi, Mississippi (on May 20, he married Adelka Dobrowski in the Jefferson Davis Church in Biloxi). [Note: The information here is correct – I had the date of his marriage and the American spelling of Adelka’s last name wrong in the PPT deposited at NEAM in 2014.]

Summer to September: Trained at Willow Run, MI (Ford Motor Co. Airplane School – graduated in Sept.) [now ranked Corporal]

Winter: Salina, KS (Smoky Hill Army Air Field) [Dates of his time there are uncertain – but probably from late Sept. or Nov. 1943 to Feb. 2 (departure from KS) / Feb. 22 (departure from Newport News, VA), 1944; he described it as very cold then in Kansas; B-29s were being prepared for deployment to India.]

1944 [aged 20-21] (the dates and details of his deployments are educated guesses during this year)

February - May: Feb.: Shipped overseas in Feb. (probably from Newport News, VA) to India, via North Africa; Mar.: transferred in Oran, French Algeria to the troop ship SS Volendam and then sailed through the Suez Canal to Bombay, disembarking at the end of April. [See the memoir for more on the precise route and the dates.] May: arrived in Kharagpur (Camp Salua, B-1) from Bombay (probably via Calcutta).

Summer [precise date uncertain]: Sent to Pengshan, China (A-7) over “the Hump” – i.e., the Himalayas.

By Sept.: Julius was stationed in Pengshan air base (A-7), where he probably stayed until Jan. 1945; in China, he was a motor pool mechanic (working on trucks mainly) and also a driver / assistant undertaker with Chaplain Captain Jesse Leroy (“Lee”) Coburn. Julius was seriouly ill for about 3 months at the end of this period with pneumonia (he may have been in an infirmary in Kunming at that time – uncertain).

1945 [aged 21-22]

Late January [exact time uncertain]: Transferred from Pengshan, China back to Kharagpur, India.

Feb. - early May: At Kharagpur; in early May, he was shipped from Calcutta to Tinian (in the Pacific) via Perth, Australia (on the U.S.S. General Leroy Eltinge).

June 6/7 - August: Stationed on Tinian Island (the 794th was based at West Field); there, Julius said that he saw some of the scientists who were working on the Atomic Bomb when one of these was brought to Tinian. He also was possibly on Saipan briefly during this time.

When the war ended (late August – early Sept.): Julius was flown back to the United States (via Hawaii) – he mentioned flying aboard the B-29 “Lady Be Good”. Transferred from Hawaii through Bakersfield, CA (maybe), and eventually discharged at Ft. Devens, MA in September 1945 (he was there for debriefing for one week). He lived in Rhode Island and Connecticut (near where he was born) for the rest of his life.

A useful reference: A very detailed history of Operation Matterhorn and the 58th Bomb Wing is

In January 1943, Julius went to Westerly, Rhode Island with his mother and signed up for service in the U.S. Army.

He was then about one month short of his 20th birthday. [6] Julius would be assigned to the U.S.

Army Air Corps by the middle of that year, but likely did not know until the Spring of 1944 where he would be deployed for duty. To begin his story and to better understand why Julius later recounted his military experiences during the War in the way that he did, an attempt is made here to investigate his situation in Rhode Island before he enlisted on January 15, 1943.

According to the recollections of both Julius and his family members, he was an adventurous boy. Julius was born and raised in Canonchet, Rhode Island (in the area of Hopkinton and Hope Valley), which then was fairly rural. His parents were land and business owners (his mother also had once been a school teacher), and were relatively prosperous in the town, despite the Depression. They ran an automobile dealership, Edwards Auto Sales, and offered repair services also. Working in the garage and ambitious, Julius learned auto mechanics, sales, and driving early in life (as he said, he was already learning how to drive at the age of 6 or 7). Concerning Julius’s youth, his daughter Bonnie said, “He had a lot of freedom and independence in high school – much more than today’s boys would find normal” (2015). Though his mother had hopes that Julius would eventually enter medical school, he disliked high school and was often rebellious. In fact, he seems to have left home occasionally for extended periods. On one of these trips he said that he went to the 1939 World’s Fair in New York with one or more local friends (when he was 15); another time, at age 16 both he and a friend left home for six-seven months to travel as far away as Tennessee, where they worked for a family who took the two boys in, after meeting them in a church service one Sunday morning. Julius never explained his reasons for these trips to his daughters. Julius was also a daredevil while driving, and once injured his cousin Everett badly enough to send him to the hospital after crashing into a wooden guardrail on the highway while test driving a car at 80 mph.

One pleasant memory of his school years was that at age 12, Julius met the girl who would eventually become his wife. They were of different religious backgrounds and cultures (Adelka was Catholic Polish, and Julius of British heritage), but maintained a long-term childhood friendship. They went to different middle schools, but both attended Westerly High School; Julius was one grade ahead of Adelka there. Bonnie remembers that they each disliked high school, and so both Julius and Adelka dropped out, probably around their Junior years. Adelka eventually went to work in a war supplies factory in Westerly (possibly in 1942; we have a photograph of her working there in early 1943), and Julius continued working in the family’s auto dealership (the Edwards “garage” still exists in Hope Valley as of 2016).

Long after returning from the War, Julius would tell his two daughters (Bonnie and Sherrie) that he had dropped out of high school in order to enlist, that he was “under-age” when he did so, that his mother had to accompany him to co-sign when he joined the Army (we always presumed that he volunteered), and that he then traveled around the world and returned home by age 21. However, his Enlistment Record – which we discovered many years after Julius’s passing – reveals a somewhat different story. What follows (up to January 15, 1943) are concluions based upon our recent examination of evidence concerning Julius’s enlistment. The results below are not what he told us about his entry into the War.

Immediately after Dec. 7, 1941 (the bombing of Pearl Harbor), joining the military became popular in RI. According to Bonnie, Julius said that several of his friends had already signed up for military service by later 1942. However, he (and at least a two others in his circle of close friends – including Julius’s cousin, Everett Palmer, and a friend named James E. Dow) held off for roughly a full year after the War started. [7] The minimum age for the draft at the beginning of 1942 was 20 years of age, and all 20 year-old males were required to register with the Selective Service. But in June 1942, the registration age was lowered to 18. (Julius would have had to register that summer for the Draft.) Then, after news announcements in later 1942, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9279 on Dec. 5, 1942; this lowered the induction age to 18, and also prevented all further voluntary enlistment for men between the ages of 18-37 in any branch of the U.S. military, effective immediately. From that point until the end of the War, all enlistees were to be officially drafted by lottery and assigned to Service branches as needed by the government.[8]

Julius was 19 after Feb. 1942, and had probably been out of high school by then for about two years. Though his parents owned farmland, Julius was not a farmer himself; and the auto business became slow after the War began, largely due to the government’s need for fuel. Bonnie said that his parents probably did not want Julius to enter the military in 1942; but he seems to have rarely undertaken any course of action (at any time during his life) based upon his parents’ wishes. Whether he was hoping – perhaps like many of his friends – to stay out of the War for as long as possible is unknown. But what is clear is that Julius did not volunteer for the Service before the deadline of Dec. 5, 1942. He very likely knew that he would soon be drafted. Also, Julius did not drop out of high school in order to join the Army, as he later maintained (and he returned home at age 22, rather than age 21).

