THE ROAD THAT COULDN’T BE BUILT

THE ROAD THAT COULDN’T BE BUILT

|

|

That was the day General Pick arrived in Ledo, India, to take command of what was probably the most bogged down road building project in the history of man. Fifteen months later, this project, which his men call "Pick's Pike," was hailed around the world as one of the greatest military engineering achievements of World War II. When General Pick arrived on the scene, it looked as if the British engineers were right when they branded the project "impossible." Our own U.S. Army Engineers had taken up the task at "Mile 0.00," just outside of Ledo, where the British had given it up 10 months before. During those ten months, our engineers had pushed the road only 42 miles through the rain-soaked jungles of the Naga Hills and over the Pangsau Pass into the Patkai Mountains of Burma. |

|

|

|

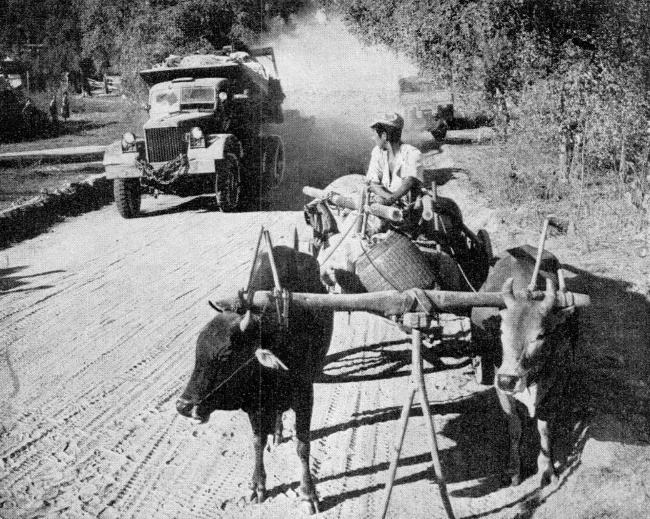

At this rate it would have taken about nine years to build the 478-mile Ledo Road through the mountains and down the Hukawng Valley to a juncture with the old Burma Road on the China border. The Japs had cut the Burma Road, the only Allied land route to China, a few months after Pearl Harbor.

The first detachment of American engineers had at their disposal only a few bulldozers, some dilapidated British trucks, a few Chinese mule pack trains, and an assortment of untrained native laborers. The road had advanced about 39 miles when the torrential rains of the 1943 monsoon season turned the new highway into a sea of mud. Fuel for the lead bulldozer had to be carried forward by coolies. Rivers rose 45 feet in a few days, washing out embankments. Bulldozers and trucks skidded over steep cliffs.

The U.S. Engineers, who slept in water-logged tents or bamboo lean-tos, were soaked to the skin all of the time. The thick, matted jungle seemed alive with purple leeches whose bites festered. The discouraged crews received reports from natives that Jap patrols had been seen only 35 miles ahead. This was March, 1943. A large contingent of Japs actually advanced within 79 miles of Ledo, but later withdrew to their supply base near Shingbwiyang.

When floods disrupted the coolie supply line, gasoline and other supplies were dropped to advance units by parachute. At "Mile 42.5," building was virtually at a standstill, and when General Pick arrived crews were working only one eight-hour shift. Ahead lay more jungle, never before crossed by a white man, precipitous mountain passes, scores of flooded rivers, and thousands of Jap snipers.

Although General Joseph W. Stilwell had informed Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek that the U.S. Army would build the lifeline into China, it looked as if the doubters were right. These doubters included many noted engineers who had announced flatly that the Ledo Road could never be built. They only had to point to any one of a dozen obstacles to prove they were right.

|

|

First, the Japs controlled most of the terrain along the proposed route which led through Shingbwiyang, Myitkyina and Bhamo. There were no detailed maps of the region and no soil charts - a vital factor in road construction. During a single monsoon season in Burma, 175 inches of rain have been known to fall, sending streams on rampages and flooding entire valleys. Other obstacles included an almost impassable 270-mile stretch of jungles and mountains, tropical diseases, a supply line that extended back 12,000 miles to the U.S., and a native labor problem that was complicated with religious and inter-tribal feuds.