Why then did he tell his alternative story to his daughters? Bonnie supposes that Julius’s enlistment story was fabricated because he wanted Sherrie and herself to be well educated. Thus, he covered his real motives for leaving high school with an explanation of his desire to join the war-effort. I would add

that he was very proud of his service in the War after he returned, and that his version of the story also allowed Julius to adopt a more admirable fatherly role model, compared to his actual, frequently unruly behavior as a youth before the War.

Despite his initial hesitation to go to war (which, given the circumstances, was very understandable; his two older brothers, Emory and Phillip, also avoided the military and worked in factories during WW2), once he received the unavoidable call, Julius appears to have embraced his duty without complaint. One consideration which may have encouraged him was that Adelka’s father had volunteered for military service during World War One. Walter Dobrowski – a first generation immigrant from Poland – had signed up in Canada before the U.S.A. became officially involved. His wish had been to help the Poles, as he still had family living in Poland – and this concern remained on his mind in 1939 and throughout the Second World War.

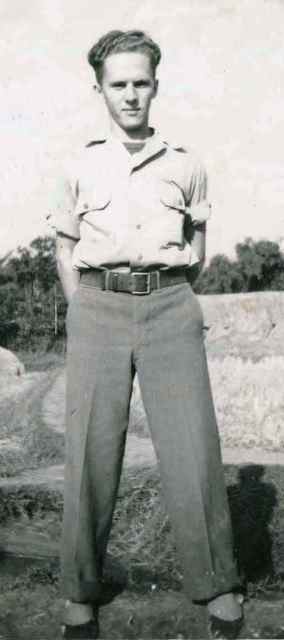

Beyond his somewhat misleading story about his enlistment, Julius’s expression in photos taken of him on the day that he went to Westerly to sign up are also interesting. His demeanor suggests a James Cagney-like, tough-guy’s composure – mixed confidence and bravado are evident. He also sported that look in a photo taken in Michigan (see the photo below). But photos taken of him later in India, China, and on Tinian occasionally reveal a different face – there, he sometimes wore a smile.

ADDITIONAL NOTES IN THE TEXT BELOW CAN BE FOUND AT THE END OF THIS PAGE OR BY CLICKING THE NUMBER. USE "BACK" OR THE BACKSPACE KEY TO RETURN TO PREVIOUS LOCATION.

CLICK ON ANY IMAGE TO VIEW FULL WINDOW UNRETOUCHED VERSION.

Julius Palmer Edwards’s Service Details (summary)

[Last Updated in September 2016 by Dr. David T. Fletcher]

The Army Air Forces in World War Two, Vol. 5 The Pacific: Matterhorn to Nagasaki June 1944 – August 1945. Eds. Wesley Frank Craven and James Lea Cate, New Imprint by Washington DC: Office of Air Force History, 1983 (originally published by Chicago: University of Chicago Press/London: Cambridge University Press, 1953). Accessed August 30, 2016,

https://ia600300.us.archive.org/8/items/Vol5ThePacificMatterhornToNagasaki/Vol5ThePacificMatterhornToNagasaki.pdf. [This source will appear in the notes of this memoir as: AAFWW2 V.5, pages.]

The Memoir: Julius Palmer Edwards's Stories about World War 2

Julius’s life before his enlistment (in Jan. 1943)

Air Base A-7, c. Sept. 1944

|

In the Army now (1943)

Julius did his basic training in Biloxi, Mississippi in early 1943.[9] Regarding his hand-to-hand combat training, Julius said that though he was the smallest man in his company, he was often paired with a much larger man during their practice. In his later years, he recalled the rough treatment he received at that time with a meaningful smile. Presumably near the end of his boot-camp training, Julius married Adelka Dobrowski (“Decki”), his childhood sweetheart, who traveled to Mississippi at his request to be wed in the Jefferson Davis Church in Biloxi.[10] The wedding took place on May 20, 1943. Several pictures in the War Album commemorate the event, and feature another soldier and his recent bride who stood up with Julius and Adelka at their ceremony. This pair were Kaye (Fortin or Forten ?) and maybe Larry or Mike Fortin – we do not recall their names exactly. Julius and Adelka met them in Biloxi, and Kaye allowed Adelka to borrow her own wedding dress for this ceremony. Kaye’s husband was later killed while serving overseas. Adelka continued to write to Kaye for many years after the War.

|

|

After their wedding, the newly-weds spent some time together. From that point until later September 1943, Adelka stayed with Julius when he was assigned to the Ford Motor Company Airplane School in Willow Run, Michigan for airplane maintenance and engine repair training. Julius graduated from this program and received his diploma (for B-24 Liberator Heavy Bomber repair) on September 17, 1943.

|

Julius was by then a corporal, and during this summer (probably around mid July), their first child was conceived. (Bonnie would be born, as will be related below, on April 14, 1944 – almost two months after Julius shipped out to India.) At the end of their time in Willow Run, Julius was assigned to the new B-29 air base at Salina, Kansas. Adelka went home at that point to live with Julius’s parents in southern Rhode Island for the duration of the War. The family (Julius’s father and mother, and Adelka’s mother) made the long trip to Michigan to collect her in September and to see Julius off. This was the last time they would meet him before his deployment overseas. Julius was now 20½ years old.

|

In Kansas at Smoky Hill Army Air Field (SHAAF), Julius spent the winter – which he remembered as bitterly cold – probably helping to prepare many new B-29 Heavy Bombers for their transport to India. His training in airplane mechanics would have been for the B-24 Liberator Heavy Bomber – this was the course that he would have had at Biloxi, and his Willow Run diploma specifies the B-24 Liberator. But the B-29s that were being readied in Salina were brand new to everyone then.

We know very little about this period of his service, and there are no identified pictures of the Salina base in Julius’s War album. He almost certainly was assigned to the 15th Bombardment Maintenance Squadron, until it merged with the 794th Bombardment Squadron – his eventual unit while in China, India, and later on Tinian.[11] Apart from his mention of the cold winter, he only told us that he kept in contact with Adelka by telephone while waiting for his orders to ship overseas; and when the time finally came, due to Army security orders he was unable to tell her that he was immediately due to be deployed. They would not be able to speak again for who knew how long – assuming he survived the U-boats and other possible hazards of the crossing to India. The memory of having to say he would call her the next night – knowing that he would not – caused Julius to cry when he recalled it sixty years later.