"I hear they call this the road that can't be built," said General Pick at his first staff meeting in Ledo. "I've been told that all the way from the States. Too much mud, too much rain, too much disease. From now on we're forgetting this defeatist spirit. The Ledo Road is going to be built, mud and rain and disease be damned!"

From that moment things began to boom in the jungles of Burma. Headquarters were moved immediately to the most advanced point on the road and crews began working night and day. There were no flood lights for the night workers, so buckets of burning diesel oil had to serve as flares. Looking down from the heights at night they created an effect that would have delighted any Hollywood director.

|

|

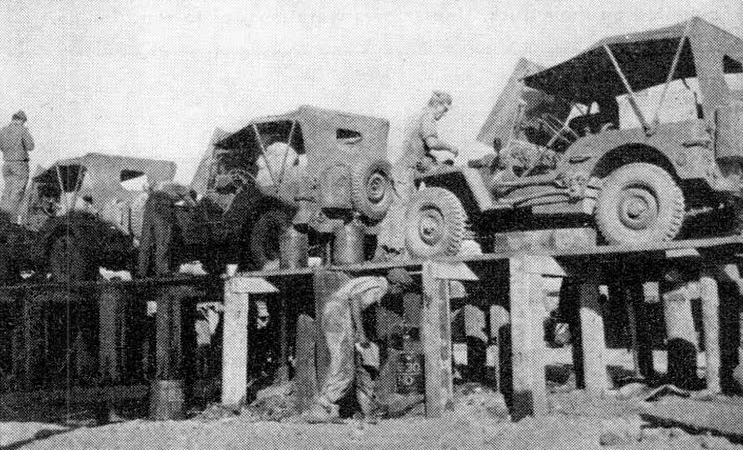

Every sanitary precaution was taken to protect the health of the men, and hot meals were available at all hours. There were a recreation program and movies to boost morale. The greatest morale boosters, however, were the new trucks and armored bulldozers, and the establishment of maintenance depots manned by first-class mechanics. One of these shops had 200 mechanics and at times there were 250 vehicles waiting to be repaired.

|

General Stilwell visited the camp a few weeks after General Pick's arrival. The Japs were 54 miles ahead, just beyond Shingbwiyang.

"Can you build us a jeep road to Shingbwiyang by January 1?" General Stilwell asked.

The date was November 3, 1943.

"No," replied General Pick, "but we will build you a military highway and have it done by that day."

If General Stilwell looked dubious, he had good reason. Before him stood a bulldozer stalled in mud up to the stacks. Between the road head and Shingbwiyang was some of the roughest terrain in the world.

Fifty-seven days later, on the morning of December 27, the lead bulldozer pushed into the edge of Shingbwiyang - four days ahead of schedule. Behind it was a convoy of 55 trucks carrying Chinese troops along the new road that climbed, dipped and zig-zagged through the mountains.

This was the opening wedge that was to drive the Japs out of North Burma, and it was to be a combined operation between road-building engineers and Chinese-American combat troops. Neither could have advanced without the other. In many places combat engineers with mine detectors had to go ahead of the bulldozers. Jap strafing planes and snipers were a constant menace, but the troops and road crews maintained a steady advance.

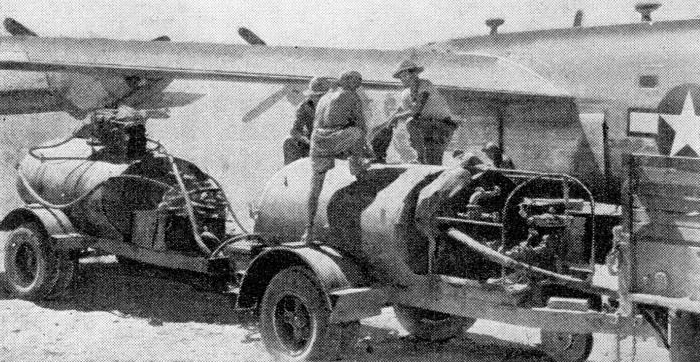

General Pick's men had to build not only the main Ledo trace, but dozens of combat roads leading off into the jungle to clean out pockets of Japs. They cut roads to battlefields all the way from Ningam Sakan to Shadazup and Warazup. They built air strips and paved the way for Brigadier General Frank Merrill's famed Marauders. One officer remarked that the tombstones of the men who gave their lives formed the milestones of the Ledo Road.

When the 1944 monsoon struck, the road had advanced to Warazup, which is about 190 miles from Ledo. While the road engineers fought the weather during the summer months to keep the highway open, the combat troops pushed the Japs out of North Burma. The fiercest battle was the 74-day siege of Myitkyina, the Jap stronghold on the Irrawaddy River. Two battalions of Ledo Road combat engineers were flown into Myitkyina to help the infantry.

Meanwhile, General Pick had been gathering a vast backlog of equipment at Warazup for the final push to Wanting on the China order. During the monsoon, a vital section of the road in the Hukawng Valley was u=inundated. For a time it seemed to be the final "impossible" obstacle.

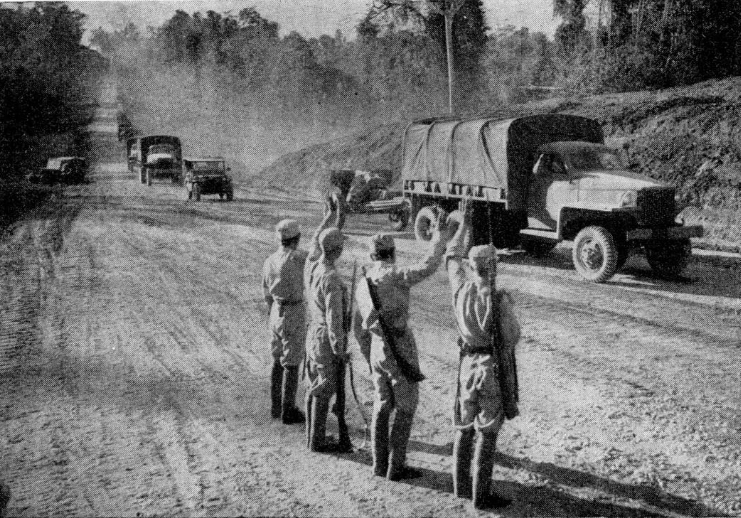

But, by this time, General Pick and his staff were used to riding roughshod over "impossible" barriers. Two GI lumber mills were quickly set up in the valley. In 30 days these mills turned out 2,400 pilings and more than a million board feet of lumber to build a causeway over the flooded area so that supplies could keep rolling.

With the end of the monsoon in October, the road was pushed along at a fast pace until another "impossible" obstacle was encountered. A huge floating bridge had to be anchored across the Irrawaddy near Myitkyina. The method by which this bridge was anchored was so successful and so ingenious that it is regarded as a military secret. This bridge is one of 165 main bridges on the Ledo Road, which crosses 10 major rivers and 155 secondary streams.

|

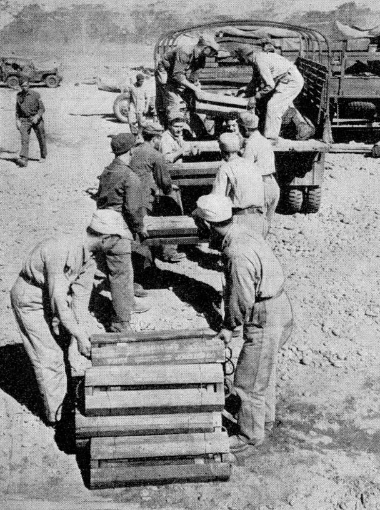

After the fall of Bhamo last December, the road builders moved on toward the China border, and in January junction was made with the Burma Road at "Mile 478" in Wanting. Under the command of General Pick, some 436 miles of the road were constructed in a 15-month period. It was officially declared open January 22, 1945.