We’re not in Kansas anymore: Over the Atlantic to North Africa and then to India (early 1944)

Though Julius had traveled rather adventurously within the States as a teenager, this would be a grand journey to parts of the world that no one in his family had ever seen. In fact, he would circle the world. To start, from early February to mid May 1944, Julius was deployed along with the other members of the 794th Bombardment Squadron (in the 468th Bombardment Group) from Salina, Kansas to Camp Salua (B-1), which was located just to the south of Kharagpur, a city 75 miles west of Calcutta in eastern India (at that time, Kharagpur was connected to “Kolkata” by both railway and a very long, bumpy road).[12]

Julius later recounted his itinerary with certainty, but only partially, and without the exact dates of his travel (which had to be worked out – along with details of the ships involved and the locations visited – through extensive secondary research requiring reference to several sources; these are noted below). He said that he sailed across the Atlantic to Casablanca in Morocco, then to Algeria, and then across the southern Mediterranean by ship, through the Suez Canal, and thence to India – first to Bombay, then to

Calcutta (all troops travelling this route went from Bombay to Calcutta by railway). Julius also specifically mentioned traveling on the troop ship SS Volendam, and that the troops were given warnings about the danger of German U-boats, which induced them to maintain silence about their travel arrangements.[13]

|

If the reader will indulge, the following is a more precise account of what was most likely this itinerary. To begin, not all of the soldiers in the 794th Bombardment Squadron traveled by the same route or at exactly the same time. The B-29s were separately flown by their crews to India in stages, across several different flight paths. The ground troops also were divided. Some were deployed westward, across the Pacific to Calcutta and then Kharagpur (and Camp Salua). Others traveled eastward, as Julius did.[14] Julius’s North Africa route is described in the accounts of Dr. Yates Smith (collected at NEAM), and is further illuminated by accounts of the SS Volendam (a Dutch ship) by other writers. A tangential point of historical interest is that the catastrophic, but now little known, “Bombay Explosion” (aka. the “Bombay Docks Explosion”) occurred on April 14, 1944 (Bonnie’s birthdate), at the Victoria Dock in the harbor of Bombay. This was only two weeks before the SS Volendam delivered Julius and many fellow U.S. troops to that city. Julius did not mention this event in his talks with family members now living, though he likely saw the aftermath – a significant portion of Bombay near the harbor-side burned, and many were killed. The reader is invited to investigate this news event (reported somewhat later in 1944) as a “near-miss” historical coincidence. (The “Bombay Explosion” story can be found easily on the Internet.) In his discussion of the deployment of the 15th Bombardment Maintenance Squadron (part of the 794th Bombardment Squadron), Dr. Yates Smith wrote:

| …on the 2nd of February (under secret orders) the Squadron left Smoky Hill Army Air Field, Salina, Kansas, for overseas service. Going to Camp Patrick Henry, Newport, Virginia, the unit embarked 2-22-44, crossing the Atlantic Ocean on the William B. Giles, in convoy, and landing at Casa Blanca; by train to Oran, French Algeria, North Africa on 3-11-44. The unit remained in C.P. 2 area until 4-6-44 on which date it embarked aboard the Oran of Amsterdam, operated by Dutch command and Crew, and going in convoy, led through the Mediterranean Sea, Suez Canal, and thence across the Arabian Sea to Bombay, India, debarking Bombay 4-27-44 and on that date taking a train across India, arriving at Kharagpur, India 5-22-44. Unit then quartered with the 468th Bombardment Group nearby.[15] |

Dr. Smith provides the fullest account of all the individual deployments of the 794th Squadron members from Salina to India that we have found thus far. Among the many routes that he described, only this one (of the 15th B.M.Sq.) fits Julius’s stated itinerary. It also fits with Julius’s statement that he sailed on the Dutch ship SS Volendam. After disembarking from their original troop ships (which took them across the Atlantic) and waiting for about 26 days in Oran, French Algeria, the troops re-embarked for the rest of the voyage to Bombay. One of the ships that made up the second convoy was the SS Volendam.[16] This particular voyage of the SS Volendam and the deployment date are confirmed by Capt. Cornelius “Kees” Haagmans, who sailed on the ship for several years and later wrote his own memoir. He says:

| …[In March 1944] arrived in Naples on the 28th, left the same evening for Mers el Kebir (Oran) where we disembarked those troops. We then embarked 3,035 American forces and sailed with nineteen ships on April 6th to Port Said, the Suez Canal to Aden and with six ships to Bombay where we arrived on April 25th. Here we were lucky again because eleven days earlier on April the 14th there had been a big explosion in Bombay that had killed thousands of people, damaged ships etc. Here we disembarked the troops again…[17] |

“The SS Volendam as troopship during the second world war” (picture from the website cited above)

“The SS Volendam as troopship during the second world war” (picture from the website cited above)

|

And so, Julius arrived with numerous other soldiers of the 794th Bombardment Squadron in Bombay, India. He soon took the train with them to Calcutta, and then eventually to Kharagpur and Camp Salua around mid May. A fair amount of description of the conditions and troop accommodations in India can be found in the memoirs of other soldiers who served in the 468th Bombardment Group during 1944-1945.[18] But I will leave the reader to discover these and now return to Julius’s specific memories.

At some time soon after arriving in India, Julius said that he took a day trip to Calcutta by train (probably a short furlough), and that he traveled on that occasion by himself. While walking through the city, an Indian man called him by name (“Hey, Edwards!”). Julius claimed that he was not wearing any outwardly identifying nametags (though he was in uniform), and that he had never seen the man before. But this Indian man told him that his wife had birthed a child. When Julius returned to his base, he received word from the Red Cross that Adelka had indeed given birth. (The Red Cross did not tell him then whether the child was a boy or a girl; that piece of the news required another month. Julius was infuriated and never forgave the Red Cross for the delay!) In his later years, this Indian man in Calcutta haunted Julius’s recollections. How had the man known him, and about his new baby? That odd meeting became for him a personal brush with the mysteries of exotic India.[19]

India seems to have struck Julius as it did many other U.S. soldiers there in 1944-1945 – as very different from home and in some ways curious, but also very dirty and in many ways unpleasant. He always said that he enjoyed the time he spent in Pengshan (and Sichuan Province in China generally) far more than India. He disliked the beggars in the cities and the filth; and the Indians failed to win his respect. It was not their abundant poverty that Julius considered the problem. He thought many Indians were lazy and unmotivated – thus, he compared them negatively to the industrious Chinese peasants in Sichuan, who were also very poor but comported themselves in a far more dignified and respectable way, in his view. Julius knew that both the British in India and the Nationalist elites in China were harsh masters of the lower classes in each country; but he seemed much more sympathetic to the Chinese than the Indians. Whether he was aware of the terrible famine that had afflicted the region surrounding Calcutta in 1943 is unknown. Chaplain Coburn, whom Julius knew in China (see below), did mention it in a letter in 1944.

Both Camp Salua and Calcutta are featured in many of the photos within Julius’s War Album. He was stationed at Camp Salua twice – first from mid May until his move to Pengshan in 1944 (see below) and then for probably three months from late January to late April 1945 (see my Captions document for his War Album photograph identifications). Julius did not specifically name his military base camp in India for u, nor the dates during which he was stationed there (these were identified through research on his 794th Bombardment Squadron). When he spoke of India, he only told us about “Calcutta” or “Bombay.”

Memories to last a lifetime, made in China

Unlike India, Julius told many more stories about his experiences at the 794th B.Sq.’s forward air base in Sichuan Province, China – base A-7 near Pengshan. Here and in the surrounding country, several things happened to him over a period of roughly half a year that left strong and sometimes deeply emotional memories. These recollections caused Julius to grow excited, frightened, curious, and even sad enough to weep after the War had been over for roughly sixty years. Many of Julius’s photographs are from this period. He also appears in some of the photos and one letter included in the collection of Chaplain Capt. Jesse Leroy “Lee” Coburn (electronic copies of the Coburn collection are also in the Archive at NEAM).[20]

The chronological ordering of these stories may be somewhat mixed; Julius was often not specific about dates or locations. One example of this is his story about his uniform. At some point while he was in the Service, Julius was suffering from rashes and often felt poorly; the company doctor could not identify his malady. Eventually, he discovered the cause – he was allergic to the wool in his issued uniform. Once he removed the woolen garments, the problem disappeared. But when was this? A woolen uniform would not have been much of an issue for him in India, where the spring and summer temperatures of 1944-45 were sometimes 100 degrees F or even more (cotton uniforms were the U.S. Army norm there). But in Kansas (winter of 1943-44) or at Pengshan, located in the elevated southwestern region of China (Fall and Winter of 1944) it could be very cold, especially at night. The soldiers also slept in tents in western China, and often worked outdoors. This may have been when he discovered the cause of his skin rashes and thus changed his uniform material. But possibly as a result of this, in the later months of his China assignment Julius contracted a serious case of pneumonia that nearly killed him and kept him from writing home for roughly three months. His family knew nothing of him then and were forced to battle the fear that he had possibly died.[21] We still possess two quilts which were made by Adelka and Julius’s mother, while they were anxiously awaiting news in Rhode Island during that time. But again – the exact dates of his long illness also are unknown to us, save that it was at the end of his deployment in China.

The end of that period of illness is when Julius was shipped back to Camp Salua (his second assignment there, before deploying to Tinian). We have found that his unit returned from Pengshan by the end of January 1945. Julius claimed that he was shipped out of China by a “southern” route (possibly through Kunming); and that he was in hospital during the time leading up to his shipment back to India. We do not know exactly where that hospital was located (several U.S. military hospitals existed in China – two larger ones were at Chengdu and Kunming, and a smaller one may have existed nearer to Pengshan). We also are not exactly sure when he left China, but it was probably very late in 1944 or January 1945.

Similarly, we do not know exactly when Julius was flown over the Hump from Kharagpur to Pengshan – but here we can make an educated guess. The Pengshan base was completed by the small group of U.S. military engineers sent to oversee its construction in early May 1944 (the base runway was built by local laborers,[22] who provided a colossal and ongoing effort to keep the runway open for business from May until after January 1945; the base was later used by the Chinese military, and it still exists as an active Chinese military air base today). Julius’s first dated pictures from Pengshan are labeled September 1944. But it is possible that he arrived earlier, during the summer, and simply did not have access to a camera before September. Julius did not mention the drenching Monsoon season in eastern India, which began in Kharagpur sometime in June 1944 and extended to September; but he also did not mention his Hump flight to us. He must have taken a flight to get to China, however – the military road from Burma was not yet completed by September (Burma was a famous combat zone then); and he does have some fuzzy pictures of mountains in his War Album, which may be from that flight (or the return). So we estimate that sometime in mid 1944, he was flown over the Himalayas to the 794th’s forward base at Pengshan (designated A-7 by the U.S. military), probably with a cargo of supplies for the remote new base.

Why Pengshan? For the U.S. military, this base was one of four that were specially built near Chengdu by the U.S. Army Air Corps, to serve as staging areas for B-29 Heavy Bomber missions against Japanese targets in Occupied China and in SE Asia. The 468th B.Grp. (Julius’s group) in Kharagpur was assigned A-7 as their primary China air strip. The locations of these advanced bases were supposed to be top secret while they were in use, and they were rarely specifically discussed in military media printed in (or about) the CBI Theater in 1944-1945. This was for two reasons. Not only were the B-29 air strikes considered vital to the War effort and to the morale of the Chinese in this badly mauled country, but the bases themselves were also only lightly defended and could be easily damaged by Japanese air attacks, which might potentially destroy the airstrips themselves and the painstakingly-collected stockpiles of fuel and bombs used by the U.S. bombers – thus rendering the forward bases useless for their purpose. No other U.S. heavy bomber planes were able to reach Japanese occupied areas in the Far East at the time (these CBI B-29s would be the first U.S. planes to successfully attack home island Japanese installations after the one-off Doolittle Raid of April 1942, which had been launched from the U.S.S. Hornet in the Pacific Ocean).

For Julius, there were likely other reasons to accept this duty (notably, many in his unit never went to China; they remained at Camp Salua to facilitate the B-29 missions in that safer, rear base). He did not tell us his feelings upon initially being assigned there, but we might imagine how he felt soon after he arrived, based upon his circumstances and his personality. Serving at this A-7 base was considerably more hazardous than India, for several reasons. A major Japanese offensive pushed deep into southern and western China in 1944 (the Japanese wished to destroy all of the U.S. airbases that they soon learned were located there; their offensive – by both land and air – continued almost the entire time that Julius was stationed at A-7). Chinese “bandits” and occasionally independent-minded local warlords could make travel somewhat unpredictable in this region (Julius mentioned both the Japanese and bandits to us). There was also the long and very dangerous “Hump” flight that was required to get to Pengshan from Kharagpur (this air route killed many men and claimed a large number of aircraft in this period), the relative remoteness of A-7 both in China and from the rest of his unit in India (located on the other side of the Himalayas), a continuous shortage of many basic supplies (all of which had to be flown over the Hump), extreme cold during the winter season, and the fact that the base was a storage depot for aircraft fuel and bombs. Yet, despite these drawbacks (and maybe partly because of some of them), Julius may well have relished the expectation of adventure in this China assignment.

We do not know whether this assignment entailed slightly higher pay. But we can imagine that, aside from escaping India’s great heat and uncomfortable summer Monsoon, Julius might have guessed that he would enjoy a somewhat greater degree of freedom from military discipline and possibly earn higher prestige by serving in China. As things turned out, he would have the opportunity to travel and explore the surrounding countryside as part of the duties he would acquire there. Though trained in airplane mechanics, Julius served at Pengshan in the camp’s motor pool, where he utilized his knowledge of auto mechanics to keep the military trucks in repair. As he said, this position made him rather popular, as he became one of the “go-to” men to sign out trucks from the base, when soldiers wished to go on brief excursions to the local walled towns for R&R and some “jing bao juice.”[23] He sometimes went himself.

|

Julius said that U.S. soldiers occasionally remained in a town overnight, and the Chinese people did not bother them. The Americans were generally welcome in this country, and the Nationalist Chinese (i.e., the KMT) military seems to have made certain that they were not molested during such “forays.”[24]

If Julius was not one of the first to be sent to Pengshan, then stories told by the Hump flying crews about conditions there may have reached and enticed him to experience the place himself. For one thing, fresh chicken’s eggs were said to be commonly available at the Pengshan base (unlike Camp Salua, where only powdered eggs and milk were served to the troops), and also pork with cabbage.[25] Julius described free-range, black-skinned chickens in China – a detail that some of his friends in Rhode Island did not believe, though this is true. (These chickens are now available in Chinese groceries within the U.S.A.; their skin is dark blue to black.) An apparent favorite of his were the large peanuts grown in Sichuan province. Julius would smile when speaking of these, hold up his thick-fingered mechanic’s hand, and say “big as the end of your finger.” And in the region near Chengdu, he also saw a special method of serving tea. The people drank from delicate porcelain cups which were topped by a small “saucer” that was lifted to sip the tea.