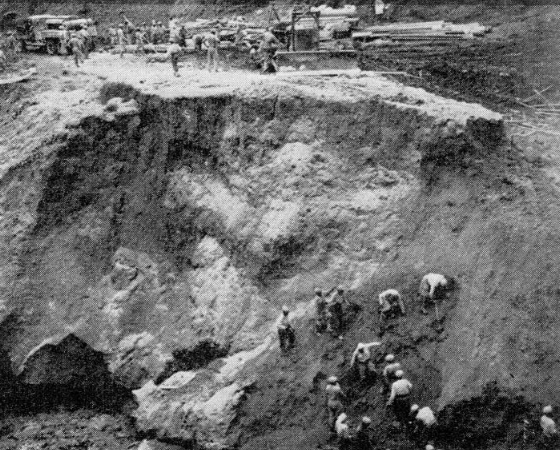

For each mile of mountain road constructed, 100,000 cubic yards of dirt had to be moved. The total amount of earth moved for the entire project was about 13,500,000 cubic yards - enough to form a dirt wall three feet wide and 10 feet high from New York to San Francisco. The culvert pipe used in the road's drainage system averaged 1,200 feet a mile, and if placed end to end the pipe would extend 105 miles.

As the Ledo Road was being built, a four inch oil pipe line was extended from Calcutta up across northeastern India. Thence it follows the same general course as the Ledo Road to Myitkyina, then crosses the Irrawaddy River.

The highway from Ledo to Kunming, China, incorporating the Ledo and part of the Burma Road, has been named the Stilwell Road by Chiang Kai-shek. This road is 1,044 miles long.

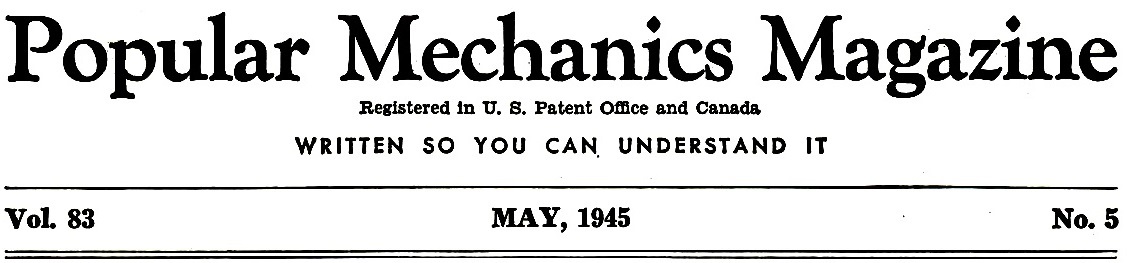

It was an historic occasion when the first convoy of nearly a hundred trucks, jeeps, ambulances and light artillery pieces set out from Ledo. There was a special Chinese guard, and General Pick rode in the lead jeep. Army engineers, Negro truck drivers, and native laborers were accorded places of honor for this epic journey. Photographers and newspaper correspondents in jeeps raced from one end of the convoy to the other. Photo planes cruised low overhead. The Engineers were tossing their hats in the air and telling the world:

"We built the road that couldn't be built!"

|

FOR PRIVATE NON-COMMERCIAL EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY

Visitors

TOP OF PAGE ABOUT THIS PAGE SEND COMMENTS

SEE THE ORIGINAL ARTICLE ON GOOGLE BOOKS

REMEMBERING THE FORGOTTEN THEATER OF WORLD WAR II