Members of the flying crews occasionally mentioned Chinese people and soldiers in their memoirs of the Sichuan area. Their stories can make the local people seem like faceless fauna at times, and even foolish or laughable (due to ignorance). This may reflect the U.S. flyers’ sense of (or desire for) aloofness from the Chinese, who likely seemed depressingly desperate and needy, backwards, and of course very “foreign” to them. (U.S. flyers also seemed to hang together in their small and specialized groups, and seldom mixed even with non-officers among the U.S. ground personnel; this was why, Julius said, he did not attend CBI reunions in his later years – as those events tended to be dominated by former flyers, who were not the men he personally knew in the Service.) Stories told about the Chinese by U.S. airmen often focused on incidents that struck the insulated U.S. soldiers as very strange indeed – such as the tendency of Chinese peasants to run out onto a runway as an airplane came in for a landing, supposedly to scare off “ghosts” which they thought were dogging them. U.S. observers also noted (without much compassion) that some of these peasants did not survive their runs. Other stories include how enlisted Chinese soldiers would attempt to steal supplies from the airplanes if they were left unwatched, how the U.S. flyers sometimes pulled gags on the Chinese to scare them a bit for amusement, and how an unscrupulous soldier might make a fair amount of money selling American cigarettes to the poor and bedraggled Chinese – who did not seem to have much spirit to serve in their own country’s defense.

Julius knew some of these stories and told them also – particularly the one about peasants darting out before incoming U.S. airplanes. But living as he did for many months on the ground – in the countryside and in fairly close proximity to local Chinese, who served in the U.S. military kitchens and also labored to continuously repair and maintain the long and precious, hand-made B-29 runway at the A-7 base – Julius saw and remembered many things that suggest he regarded the Chinese people in Sichuan Province with both interest and respect. When he told stories about his encounters with them, he described their behaviors as sometimes humorous, sometimes curious, but often generous. He also recalled several words which he learned while speaking with them during his half-year of service near Pengshan. After more than a half-century, his Mandarin pronunciations remained correct.[26]

One of his stories involved the local kitchen cooks and their great amusement whenever the Americans demanded “lan kai shway” (cold boiled water). The Chinese drank hot tea all the time; aside from the cultural tradition and flavor, this is probably because they rightly believed it is healthier to consume hot rather than cold beverages (the boiling rendered their water much safer to consume). But the idea of using precious fuel to boil drinking water and then to purposefully allow it to become cold again (as the U.S. soldiers instructed them to do) struck the Chinese cooks as very peculiar. Another story involved mysterious black patches that the locals sometimes wore on their foreheads. Julius said he asked them about these, and was told that they were a type of medicine (such dermal patches were not familiar to him at that time in the U.S.A.).[27] Once, Julius was fascinated to observe a poor peasant man repairing his broken pottery rice-bowl very carefully, using wire to secure the fragments together. The time and effort that this process consumed to save an item that many Americans would have simply discarded clearly impressed Julius. He noted that the repair on that occasion was very well made. (A mechanic himself, Julius later kept an old toaster in repair for decades – despite the efforts of his wife Adelka to throw it away on numerous occasions.)

Julius commented more than once on the extraordinary effort that the Chinese laborers put into maintaining the Pengshan B-29 runway. He has several photos of the laborers working on that project, as well as numerous pictures of the Sichuan countryside and local people in his War Album. But his interactions were not solely with non-military peasants or the military guards. One of his “old buddies” at the A-7 base was – most atypically – a highly-ranked Chinese Nationalist officer, who is featured in the War Album. His name was “Ching Lee Ting.”[28]

|

Both were friends to Julius while he was in Pengshan; we do not know what became of “CLT.”

We don’t know where Ching Lee Ting came from or much about him personally, and we are not sure if Julius knew. He likely was not from Pengshan, or even Sichuan Province. He must have learned some English, which would not have been unusual for an educated Chinese man of his time. But apart from his participation in the War (which was likely expected for one of his class), we cannot say what he thought about the situation of his country, the Americans with whom he worked, or his future plans. Likewise, our family never knew what eventually became of Ching Lee Ting – not even whether he survived the War or lived to see the subsequent Civil War, or if he later fled the country, as so many of the surviving Nationalist officers did after 1949. Julius asked me to try to find him in the 1990s, but with only a picture and an uncertain English rendering of his name, the task was daunting if not impossible – even with the assistance of my wife, a native Mandarin-speaking Chinese woman who was born and raised in Taiwan.

Julius clearly understood that the enlisted soldiers in the Nationalist army were treated very badly; he always said it was far better to be an officer in that army. Most peasants were also poor and struggling during the War, even in the far west of China. Ching Lee Ting, a tall and educated man who was from a privileged class but still could be generous when he wished, stood near the apex of the local society. He commanded both soldiers and civilians at Pengshan. His influence as a KMT officer made him valuable to the U.S. troops in this forward base with a very limited supply line; they wanted to be his friend so that they could ask him for favors. Ching Lee Ting deflected most of their attempts. But he befriended Julius. Julius speculated that this was because he did not ask Ching Lee Ting for favors, and was instead quiet and respectful. Another reason may have been Ching Lee Ting’s knowledge of a duty that Julius acquired while in Pengshan, in addition to his work in the base motor pool (more on this below). Because he liked Julius, this officer decided to offer him small gifts from time to time, which Julius greatly appreciated. This unsolicited friendship further raised his own popularity among the U.S. soldiers as well. But Julius was mindful of what he accepted from Ching Lee Ting, because he knew how things worked in China then – for every small gift that he obtained, a local Chinese person was obliged to make a sacrifice.

The reason Julius was so interested in this man was that, despite the differences in their culture, rank, and nations – not to mention the problems that Ching Lee Ting must have had on his mind, he still took the time to be kind to Julius when this now 21 year-old soldier was half-way around the world from his own home, helping the Chinese to save their country from what would otherwise have been certain subjugation and perhaps even greater misery under the Japanese. Ching Lee Ting’s small gifts may have been a form of ‘thank you’ presents for his efforts – and they were modest, but long remembered. We know mainly of two examples – an occasional chicken for the pot, which would have helped especially in battling the cold of the Sichuan nights and winter (Ching Lee Ting also explained to Julius that dog meat was good for fighting off the cold – “Better than chicken, better than duck,” as he said); and Ching Lee Ting’s accompaniment when Julius went to local shops to purchase souvenirs. The merchants haggled with most people for their wares, but when Ching Lee Ting was there, he merely snapped his fingers meaningfully and the deal was completed. The desired item – whatever it was – became a free gift for the officer’s friend, and no complaints were raised. Julius may have obtained his opium pipe this way.

One item that Julius acquired may or may not have been obtained with Ching Lee Ting’s assistance; but this garment carried a special memory for Julius for two other reasons. At some point in mid 1944 (we do not know precisely when this occurred), Julius went to a Chinese shop with another U.S. soldier and close friend – a tall “Texan” man (whose name, unfortunately, we do not know) to purchase silk capes for their newborn children. Bonnie had been born while Julius was traveling to India on the SS Volendam (on April 14, 1944), and the “Texan” had learned of the birth of his child as well (but we do not know if his newborn was a boy or a girl). Two silk baby-sized capes were duly purchased, one for each baby. My mother still has hers. She said of it, “The cape ties at the neck and then is just a loose wrap around padded cape, blue inside, green silk outside with large orange embroidered birds and flowers on the back outside. Again, dad said they both bought one for their babies, and the other man was killed the next day or two after.” We have no details about how the “Texan” died, but Julius said that when he was informed and went to view the body of this friend, he was only able to identify him from the boots that the man always wore.[29] Whenever Julius would speak of this tragedy, he typically broke down into tears.

In addition to working in the motor pool at camp A-7, Julius had another duty during the Fall of 1944; he became an assistant to the Chaplain, Captain Jesse Leroy “Lee” Coburn, for the purpose of collecting the bodies of U.S. flyers who crashed in the area of Pengshan. From what we can tell from the materials in both Julius’s and Captain Coburn’s War collections, their range appears to have extended from Chengdu in the north to the Leshan/Emeishan region in the south of Sichuan Province. This is about a two-hour distance by modern highway, but in 1944 the time needed to cross this Sichuan area was much longer. No major highway existed then, the roads were dirt (or mud) and typically poor for motor vehicles, and many obstacles might impede their journeys – including rivers that had to be crossed by Chinese ferries. Some of the sites which they had to visit were remote, and there was always the chance that “bandits” or Japanese planes might cause further problems. The expeditions could take several days, and it seems that sometimes there were only the two of them (Julius was the driver); though at least once, there was also a third man – Lt. Warren “Deacon” Dailey (that expedition took place in early October 1944).[30]

Julius was selected for this duty because he was a motor pool mechanic. Thus, he could presumably fix their military truck if it broke down in the countryside. When I once asked him whether he was ever bothered by the task of collecting the bodies of crash-victims (he said the bodies were often in very poor condition), he replied that this was better than being a frontline infantryman. Of course, it was also more dangerous than merely being a motor pool mechanic in a forward B-29 base in western China in 1944. From his many reminiscences that derived from this particular time, I always had the impression that Julius enjoyed this duty – in fact, upon his return to the U.S.A. after the War, he wished to become a mortician (but gave this up when Adelka rejected the idea). His reasons for attaching strong feelings to this occupation were not morbid. To the contrary – his most-related stories about his time in the military revolved around these few months in China probably because of the combination of real adventure, exotic experiences, friendship, satisfaction (from doing something that was very meaningful to every soldier and to their families), and respect that he received for his participation.

Here, a short portion of a personal letter written by Chaplain Coburn about their expedition to collect the bodies of the Winkler crew in early October will highlight and mirror several memories that Julius orally related to us. I offer these excerpts exactly as the letter was written:[31]

| Word came in that “Wink’s body had been found in the mountains and I was delegated to go after it. So, at dawn, Cpl Edwards [Julius] and I loaded up a truck with blankets and rations, picked up my pal “Deacon” [Lt. Dailey], inspected our guns and started out. We crossed rivers by fording them, crossed on flatboats, drove along road built for rickshaws and thru ancient walled cities. Finally we arrive in a town at the foot of the mountains. We called on the magistrate --- he is an absolute master of about 200,000 people --- a real big shot! Hastily I recalled the language of Pearl Buck’s Good Earth”, and began negotiations in the floweriest language ever interpreted. He invited us in to tea, and with the tea he served cakes. […] |

Captain Coburn goes on to describe a full dinner that the magistrate served to them (in his lively and humorous manner – which I have edited in part, but highly encourage interested readers to seek out and enjoy, along with the rest Capt. Coburn’s collection at NEAM). Here is the final part of the journey:

| Then he [the magistrate] gave us body guards. Yes, sir! He assigned four men in uniforms to guard us --- and they were our shadows from then on. Twas quite amusing. They ate our rations, slept outside our door, ordered people out of our way, and even offered to get us some women. That, we refused, for it seemed to us that China was already over-populated. Finally, after several days, we got around to discussing the body -- and found that they had brought “Wink” down off the mountain and put him in a Buddhist Temple. I went out and identified him.. It wasn’t pleasant! He had been dead twenty one days---and we had been close friends. The Chinese asked for the privilege of paying honor to the body--- so they burned incense before it, and when we brought it out of the Temple, we found some Chinese army units paraded there as a tribute to the brave American flyer. “Wink” would have loved it! […] “Wink’s” last ride was uneventful, except that all the ferry-men insisted on burning symbolical paper money before they would let us cross on their boats. The idea was that Wink could use the money in heaven, I guess. [He continues on another topic.] |

|

Julius also told this story, as it had made a deep impression on him. His details were slightly different, and so I will recount them as he related his experience of this dinner with the magistrate at Emeishan. He did not discuss the specific reason for this particular excursion to us, apart from collecting the bodies of U.S. flyers; nor did he mention Lt. Dailey. But Julius recalled that this dinner contained several courses, and that everyone was expected to try all of them once – which he did. He liked some of the dishes and not others, and he was given the chopsticks that he used as a gift from the magistrate (Chaplain Coburn mentioned this as well; Julius eventually brought his chopsticks home). After dinner, everyone went to a porch outside to swish their teeth and then spit. The dinner was offered to honor their aid to China, and Julius recalled that they were very well treated.

|

|

Julius also remembered that the Chinese soldiers who were appointed to guard the truck containing the flyers’ remains usually deserted it if the Americans went out of sight for a time. The reason, he said, was their extreme fear of ghosts. Sometimes when they would travel to a crash site (several planes crashed near Pengshan during his brief time there) or drove to collect bodies for official burial, the local Chinese had placed them in a temple, as in this case. But often the locals merely pointed out the location of the crash. Julius also confided that the neat military cemeteries shown in pictures were mainly for show. Many of the soldiers they collected were only partial remains – and in these cases, the deceased were buried quickly in a single grave, as they could not be specifically identified. Though formal services were held in each case, if closed coffins were sent to the U.S.A., many times the named soldiers were not inside.

Julius spoke of the hazards of crossing the Chinese rivers on poled ferries, and of occasionally finding old coins or other personal items scattered over an area where Japanese bombs had struck Chinese tombs. They drove through the countryside in the autumn months of 1944, and visited Chengdu at least once – Capt. Coburn has several pictures in his War Album of himself, Julius, and a few other enlisted-rank U.S. soldiers (whose names are unknown to us) at Chengdu. In one picture, Julius and Capt. Coburn are happily buying some silk in a small Chinese shop. Another photo in his album was taken of them with a Baptist missionary named Mrs. Esther Slocum, on the West China Union University campus.

A story that Julius liked to tell about his “good buddy” the Chaplain took place on one of their journeys. They were driving down a road when they passed a young Chinese woman walking alone in a long dress that was slit up the side (possibly a cheongsam), revealing a significant stretch of her closest shapely leg. Julius was driving and keeping an eye on both the woman and the road, but then furtively peeked also at the Chaplain – and noticed that he too was intently watching this welcome spectacle. Possibly feeling a bit “off the hook,” Julius said something to the effect of “You shouldn’t be looking at that, Father!” And the Chaplain replied, “I also have two testicles – just like you, son.” This always caused Julius to smile.

Capt. Coburn seems to have traveled back and forth between the Camp Salua base near Kharagpur and the forward Chinese base at Pengshan several times in 1944-45. According to Marty, his father did not enjoy these trips at all. (Julius never rode on an airplane after returning home from Tinian either, until he reached his early 80s.) We don’t know the last time he was with Julius. Possibly, Julius’s long illness toward the end of his time in China, or Chaplain Coburn’s own serious illness soon after, separated them. Despite their shared experiences and Julius’s warm memories of the Chaplain, it seems Julius never attempted to contact him after the War ended. However, I was very happy to find Jesse “Lee” Coburn’s two sons in 2015, and was elated to learn that his elder son Marty possessed the Chaplain’s War Photo Album and several letters that he had written in 1944.[32] One of these describes Julius, and he is also featured in a few of Chaplain Coburn’s photos of China. I sent copies of Julius’s photos of the Chaplain to them and helped them to digitize the Chaplain’s WW2 materials for the Archive at New England Air Museum in Connecticut. Lee Coburn’s CBI Theater collection at NEAM is highly advised.

In his later years, Julius did consider revisiting the region of his old base in western China. Though he was never able to undertake that journey, as he grew older, he would sometimes say that soon he might “go to see the Big Buddha.” Before I traveled on my second visit to China (in 2011), I used to think this was simply a form of nostalgia for his Chinese experiences. I had not associated the temple photo above with his story about the magistrate (Julius is not in that photo), and the Coburn War Album was not yet known to me (Julius is featured with Chaplain Coburn, Lt. Dailey, and a Chinese officer named Lt. Lee in front of a large statue of a deity in one photo of that collection, but that is not the same statue as the one featured in Julius’s collection). Either of these statues easily could have formed a lasting image in his mind. Another thought also occurred to me only when I undertook my own China tour in 2011. After reaching Chengdu, then passing Pengshan and making a visit to Leshan (which is an hour further south by bus – Leshan is very near to Emeishan), I saw something that made me wonder. A giant rock-cut statue of the Buddha sits within a cliff-side along the river at Leshan. This 233 ft. tall statue is now famous and has been dreaming here with temples set around it since the 8th century AD.[33] Had Julius also heard about (or perhaps even seen) this particular “Big Buddha” when he was in Sichuan in 1944?

|

in a cliff-side at Leshan, Sichuan Province (photo taken by David Fletcher in Jan. 2011).

A few times, Julius may have thought he was going to see the Big Buddha while still in Pengshan. Many of his photos of the area seem peaceful and rural idyllic – country farming scenes, ducks being herded along the road, quiet fishermen by the river, and curious local people in city market streets or villages are commonly featured. However, he did speak of occasional Japanese bomber raids, usually at night. Other veterans who have written about the camp at Pengshan (A-7) confirm that such raids sometimes occurred in later 1944.[34] Julius said the Japanese usually attacked by air and in the night time, and that they located the camp by following the river which ran past it until they saw a bend. Knowing that the camp was near that bend, they released their bombs accordingly without being able to see the darkened camp.[35] Damages seem to have been minimal, and the raids were not common. But that may have been small comfort while planes were overhead. He also told us a story about an apparent attack by enemy soldiers on the ground – though when this happened, and precisely where, are unknown to us now.[36] The event was frightening enough to him that he remembered it rather vividly ever afterward. Bonnie, Julius’s second daughter Sherrie, and I have heard Julius say that the Japanese were “trying to kill them” one night in China by “climbing up the walls” of their compound; and he claimed to have seen one of them so close that an encounter with an Asian restaurant employee roughly 60 years after the War had ended triggered a nightmarish recollection of that night for Julius – such that he turned ashen and had to leave the eatery. Sherrie was with him at the time. After recovering, he claimed that the man looked exactly like the Japanese soldier he had seen up close in China. Due to the War, Julius generally disliked the Japanese on principle until the end of his life and never regretted his role in helping the U.S. Army Air Corps to send the war back to them.

Another of his stories about the air raids was more humorous. A lazy enlisted soldier at the A-7 base bragged to Julius that back home (I believe that was California for him), he was a “professional beggar.” In plying his trade as a panhandler, he strategically placed himself in locations where young men would bring their girlfriends for a date – hoping to impress them with dinner and a show. He would wait until a couple passed his way (romantically arm in arm was best) and then politely ask the man for any change that could be spared to help him out. He said the young bucks almost always forked over something, lest they look cheap in front of their girls. On a Friday or Saturday night in particular, he could always score enough to buy a hearty steak dinner. (I often think of this story when I see panhandlers today – whether in the U.S.A. or elsewhere; there are many “professional beggars” still in certain cities of Mainland China. The most talented pair I ever encountered were a mother and her six year-old boy in Beijing, Jan. 2010. They dressed as ragamuffins to fleece the “wealthy” foreign tourists on weekends in front of expensive hotels. The kid ran-blocker while the mother relentlessly implored you at high decibels to help her feed her son, and you just could not get around the leg-tangling junior pro until you handed him a few yuan.) The connection to air raids at the A-7 base was that, when a call came along to run for the foxholes, this enterprising fellow would always linger behind in the mess hall and eat the other soldiers’ desserts.

Julius’s closest veteran friend after the War was Charles (Charlie) H. Chase, from Derry, New Hampshire. From what we know, they first met in Pengshan (just as Julius seems to have first met Chaplain Coburn there), though Charlie (like Chaplain Coburn) was first sent to India, at about the same time as Julius.[37] Charlie was older, around 35-36 when he was in China and India, and seems mainly to have served as a Chaplain’s Assistant (several photographs in Julius’s War Album feature Charlie playing a small organ or leading soldier-choirs in military chapels). How, when, and why Charlie went to Pengshan are unknown to us; but he may have become a Chaplain’s Assistant then, and probably knew Chaplain Coburn as well.

Charlie was a musician. He played organ and accordion, and had an accordion with him while overseas (many of the photos of Charlie in Julius’s War Album feature the instrument). Not only did he play for the Chapel choir; he also occasionally entertained both the U.S. soldiers and local Chinese in the villages (also local Indians in Camp Salua). After the War, Charlie and his brothers jointly owned a tourist camp called Chases Grove in New Hampshire, and Charlie used to play the organ both there and in some other nearby locations. Bonnie remembers traveling to visit him as a child and dancing on his dance hall floor with Sherrie while Charlie played. Charlie also would visit Julius and the family in Rhode Island for many years after the War. On those occasions, he would sometimes stay for a couple of weeks at a time. He and Julius would go through their War Albums and remember old stories. Bonnie remembers hearing some of Julius’s experiences during those visits, when she was a teenager. Charlie had his own album of photographs, but we have not been able to discover its fate, despite contacting his surviving relatives.

Apparently a joyous fellow who was gifted with the ability to raise other people’s spirits, Charlie seemed to love children (though he never married), was known to be very neat in the military camps, and had a peculiar hobby while he was in the Service – he liked to collect rocks. The other soldiers liked him, but they also enjoyed playing tricks on him now and again, and used to poke fun at him for lugging around bags of rocks while he was deployed in Asia and in the Marianas. Bonnie also recalls that Charlie had the misfortune upon returning home to NH after the War to see his family home burning on the day he arrived back in Derry, and his baby grand piano falling through the floor of the burning house. But even that apparently did not dampen his spirit for long.

Had Charlie and Julius not met, it is doubtful that Julius would have owned so many photographs of his War experiences, and Bonnie might never have heard him tell many of his War-time stories, as Julius did not usually speak of the War to his family. Thus, without Charlie, Julius’s own experiences might have been rather different (less pleasant), and much of this memoir probably could never have been written.

Because Charlie was so important to both Julius and us (for his legacy), I have included several photos of him here; more can be found in the electronic collection of Julius’s War Album photos, located at NEAM.

|

|

|

The three photos below were taken while they were in Pengshan, China (at the A-7 air base).

|

|

Return to Kharagpur for eventual redeployment to the Marianas (early 1945)

By the end of January 1945, most of the U.S. ground troops stationed at Pengshan had been moved back to Camp Salua (B-1) near Kharagpur, India. Because of Julius’s long illness toward the end of his time in China, we are unsure about where he was at that time (it is possible that he was sent back to Kharagpur from Kunming rather than with the other Pengshan troops; this would have involved a different flight path over the Himalayas). But he was eventually stationed in Camp Salua again in early 1945, and was then reunited with Charlie Chase. Aside from the normal duty of assisting with the bombing missions on Japanese targets, the men at Kharagpur spent much of that Spring readying and then sending the B-29s and all of their equipment to newly prepared bases in the Marianas (on Tinian, Saipan, and Guam). The B-29s and their crews flew to the new location by April, and the ground troops traveled in ships by June.

Julius did not clearly distinguish for us what he did during his two separate periods in Camp Salua; and we have found little to enlighten us about his specific duties in his surviving military documents or the photos in his War Album (which are mostly undated, particularly in India – and sometimes also difficult to identify in regard to locations when in the various camps at Kharagpur, Pengshan, and on Tinian). In the absence of any specific recollections from this brief set of months, I will include a quote from the HISTORICAL REPORT FOR THE MONTH OF FEBRUARY 1945 by the unit commander of the 25th Air Service Group stationed in Camp Salua:

|

There has been a marked change in the weather within the past two weeks. The cool air

of the so-called Indian winter has changed into the very hot air of summer. The sun has

been blistering hot with in-the-shade temperatures of 100 degrees and more being very common. Everyone dreads to see the hot, torrid summer season approach and long for

a change to a more suitable climate. This country of India holds no lure for any GI.

Now that the advance detail has departed, we are all hoping that soon we will receive orders to pack up and leave. It will be a very happy day when we depart from the shores of India. All we want is just 'a faint recollection' of our stay in this country. The above statement has been confirmed thru the medium of concensus of opinions over a period of time.[38] |

Whether this attitude was representative of Julius’s mood in early 1945 is uncertain. It is possible that he simply may have felt glad to be alive after his long affliction from pneumonia while in China. However he may have felt then, Julius’s photos do indicate that he and Charlie spent at least a couple of days in Calcutta together, probably in late April/early May[39] – presumably after working on their units’ transport duties, and just before they and the remaining B-1 camp ground crews deployed to West Field, Tinian.

Many CBI soldiers and their families have shared photographs and stories reflecting troop excursions to Calcutta in 1944-45, but Julius told us only those stories about this city which are related in the pages above. Rather than linger on this period, I will include some more of his photos of India, taken either by or with Charlie Chase (and some by other photographers), and let them mainly speak for themselves.[40]

|

These were likely taken by either Charlie Chase or Julius in Calcutta or possibly Kharagpur, c. 1945.

|

|

Chase with a camp guard in Camp Salua; and with an Indian Muslim, possibly at Nakhoda Mosque or

Tipu Sultan Mosque in Calcutta, early 1945; and an Indian camp helper in Kharagpur.

|

An unidentified soldier at the Camp Salua laundry, and Indian soldiers (police?) in Calcutta, early 1945;

Below: three curios – (L) Calcutta Zoo, (C) same, or Perth, Australia, and (R) Eden Gardens, in Calcutta.

|

Some of the photos in Julius’s War Album were taken by other photographers, such as these:

|

The story behind the temple photo (this is located at Kharagpur), and probably the other photos as well,

is told in the Captions document included with Julius’s collection at New England Air Museum.

Julius seems to have acquired these as purchases or in trade, like some other Pacific & battle photos.

|

From early May to June 6/7, 1945, the remaining ground soldiers destined for deployment to the new bases in the Pacific sailed from Calcutta to Tinian in the Marianas, stopping briefly in Perth, Australia. Julius mentioned Perth in his itinerary and kept a few Australian coins from this journey, but related no details about the trip. I later discovered that they sailed on the troop ship U.S.S. General Leroy Eltinge, and were among the last of the 468th Bombardment Group to arrive at Tinian from India.[41] Though it was mid-dry season and viciously hot in Camp Salua, the autumn-early winter weather in Perth must have been most refreshing – especially after a long and crowded sea voyage in potentially dangerous waters.

Julius’s curious reaction to a certain woman’s name in his later years forever stuck in Bonnie’s mind. When once she was musing over girls’ names to potentially give a daughter, she tried out the sound of “Sheila” while Julius was listening. He immediately forbade her to ever name a daughter Sheila. This was a name used to refer to a prostitute, he said. Bonnie remembers this applying to women in China, but it seems more likely to be of Australian derivation. One wonders whether he heard it first in India or Perth. (Interestingly, today there is some disagreement about how derogatory the term is within Australia.) If that was a topic of conversation on the U.S.S. General Leroy Eltinge, Chaplain Coburn was no longer with the Marianas-bound soldiers to issue commentary. Suffering from an illness of his own (malaria coupled with exhaustion, according to his surviving son Marty), he was briefly sent home to the U.S.A. to recover. Chaplain Coburn eventually went to serve in Japan after the War ended.[42]

Charlie Chase did go to Tinian, as his appearance in many of Julius’s photos indicate. He and Julius were in different units on the island (Charlie was then in the 25th Air Service Group as Chaplain’s Assistant, and Julius was in the 794th Bombardment Squadron), and both probably had a lot of work to do once they arrived. Julius’s photos depict extensive construction and building work on Tinian, and the 25th Air Service Group’s records from that summer (they were the unit responsible for camp maintenance for the 468th Bombardment Group at West Field) discuss the unfinished condition of the camp at West Field in early June. Other photos in Julius’s album are of a Worship Center that was built for the soldiers (named the “Chapel in the Pines,” where Charlie seems to have played the organ during the services), numerous “sights” on the island – especially ruins from the former Japanese occupation[43] and the U.S. military cemetery there, and many tents and Quonset huts to house the troops. Numerous photos also feature the B-29s on Tinian and their interesting “nose art.”